I read with great interest Richard Horton’s comment, “Offline: Why has global health forgotten cancer?” ASCP applauds his bringing light to this issue and his strong call to action for both the global health community and governments to take up the challenge of dealing with cancer. There is no doubt that the world needs a “Global Fund for Cancer” or the “President’s Emergency Plan for Cancer.” There is no question on what those funds could be spent—

prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer has been well worked out in high-income countries (HIC). There is definitely a question of how best to spend those funds, what is the most effective approach in a given population, and what special circumstances exist in a population that must be considered. We thank him for shouting about this and being so direct and for using the Lancet as a platform for this important message.

We would like to clarify, however, that Richard is certainly not the first person to shout this call (and hopefully he will not be the last!). Please review the 17 references below; one of the earliest was authored by pathologists and appeared in Lancet in 2012. In addition, the three most recent were from a Lancet Series. When I was in Malawi working in a diagnostic laboratory in 2000, more than 75% of what I saw was cancer. Although, at the time, a lot of cases found their etiology in untreated HIV. My senior colleagues told me I was wasting my time because there was “no way to treat cancer in Africa.” As I continued to visit Malawi over the next 15 years, the percentage of cases that were cancers increased. The HIV-related cancers decreased. Lung cancer never crossed the scope because there were no resources to biopsy or resect patients; yet, lung cancer was a leading cause of death in cancer registries. Today, the limited oncologists in Blantyre are overwhelmed by breast cancer cases. A similar story is found in Butaro, Rwanda and Mirebalais, Haiti.

But in all three places, patients can access a diagnosis because pathology services have been installed, bolstered, or maintained through commitments of NGOs, academic institutions, and governments. More importantly, they have access to treatment because oncologists and oncology nurses have joined the fight against cancer in global health in these units. There are many organizations in the United States and around the world that focus on cancer in low- and middle-income (LMIC) countries including (but not limited to) ASCP, PIH, UICC, ACS, CHAI, BVGH, ICCP, ICCR, NIH, APECSA, ASLM, ASCO, and, yes, the WHO. Do all of these organizations need more resources to make their missions more effective? Absolutely! Do more organizations need to join the fight? Absolutely! But, even with limited resources, huge progress can be made for individuals and populations.

In his comment, Richard points out two arguments used to explain why global health has forgotten cancer. The first is that cancer is not a statistical priority in LMICs. This is actually untrue. Advances in treatment for communicable diseases, especially HIV, have “unmasked” cancer in every one of these nations with clear evidence that many are preventable, many are curable, and many require palliative care. Mortality in Africa from cancer reaches 80% compared with only 35% for all cancers in the US. We clearly have a goal to focus on in mortality reduction with measurable targets. The WHO has announced a cancer resolution at the World Health Assembly. National Cancer Control Plans have been written for most LMICs. The stage is set for any one or all LMICs to develop, build, and expand cancer centers of excellence with people in and out of those countries eager to help. What is missing is not desire or resolve. What is missing is funding. And in this challenge, we find an actual barrier for advancing cancer care. Many organizations are drunk with funding for infectious diseases. They have no experience with cancer and no capacity to tackle it. If funding were suddenly diverted from these communicable disease organizations (CDO) to NCD organizations that could deal with cancer, many CDOs would have to close their doors. And millions would suffer at the loss of infrastructure and capacity that these organizations have created. But THAT is the ultimate barrier—the assumption that we have to divert funding. We don’t need to move funding from one program to another. We must find creative ways to finance cancer for every patient everywhere around the world.

Richard second points out that global health people tout “building systems” rather than focusing on specific cancer types (e.g., breast or cervix) as an excuse to not start cancer care. However, this is not accurate because a) health systems ARE needed to treat cancer and b) it is impossible to treat a single entity cancer and maintain an ethical program. For example, focusing on breast cancer or cervical cancer “first” or “only” is highly unethical because all the tools for those cancers also allow one to partially move a non-breast/non-cervical cancer patient through the system (the main difference being the chemotherapy types used). I do not disagree with the concept of “you have to start somewhere” but, if we think back to HIV and malaria, there is a precedent for why this is a flawed approach. HIV was a single test that diagnosed a single disease but the pre-test probability was high (since very few things looked like HIV at the height of the epidemic). RDTs for malaria were a single test that diagnosed a single disease but the pre-test probability was medium (many things look like malaria that are not). But we focused on HIV diagnosis and treatment and we focused on malaria diagnosis and treatment. Now we have HIV patients who are doing great—and getting cancer. We have malaria patients that are doing great with RDTs and ACTs—but any child with a fever of another cause probably dies. If you ask anyone with an understanding of biology or epidemiology to look at the history of the HIV epidemic or malaria in the modern age, they would all predict these findings. It’s not an epiphany…it was deliberate ignorance. Building systems is hard but it IS the answer. So, I 100% disagree with Richard that treating a single cancer will have an impact beyond those few patients that benefit from that disease. Do those patients with a specific cancer deserve treatment? Of course! But so do patients with all cancers. So, the answer IS still systems.

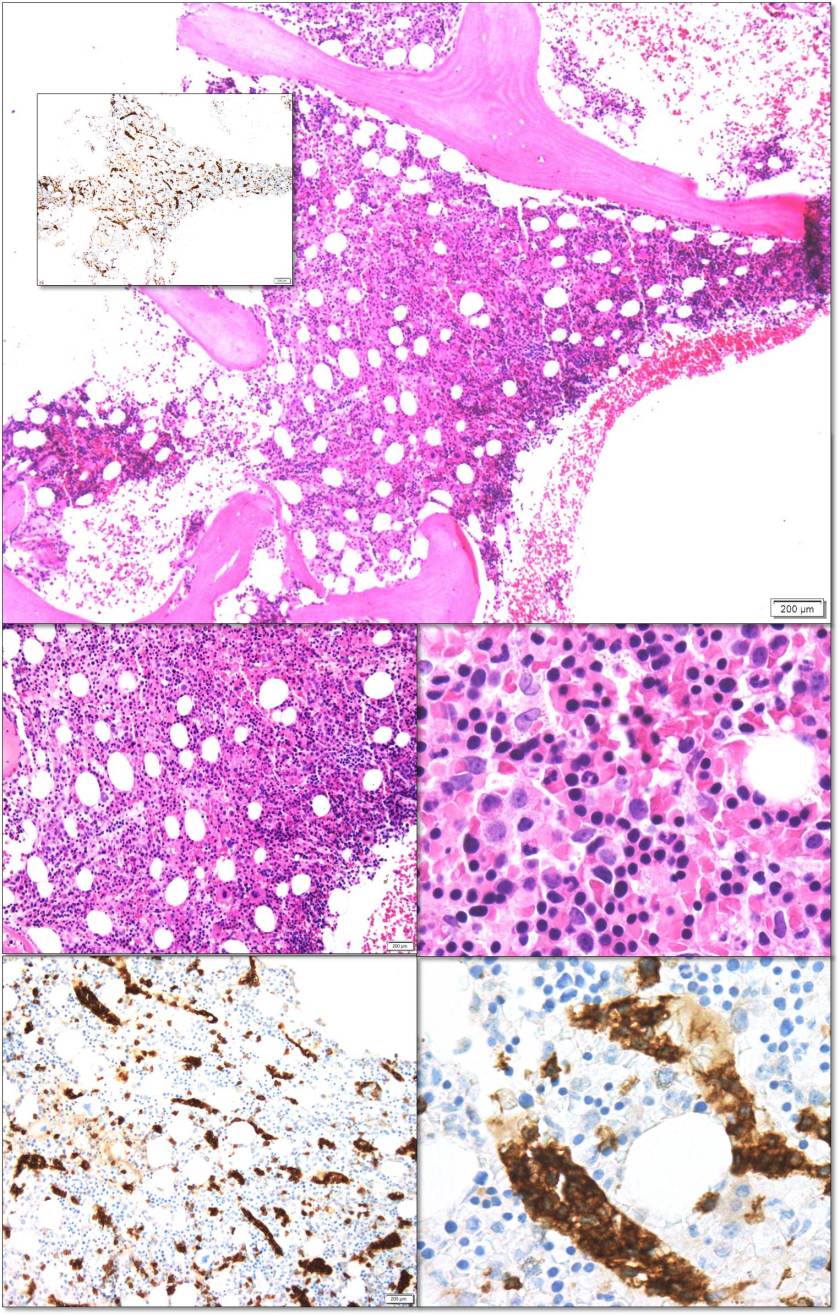

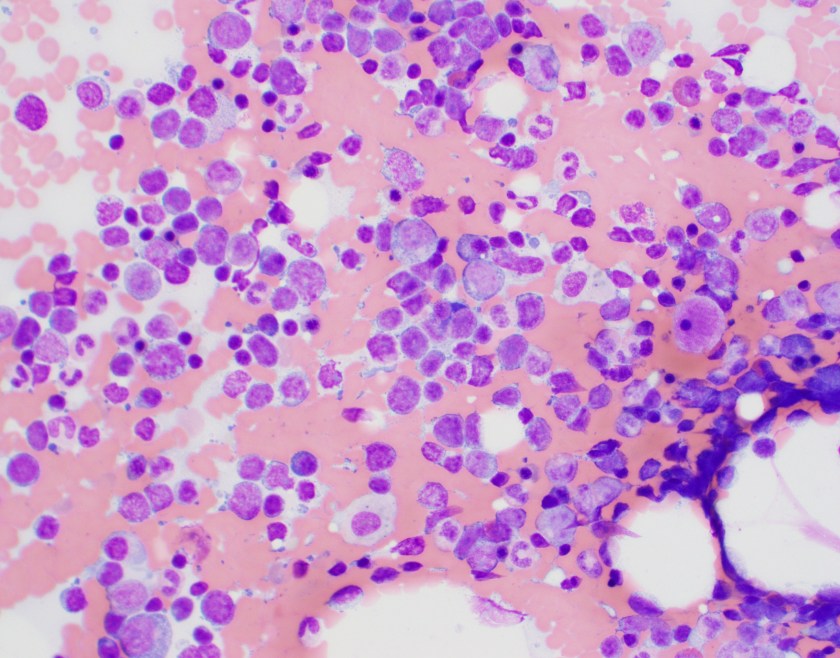

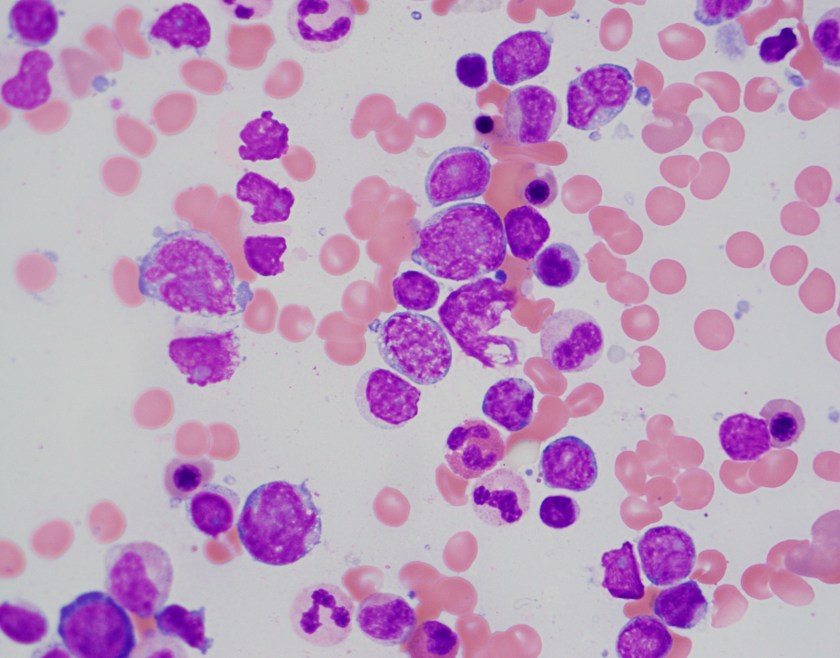

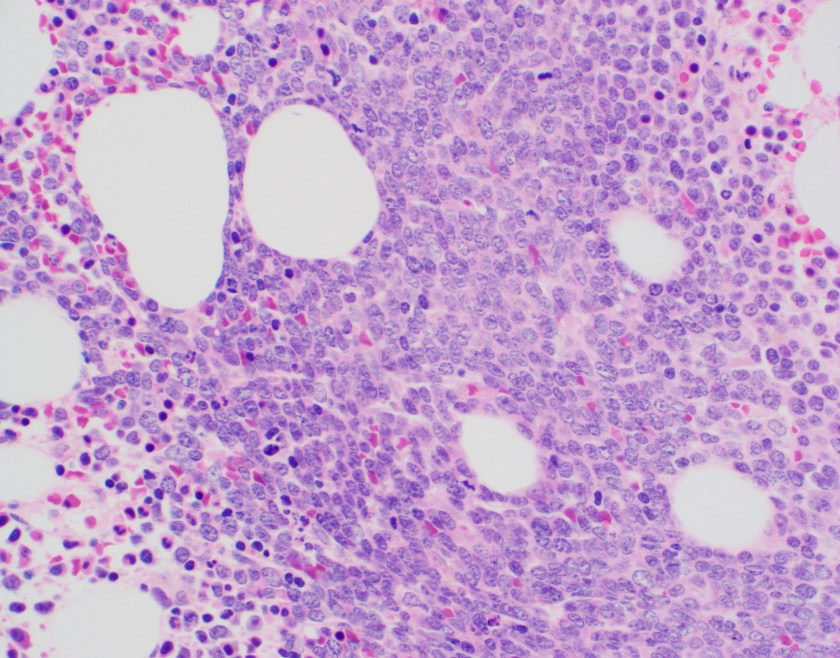

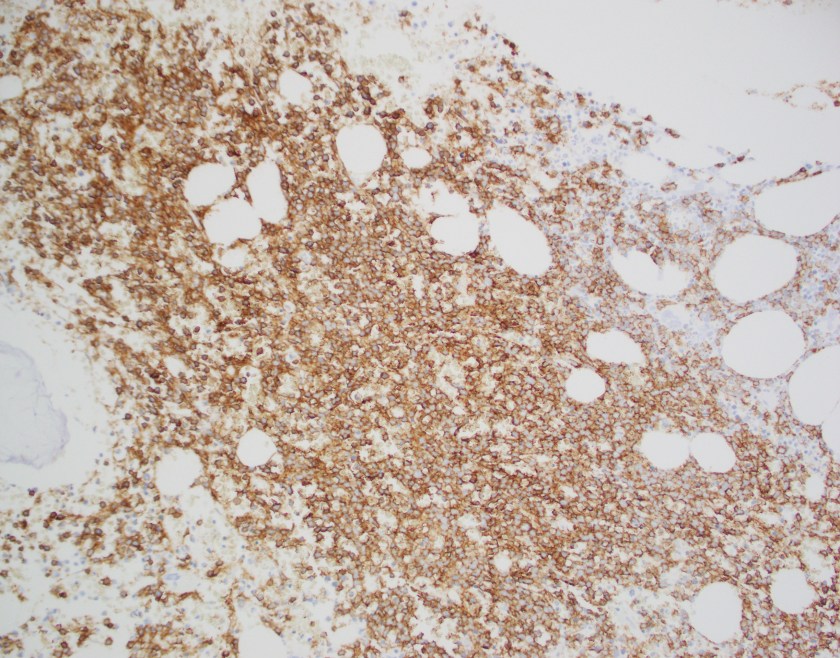

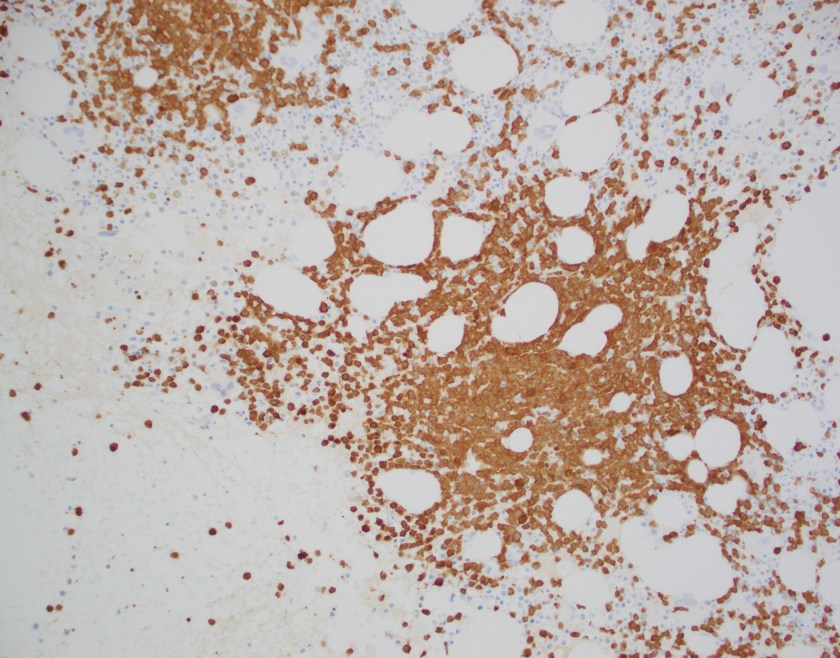

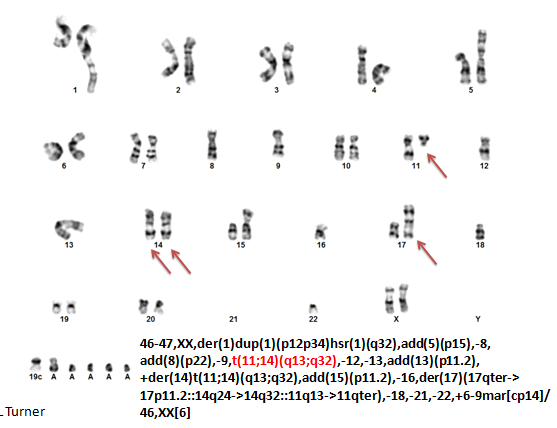

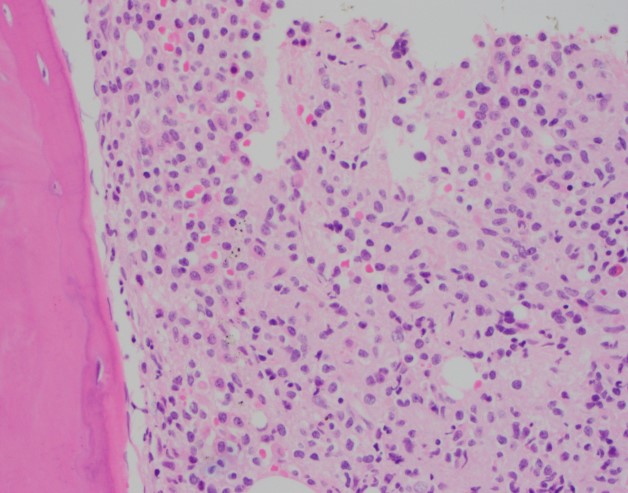

In order to treat cancer, clinicians must have a pathological diagnosis. For example, if clinicians decided that they would by assumption treat all women with Stage 4 breast cancer in Peru (with positive lymph nodes on palpation), 20% of patients would actually have tuberculosis. But a % of the patients will also have metastasis from other tumor types (such as lymphoma, benign lesions, and soft tissue tumors). If we provide chemotherapy for invasive ductal carcinoma and a pathology service to biopsy the patients to prove the diagnosis, what do we do with those that don’t actually have invasive ductal cancer? How is that ethical? Once we expand our breast tumor regiment to cover all tumors that MAY occur in the breast, now we must treat patients that have those tumors in other locations, otherwise we are in an ethical nightmare.

At the heart of this issue is the pathological diagnosis. There is no treatment without a pathological diagnosis and, once you have the ability to make a pathological diagnosis, there is not justifiable excuse for not treating patients who present with any cancer. The curse of a tissue biopsy processed for histology is that it is one test with, literally, thousands of possible results. Remember HIV and Malaria? They are each one test with one actionable result. A histology slide can present thousands of actionable results! So, no, it is not possible within an ethical construct of healthcare or within a paradigm of equity to focus on one cancer. We can deploy thousands of oncologists and nurses across LMICs with truckloads of every chemotherapy known to humankind and there would be NO IMPACT—absolutely none—unless every patient was pathologically diagnosed before treatment was begun. Surgeons could enter a country and remove every breast with a lump in it—the number of women with inappropriate surgical treatment would result in criminal charges. Pathology is the central tool for diagnosing cancer and creating an appropriate treatment plan, but it is also a single tool that can diagnose EVERY cancer so we must be able to fulfill every appropriate treatment plan.

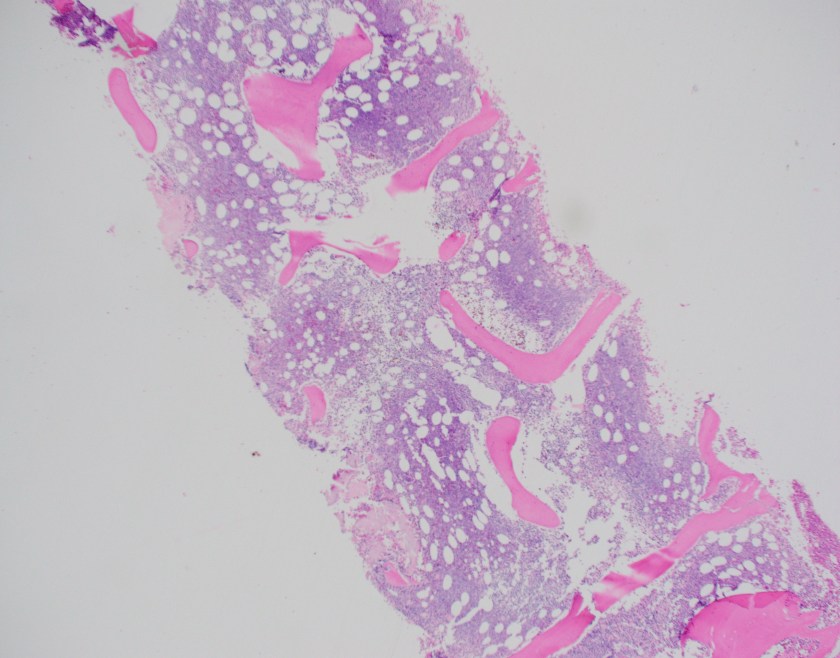

It is for this reason that PIH with assistance from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital began diagnosing and treating patients in Haiti, Lesotho, and Rwanda in 2005 with cancer. By 2011, the trickle of patients that would find their way to PIH clinics had become a flood. It was now necessary to not only build pathology laboratories in countries that could handle the volume and range of diagnoses but also import nurses and oncologists to formulate and run programs. Before the pathology laboratory was built in Butaro, Rwanda, patients may have waited for up to 6 months (if ever) to receive a result which may have been incomplete or inaccurate due to the limitation of staffing. In Butaro today, after the construction of a laboratory, training of staff, addition of immunohistochemistry, installation of telepathology, and residence of a permanent Rwandan pathologist, the turnaround time is < 72 hours. There are other success stories like this but these systems need to be replicated within country and in other countries at a rate of at least one cancer treatment center per 5 million people or less. And, as Richard rightly points out, these centers need to have resources to treat every patient.

ASCP has been in the global health arena working with PEPFAR since its inception. In 2015, ASCP launched Partners for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Africa (including Haiti) which was built on the premise that telepathology would be a key tool to diagnose patients more rapidly and accurate in LMICs. Butaro, Rwanda was the first site to receive telepathology with ASCP but there were many examples of other labs with telepathology in place prior to that; however, the bulk of them were focused on single-entity or research-based programs. The ASCP program starts with the premise that the site where telepathology is placed plans to treat all cancers that are diagnosed. Thus, ASCP requires that a system for cancer care is at least planned or in process. So, the old adage, “you have to start somewhere” is great but, for cancer, that first start must be the provision of pathology services. The ethical framework that follows will require that all cancer move into the realm of treatment.

Again, ASCP thanks Richard Horton for bringing this issue up with the Lancet audience and ASCP hopes that we, all shouting together, can move the needle much further along towards funding for cancer across the systems spectrum.

References

- Horton S, Sullivan R, Flanigan J, Fleming KA, Kuti MA, Looi LM, Pai SA, Lawler M. Delivering modern, high-quality, affordable pathology and laboratory medicine to low-income and middle-income countries: a call to action. Lancet. 2018 May 12;391(10133):1953-1964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30460-4. Epub 2018 Mar 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 29550030.

- Sayed S, Cherniak W, Lawler M, Tan SY, El Sadr W, Wolf N, Silkensen S, Brand N, Looi LM, Pai SA, Wilson ML, Milner D, Flanigan J, Fleming KA. Improving pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries: roadmap to solutions. Lancet. 2018 May 12;391(10133):1939-1952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30459-8. Epub 2018 Mar 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 29550027.

- Wilson ML, Fleming KA, Kuti MA, Looi LM, Lago N, Ru K. Access to pathology and laboratory medicine services: a crucial gap. Lancet. 2018 May 12;391(10133):1927-1938. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30458-6. Epub 2018 Mar 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 29550029.

- Sayed S, Cherniak W, Lawler M, Tan SY, El Sadr W, Wolf N, Silkensen S, Brand N, Looi LM, Pai SA, Wilson ML, Milner D, Flanigan J, Fleming KA. Improving pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries: roadmap to solutions. Lancet. 2018 May 12;391(10133):1939-1952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30459-8. Epub 2018 Mar 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 29550027.

- Milner DA Jr. Pathology: Central and Essential. Clin Lab Med. 2018 Mar;38(1):xv-xvi. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.11.001. Epub 2017 Dec 12. PubMed PMID: 29412893.

- Milner DA Jr. Global Health and Pathology. Clin Lab Med. 2018 Mar;38(1):i. doi: 10.1016/S0272-2712(17)30139-7. Epub 2018 Feb 3. PubMed PMID: 29412888.

- Orozco JD, Greenberg LA, Desai IK, Anglade F, Ruhangaza D, Johnson M, Ivers LC, Milner DA Jr, Farmer PE. Building Laboratory Capacity to Strengthen Health Systems: The Partners In Health Experience. Clin Lab Med. 2018 Mar;38(1):101-117. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.10.008. Epub 2017 Dec 28. Review. PubMed PMID: 29412874.

- Milner DA Jr, Holladay EB. Laboratories as the Core for Health Systems Building. Clin Lab Med. 2018 Mar;38(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.10.001. Epub 2017 Dec 1. Review. PubMed PMID: 29412873.

- Dayton V, Nguyen CK, Van TT, Thanh NV, To TV, Hung NP, Dung NN, Milner DA Jr. Evaluation of Opportunities to Improve Hematopathology Diagnosis for Vietnam Pathologists. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017 Nov 20;148(6):529-537. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqx108. PubMed PMID: 29140404.

- Mpunga T, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Tapela N, Nshimiyimana I, Muvugabigwi G, Pritchett N, Greenberg L, Benewe O, Shulman DS, Pepoon JR, Shulman LN, Milner DA Jr. Implementation and Validation of Telepathology Triage at Cancer Referral Center in Rural Rwanda. J Glob Oncol. 2016 Jan 20;2(2):76-82. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.002162. eCollection 2016 Apr. PubMed PMID: 28717686; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5495446.

- Sayed S, Lukande R, Fleming KA. Providing Pathology Support in Low-Income Countries. J Glob Oncol. 2015 Sep 23;1(1):3-6. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.000943. eCollection 2015 Oct. PubMed PMID: 28804765; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5551652.

- Nelson AM, Milner DA, Rebbeck TR, Iliyasu Y. Oncologic Care and Pathology Resources in Africa: Survey and Recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 1;34(1):20-6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9767. Epub 2015 Nov 17. Review. PubMed PMID: 26578619.

- Mpunga T, Tapela N, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Milner D, Nshimiyimana I, Muvugabigwi G, Moore M, Shulman DS, Pepoon JR, Shulman LN. Diagnosis of cancer in rural Rwanda: early outcomes of a phased approach to implement anatomic pathology services in resource-limited settings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Oct;142(4):541-5. doi: 10.1309/AJCPYPDES6Z8ELEY. PubMed PMID: 25239422.

- Mtonga P, Masamba L, Milner D, Shulman LN, Nyirenda R, Mwafulirwa K. Biopsy case mix and diagnostic yield at a Malawian central hospital. Malawi Med J. 2013 Sep;25(3):62-4. PubMed PMID: 24358421; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3859990.

- Berezowska S, Tomoka T, Kamiza S, Milner DA Jr, Langer R. Surgical pathology in sub-Saharan Africa–volunteering in Malawi. Virchows Arch. 2012 Apr;460(4):363-70. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1217-z. Epub 2012 Mar 10. PubMed PMID: 22407448.

- Roberts DJ, Wilson ML, Nelson AM, Adesina AM, Fleming KA, Milner D, Guarner J, Rebbeck TR, Castle P, Lucas S. The good news about cancer in developing countries–pathology answers the call. Lancet. 2012 Feb 25;379(9817):712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60306-7. PubMed PMID: 22364759.

- Carlson JW, Lyon E, Walton D, Foo WC, Sievers AC, Shulman LN, Farmer P, Nosé V, Milner DA Jr. Partners in pathology: a collaborative model to bring pathology to resource poor settings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Jan;34(1):118-23. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c17fe6. PubMed PMID: 19898229.

-Dan Milner, MD, MSc, spent 10 years at Harvard where he taught pathology, microbiology, and infectious disease. He began working in Africa in 1997 as a medical student and has built an international reputation as an expert in cerebral malaria. In his current role as Chief Medical officer of ASCP, he leads all PEPFAR activities as well as the Partners for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Africa Initiative.