Case History

The patient is a 43 year old woman who experienced chest congestion and presented to her local physicians office. A chest X-ray was ordered and demonstrated a lung abnormality. A follow-up CT scan confirmed a 1.9 cm smoothly marginated nodule in the upper lobe with no adenopathy and a normal liver and adrenal glands. The nodule was mildly hypermetabolic on PET scan. A bronchoscopy was performed, which was non-diagnostic. Two subsequent CT scans demonstrated no change in the size of the nodule. Overall, the patient feels well and denies cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss. Due to the suspicion of cancer, the patient has decided to undergo a lung lobectomy.

Diagnosis

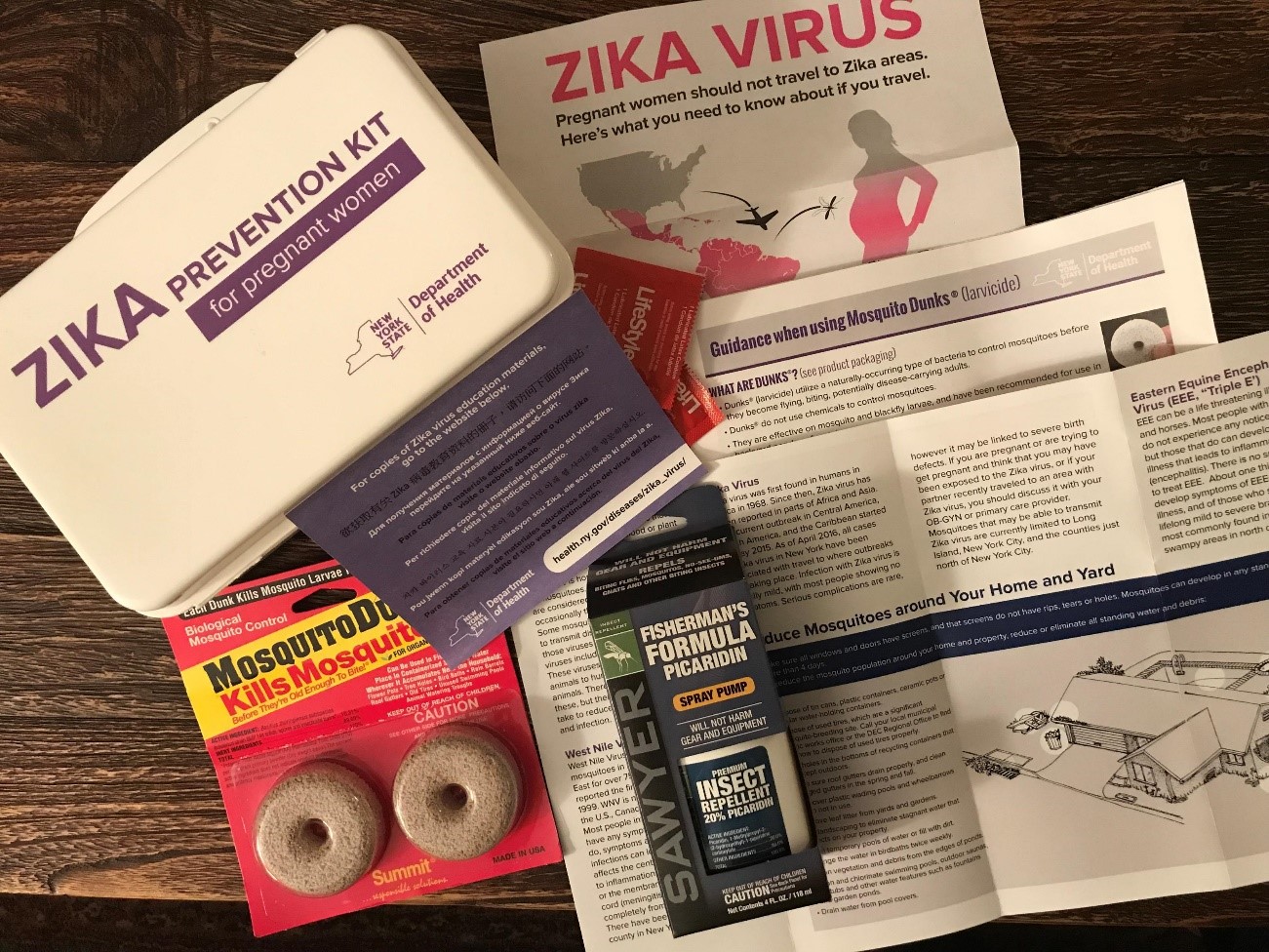

Received in the Surgical Pathology lab for intraoperative consultation is a 30.0 x 7.2 x 2.2 cm lung lobectomy specimen. There is an attached 6.2 cm staple line, which is removed and the subjacent resection margin is inked blue. The entire pleural surface is inked black. The specimen is sectioned revealing a 2.1 x 1.7 x 1.0 cm white-tan, firm, round nodule that is 0.5 cm from the blue inked resection margin and 0.2 cm from the black inked pleural surface. The remainder of the specimen is composed of red-tan, spongy, grossly unremarkable lung parenchyma without nodules or other lesions. Photographs of the specimen are taken (Figure 1). A representative section of the nodule is submitted for frozen section and read out as “diagnosis deferred”. Representative sections of the specimen are submitted as follows:

A1FS: Frozen section remnant

A2-A7: Nodule, entirely submitted

A8-A10: Grossly unremarkable lung parenchyma

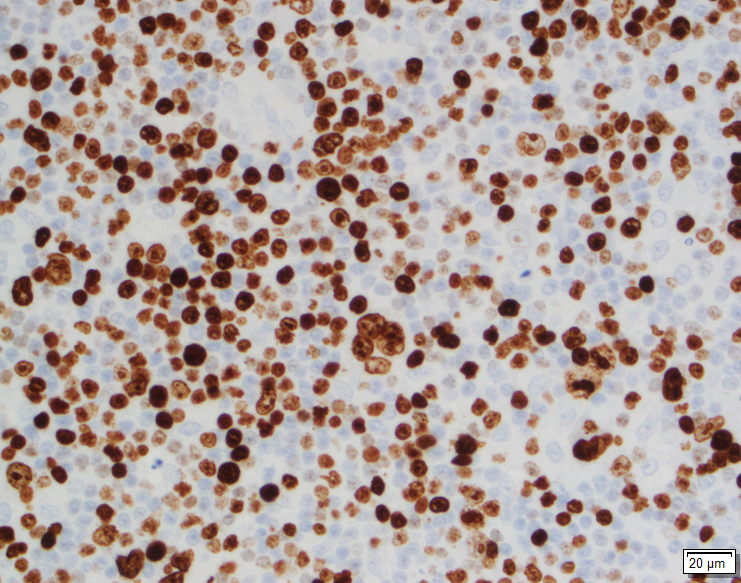

Immunohistochemical stains show the epithelial cells in the lesion to be positive for CK7, TTF-1, and surfactant proteins A and B which supports these cells to be type 2 pneumocytes (all controls are appropriate). Based on the immunohistochemical stains and routine H&E slides, the case was signed out as a sclerosing pneumocytoma

Discussion

Sclerosing pneumocytoma (SP) is a rare, benign pulmonary tumor that was first described in 1956 as a vascular tumor, but has since been found to be of primitive respiratory epithelium origin. In the past, SP has also been referred to as sclerosing hemangioma, pneumocytoma, and papillary pneumocytoma, but the 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors states that the agreed upon term for this tumor should be a sclerosing pneumocytoma. SP is commonly seen in middle aged adults, with a female to male ratio of 5:1. There is no racial bias. Patients are usually asymptomatic, with the tumor incidentally found on screening chest radiographs. If the patient was to present with any symptoms, they would usually include a cough, hemoptysis and chest pain. Radiographically, SP appears as a solitary, well-defined, homogenous nodule along the periphery of the lung.

Grossly, most SPs appear as a solitary, firm, well-circumscribed, yellow-tan mass generally arising along the periphery of the lung. The majority of these tumors appear within the lung parenchyma, but there have been cases reported of endobronchial and pleural based SP tumors. Multifocal unilateral tumors and bilateral tumors are uncommon.

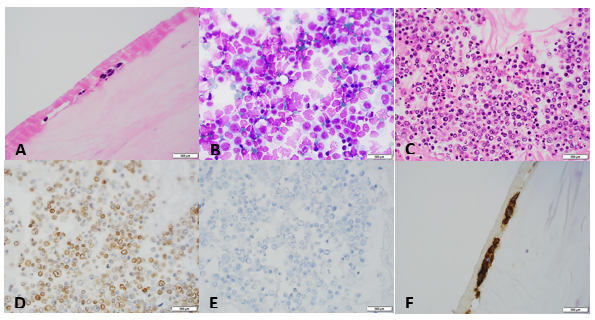

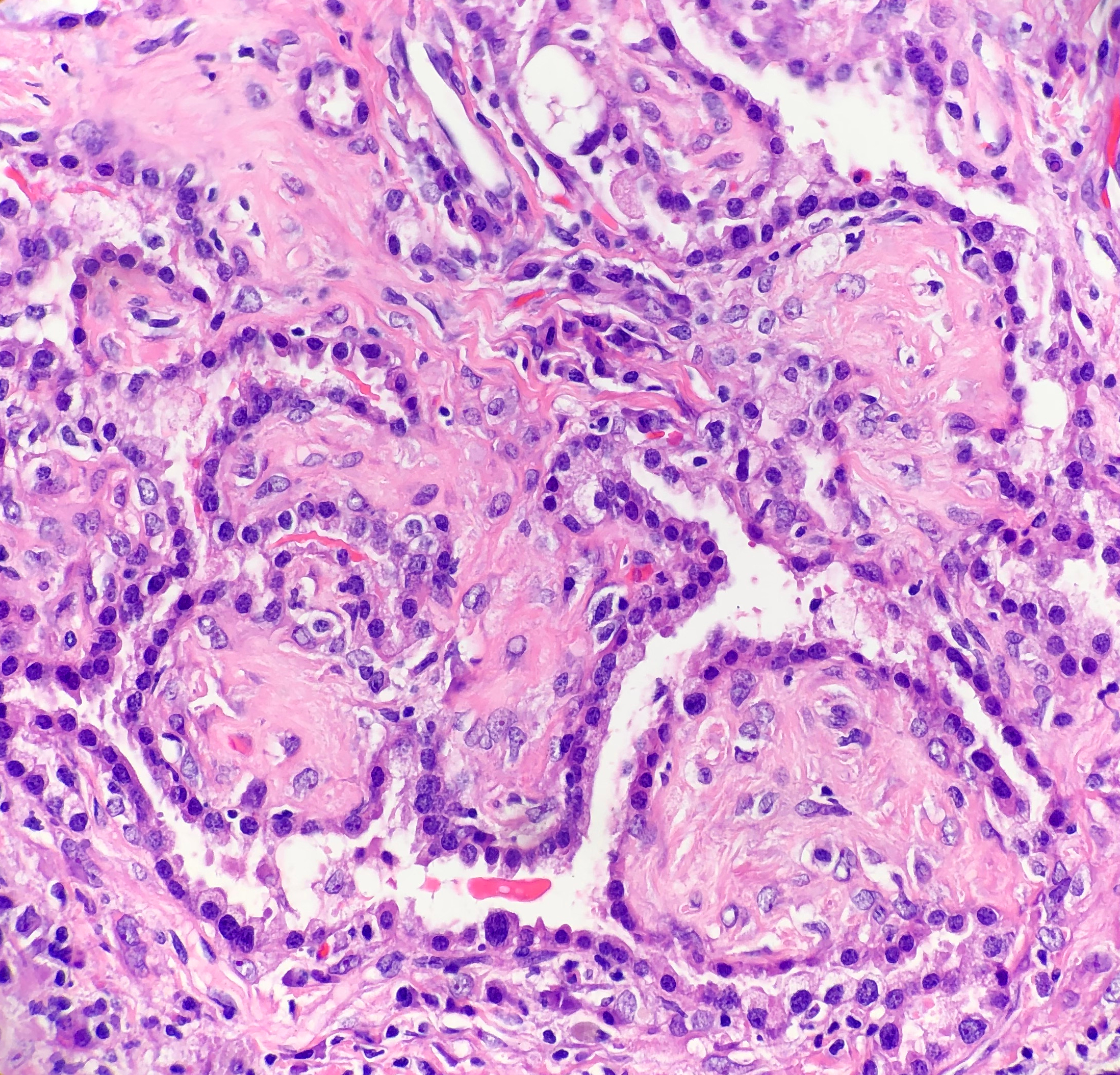

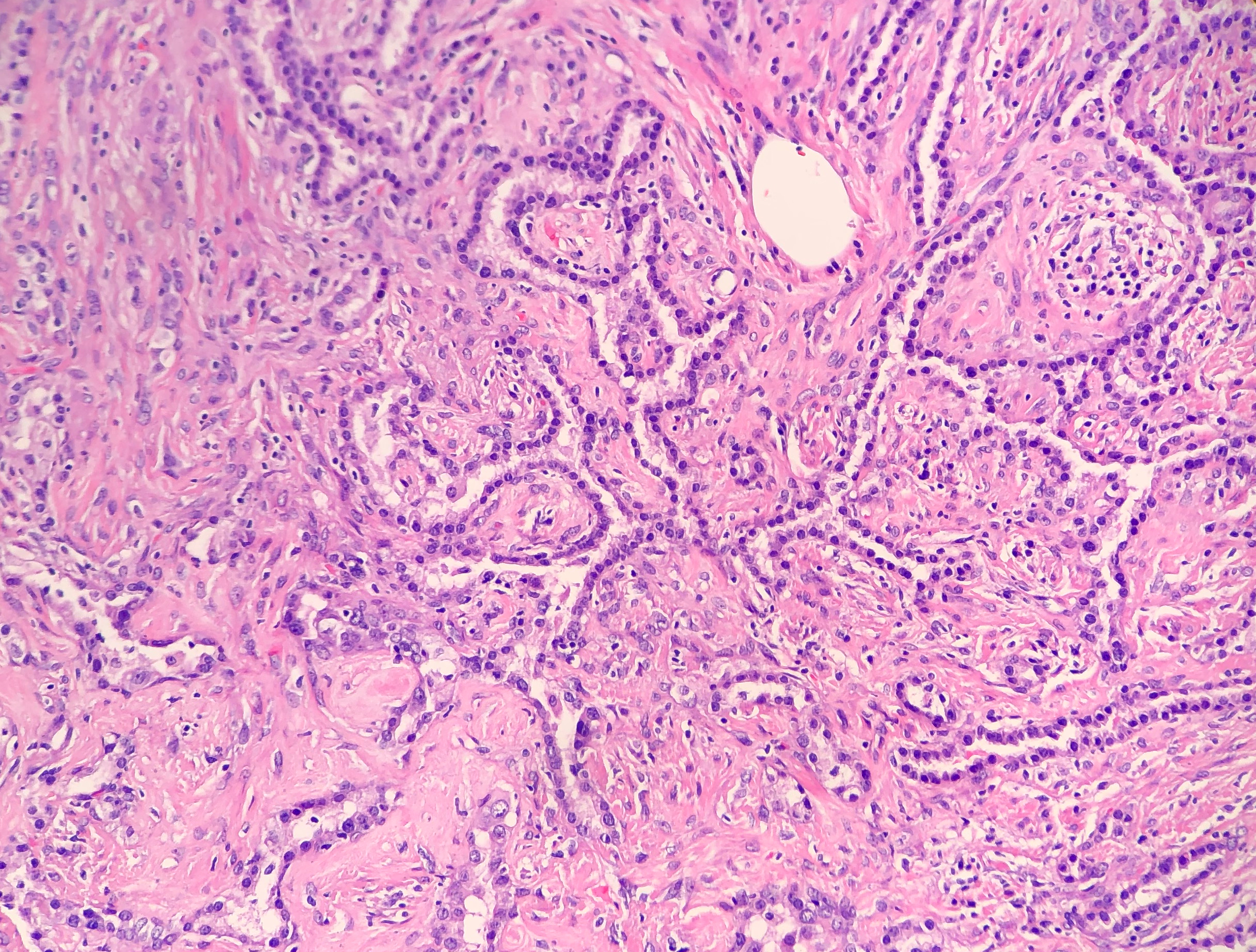

Histologically, SP consists of two epithelial cell types: surface cells and round cells. Surface cells are cuboidal, resembling type II pneumocytes, with finely stippled nuclear chromatin, indistinct nuclei, occasional nuclear grooves, and inclusions. The stromal round cells will have bland oval nuclei with coarse chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Both the surface cells and round cells will have a low mitotic rate, but can have moderate to marked nuclear atypia. Ciliated bronchial epithelium is often identified in the tumor. There are four architectural patterns identified within SP: papillary, sclerotic, solid and hemorrhagic, with over 90% of SPs displaying three of the patterns, and all of the tumors containing at least two of the patterns.

- Papillary pattern: Complex papillae composed of surface cells covering a stroma of round cells

- Sclerotic pattern: Papillae containing hyalinized collagen, either in solid areas or along the periphery of hemorrhagic areas (Figure 3)

- Solid pattern: Sheets of round cells bordered by surface cells

- Hemorrhagic pattern: Large blood filled spaces

Immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in the diagnosis of SP, with both the surface cells and round cells exhibiting expression of thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). It should be noted that TTF-1 is also used for the diagnosis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, increasing the risk of misdiagnosing SP. The surface cells will also express both pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and Napsin A, with the round cells being negative for AE1/AE3, but having a variable expression of cytokeratin 7 and the low molecular weight cytokeratin (CAM 5.2). Molecular pathology has demonstrated a frequent loss of heterozygosity at 5q, 10q and 9p, and an allelic loses at p16 in the surface and rounds cells. Although the immunohistochemical stains and molecular pathology results can be very helpful, diagnosis of a SP is still largely based on routine H&E slides showing the two epithelial cell types and four architectural patterns.

Electron microscopy will show abundant lamellar bodies similar to those in type II pneumocytes in the surface cells. Round cells will lack the lamellar bodies and instead will contain variably-sized electron-dense bodies that have been thought to represent the different stages of lamellar body maturation.

The differential diagnosis for SP includes a variety of benign and malignant neoplasms, which can be difficult to distinguish on cytology, small biopsies and intraoperative consultations. The cytologic features include moderate to high cellularity with a bloody background and foamy macrophages, occasional nuclear pleomorphism in the round cells, absent mitotic figures, and occasional necrosis with cholesterol clefts and calcifications. In the case of small biopsies, making a diagnosis of SP can be difficult if the papillary pattern is highly prevalent without one of the other three patterns present. With intraoperative consultations, the frozen section artifact can make it difficult to appreciate the two epithelial cell types or the four architectural patterns. The gross examination, as well as the radiographic findings of a well-circumscribed tumor can help point the Pathologist to favoring a benign neoplasm over a malignant one. The benign neoplasms that should be considered in the differential diagnosis include:

- Clear cell tumor, which will have clear cells with scant stroma, thin-walled vessels and a strong expression of HMB-45

- Pulmonary hamartoma, which will have a combination of cartilage, myxoid stroma, adipose tissue and trapped respiratory epithelium

- Hemangiomas, which are rare in the lung, and will lack epithelial cells and contain either a cavernous or capillary morphology

The malignant neoplasms that should be considered in the differential diagnosis include:

- Bronchioalveolar carcinoma, which can have a papillary pattern, but will not contain the two epithelial cell types and combination of the four architectural patterns

- Metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma, which is distinguished from SP by the presence of the characteristic Orphan Annie nuclei

- Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, which will contain nuclear atypia and striking vascularity

- Carcinoid, which will contain organoid and ribbon-like growth patterns

Currently, with the benign nature of SP, surgical excision is the preferred treatment choice to cure the patient. There have been cases reported of lymph node metastasis and recurrence, but neither of these appear to effect the prognosis. This just helps to highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach to this benign tumor.

References

- Hisson E, Rao R. Pneumocytoma (sclerosing hemangioma), a Potential Pitfall. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45(8):744-749

- Keylock JB, Galvin JR, Franks TJ. Sclerosing Hemangioma of the Lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(5):820-825.

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243-1260.

- Wu R. Sclerosing Pneumocytoma (Sclerosing Hemangioma). Pathology Outlines. http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungtumorsclerosingheman.html. Revised February 19, 2019. Accessed June 6, 2019.

-Cory Nash is a board certified Pathologists’ Assistant, specializing in surgical and gross pathology. He currently works as a Pathologists’ Assistant at the University of Chicago Medical Center. His job involves the macroscopic examination, dissection and tissue submission of surgical specimens, ranging from biopsies to multi-organ resections. Cory has a special interest in head and neck pathology, as well as bone and soft tissue pathology. Cory can be followed on twitter at @iplaywithorgans.