Clinical History

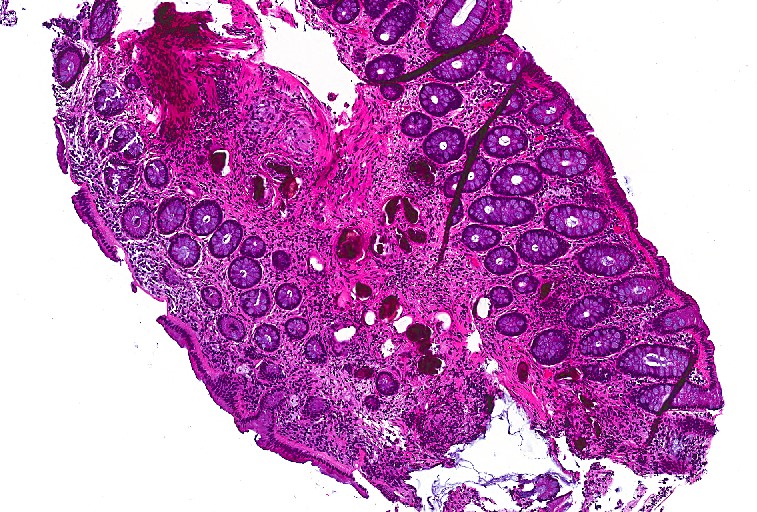

A 55 year old female presented to the gastroenterology clinic with a chief complaint of cough and headache. She reported no recent fevers, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. On further questioning she revealed she was originally from the Philippines and had a past history of a parasitic infection that was treated twice with praziquantel. She did not remember the name of the parasite but was concerned for a recurrent infection. A stool specimen for ova & parasite exam and basic laboratory work, including an IgE level, were collected and the patient was scheduled for a screening colonoscopy. Findings from the colonoscopy revealed no gross evidence of neoplastic or infectious disease; however, random rectal biopsies were obtained.

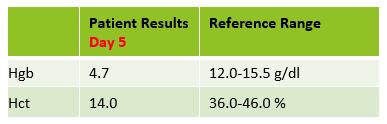

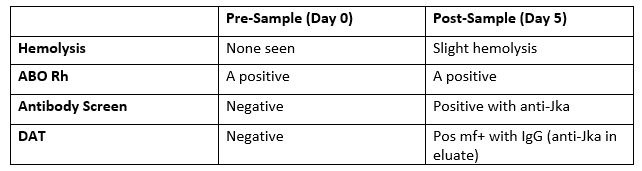

Laboratory Identification

Discussion

Schistosoma japonicum is a trematode that can infect humans through direct penetration of the skin by the cercariae when wading or swimming in infected waters in the Far East, such as China, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand. Infection can initially present as swimmer’s itch and then develop into Katyama syndrome, which includes fever, eosinophilia, muscle aches, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

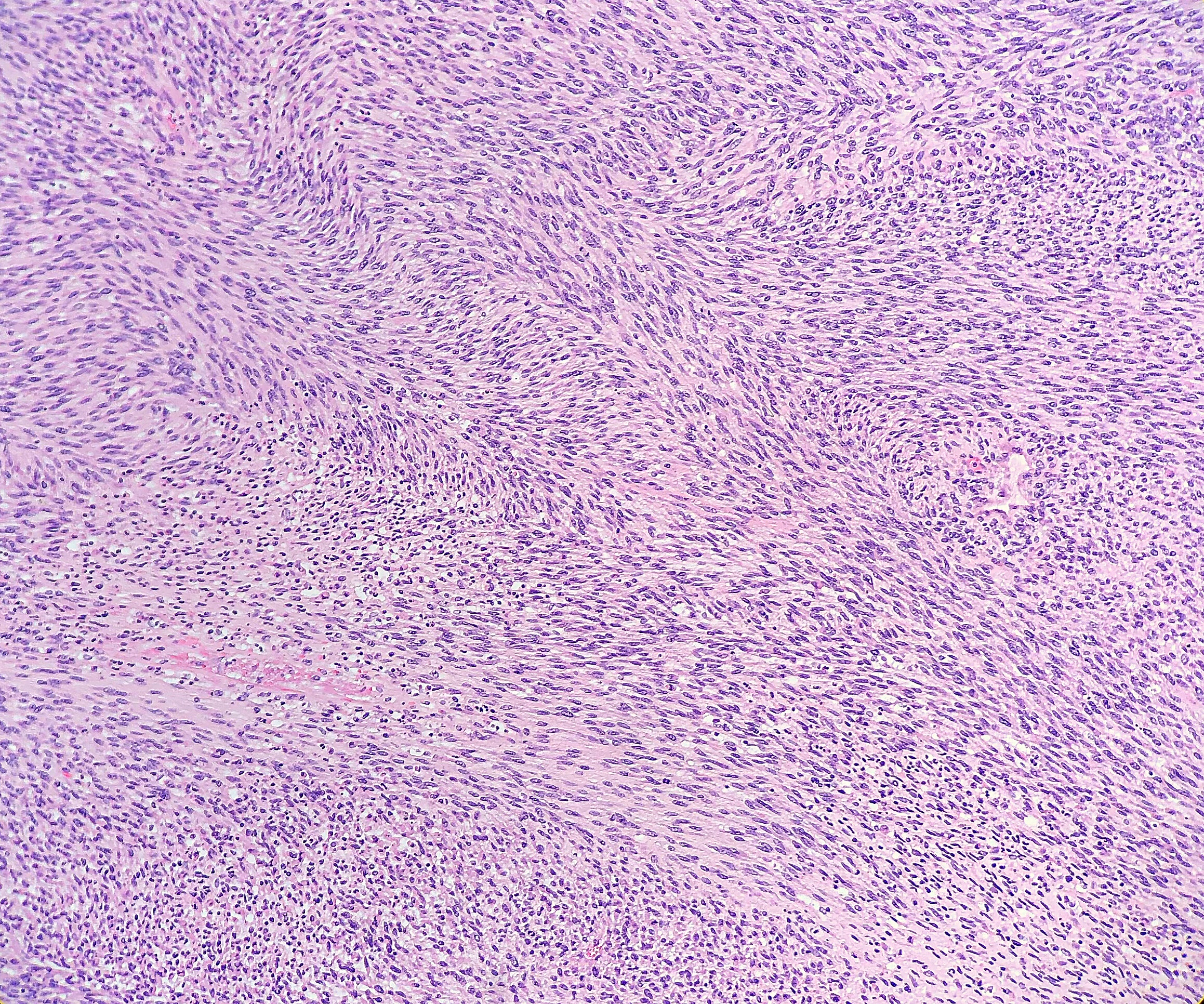

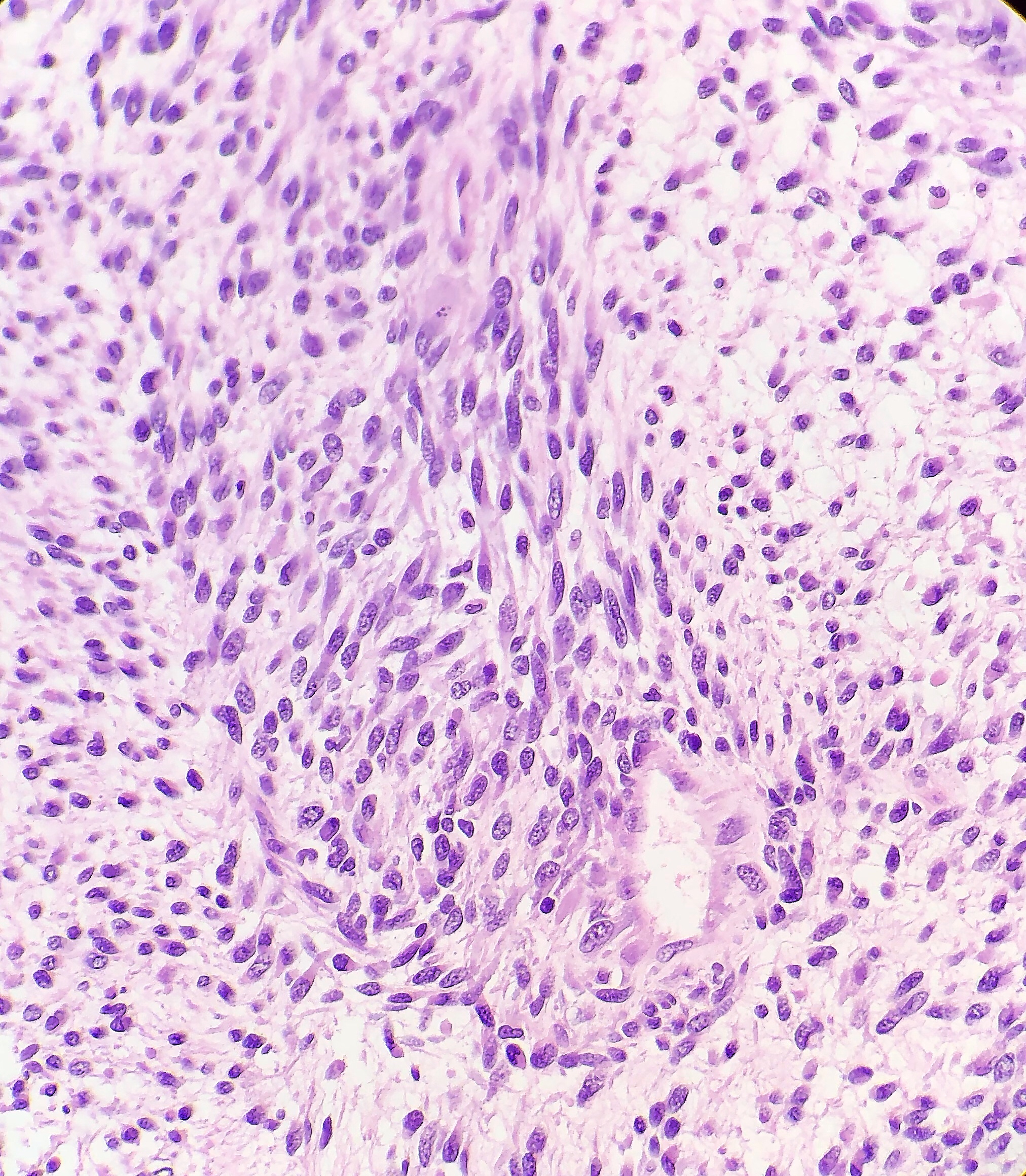

S. japonicum migrates through tissues and the adult male & female forms take up residence in the mesenteric veins that drain the small intestine. The female lays eggs which travel to the lumen of the intestines and can be shed in the stool. The host immune response to the eggs is the major cause of clinical disease which presents as inflammation & ulceration in the intestines, portal fibrosis in the liver & splenomegaly, and more rarely, lesions in the central nervous system. As with all trematodes, snails serve as the intermediate host.

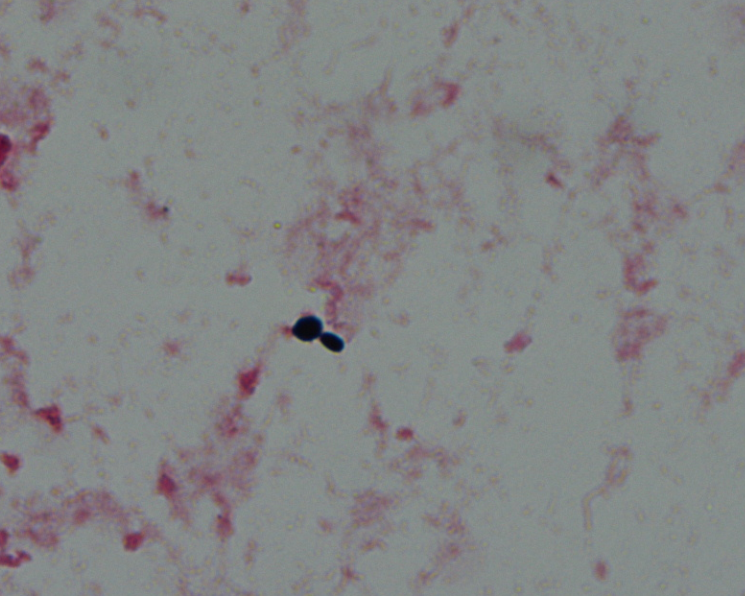

In the microbiology laboratory, diagnosis is usually made by identification of the eggs in stool specimens. The eggs of S. japonicum are ovoid in shape with a transparent shell and a small, inconspicuous spine. The eggs typically measure between 70-100 um in greatest dimension. These eggs can commonly be visualized in rectal biopsies as well. It is important to get an accurate measurement of the size of the egg and multiple sections to be able to detect the location and morphology of the spine. The eggs of S. japonicum must be distinguished from those of S. mekongi which is similar in appearance; however, the latter is found along the Mekong River in Southeast Asia and is smaller in size (50-70 um in greatest dimension). Serology is also a viable diagnostic test in those that have traveled to endemic regions, but sensitivity and specificity of the assays vary depending on how the antigen is prepared and the Schistosoma species of interest.

Treatment of choices for those infected with S. japonicum is praziquantel divided into three doses over the course of one day and it should be administered at least 6 to 8 weeks after the last exposure to contaminated freshwater. Since our patient admitted to a recent visit to the Philippines with potential exposure to infected waters, she received another course of praziquantel therapy.

-Anas Berneih, MD, is a fourth year Anatomic and Clinical Pathology chief resident at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

-Lisa Stempak, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. She is certified by the American Board of Pathology in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology as well as Medical Microbiology. She is the Director of Clinical Pathology as well as the Microbiology and Serology Laboratories. Her interests include infectious disease histology, process and quality improvement, and resident education.