Case History

A 68 year old male with no significant past medical history who enjoys long distance cycling presented to an outside emergency department with dyspnea on exertion. Laboratory values at the outside facility showed profound anemia (Hb 10 g/dL) and physical exam revealed lymph adenopathy. The patient was discharged but presented again to his primary care physician with profound dyspnea on exertion, especially after climbing one flight of stairs. Of note, his anemia had worsened with a new Hb of 7 g/dL. For evaluation of the anemia, the patient had a Coomb’s test and it was positive, overall consistent with cold agglutinin disease. For evaluation of the lymphadenopathy, a CT abdomen and chest revealed celiac, portocaval, mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy as well as mild splenomegaly. Due to these findings, the patient presented to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for further evaluation and biopsy of a retroperitoneal lymph node.

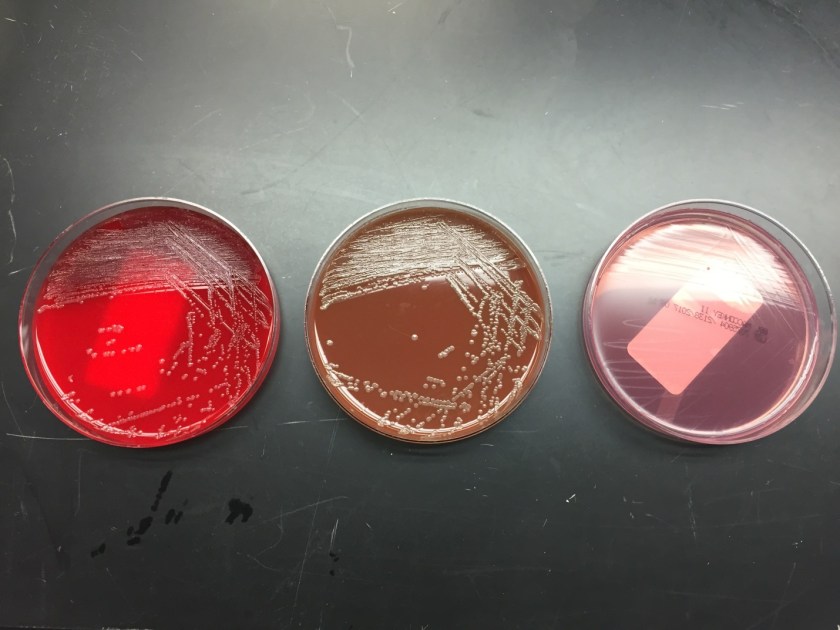

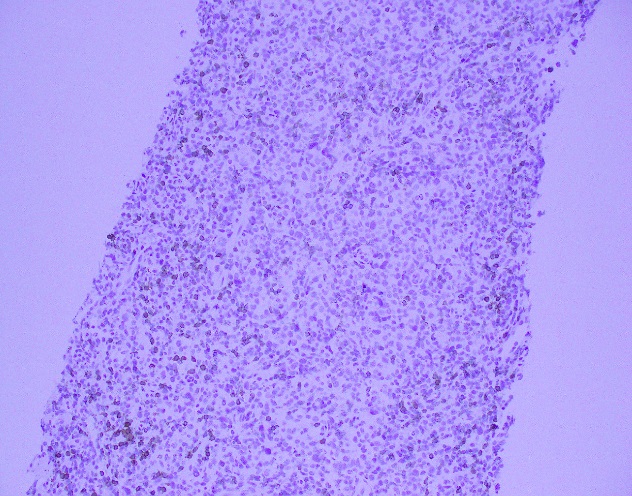

A core needle biopsy of a retroperitoneal lymph node was obtained per the recommendation of hematology/oncology.

Diagnosis

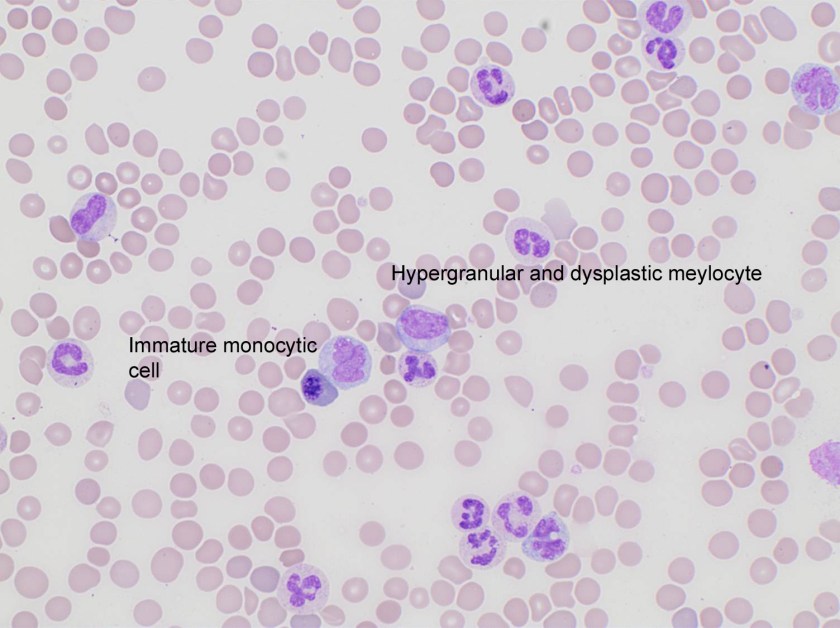

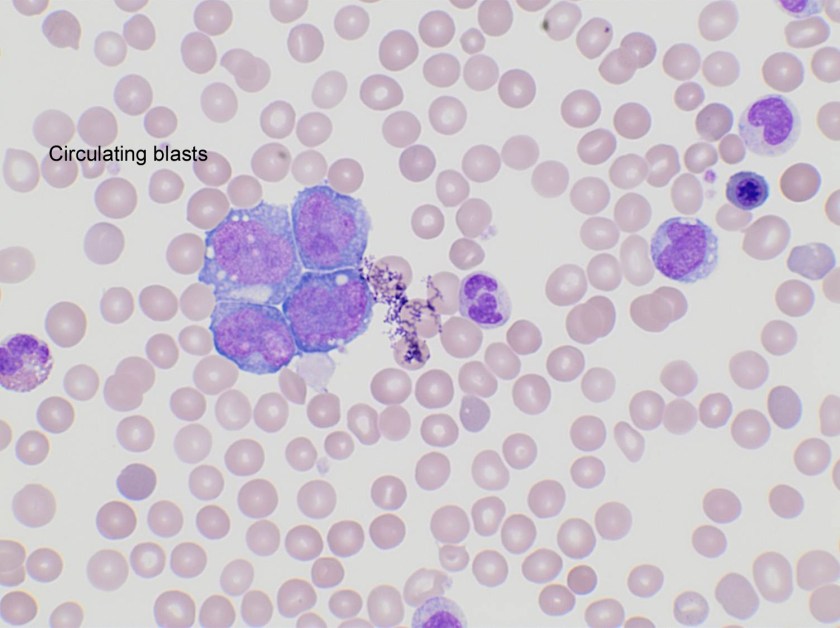

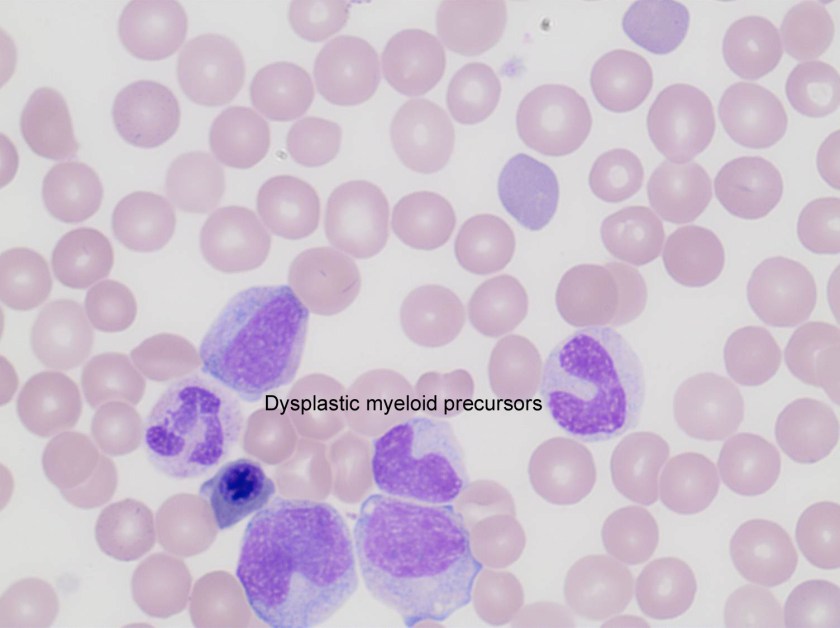

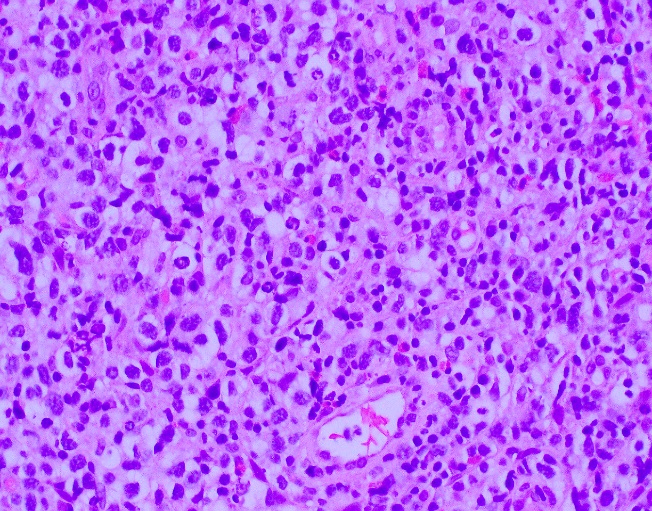

The core needle biopsy material demonstrated a lymphoid population that was polymorphic in appearance with medium to large sized lymphocytes with moderate amounts of pale cytoplasm, irregular nuclei, vesicular chromatin, and some cells with prominent nucleoli. The background cellular population is composed of a mixed inflammatory component including small lymphocytes, scattered neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.

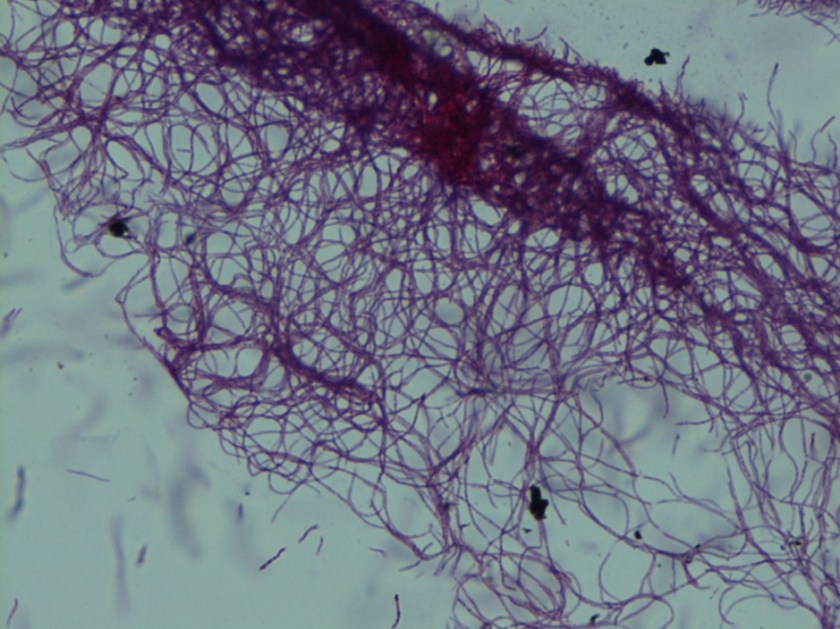

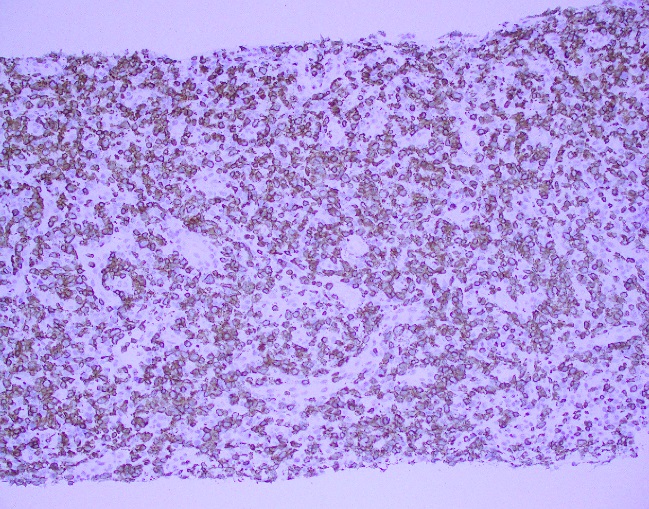

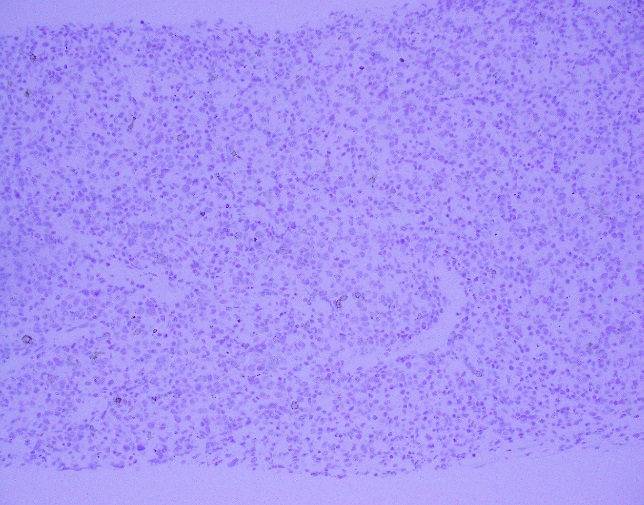

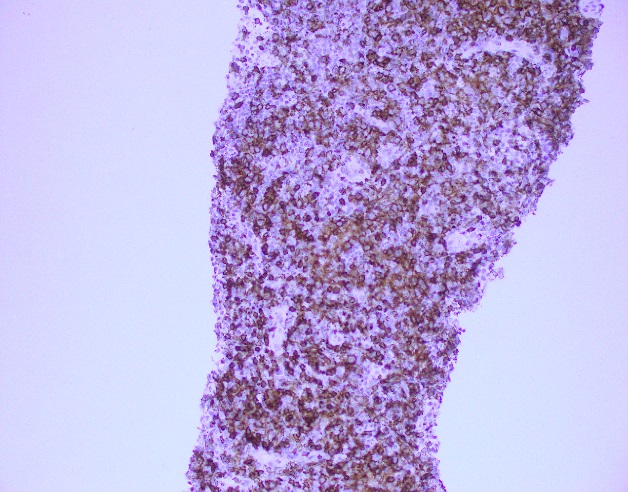

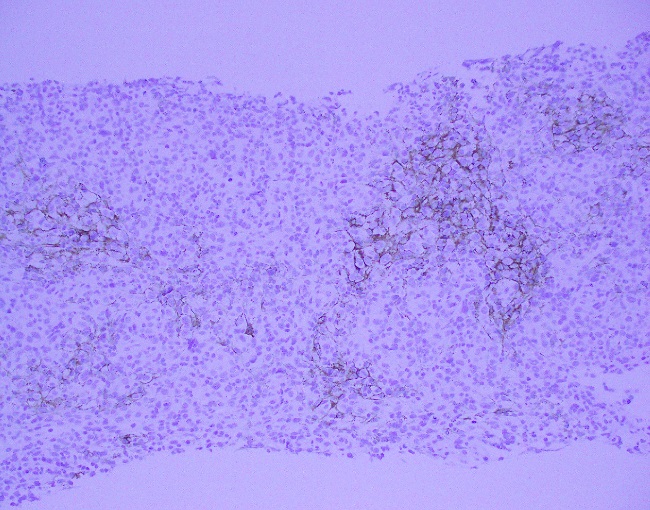

By immunohistochemistry, the medium to large sized cells with pale cytoplasm are positive for CD3, CD2, CD4, and CD5 with complete loss of CD7. CD20 highlights scattered background B-cells. CD21 is positive in disrupted follicular dendritic meshworks. CD10 and BCL6 are negative in neoplastic cells. PD1 is positive in neoplastic cells with a subset co-expressing CXCL13. By Ki-67 immunostaining, the proliferation index is 50-70%. By in situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNA, a subset of cells are positive.

Overall, with the morphologic and immunophenotypic features present, the diagnosis is that of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

Discussion

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is one of the most common types of peripheral T-cell lymphoma and accounts for 15-20% of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders and 1-2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Clinical features include presentation with late stage disease with associated generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, systemic symptoms, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Of note, this patient did have an SPEP that was within normal limits. Other findings, although less common, include effusions and arthritis. Laboratory findings often include cold agglutinins with hemolytic anemias, a positive rheumatoid factor (RF), and anti-smooth muscle antibodies. A hallmark of AITL is the expansion B-cells positive for EBV is seen, which may be an indicator of underlying immune dysfunction. The clinical course is often aggressive with a median survival of less than three years and often succumb to infectious etiologies because of an immune dysregulation.1

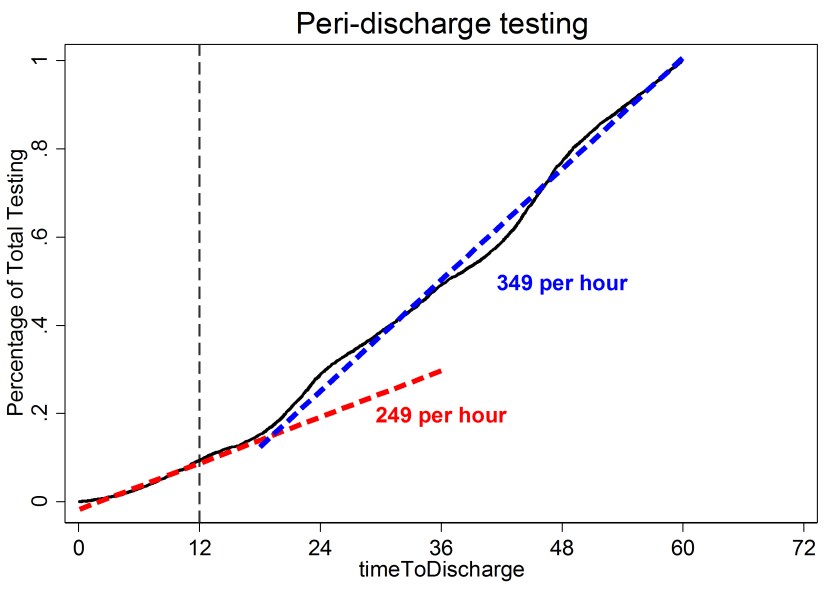

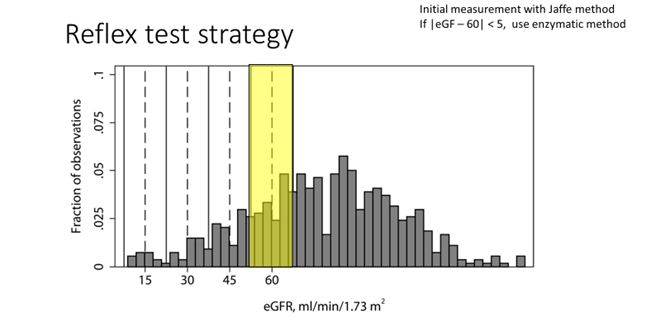

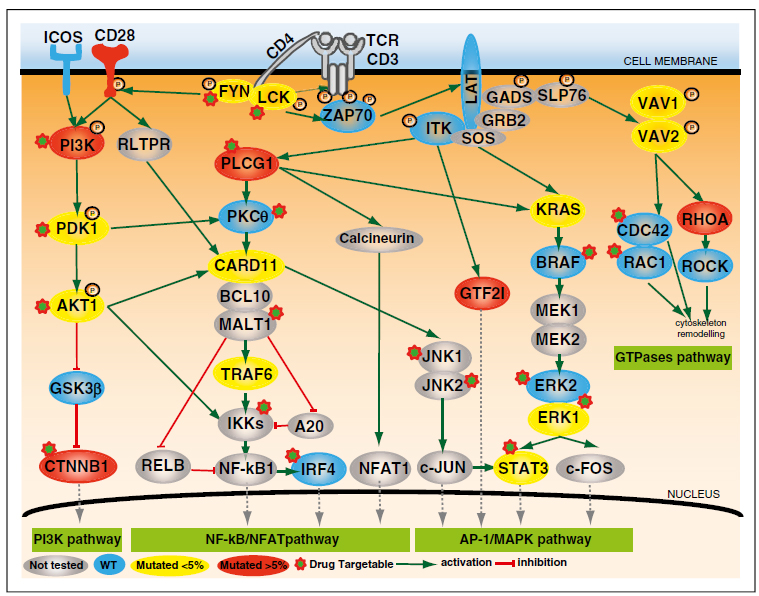

The pathogenesis and relation to other TFH neoplasms of PTCL, NOS is poorly understood. Recent literature indicates dysregulation in key pathways, including the CD28 and TCR-proximal signaling genes, NF-kappaB/NFAT pathway, PI3K pathway, MAPK pathway, and GTPases pathway.2 The complexity of these pathways has long been an issue for TFH lymphoproliferative disorders and has provided insight to potential molecular signatures (see figure 1 adapted from Vallois 2016).

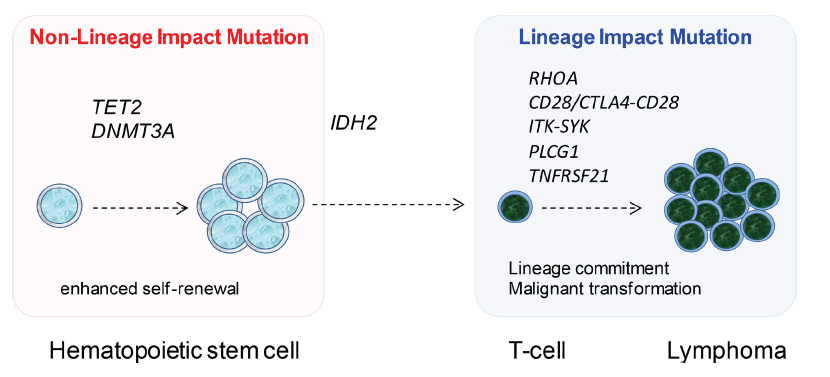

Another recent publication provided additional information regarding molecular insights. Confirmed mutational analyses reveals a high proportion of cases carry a TET2 mutation with less frequent changes in DNMT3A, IDH2, RHOA, and PLCG1. Specifically, RHOA, PLCG1, and TNFRSF21 encode proteins critical for T-cell biology and most likely promote differentiation and transformation into an aggressive clinical course (see figure 2 adapted from Wang 2017).3

Overall, AITL is an uncommon TFH cell derived lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by a TFH immunophenotype, expanded and arborizing high endothelial venules, expansion of the follicular dendritic cell meshworks, and EBV positive B-cells in a background of a polymorphic infiltrate. Although it is hypothesized that the underlying mechanism of neoplasia is related to immune dysfunction, new molecular insights have demonstrated that multiple events occur ranging from early molecular changes to later acquired mutations that allow for malignant transformation.

References

- Swerdlow, S., et al., WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th. ed., IARC press: 2008

- Vallois, D., et al. “Activating mutations in genes related to TCR signaling in angioimmunoblastic and other follicular helper T-cell-derived lymphomas,” 2016; 128(11): 1490-1502.

- Wang, M., et al., “Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma: novel molecular insights by mutation profiling,” 2017; 8(11): 17763-17770.

-Phillip Michaels, MD is a board certified anatomic and clinical pathologist who is a current hematopathology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well as pathology resident education, especially in hematopathology and molecular genetic pathology.