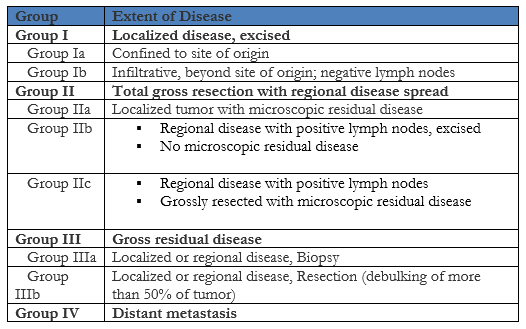

Case History

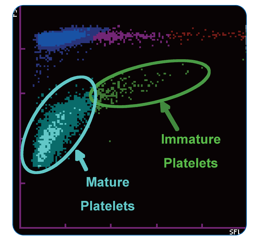

The patient is a 41 year old male with a history of smoking who presents with a tender, slowly growing mass on the angle of the left mandible for the past 1 to 1.5 years. The patient also complains of otalgia, but no dysphagia or weight loss. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which demonstrated a 3.2 x 2.6 cm enhancing mass in the superficial lobe of the left parotid gland with no significantly enlarged lymph nodes and a patent Stensen’s duct (Image 1). A fine needle aspirate (FNA) was performed that showed acinic and ductal cells, but was not diagnostic. The decision was made to take the patient to surgery in order to perform a parotidectomy.

Diagnosis

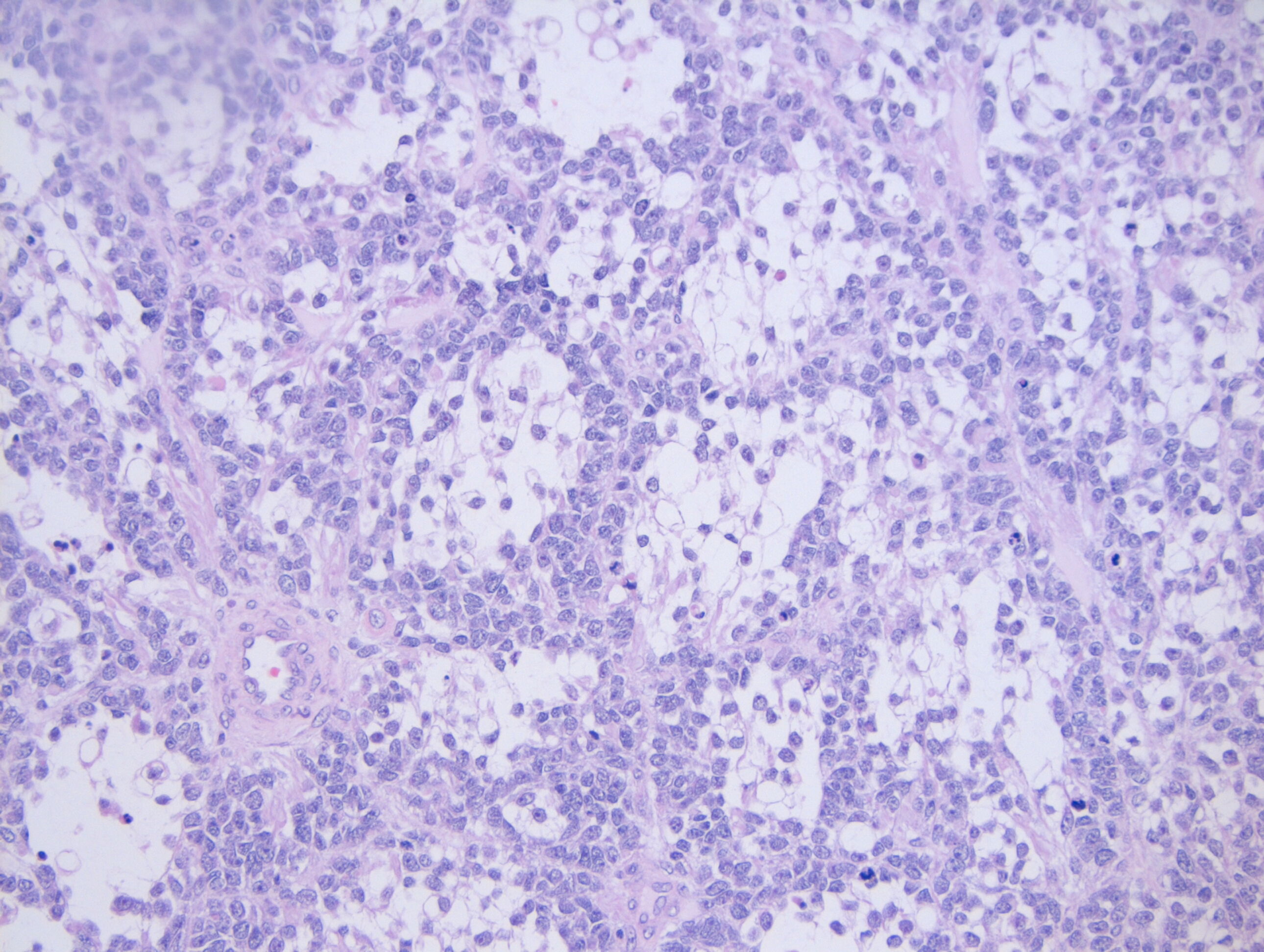

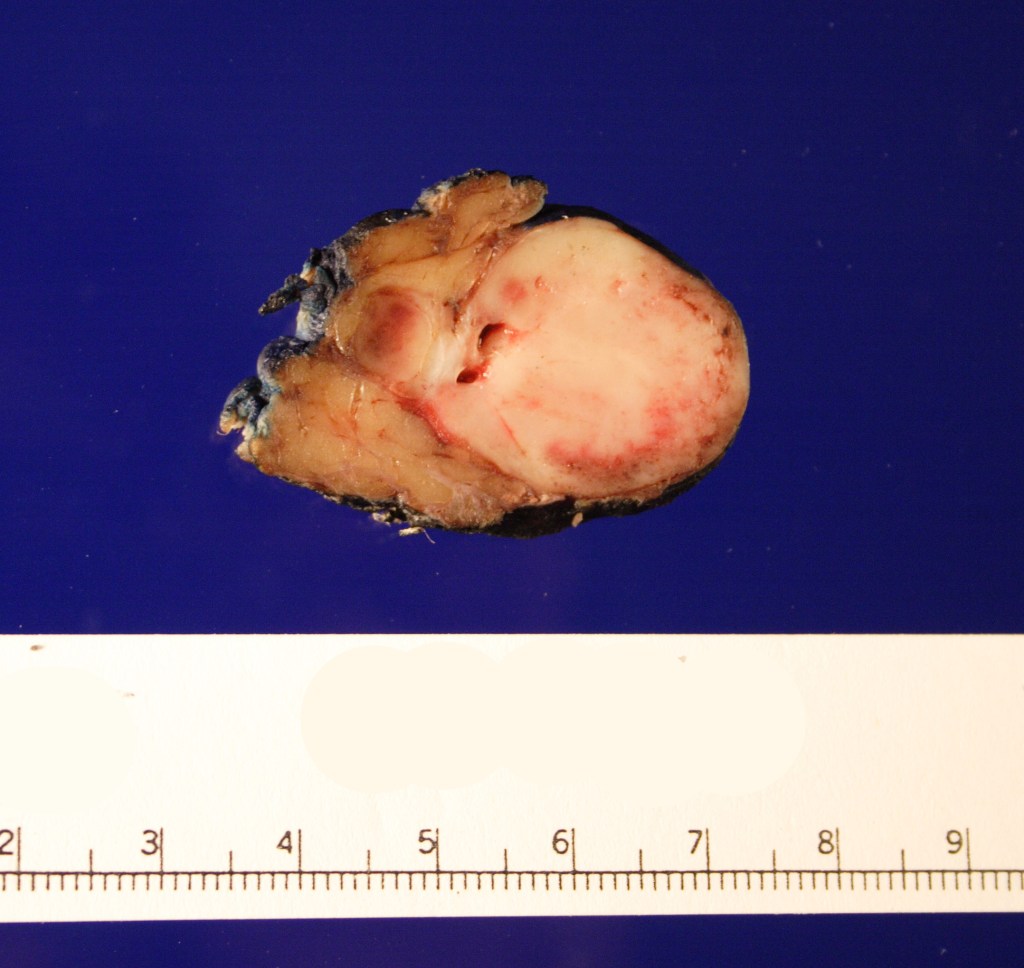

Received in the surgical pathology laboratory for intraoperative consultation was a 0.3 x 0.2 x 0.2 cm biopsy of the left superficial lobe parotid gland mass. The tissue was frozen, stained and read out as an “acinic cell neoplasm”. Following the frozen diagnosis, the main specimen was received for routine processing, weighing 19.0 gm and measuring 4.0 x 4.0 x 3.0 cm. The specimen was unoriented and entirely inked black. It was serially sectioned revealing a 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.4 cm tan, friable, well-circumscribed mass and surrounding tan-brown, beefy-appearing parotid tissue (Image 2). A second tan-brown nodule measuring 1.5 x 1.0 x 0.8 cm abuts the larger tan mass. Representative sections of the larger mass are submitted in cassettes 1-8, and the smaller nodule is entirely submitted in cassettes 9 and 10.

Microscopy demonstrates a low-grade, very well differentiated tumor consistent with an acinic cell carcinoma with complete inked surfaces (i.e. the mass has not been transected and excision appears complete). There is a small focus of capsular “disruption”/parenchymal hemorrhage, which most likely corresponds to the area sampled for intraoperative consultation. In addition, there are two separate benign periparotid lymph nodes.

Discussion

Acinic cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare tumor of the parotid gland, representing 2 to 4% of all primary parotid gland neoplasms. It is the second most common childhood salivary gland malignancy behind mucoepidermoid carcinoma, but has been found throughout the age range. There is a gender predilection, as ACC is found in females more than males in a 3:2 ratio. One of the first cases of ACC dates back to 1892, in which the tumor was diagnosed as being a “blue dot tumor”, thought to be called this due to the intracytoplasmic zymogen granules.

Clinically, ACC presents as a slowing growing mass in the salivary glands, most commonly in the parotid gland. Other symptoms are not commonly found until late in the diagnosis, and include pain, facial nerve palsy, and nodal disease. There have also been cases of ACC that arise in the minor salivary glands. Unlike minor salivary gland carcinomas that arise in the palate, ACC of the minor salivary glands will mostly be found in the buccal mucosa and upper lip.

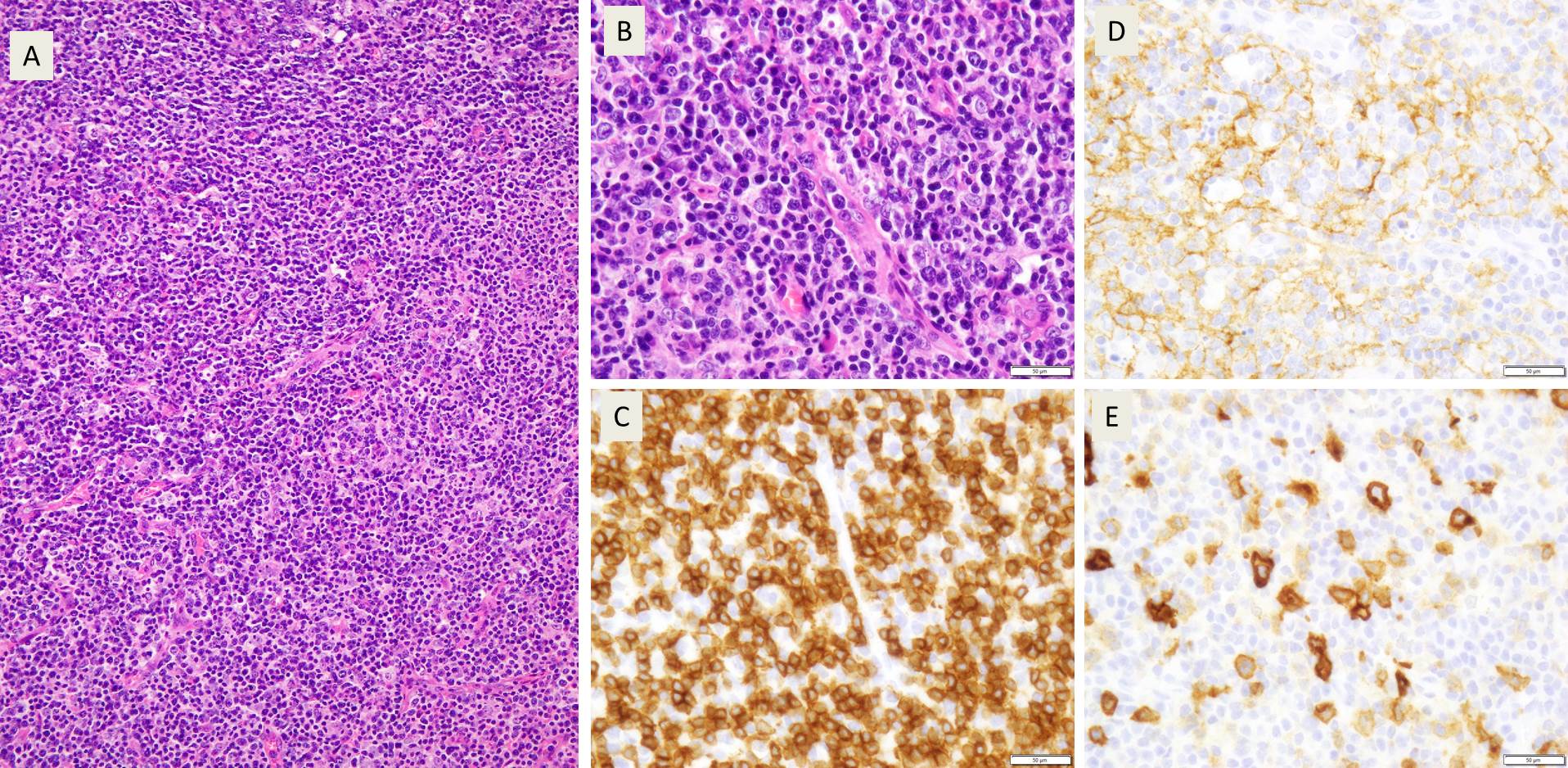

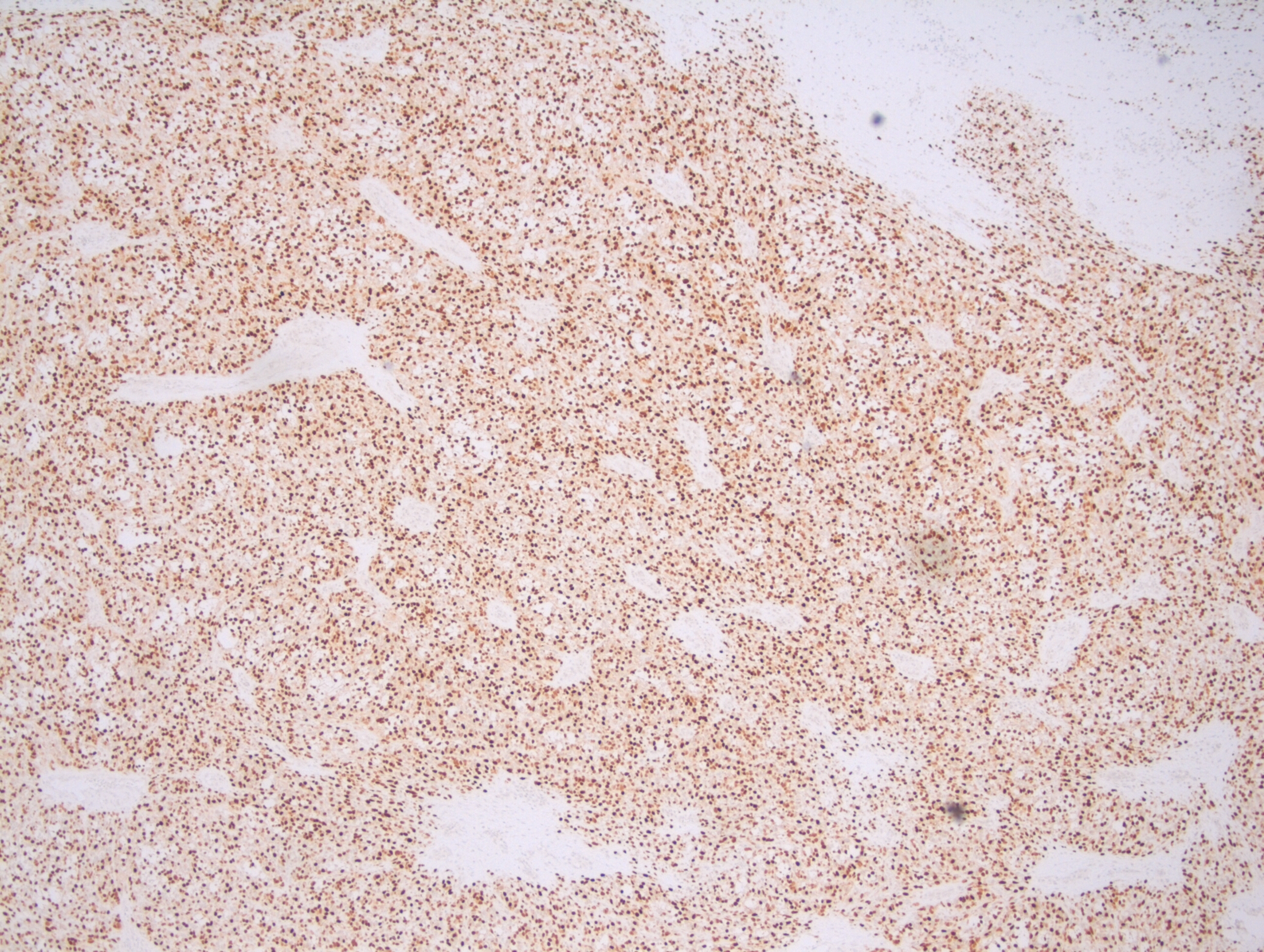

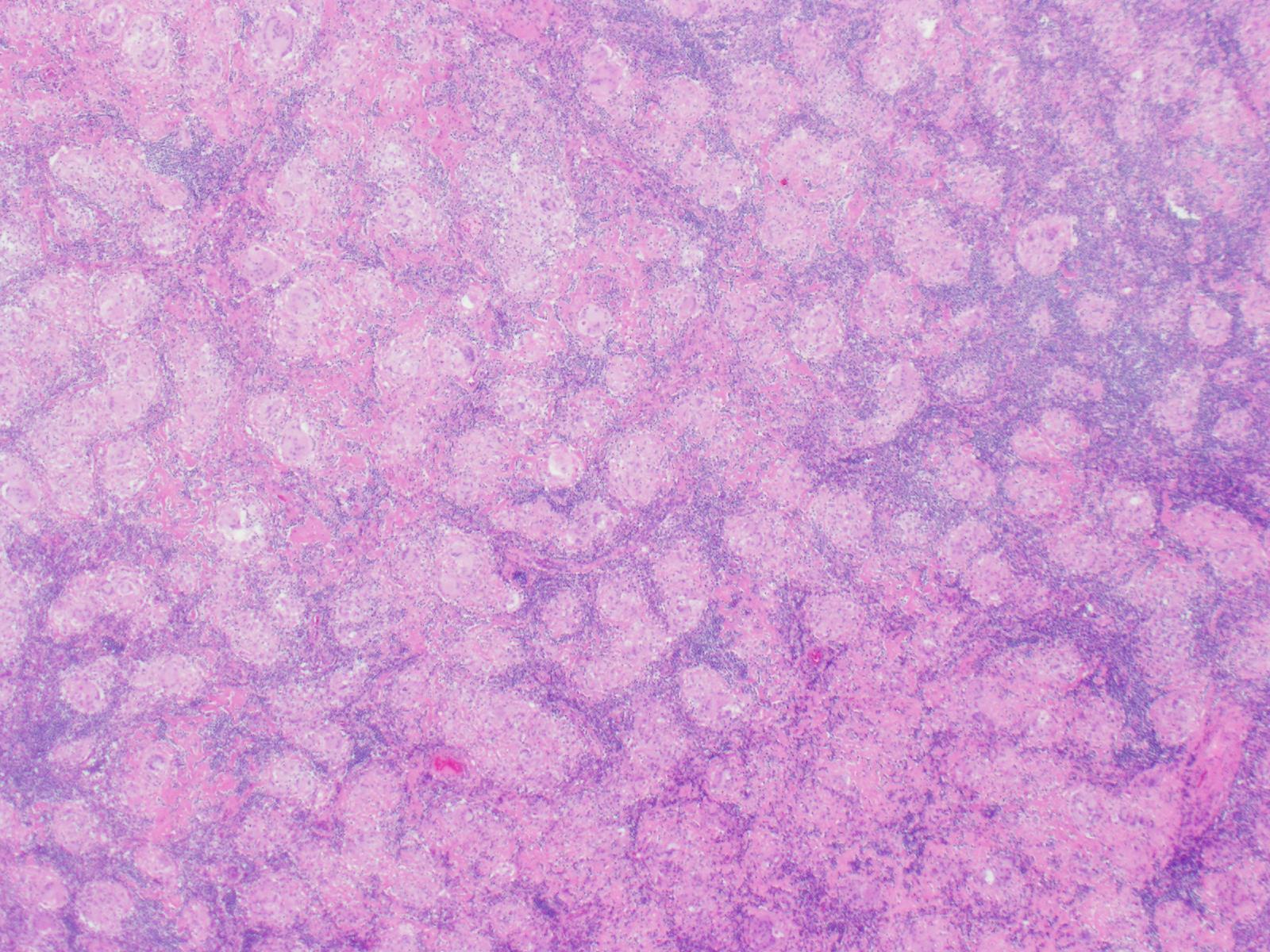

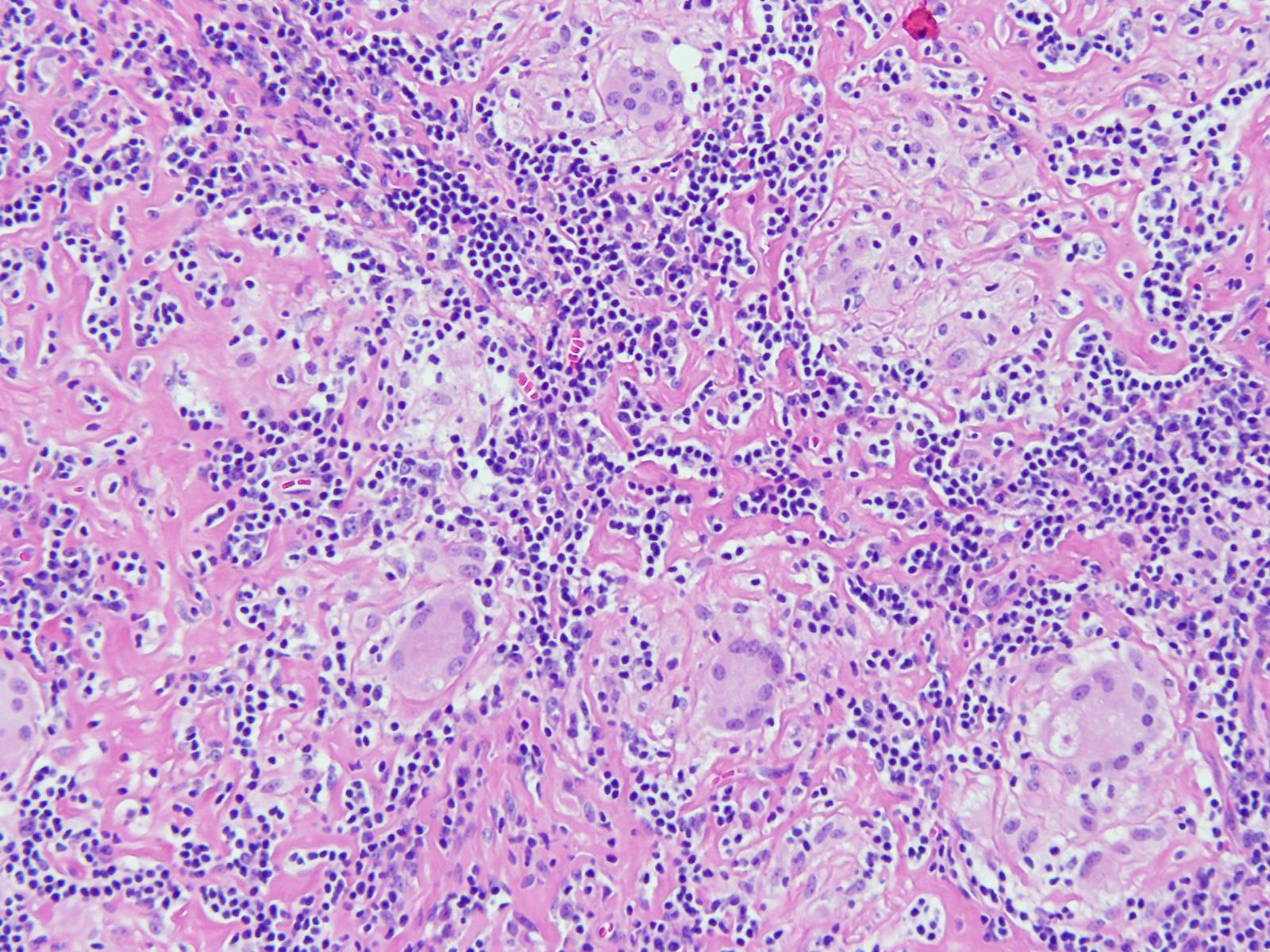

Grossly, ACC presents as a round, well-circumscribed to variably encapsulated mass with a rubbery, gray-tan, solid to cystic cut surface, commonly with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Histologically, the mass will be composed of acinar type cells with basophilic granular cytoplasm, clear cells with glycogen or mucin, intercalated ducts, non-specific glandular cells and a few mitotic figures. ACC is defined by the World Health Organization as a malignant epithelial neoplasm of the salivary glands in which at least some of the neoplastic cells demonstrate serous acinar cell differentiation, which is characterized by zymogen secretory granules, and can also include salivary ductal cells (Image 3). It is common for sections taken of ACC to show microscopic invasion of the capsule with nests of tumor cells outside the capsule. There are four histologic patterns that were described by Abrams et al in 1965 that are still applicable today: solid, microcystic, papillary cystic and follicular. Immunohistochemical stains, if needed, will be positive for keratin, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin and alpha amylase. It can be difficult to distinguish ACC from normal acini or benign salivary gland tumors (leading to a false negative result) on cytology due to the absence of any hallmark malignancy features such as necrosis and pleomorphism, but centrally placed large nuclei, distinct nucleoli, binucleated cells, and ill-defined cell borders can help make this distinction. The same caution applies to aspirates because if the tumor is cystic, it may be interpreted as being hypocellular and deemed to be a benign salivary cyst.

Imaging by ultrasound, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can prove to be worrisome as similar with cytology, the scans can demonstrate a mass with benign features, and thus a more favorable diagnosis. On ultrasound, ACC will appear lobular, well-defined, hypoechoic and poorly vascularized. Ultrasound can be useful help to determine the size and location of the mass, as well to help with ultrasound guided fine needle biopsies. On CT, the mass will appear non-specific with limited heterogenous enhancement but can be used to demonstrate the relationship of the mass to the facial nerve, and to identify any distant metastases. On MRI, ACC can have a nonspecific intensity pattern similar to benign salivary gland neoplasms, but low T1 and T2 signals can help suggest vascularity, fibrosis and calcification within the mass. In addition, MRI can help in assessing the parotid gland, stylomastoid foramen, and any possible facial nerve invasion or perineural invasion.

Risk factors for the development of ACC include radiation exposure and familial predisposition. Risk factors for the development of salivary gland tumors, but not necessarily ACC, include radiation exposure, the use of iodine 131 in the treatment of thyroid disease (isotope is concentrated in the salivary glands), and working with materials in certain industries, such as those that use asbestos and rubber manufacturing, metal in the plumbing industries, and woodworking in automobile industries.

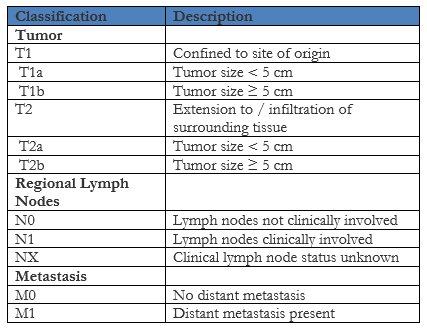

Complete surgical excision is considered the primary treatment option, with postoperative radiotherapy in cases of incomplete removal, recurrence, undifferentiated ACC, positive margins, and cervical lymph node metastasis. Removal of the facial nerve may be necessary in T3 and T4 cases, as well as a possible neck dissection. As of now, ACC has been considered chemo-resistant, and treatment with chemotherapy is not suggested. Around 35% of tumors will recur, and that percentage rises to 80-90% if the tumor is incompletely excised. ACC has a 5 year survival rate of 90%, a 10 year survival rate of 88%, and there have even been of cases of recurrence occurring up to 30 years after the initial procedure. If metastasis was to occur, although rare, the spread tends to be more hematogenous than lymphatic, with the most common sites being the lungs and bones.

References

- Al-Zaher N, Obeid A, Al-Salam S, Al-Kayyali BS. Acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary glands: a literature review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2009;2(1):259-64.

- Bury D, Dafalla M, Ahmed S, Hellquist H. High grade transformation of salivary gland acinic cell carcinoma with emphasis on histological diagnosis and clinical implication. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212(11):1059-1063. DOI: 10.1016/j.prp.2016.08.005.

- Rosero DS, Alvarez R, Gambó P, et al. Acinic Cell Carcinoma of the Parotid Gland with Four Morphological Features. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11(2):181–185.

- Vander Poorten V, Triantafyllou A, Thompson LD, et al. Salivary acinic cell carcinoma: reappraisal and update. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(11):3511-3531. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-015-3855-7

- Zahra Aly F. Acinic Cell Carcinoma. Pathology Outlines. http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/salivaryglandsaciniccell.html. Revised April 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2019.

-Cory Nash is a board certified Pathologists’ Assistant, specializing in surgical and gross pathology. He currently works as a Pathologists’ Assistant at the University of Chicago Medical Center. His job involves the macroscopic examination, dissection and tissue submission of surgical specimens, ranging from biopsies to multi-organ resections. Cory has a special interest in head and neck pathology, as well as bone and soft tissue pathology. Cory can be followed on twitter at @iplaywithorgans.