Case History

A 73 year old man was brought to the emergency room with altered mental status and fever, which developed a few days following a 1-2 day illness characterized by myalgia and diarrhea. He was admitted to the hospital and blood cultures were drawn.

Laboratory Identification

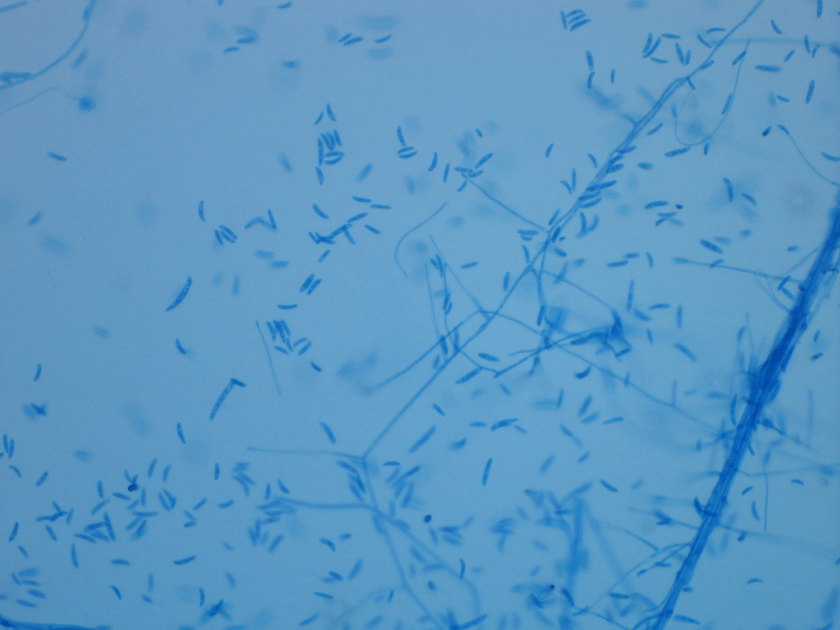

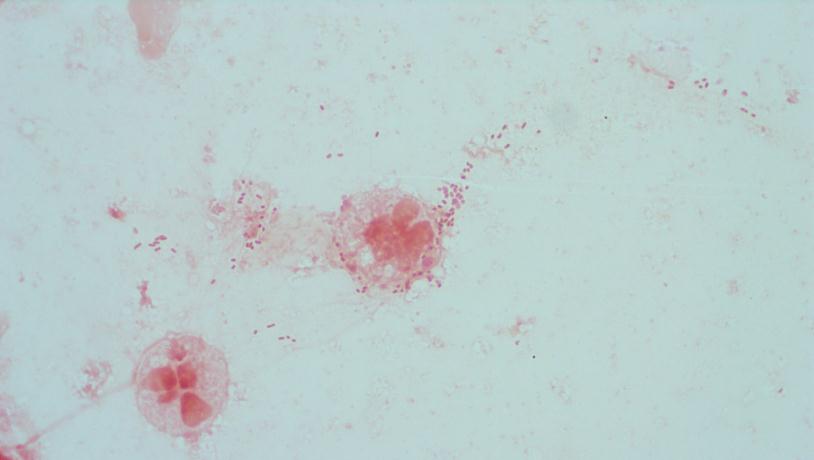

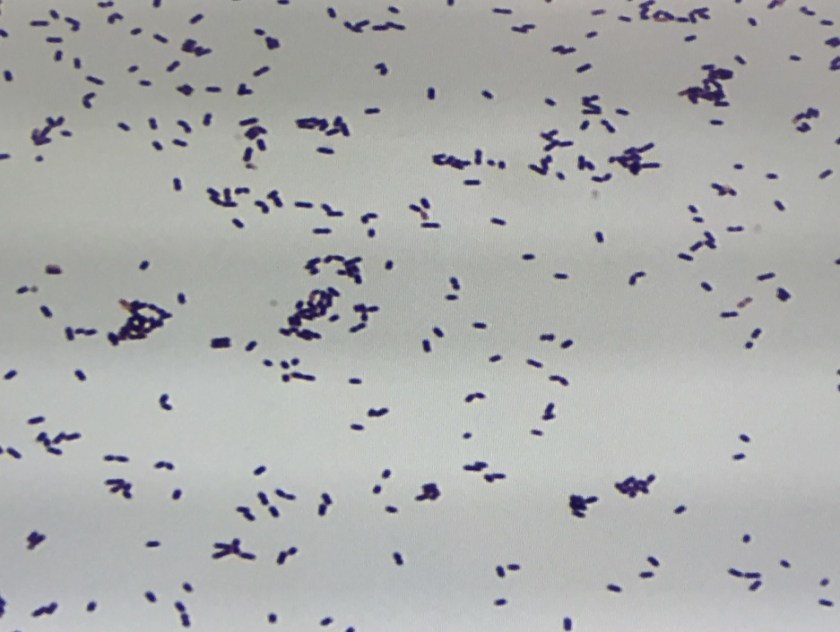

The bottles flagged positive after 12 hours and Gram stain showed small, Gram positive rods (Figure 1). Growth of white, smooth translucent colonies was seen on the blood and chocolate plates, with a small rim of beta-hemolysis on the blood plate (Figure 2). MALDI-TOF confirmed the identification as Listeria monocytogenes.

Figure 1. Gram stain morphology of the colonies growing, demonstrating short Gram positive bacilli.

Figure 2. Smooth white colonies growing on the blood and chocolate plates, with a soft rim of beta-hemolysis visible on the blood plate.

Discussion

Listeria monocytogenes is prevalent throughout the environment, and can also colonize the human gastrointestinal tract. Humans are exposed by consumption of contaminated food, particularly soft cheeses, deli meats, and fruit. Listeria can grow at 4C which means it can multiply in refrigerated foods, making even low-level contamination a potential hazard. On gram stain, it is a short gram positive rod which may form chains. In some cases, the rods may be so short as to resemble chains of Streptococci, and with the soft surrounding beta hemolysis, could potentially be confused for Group B Streptococcus. However, Listeria is catalase positive, while Group B Strep is negative. Another characteristic feature of Listeria is the “tumbling motility” on wet prep at 20-25C, or “umbrella motility” in tube agar. Listeria also has the unique feature of manipulating the host cells’ intracellular actin framework, using it to facilitate direct cell-to-cell spread of the bacteria. The main virulence factor is the listeriolysin toxin, which is postulated to permit survival of the organism within macrophages via cytotoxic activity.

Listeria can cause a self-limited febrile gastroenteritis in previously healthy individuals, but typically only if they consume a large inoculum. However, in neonates, the elderly, or the immunosuppressed, it can invade and cause sepsis, meningitis, or meningoencephalitis. In pregnant women, Listeria can cross the placenta and lead to intrauterine fetal demise, premature labor, or neonatal meningitis, as well as the typically fatal condition granulomatosis infantiseptica in which the newborn develops widespread abscesses throughout multiple organ systems. Infection during pregnancy usually happens during the 3rd trimester, though the effects seem to be more severe with earlier infection.

Listeria has been cultured from the stool of up to 3.4% of healthy, asymptomatic humans, and so there is little utility in stool cultures for Listeria except for epidemiologic purposes during an outbreak. Infections due to outbreaks of Listeria are far less common than sporadic infections, which comprise 95% of Listeria infections. Additionally, traditional stool cultures are poor at detecting Listeria and selective media is usually required. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid are the preferred sites of culture if there is suspicion for disseminated infection. Meningitis caused by Listeria is unique in that is can cause a lymphocyte-predominant CSF pleocytosis, which may result in confusion for viral meningitis. Additionally, gram stains of the CSF are only positive in approximately 1/3 of patients, so a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained while awaiting final culture results. While antibiotic treatment is not recommended for otherwise healthy patients with febrile gastroenteritis, it is recommended for those with disseminated infection or at high risk of dissemination (i.e. extremes of age, immunocompromised, or pregnant).

-Alison Krywanczyk, MD is a 3rd year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

-Christi Wojewoda, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and an Assistant Professor at the University of Vermont.