Case History

A thirty year old female with refractory acute leukemia was admitted to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Her initial admission had multiple infectious complications and chemotherapy-induced pancytopenia with profound absolute neutropenia. The patient was placed on prophylaxis/therapy including bacterial, viral, and fungal coverage. On hospital day 14, the patient was febrile to 38°C; vancomycin/piperacillin-tazobactam were added as empiric therapy due to concern for sepsis with fluctuation in mental status. CT Brain without contrast revealed a large intracranial hematoma with mass effect. Her mental status continued to decline and intubation was required for airway protection. An emergent decompressive hemicraniectomy was performed where necrotic brain tissue with hemorrhage/clot were found.

Due to ongoing fevers, empiric antimicrobial therapy was further broadened with meropenem, doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB). Repeat cultures and imaging studies were ordered to evaluate for infection as a fever source. CT Angiography Chest (Image 1A-C) was performed and revealed an extensive non-enhancing area of ground glass opacity with peribronchovascular consolidation (“Reversed Halo” sign) in the right lung concerning for angioinvasive fungal infection. A tracheal aspirate was sent for bacterial and fungal culture. Subsequent bronchoscopy revealed extensive necrosis involving all visualized airways of the right tracheobronchial tree to the first subsegmental level (Image 1D). By contrast, the left lung appeared relatively normal and uninvolved. Bronchial washings of the right lung were also submitted for culture.

Laboratory Identification

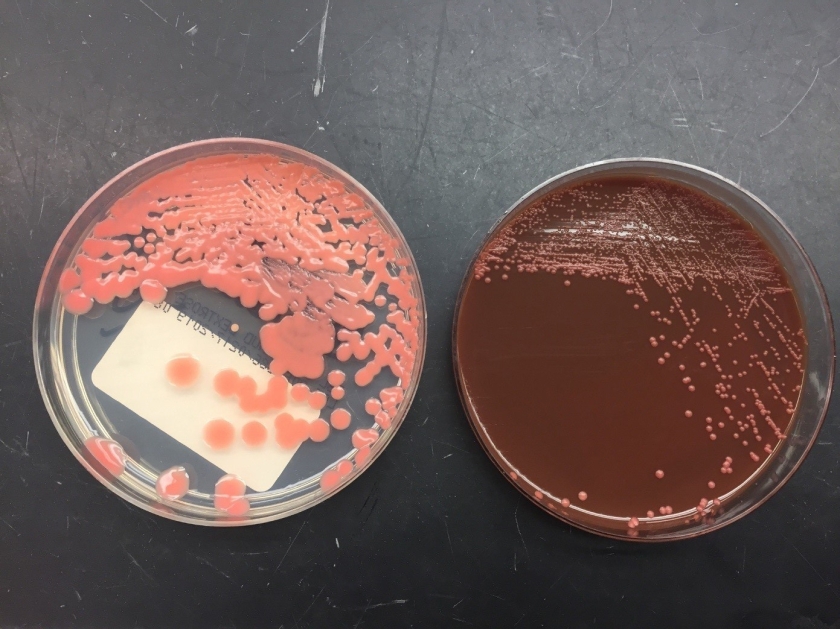

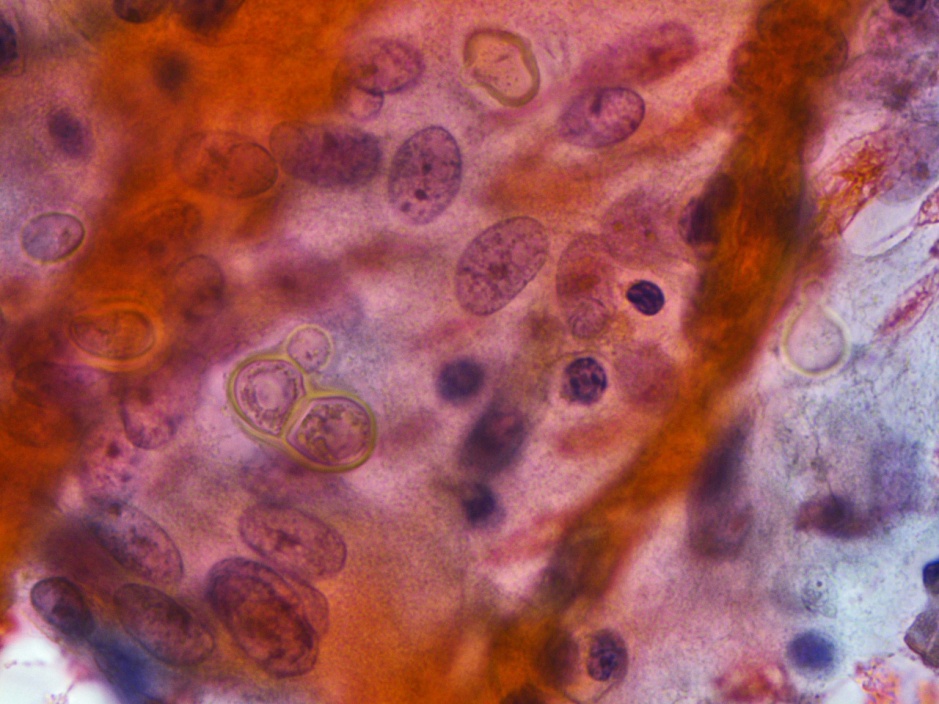

Respiratory specimens were sent to the microbiology laboratory for bacterial and fungal cultures. Hyphal elements were observed on the Gram stain of the submitted tracheal aspirate (Image 2A). Robust fungal growth was noted within 48 hours on Brain Heart Infusion and Inhibitor Mold agars from both the tracheal aspirate and bronchial wash specimens (Image 2B). A lactophenol cotton blue prep revealed broad hyphae with few septations, consistent with a member of the Mucorales (Image 3). Sporangiophores were noted to be long, dark and branched with round sporangia. Few rhizoids were observed and located between the sporangiophores. A definitive identification of Rhizomucor sp. was obtained through the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS).

Discussion

Members of the order Mucorales can be identified in the laboratory by their rapid, robust growth and cotton candy-like appearance on conventional fungal media excluding those containing cycloheximide.2 Microscopically, these molds exhibit pauciseptate, broad (9-15 μm wide) hyphae with sporangia. Some species elaborate root-like structures called rhizoids (e.g Rhizopus, Rhizomucor) while others lack them (e.g. Mucor).2 Rhizomucor sp. can be differentiated microscopically from other related members of the Mucorales by its branched, dark brown sporangiophores with absent apophysis, round columella and the presence of few, short, rudimentary rhizoids (Image 3A-D). In practice, the rhizoids can be challenging to identify microscopically.2 Some species can also grow at elevated temperatures (~38-58°C) which can be utilized as a tool for use in identification.2 Newer methods including the use of MALDI-TOF MS and DNA probes allow for rapid, accurate identification of these fungi, but are not routinely available in all laboratories.

Infections caused by Mucorales (Mucormycosis) usually involve immunocompromised patients with defects in cell-mediated immunity. Rapid and often fatal, these infections can prove extraordinarily difficult to manage. They are known to be angioinvasive and can widely disseminate. Debridement of involved tissues and higher-level antifungal agents (e.g. posaconazole, amphotericin B) are mainstays of therapy. The most recognized group of patients where these infections are identified are uncontrolled diabetics, frequently in diabetic ketoacidosis, often with nasal/orbital sinus involvement. Patients with leukemia/lymphoma who are undergoing stem cell transplantation are another group often affected. In addition to the nasal/orbital sinuses, the gastrointestinal tract, skin and lungs also serve as important sites for these infections, especially if mucositis occurs.1

Rhizomucor sp. are an occasional cause of mucormycosis, but have a predilection for leukemic patients such as in this case.2 Given the significant bronchoscopy findings and the intraoperative presence of necrotic brain tissue, there was substantial clinical concern for invasive pulmonary mucormycosis with possible central nervous system involvement. Isavuconazole was discontinued, and posaconazole and micafungin were added to her antifungal therapy (L-AMB). Granulocyte infusions were used in an attempt to increase her cell-mediated immune response to the mold. Cardiothoracic surgery evaluated the patient but the lesion was deemed unresectable. Due to the presence of epistaxis, the otolaryngology service evaluated the patient for invasive fungal sinusitis; however, nasal endoscopy did not reveal any nasal/sinus involvement. The patient never regained significant neurological function and continued to medically decline during the hospitalization. She was placed on comfort care where she died shortly afterwards.

References

- Love GL, Ribes JA. 2018. Color Atlas of Mycology, An Illustrated Field Guide Based on Proficiency Testing. College of American Pathologists (CAP), p. 244-274

- Walsh TJ, Hayden RT, Larone DH. 2018. Larone’s Medically Important Fungi, A Guide to Identification. ASM Press, p. 185-190

-John Markantonis, DO is the current Medical Microbiology fellow at UT Southwestern and will be completing his Clinical Pathology residency in 2022. He is also interested in Transfusion Medicine and parasitic diseases.

–Kim Stewart BS, MT(ASCP)SM holds a bachelor’s degree from Texas Tech University and is medical technologist in the microbiology section at UT Southwestern Medical Center with 35 years’ experience.

-Andrew Clark, PhD, D(ABMM) is an Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in the Department of Pathology, and Associate Director of the Clements University Hospital microbiology laboratory. He completed a CPEP-accredited postdoctoral fellowship in Medical and Public Health Microbiology at National Institutes of Health, and is interested in antimicrobial susceptibility and anaerobe pathophysiology.