Contrary to common belief, the group is NOT as strong as the weakest link. Instead, a group is as strong as its capacity to compensate for the weakest link. We have all experienced this when, for example, a colleague does not do their share for a presentation or project. This does not mean that the project or presentation fails; it means that other team members will compensate and do additional work that was initially assigned to the unproductive team member. The group thus does not sink to the level of the unproductive member. Instead, it rises to the level of how well others can do that members’ job.

When teams reach synergy, they reach a high level of effectiveness and productivity. In order to find out if your team is synergistic, this course conducts a simulation. The team-building simulation, designed by Human Synergistics International, revolves around some type of emergency situation: people are stranded in the desert, a tsunami is coming, they are surrounded by incoming bush fire, there is a severe snowstorm on the way, or people are stranded on a float plane in the middle of the subarctic. Through a video story, participants of this course are introduced to their situation and then asked to rank available items in order of importance. This is first done individually and then with a group while being observed by one person who is assessing their discussion. Once the correct ranking is revealed, participants will see the difference between their individual and group scores and they receive insights about how effectively they worked together.

Understanding the challenges of a team and how to move ineffective behaviors to productive ones is essential for team synergy. This course follows the Human Synergistics circumplex, explained in more detail in the Organizational Savvy and Reacting to Change course blog. In short, this circumplex indicates which behaviors are constructive, passive/defensive or passive/aggressive. Awareness of the constructive and ineffective behaviors will increase a team’s synergy. The idea behind this model is that when a team adopts constructive behavior, their collaborative results will produce greater results than the sum of their individual efforts. These groups are not as strong as their weakest link, nor are they as strong as their capacity to compensate for the weakest link. Rather, these groups are as strong as their syngeristic capacity.

-Lotte Mulder earned her Master’s of Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 2013, where she focused on Leadership and Group Development. She’s currently working toward a PhD in Organizational Leadership. At ASCP, Lotte designs and facilitates the ASCP Leadership Institute, an online leadership certificate program. She has also built ASCP’s first patient ambassador program, called Patient Champions, which leverages patient stories as they relate to the value of the lab.

“Doctor! We need your help STAT … in Antarctica!”

As a pathologist based in Denver, Colorado, I can easily say this is not a statement I ever expected to hear. Because of my sub-specialty expertise in surgical and cytopathology, and my role as chairman of the pathology department in a tertiary care facility, it was not unusual for colleagues, staff and administrators to stop by my office or to phone me for a matter in need of immediate attention. The conversation would usually start with, “Doctor Sirgi, we need your help as soon as possible with …”. I always welcomed these opportunities to assist with whatever matter needed attention, knowing full well the ultimate beneficiary of these calls would be a patient or an anxious family member. However, I could not hide my surprise when I heard the second part. “You need me where?!” I asked, thinking I had misheard the latter part of the phrase. It turns out my assistance really was immediately needed in Antarctica!

That moment in June 1999 I learned the headquarters of Antarctic Support Associates (ASA) is based in Englewood, Colorado (a suburb of Denver). ASA is contracted by the National Science Foundation to provide science support to the United States Antarctic Program (USAP), based at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station (ASSPS). The ASA director told me they had received a desperate call from the scientific team deployed in the South Pole informing them their only medical doctor on site, Dr. Jerri Nielsen, had discovered a breast lump worrisome for cancer during self-palpation. Considering Antarctica was in deep winter, with outside temperatures hovering around negative 85 degrees Fahrenheit evacuating the doctor for medical tests and treatment was completely impossible. This was a full-fledged “Houston we have a problem!” kind of situation.

As soon as I arrived at ASA, a videoconference was established with the afflicted doctor and a few non-medical scientists on site via satellite link-up; the first order of business was to understand the elements of the problem and offer a potential course of action. We only had a few precious minutes of satellite connection before lost of signal. We learned the following:

- The doctor had self-detected a sizable breast mass of hard consistency.

- Nobody around her had any experience at performing a biopsy or fine needle aspiration, let alone surgery.

- There was no laboratory facility or expertise to offer pathology examination, should a sample be obtained.

- There was no mammography or ultrasound equipment adequate for the evaluation of a breast mass.

- There was no adequate medication, should a diagnosis of malignancy be established.

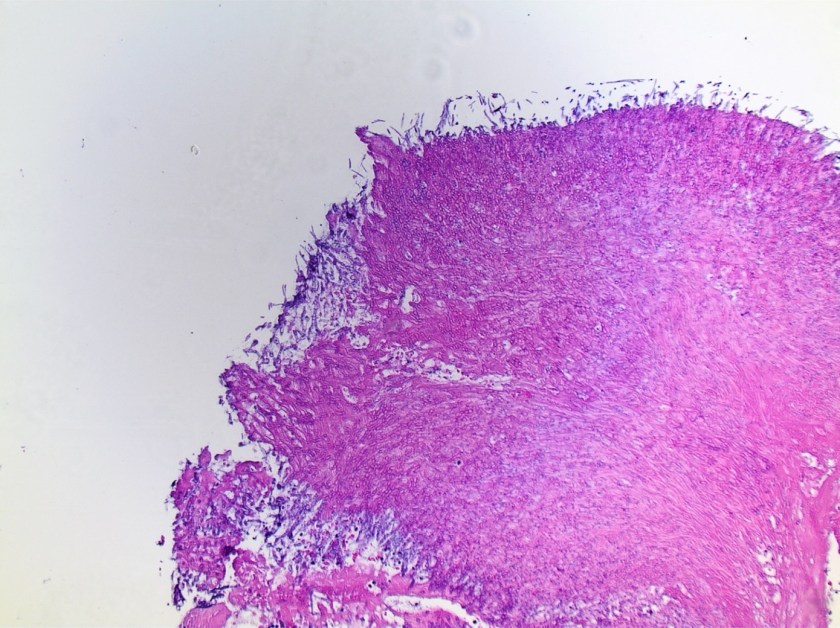

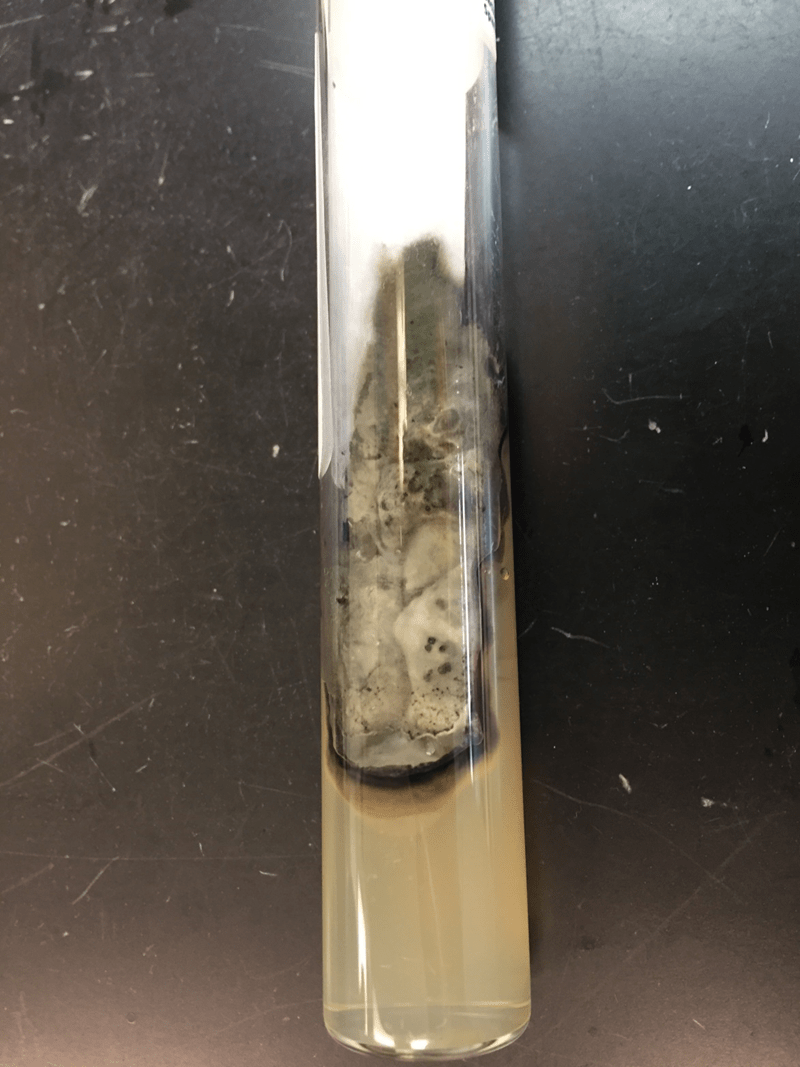

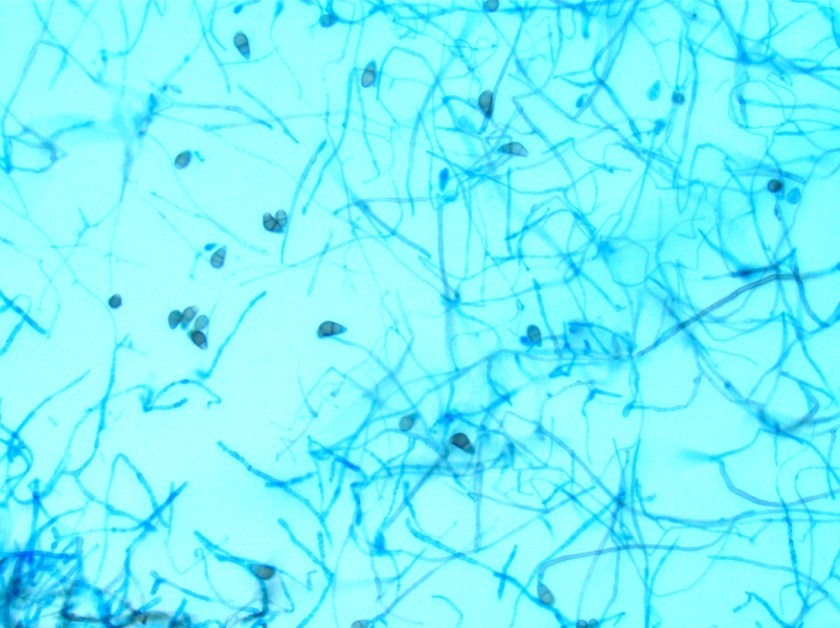

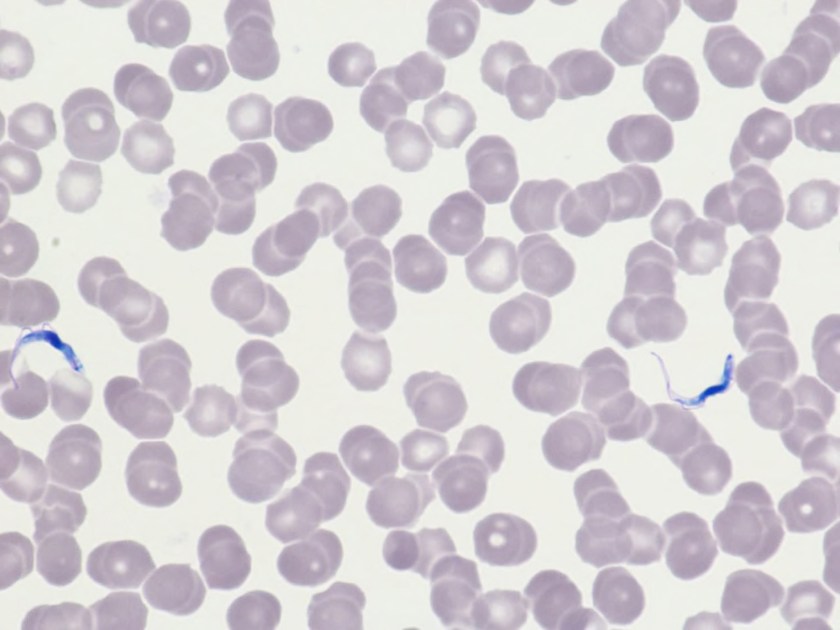

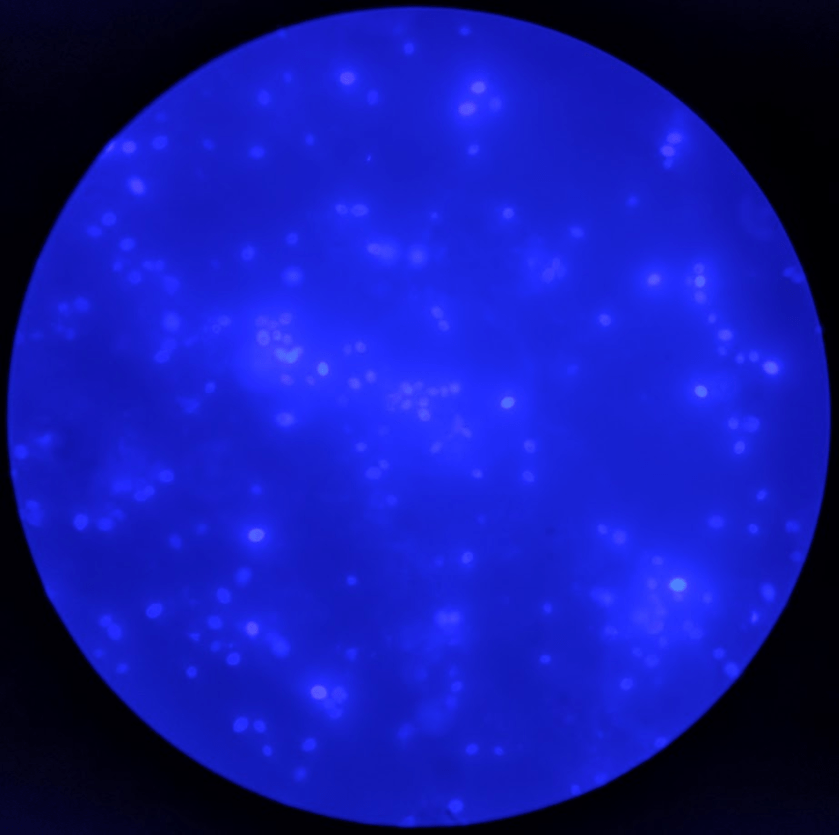

With the possibility (or the wishful thinking) that we could still be dealing with a benign lesion, I recommended that we first focus our efforts on securing a diagnosis. Luckily, the rudimentary equipment available to Dr. Nielsen included needles, glass slides, Giemsa stain, an antiquated microscope (with no camera attachment), and a medium resolution digital camera borrowed from scientists working in another area of the research facility. I explained in detail to Dr. Nielsen and her team of worried volunteers how to use these seemingly unrelated pieces of material and equipment. Keep in mind that all this happened at a time when digital pathology was still in its infancy (if not fetal stage), and a hefty dose of DIY had to be improvised on the spot.

I had brought a needle, an orange, a couple of glass slides, and three jars filled with the fluids needed for a quick staining of the material obtained. Dr. Nielsen had herself and her crew of non-medical scientists. I demonstrated how to perform a fine needle aspiration, smear the material obtained on a glass slide, and how to properly stain it for microscopic examination.

These were but the very first steps of a long journey toward obtaining a diagnosis. Considering Dr. Nielsen had no expertise in the examination of pathology material, she needed to follow steps completely unfamiliar to her in order for me (and other experts mobilized around the country) to establish a diagnosis:

- Perform a medical procedure she had never performed before … on herself!

- Prepare smears of the material aspirated from the mass

- Have those smears stained

- Use a microscope to identify areas of cellularity on the slides obtained

- Use a camera to take pictures of these areas

- Load the pictures in an email

- Transmit an email “heavy in data” across the planet, on a very slow satellite linked connection

Dr. Nielsen performed the procedure on herself the next day. The pictures I received a day later were impossible to interpret because the slides had been improperly stained; areas photographed had abundant red blood cells but no breast epithelial cells to evaluate. The team was understandably quite discouraged when they received our feedback. I sent them an email commending them on their efforts and further guiding them on:

- Troubleshooting the staining process

- Focus on the best areas to take pictures, using a breast cytopathology atlas as a visual aide

Their second attempt was much improved and allowed us to unequivocally establish a diagnosis of malignancy affecting Dr. Nielsen’s breast. Reaching a diagnosis was good; however, the tragic reality still remained that the patient had cancer and it was completely impossible to evacuate her from her current location.

The “home team” (anybody not based on the other end of the world) immediately started mobilizing resources from different areas of expertise to:

- Get Dr. Nielsen the treatment she needed while stuck in Antarctica

- Get Dr. Nielsen out of the South Pole as soon as meteorological conditions allowed

The following immediate priorities were then identified and acted upon:

- Per the oncologists consulted, adequate chemotherapy could not be started in the absence of knowing the tumor’s biomarkers status

- To establish this status, better tissue was needed for further immunohistochemical testing

- Each medical specialty involved with the rescue effort made recommendations for the type of equipment and material that needed to be transported to the South Pole (including specialized medical atlases, ultrasound equipment, newer microscopes equipped with high resolution digital cameras, regular and immunohistochemical stains with appropriate easy to use instructions, various chemotherapy drugs for different treatment possibilities).

The equipment, with duplicate units of everything sent, was placed in crates and flown to the US Air Force base in New Zealand. Ace pilots volunteered to drop the equipment over the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, despite terrible weather conditions, zero visibility over the drop zone, and no chance of landing or refueling during the mission. Ultimately, a couple of attempts were necessary to successfully drop the needed equipment over the area. The station personnel worked for hours in negative 85 degrees Fahrenheit temperatures and near zero visibility to collect the dropped material, much of it severely damaged, and transport the surviving equipment back to the base.

Treatment began, the tumor was stabilized, and Dr. Nielsen returned to the U.S., where she continued treatment as soon as weather allowed it. Unfortunately, she succumbed to her illness several months later.

What started as a “Dr. Sirgi, we need your help STAT … in Antarctica” developed into a medical rescue mission of monumental proportion. Ordinary people from different walks of life and medical expertise worked synergistically to develop on-the-fly life-saving solutions that had never been tried before. In the end:

- A heroic doctor performed diagnostic procedures on herself and braved all kinds of challenges in an attempt to survive.

- A staff of scientists with limited to no medical experience rose to the occasion to act as capable and devoted medical assistants.

- Physicians and medical technologists from around the country, who were previously strangers, synergistically worked together to coordinate efforts to save a colleague who was trapped in some of the harshest conditions in the world.

- Administrators of the Antarctic Support Associates (ASA) organization worked day and night to secure any and all expertise and needed equipment for the rescue mission.

- Air Force pilots voluntarily risked their lives to rescue a fellow human being.

No one involved woke up on that first day thinking they would be called for such a noble endeavor. All parties involved were ordinary citizens, and every single one tapped into his or her infinite leadership potential to collaborate with colleagues in order to resolve an almost impossible situation. Although There were many links of uncertain strength in this effort due to lack of experience or expertise, the common resolve and demonstrated leadership of all players involved created an indestructible chain of potential and led ultimately to the mission’s resounding success.

-Karim E. Sirgi, MD, MBA is board certified in anatomic and clinical Pathology, with additional board certification in cytopathology. He is active as an independent healthcare consultant, and is the current president of the CAP Foundation. Additional biographical information can be accessed at www.karimsirgimd.com