Readers of this blog presumable like laboratory medicine. If you also like listening to podcasts, check out Lab Medicine’s podcast series on iTunes.

Category: pathology

Hematopathology Case Study: A 45 Year Old Male with Mediastinal Mass

Case History

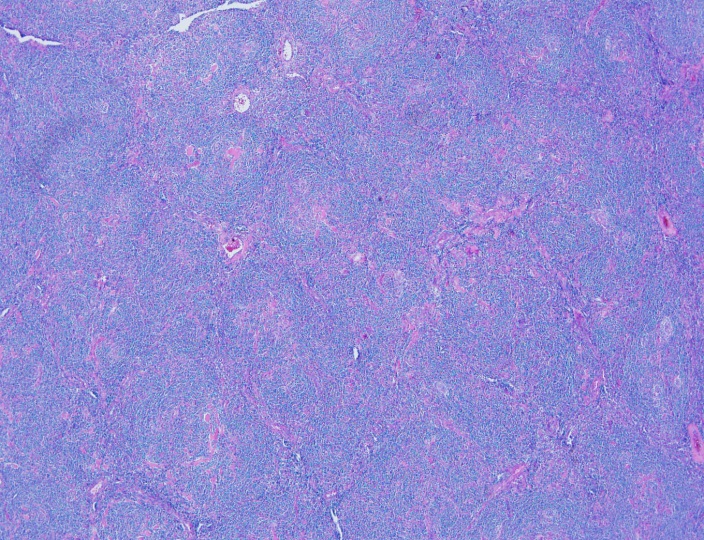

A 45 year old male underwent a chest MRA for aortic dilation due to his history of an aneurysmal aortic root. Upon imaging, an incidental anterior mediastinal mass was seen that measured 4.0 cm. In preparation for an upcoming cardiac surgery, the patient underwent a thymectomy with resection of the mass. The sample is a section from the mediastinal mass.

Diagnosis

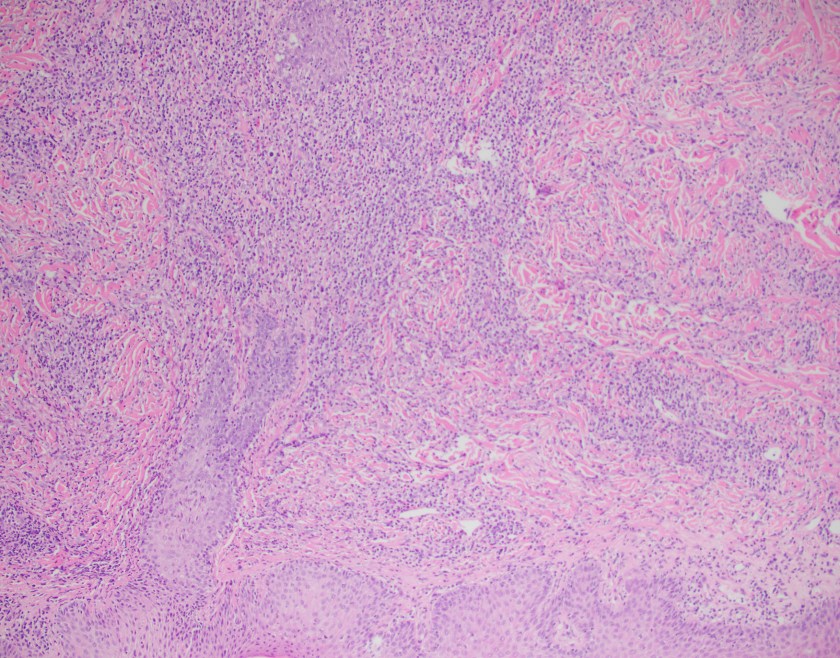

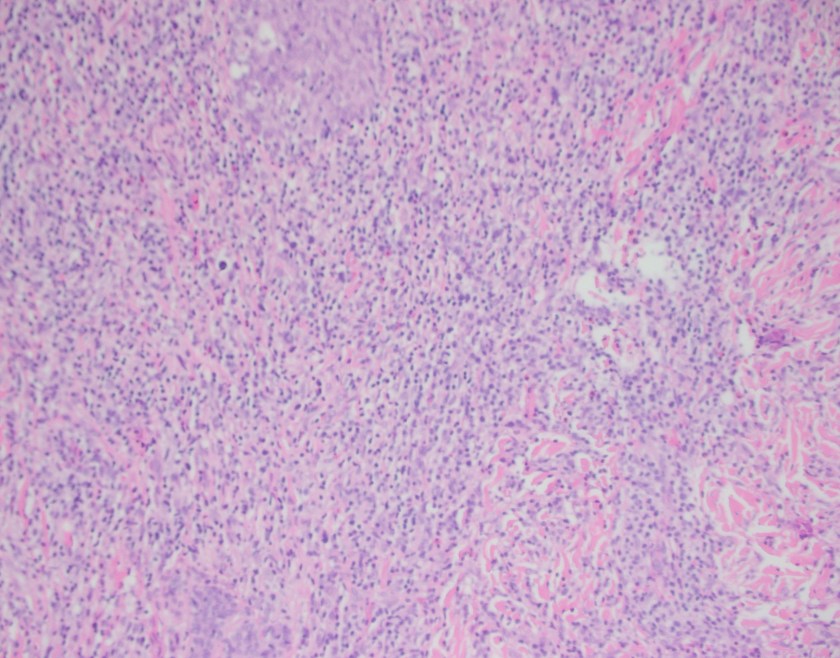

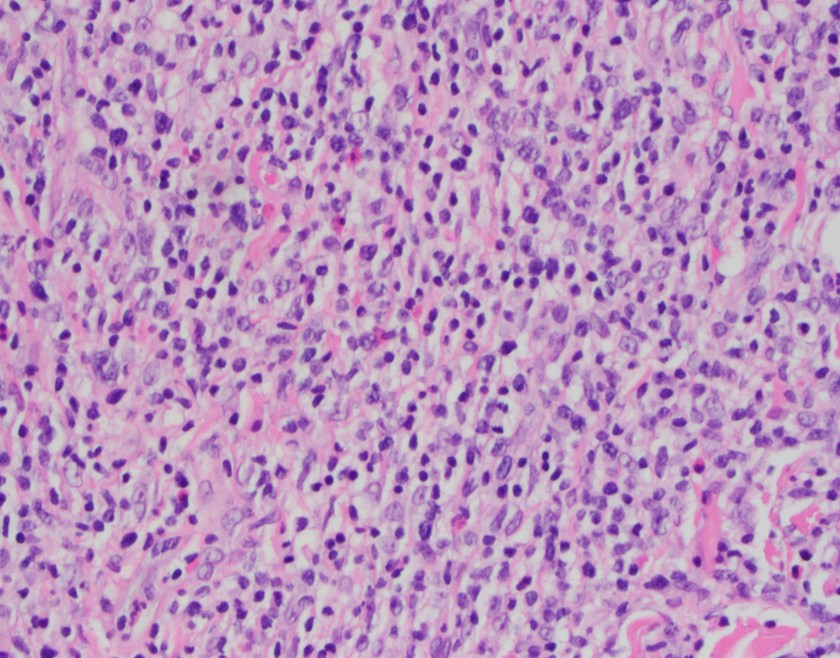

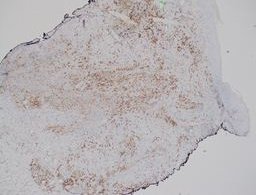

Sections show an enlarged lymph node with several follicles demonstrating atrophic-appearing germinal centers which are primarily composed of follicular dendritic cells. These areas are surrounded by expanded concentrically arranged mantle zones. Focal “twinning” of germinal centers is present. Additionally, prominent centrally placed hyalinized vessels are seen within the atrophic germinal centers giving rise to the “lollipop” appearance.

By immunohistochemistry, CD20 highlights B-cell rich follicles while CD3 and CD5 highlight abundant T-cells in the paracortical areas. CD10 is positive in the germinal centers while BCL2 is negative. CD21 highlights expanded follicular dendritic meshwork. CD138 is positive in a small population of plasma cells and are polytypic by kappa and lambda immunostaining. HHV8 is negative. MIB1 proliferation index is low while appropriately high in the reactive germinal centers.

Overall, taking the histologic and immunophenotypic findings together, the findings are in keeping with Castleman’s disease, hyaline vascular type. The reported clinical and radiographic reports suggest a unicentric variant.

Discussion

Castleman’s disease comes primarily in two varieties: localized or multicentric. The localized type is often classified as the hyaline vascular type (HVCD). Demographically, it’s a disease of young adults but can be found in many ages. The most common sites for involvement are the mediastinal and cervical lymph nodes.

The classic histologic findings of HVCD involve numerous regressed germinal centers with expanded mantle zones and a hypervascular interfollicular region. The germinal centers are predominantly follicular dendritic cells and endothelial cells. The mantle zone gives a concentric appearance, often being likened to an “onion skin” pattern. Blood vessels from the interfollicular area penetrate into the germinal center at right angles, giving rise to another food related identifier, “lollipop” follicles. A useful diagnostic tool is the presence of more than one germinal center within a single mantle zone.

The differential diagnosis of HVCD includes late stage HIV-associated lymphadenopathy, early stages AITL, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and a nonspecific reactive lymphadenopathy. A history of HIV or diagnostic laboratory testing for HIV would exclude the first diagnosis. AITL usually presents histologically as a diffuse process but atypia in T-cells with clear cytoplasm that co-express CD10 and PD-1 outside of the germinal center are invariably present. EBER staining may reveal EBV positive B immunoblasts in early AITL, which would be absent in HVCD. The most challenging differential would include the mantle zone pattern of mantle cell lymphoma. Flow cytometry revealing a monotypic process with co-expression of cyclin D1 on IHC would further clarify the diagnosis.1

Overall, unicentric Castleman’s disease is usually of the hyaline vascular type. Surgical resection is usually curative in these cases with an excellent prognosis.2

References

- Jaffe, ES, Harris, NL, Vardiman, J, Campo, E, Arber, D. Hematopathology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011. 1st ed.

- Ye, B, Gao, SG, Li, W et al. A retrospective study of unicentric and multicentric Castleman’s disease: a report of 52 patients. Med Oncol (2010) 27: 1171.

-Phillip Michaels, MD is a board certified anatomic and clinical pathologist who is a current hematopathology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well as pathology resident education, especially in hematopathology and molecular genetic pathology.

A Serious Aside

As an unscheduled post, I’d like to make a quick side note separate from public health, zika, and medical school. You may have seen a post I wrote last January about the potential stereotypes and stigmas we might face in laboratory medicine. But, just because we as laboratory professionals operate behind-the-scenes most of the time, we’re still healthcare professionals—and clinician burnout can affect any of us.

I recently watched a video of Dr. Zubin Damania, also known as “ZDoggMD,” a primary care physician and founder of Turntable Health in Las Vegas. He’s a brilliant and passionate doctor with great opinions and an even greater creative sense of humor. Among his many parodies, and “rounds” Q&A questions, ZDoggMD recently had a guest on one of his Facebook shows called “Against Medical Advice” to address the serious issue of suicide and depression in medicine. Janae Sharp was the guest on this episode speaking about her husband, John, a physician fresh into his residency who committed suicide. They go on to talk about her life after this tragedy and how if flipped her and their children’s’ lives upside down. Janae’s described John as a father, a writer, a musician, an idealist, who always wanted to become a doctor. My interest was definitely piqued by this—I tend not to miss most of Dr. Damania’s content—and this is something I’ve been hearing more and more about as my path through medical school continues. But, at one point in the interview my heart just stopped: John was a clinical pathologist. Too close to home, for me at least. I was admittedly surprised.

Pathologist’s don’t have that much stress to make depression and suicide part of that life, I thought. But that is a cold hard assumption. Depression affects so many people at large, and when you’re in healthcare it almost seems like a risk factor on top of issues one might be struggling with. Med school is touted as one of the hardest intellectually, physically, and emotionally grueling experiences you could go through—I will personally vouch for Dr. John and Dr. Damania’s statements about how much these experiences push you to your limits. No sleep, no recognition, no support, fear of failure, imposter syndrome, a wealth and breadth of knowledge that makes you feel like you’re drowning—not to mention that if you do ask for help you’re immediately “lesser” for doing so.

Video 1. ZDoggMD interviews Janae Sharp about her tragic loss, her husband John’s suicide, and the rampant problem of depression and burnout in medicine. Against Medical Advice, Dr. Damania.

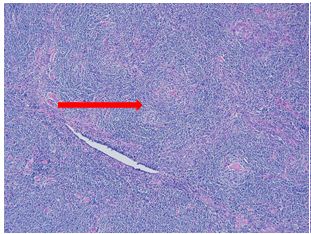

Last month, I was fortunate enough to attend a grand rounds session at my current hospital about this very topic. Presented by Dr. Elisabeth Poorman, internal medicine attending physician, and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School, who talked about how (because of stigmas) medical trainees don’t get the help they need. She demonstrated that prior to med school students are pretty much on-par with their peers with regard to depression. However, once medical school starts, those peers all plummet together as depression rates rise and fall dramatically throughout the various stages of their careers. (I’m just going to go ahead and vouch for this too.) Dr. Poorman shared several case studies that effectively conveyed just how hard it can be when it seems like you are a source of help for many, but no one is there to help you. Story and story recounted the same model of apparent—and often secretive—burnout which ultimately led to a decrease in the quality of care, and in some instances suicide. Dr. Poorman was also brave enough to share her own story. No stranger to depression, herself, it was something that she encountered first hand. She connected herself with this increasingly difficult picture of inadequate support for those of us spending our lives serving others.

There are clear problems facing those of us in healthcare jobs. An ironic consequence, however, of modern scientific advancement is the “doubling time” of medical knowledge. While not necessarily a problem, this refers to the amount, depth, and scope of knowledge physicians and medical scientists are expected to master in order to effectively treat, make critical clinical decisions, and educate our patients. While in 1980 it took 7 years for all medical knowledge to double in volume, it only took 3.5 years in 2010, and in 2020 it’s expected to double every 73 days!1. The problems come as a result of this knowledge because more data means more to do. More time on the computer, higher critical responsibility, and less time to focus on your own mental health all lend themselves to a cyclic trap of burnout. Physicians commit suicide at a rate of 1.5 – 2.3 times higher than the average population.1

Physicians, nurses, clinical scientists, lab techs, administrators, phlebotomists, PCTs—we’re all over worked, under-supported, fall victim to emotional fatigue, and have some of the highest rates for depression, substance abuse, PTSD, and suicide.1 Sometimes, reports from Medscape or other entities will report that burnout is a phenomenon of specialty, hypothesizing that critical nature specialties have more depression than lesser ones2 (the assumption that a trauma surgeon might burn out before a hematopathologist). But truthfully, this is just part of the landscape for all providers. A May 2017 Medscape piece wrote “33% chose professional help, 27% self-care, 14% self-destructive behaviors, 10% nothing, 6% changed jobs, 5% self-prescribed medication, 4% other, 1% pray.”3

So I’m talking about this. To get your attention. So that people reading know they’re not alone. So that people with friends going through something can lend a hand. I’m talking about this. ZDoggMD is talking about this. Jamie Katuna, another prolific medical student advocate, is talking about this. Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is talking about this. This is definitely something we should come together to address and ultimately solve.

What will you do to help?

This was a heavy topic. So in a lighter spirit, I have to share this with all of my laboratory family. If you haven’t heard or seen Dr. Damania’s videos yet, this is the one for you:

Thanks! See you next time!

References

- Poorman, Elisabeth. “The Stigma We Live In: Why medical trainees don’t get the mental health care they need.” Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School. Grand rounds presentation, Feb 2018. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, New York, NY.

- Larkin, Mailynn. “Physician burnout takes a toll on U.S. patients.” Reuters. January 2018. Link: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-physicians-burnout/physician-burnout-takes-a-toll-on-u-s-patients-idUSKBN1F621U

- Wible, Pamela L. “Doctors and Depression: Suffering in Silence.” Medscape. May, 2017. Link: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/879379

–Constantine E. Kanakis MSc, MLS (ASCP)CM graduated from Loyola University Chicago with a BS in Molecular Biology and Bioethics and then Rush University with an MS in Medical Laboratory Science. He is currently a medical student at the American University of the Caribbean and actively involved with local public health.

Hematopathology Case Study: A 69-Year-Old Man Presenting with Marked Thrombocytopenia One Year after Bone Marrow Transplantation

Case history

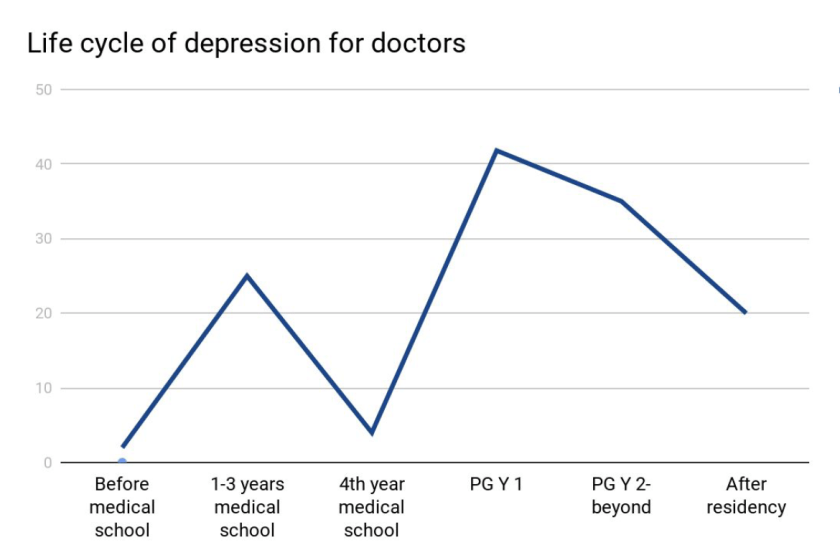

The patient is a 69-year-old man with a history of high-risk MDS (MDS-MLD-RS) diagnosed 1 year prior to his current visit. He was successfully treated with chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. For the next year, several marrow examinations were normal and chimerism analysis revealed >98% donor cells. Currently, he presents with vague symptoms and a CBC demonstrates marked thrombocytopenia of 4K/μL. The low platelet count is initially thought to be related to GVHD; however, a bone marrow examination is performed to assess the status of his disease.

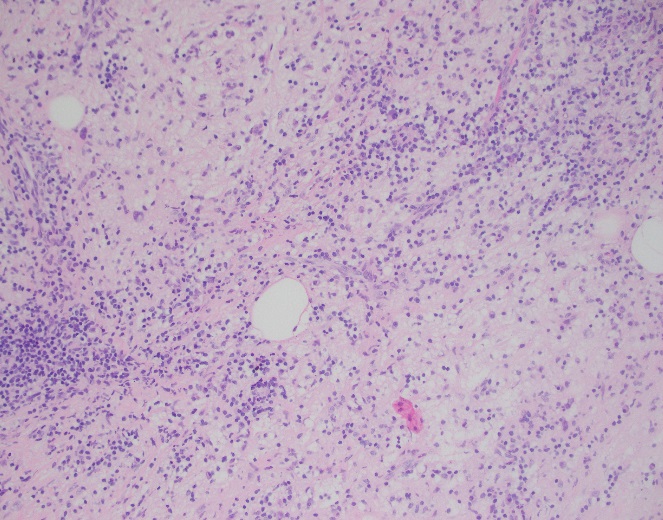

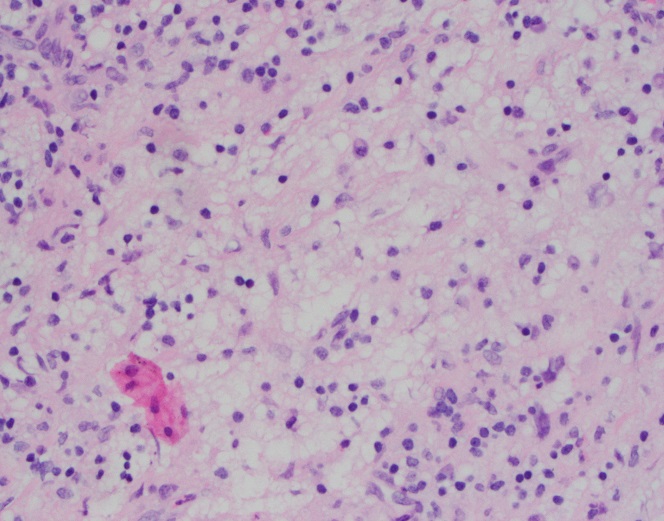

Microscopic Description

Examination of the bone marrow reveals a markedly hypercellular marrow for age with a proliferation of abnormal erythroid cells comprised of sheets of immature and maturing red cell precursors with basophilic cytoplasm. There is a marked increase in larger cells with deeply basophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, dispersed chromatin, perinuclear hoffs, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio consistent with pronormoblasts. These pronormoblasts comprised 31% of a 500-cell cell count. Additionally, the background marrow revealed a total of 81% erythroid precursors with marked morphologic atypia and dyspoiesis. Significant dysmegakaryopoiesis is noted. There is no significant increase in myeloid blasts.

Immunophenotyping

Immunohistochemical staining for E-cadherin, CD61 and CD34 is performed. These stains confirm no increase in CD34 positive blasts. CD61 highlights numerous dyspoietic megakaryocytes with widely separated nuclear lobes. E-cadherin staining is impressive, with over 80% of marrow cellularity shown to be comprised of E-cadherin positive erythroid cells.

Diagnosis

The patient’s history of MDS with current dyspoiesis, presence of >80% immature erythroid precursors with >30% proerythroblasts is diagnostic of Acute Myeloid Leukemia, NOS (Pure Erythroid Leukemia) per 2017 revision of the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms.

While successive chimerism reports thus far had shown >98% donor cells, the chimerism associated with this marrow biopsy reveals a decrease in the percentage of donor cells to 44% confirming the relapsed nature of his myeloid malignancy.

Discussion

Di Guglielmo syndrome, known as M6 leukemia in the FAB classification, was named after Giovanni Di Guglielmo, an Italian hematologist who first characterized the disease in 1917. After a few iterations in different classification schemes, the 2008 WHO Classification characterized two types of ‘erythroleukemia’ the erythroid/myeloid type and the pure erythroid leukemia. The former category of erythroid/myeloid type was removed in the 2017 update of the WHO classification with cases meeting criteria for that diagnosis now falling under the category of MDS. ‘Pure Erythroid Leukemia’ remains, and comes under the AML, NOS category, requiring >80% erythroid progenitors with > 30% proerythroblasts.

An extremely rare leukemia, PEL usually occurs as a progression of previous MDS and very uncommonly as de novo disease. Morphologically, PEL reveals proerythroblasts with deeply basophilic, agranular cytoplasm which is usually vacuolated. Occasionally, smaller ‘blasts’ with scant cytoplasm may resemble lymphoblasts. PEL is an exception to the rule of needing 20% ‘myeloid blasts’ to make an acute leukemia, since often the true myeloblast count is low.

In trephine core biopsies erythroid progenitors may take up an intra sinusoidal growth pattern with a sheet-like arrangement and typically reveal some element of background dysmegakaryocytopoiesis. When PEL lacks specific erythroid differentiation, it may be difficult to differentiate from other types of AML such as Acute Megakaryoblastic Leukemia. Park and colleagues recently categorized some under reported morphologic features of PEL and recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities associated with this disease. These findings included (but were not limited to) a broad morphologic spectrum of erythroblast morphology from undifferentiated blasts to proerythroblasts. They reported bone marrow tumour necrosis in trephine biopsies in over 70% of their cases. Of the cases wherein karyotyping was available, there was a highly complex and monosomal karyotype noted involving the TP53 gene locus.

PEL is associated with an aggressive course with a median survival of 3 months.

References

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016 Jan 1:blood-2016.

- Wang W, Wang SA, Jeffrey Medeiros L, Khoury JD. Pure erythroid leukemia. American journal of hematology. 2017 Mar 1;92(3):292-6.

- Park DC, Ozkaya N, Lovitch SB. Acute leukaemia with a pure erythroid phenotype: under-recognized morphological and cytogenetic signatures associated universally with primary refractory disease and a dismal clinical outcome. Histopathology. 2017 Aug;71(2):316-321. doi: 10.1111/his.13207. Epub 2017 May 5.

-Michael Moravek, MD is a 2nd year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at Loyola University Medical Center. Follow Dr. Moravek on twitter @MoravekMD.

-Kamran M. Mirza, MD PhD is an Assistant Professor of Pathology and Medical Director of Molecular Pathology at Loyola University Medical Center. He was a top 5 honoree in ASCP’s Forty Under 40 2017. Follow Dr. Mirza on twitter @kmirza.

The “C” in HCV Stands for “Curable”

Hi everyone! It has felt so good to find myself back in the throes of hospital life. My time in the classroom during the first half of medical school was great—but this new chapter is what makes medical school very worth it. As with any new hospital, orientation was pretty run-of-the-mill: administrative paperwork, employee/student health clearance, and yet another Mantoux PPD (despite having a current QuantiFERON—lab family, you get me).

However, after all the introductory logistics, I finally reported to my first rotation. It is an elective clerkship in primary care focused primarily on patients with HIV and/or Hepatitis. My familiarity with hospital life made the transition back easy enough as I made my way to the nurses’ station looking for my attending. Being forwarded in the direction I had to go, I knocked on the door and started to introduce myself—but was abruptly interrupted. There were already two fellow student colleagues in that room with my attending and a patient. I was enthusiastically included in the process right away, and it has been non-stop since then. I am told this is a “different” rotation where I’m going to feel lucky to have so much hands-on experience, and so far, I agree. While I reminisce on these past few weeks, it’s not a specific patient or case that has stuck with me, but an overall theme I’ve noticed in this rotation. With heavy utilization of the right test at the right time (I’m sure we’re all familiar with ASCP’s Choosing Wisely campaign) and proper interpretations of lab data, patients’ chronic illnesses are being managed well and even cured.

Essentially, pharmaceuticals have been advancing so well in the last 5-10 years that treatment regimens for chronic diseases like HIV and HCV are now being actively controlled and cured, respectively. Why does this pique my interest enough to share it with all of you? As I try my best each month to provide you a window into the life of a medical lab scientist/medical student, I do so while focusing on the lab details that seem to be present in every aspect of my journey. The cures and treatments I’m currently working with are tied to lab tests like CD4 counts, viral loads, liver and kidney function tests, and many other routine values. Diagnostic criteria for different patients’ stages of hepatic damage are classified using a Child-Pugh (CTP) score from clinical information such as ascites and encephalopathy along with lab data like INR, bilirubin, and albumin. Patients with chronic conditions come back for follow up week in and week out for lab tests that let us as care providers adjust therapy accordingly. The clinic I currently rotate in provides its patients with the most up to date treatment protocols based on current literature. For example, The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) regularly publish their recommendations for patients with Hepatitis C. It’s heavy reading, and anyone who goes through literature on standards of care knows it’s dense, so I’ll leave the link to the most recent guidelines on HCV testing, management, and treatment here (https://www.hcvguidelines.org/sites/default/files/full-guidance-pdf/HCVGuidance_September_21_2017_g.pdf). Actively and accurately incorporating these treatment protocols into the patient care algorithms works and demonstrates great utilization of lab driven data with new available therapies.

As a baseline it is critical to understand that patients with positive HCV antibodies will always test positive; once exposed at any point patients will remain positive. While 20% of patients can clear the infection on their own, the remaining majority develop a chronic HCV infection. There is no vaccine for HCV currently; however, there is potential to cure patients—assuming the lab values are interpreted correctly. So, we’ve established that positive HCV antibodies don’t necessarily provide diagnostic data, so the next logical step is to examine a patient’s HCV viral load. Since 2015, the New York State Department of Health established a mandate and protocol for reflex testing HCV Ab positive patients with HCV RNA viral loads. Read the public letter here (https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/hepatitis_c/docs/reflex_testing_letter.pdf). While it makes logical sense, it’s still taking some time to get off the ground as I have seen patient records of different clinics’ providers ordering repeat HCV Ab testing for in-house confirmation—not the best use of resources or lab data. A clear example here of Choosing Wisely for the appropriate lab test. However, so long as HCV viral load stays undetectable by a validated testing method, patients with chronic HCV are promoted to a status of “cured HCV” and need no further testing or follow-up unless new clinical reasons appear to add testing as needed.

Protocols for treatment are based on things like genotype, cirrhosis, and naïve vs. previously failed treatment; treatment schedules last from 8 weeks up to 24 weeks. So, what does a patient’s first visit for HCV treatment therapy look like? Right away (assuming a positive HCV Ab has been obtained) a Hepatitis C RNA viral load is ordered, along with genotype (older treatments are dependent on genotype due to potential for resistance, while newer treatments are pangenotypic), hepatic fibrosis scans (because cirrhosis status determines length of treatment), PT/INR, CBC, CMP, HIV, RPR/CG and other STI screening, and urine drug testing. New generation therapies allow us to proceed despite any comorbid conditions, while maintaining upwards of 95% or greater cure rates. Coinfected patients with HIV or otherwise compromised immune systems are no longer contraindicated to receive HCV treatment. The only significant contraindication in the standards of care currently is that patients not be terminal (i.e. they must have a general prognosis of greater than 6 months).

Being able to watch these treatment protocols in action is great, but one patient in particular will stay with me beyond this clerkship. We received lab results back for a male in his 60s. It was his final HCV viral load based on his treatment schedule. His chart had a box at the end of his schedule labeled “test for cure” and it had remained non-detectable the whole time through treatment. The staff at this clinic does painstaking follow-up with their patients via telephone with impressive results in patient adherence and treatment success. My task one day was to call this patient and inform him that, unless he needed any medical treatment outside of his annual physical, he no longer needed to come in for therapy or testing—his Hep C was cured. He was extremely delighted to hear this news, and I was happy to give it to him. He had been on therapy for less than a few months but had lived with HCV for years. It was an excellent experience! And even more excellent—being part of the connection between lab tests, clinics, and patients. When I started I was just excited to wear that white coat and go visit the hospital’s lab, but I was pleasantly surprised to see the impact on patients’ treatments. Especially considering using the right test at the right time, and truly making a visible difference with excellent data.

See you next time!

Post script: listen to a new podcast my colleagues and I are in where we discuss clinical stories and pearls of wisdom through medical school. As they relate to my posts here on Lablogatory I’ll include a link—this post will focus more in depth on what I presented here regarding HCV cures and lab data.

–Constantine E. Kanakis MSc, MLS (ASCP)CM graduated from Loyola University Chicago with a BS in Molecular Biology and Bioethics and then Rush University with an MS in Medical Laboratory Science. He is currently a medical student at the American University of the Caribbean and actively involved with local public health.

Hematopathology Case Study: A 42 Year Old Female with Right Breast Mass

Case History

A 42-year-old female presented with a right breast mass at an outside hospital that was concerning for carcinoma. A core needle biopsy was performed of right breast mass and the case was sent for expert consultation.

Diagnosis

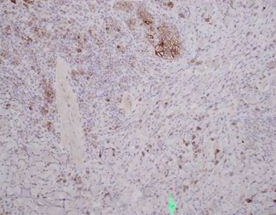

Sections of core needle biopsy material are composed primarily of adipose tissue shows a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with histiocytes being the dominant cell type. Admixed plasma cells are present within the infiltrate. The histiocytes have abundant granular cytoplasm with irregular nuclear contours and some nuclei containing inconspicuous nucleoli. Frequent lymphocytic emperipolesis is identified. Immunohistochemistry performed at the outside facility show positivity for S100 and CD163 within the histiocytes, further highlighting the lymphocytic emperipolesis. Cytokeratin immunostains are negative.

Overall, the morphologic and immunophenotypic findings are consistent with a diagnosis of extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease).

Discussion

Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML) was first described by Rosai and Dorfman in 1969, however, similar findings may be present in extranodal sites thus earning the designation of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD). Although primarily present in lymph nodes, RDD may involve extranodal sites with sinuses and skin being the most frequently affected tissue types. Clinically, RDD often maintains a benign and self-limited course but may undergo exacerbations and recur, requiring surgical management. On histologic examination, RDD involves a rich inflammatory infiltrate with histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. The histiocytes usually display a unique phenotype in which lymphocytes are phagocytosed, a process termed emperipolesis. By immunohistochemistry, these histiocytes are positive for S-100 and histiocytic markers (CD68 and CD163) and are negative for CD1a1.

The largest cohort studied involved 423 cases with 182 having extranodal manifestations2. Chest involvement was first reported by Govender et al. in 1997 in a 34-year-old female3. Overall, RDD is considered rare with a slight male predilection and young African-Americans being the most commonly affected. Sites involved ranging from most common to least common include lymph nodes, skin, upper respiratory tract, and bone4.

Extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, also known as Rosai-Dorfman disease, is a rare pathologic entity that histologically shows a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and emperipolesis, a hallmark of the disease. Although lymph nodes are the most common site of involvement, extranodal sites may be affected and RDD should remain in the differential for lesions that contain abundant histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes as well as the classic feature of emperipolesis.

References

- Komaragiri et al.: Extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease: a rare soft tissue neoplasm masquerading as a sarcoma. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013 11:63.

- Penna Costa AL, Oliveira e Silva N, Motta MP, Athanazio RA, Athanazio DA, Athanazio PRF: Soft tissue Rosai–Dorfman disease of the posterior J Bras Pneumol 2009, 35:717–720.

- Govender D, Chetty R: Inflammatory pseudotumour and Rosai–Dorfman disease of soft tissue: a histological continuum? J Clin Pathol 1997, 50:79–

- Montgomery EA, Meis JM: Rosai–Dorfman disease of soft tissue. Am J Surg Pathol 1992, 16:122–129.

-Phillip Michaels, MD is a board certified anatomic and clinical pathologist who is a current hematopathology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well as pathology resident education, especially in hematopathology and molecular genetic pathology.

When Rapid Blood Culture Identification Results Don’t Correlate, Part 1: Clinical Correlation Needed

More and more laboratories perform rapid (i.e., multiplex PCR) blood culture identification. For the most part, it has been a wonderful addition to the laboratory workflow, not to mention the added benefits of provider satisfaction and improved patient care. Because the PCR only provides the organism identification (sometimes only to the family-level, i.e.; Enterobacteriaceae), laboratories must continue to culture the positive blood for definitive identification and/or antimicrobial susceptibility results. So what do you do when the results don’t correlate?

The Issue

From time to time, the PCR result is not going to correlate with the direct Gram stain or with the culture results. Although this is an issue one would fully anticipate, what do you do when this happens? Do you take some sort of action to arbitrate? Do you report the results as is?

First of all, the PCR assays do not detect all organisms. They only detect the most common bloodstream pathogens. Therefore, one should fully expect to observe cases in which the Gram stain would be positive, but the PCR results would be negative (scenario 1). This is not a surprise.

Additionally, one should also assume that the PCR will occasionally detect organisms that were present at the lower limit of detection of the Gram stain. An example of this would be that the Gram stain is positive for one morphology (i.e.; Gram-positive cocci), but the PCR is positive for two organisms (i.e.; Staphylococcus and a Proteus species). Most of these cases tend to correlate with culture. In other words, although the second organism was not originally observed in the Gram stain, it was detected via PCR and then it also subsequently grew in culture (scenario 2).

Another type of discordant result laboratories sometimes experience is when the organism detected via PCR does not grow in culture for whatever reason. Similar to scenario 2 stated above, except that the culture is also negative for the second organism (scenario 3). Perhaps the patient was treated with antibiotics and the organism is no longer viable for culture? Perhaps a sampling or processing error was to blame?

The Solution

Depending on the scenario and how much work you want to do, you can either repeat testing or try an alternative method. Take scenario 2 for example. If the PCR detects two organisms and the Gram stain is only positive for one, then review of the original Gram stain is warranted. It is possible that the Gram-negative was somehow missed. Our eyes tend to go to the darker, more obvious structures. Perhaps the Gram-negative organism was faintly stained and it was overlooked? It is also possible that the Gram-positive is present in much lower numbers and only Gram-negative organism was originally observed. If the Gram stain result remains the same after review (only one organism observed), then there is nothing much left to do except to wait for the culture. That being said, an alternative method, such as acridine orange can be utilized in this type of scenario (two different cell morphologies). Acridine orange is a fluorescent stain that improves organism detection, as it is more sensitive than the Gram stain (1, 2).

If only the Proteus is growing (and the Staphylococcus isn’t from scenario 2) and we normally subculture positive blood to blood, chocolate, and MacConkey agars, then perhaps including an additional media that inhibits Gram-negative growth would be beneficial.

Scenario 3 can be a little more difficult to solve because you can’t make a non-viable organism grow. It just is what it is. [Spoiler alert: in next month’s blog I plan to write about when you should change your thinking from true-positive to false-positive.]

Regardless of why the result is discrepant, our laboratory appends a comment to the discordant result which says, “Clinical correlation needed.” This lets the clinician know that the results are abnormal and that they must use other relevant information to make a definitive diagnosis. In addition to the comment, we also make sure the discrepancy is notified to laboratory technical leadership (i.e.; Doctoral Director, Technical Lead/Specialist). This allows us to keep track of discrepancies as they may become important to know about in the future (see next month’s blog).

The Conclusion

In terms of organism detection, nucleic assays (i.e., NAATs) can provide superior sensitivity over antigen and culture-based methods of organism detection (i.e., sensitivity = PCR > culture > Gram). From the laboratory perspective, other potential benefits of utilizing nucleic acid detection methodologies include decreased TAT, simplified workflows, and reduced hands-on time. In terms of patient care, many have noted improved outcomes due to increased sensitivity and decreased time to result.

Although advances in technology can significantly improve analytical performance, they can also add complexity to the post-analytical process. Making sense of the results can sometimes lead to confusion. It is important to know the product’s limitations and what your risk(s) is. This should already be known and included in your Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP). Lastly, guiding the clinician to proper result interpretation is also important to maintain valuable patient care.

References

- Mirrett, S., Lauer, B.A., Miller, G.A., Reller, L.B. 1981. Comparison of Acridine Orange, Methylene Blue, and Gram Stains for Blood Cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15(4): 562-566.

- Lauer, B.A., Reller, L.B., and Mirrett, S. 1981. Comparison of Acridine Orange and Gram Stains for Detection of Microorganisms in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Other Clinical Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 14(2): 201-205.

-Raquel Martinez, PhD, D(ABMM), was named an ASCP 40 Under Forty TOP FIVE honoree for 2017. She is one of two System Directors of Clinical and Molecular Microbiology at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania. Her research interests focus on infectious disease diagnostics, specifically rapid molecular technologies for the detection of bloodstream and respiratory virus infections, and antimicrobial resistance, with the overall goal to improve patient outcomes.

Hematopathology Case Study: A 64 Year Old Man with Widespread Lymphadenopathy

Case history

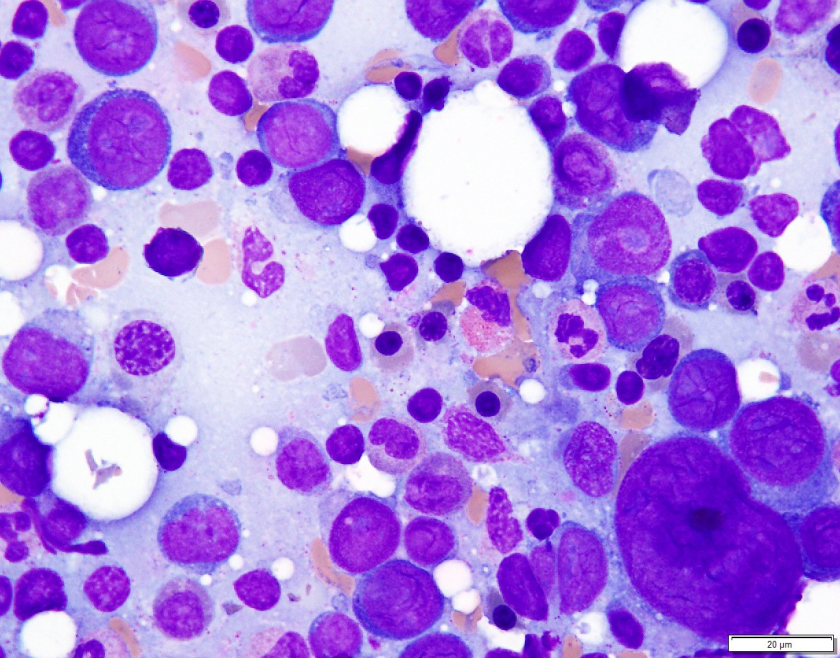

A 64-year-old, previously healthy man presented with a history of cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy of unknown duration. He did not endorse night sweats, weight loss, or fever. Radiologic examination (CT chest and MRI abdomen) revealed numerous enlarged mediastinal, peritracheal, periaortic, periportal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. He underwent excisional biopsy of a 3.5 cm axillary lymph node.

Microscopic Description

Histologic examination of the node revealed distortion of nodal architecture by a proliferation of neoplastic-appearing follicles. Follicles were distinct from one another, and closely packed. In areas the follicles were present back-to-back. Follicular centers were comprised of mostly small, cleaved centrocytes and showed no obvious zonation. There was loss of tingible body macrophages.

Immunophenotyping

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed CD20-positive B cells in a follicular pattern. The germinal centers revealed an underlying follicular dendritic meshwork highlighted by staining for CD21. Interestingly, while the germinal centers demonstrated immunopositivity for BCL-6, there was minimal to absent CD10 staining on follicular B cells. Analysis of BCL-2 staining revealed only few cells to be positive within the follicular centers, consistent with resident follicular helper T cells (Th cells). Equivalent numbers of CD3 and CD5 positive T cells were noted in the interfollicular zones. The Ki-67 proliferation index was estimated at 15-20% within follicular centers. Flow cytometric phenotyping demonstrated a lambda light chain restricted clonal B-cell population expressing CD20, CD19 and, FMC7. These neoplastic B-cells were negative for CD5 and CD10 expression.

Diagnosis

The morphologic features were consistent with Follicular Lymphoma; however the phenotype (BCL-2 negativity in follicular centers) was unusual for this diagnosis. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was negative for an IgH/BCL-2 fusion; however, a BCL-6 rearrangement at the 3q27 locus was detected in 70% of the cells. Taken together, a diagnosis of Follicular Lymphoma with a BCL-6 rearrangement was given.

Discussion

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a germinal center derived B-cell neoplasm. The majority of cases exhibit the pathognomonic translocation t(14; 18)(q32; q21). This translocation leads to overexpression of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein, which can be detected by immunohistochemistry on germinal center B cells. Lymphoma cells are usually positive for germinal center origin markers BCL-6 and CD10 and do not co-express CD5. As exhibited in this case, FL can exhibit biologic heterogeneity and may not express these typical markers. The follicular proliferation with absence of germinal center zonation and tingible body macrophages as seen in this case represents classic morphology of follicular lymphoma but aberrant phenotypic markers [and absence of t(14;18)] may be a pitfall in this diagnosis.

FL with lacking of CD10 expression, BCL-2 expression, and t(14;18) translocation and harboring only BCL-6 positivity with 3q27 rearrangement is rare. Only few such cases have been reported in the literature. Published data reveals that the hallmark t(14;18) translocation is absent in about 10-15% of FL. The majority of these cases are negative for BCL-2 expression, and 9-14% of them demonstrate BCL-6 rearrangement (3q27 locus). While BCL-6 rearrangement can be present in both the usual t(14;18) harboring FL, and also in cases without t(14;18), the latter is rare. Interestingly, studies have shown BCL-6 rearrangements to be more frequent in in BCL-2 rearrangement negative FL – which is evidence of the anti-apoptotic role of non-rearranged BCL-6 in certain microenvironments.

One third of t(14;18) negative FL are also reported to have rare or negative expression of CD10. Morphologically, this subtype has been shown to have significantly larger follicles than their t(14;18)-positive counterparts, but the distinction may not be obvious in all cases. Some of these cases are shown to have a component of monocytoid B cells. This findings can be problematic in differentiating these FL cases from marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) that can also harbor BCL-6 rearrangements and lack t(14;18), CD10 and BCL-2 positivity. Absence of prominent marginal zone proliferation, BCL-6 protein expression and characteristic genetic alterations present in MZL, such as trisomies 3, 7, and 18 can help differentiating MZL from t(14;18)-negative FL.

This case highlights the importance of morphologic evaluation of a excisional biopsy tissue, and FISH studies to help identify the rare t(14;18) negative FL. While the reported cases are few, there is no published difference in prognosis or survival when compared to t(14;18)-positive FL. As such, it is not clear whether the follicular lymphoma grading scheme applies to t(14;18)-negative FL; however, no significant grading difficulties or differences have been reported.

References

- Jardin F, Gaulard P, Buchonnet G, et al. Follicular lymphoma without t(14;18) and with BCL-6 rearrangement: a lymphoma subtype with distinct pathological, molecular and clinical characteristics. Leukemia. 2002;16:2309–2317

2. Leich E, Salaverria I, Bea S, et al. Follicular lymphomas with and without translocation t(14;18) differ in gene expression profiles and genetic alterations. Blood. 2009;114(4):826-834.

–Aadil Ahmed, MD is a 3rd-year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at Loyola University Medical Center. Follow Dr. Ahmed on Twitter @prion87.

-Kamran M. Mirza, MD PhD is an Assistant Professor of Pathology and Medical Director of Molecular Pathology at Loyola University Medical Center. He was a top 5 honoree in ASCP’s Forty Under 40 2017. Follow Dr. Mirza on twitter @kmirza.

Hematopathology Case Study: A 57 Year Old Male with History of Malignant Melanoma

Case History

A 57 year old male with a history of stage IA malignant melanoma presented with a new pink nodule on the right shoulder (see image provided) that has persisted for one month following a tetanus shot. Resultant specimen is a punch biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnosis

Sections show a punch biopsy of skin with a superficial as well as deep dermal infiltration of small and large lymphocytes. No epidermotropism is noted. An admixed background of inflammatory cells including eosinophils, neutrophils, and histiocytes is present.

By immunohistochemistry, CD2, CD4, and CD5 highlight the abundance of lymphocytes indicating a dominant T-cell population. CD30 highlights a major subset of larger lymphocytes that co-express perforin. Granzyme is positive only in a small subset of cells. CD3 is present in a subset of CD30 positive cells indicating downregulation of CD3 in neoplastic cells. By Ki-67, the proliferation index is focally high (70%). CD20 highlights rare B-cells. CD8 is positive in a small fraction of T-cells. EMA is negative.

Overall, the diagnosis is that of a primary cutaneous CD30 positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The differential diagnosis includes lymphomatoid papulosis, type C and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Discussion

Primary cutaneous CD30 positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders are the second most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (30% of cases). The primary groups within this entity include lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) and cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) is composed of larger cells that are anaplastic, pleomorphic, or immunoblastic morphology that express CD30 in over 75% of the tumor cells. C-ALCL most commonly affects the trunk, face, extremities, and buttocks and often present as a solitary or localized nodules or tumors with ulceration. Clinically, the lesions may show partial or complete remission similar to LyP but often relapse in the skin. Interestingly enough, approximately 10% of cases may disseminate to local lymph nodes.

The histologic pattern of C-ALCL demonstrates a non-epidermotropic pattern with cohesive sheets of large CD30 positive T-cells. Ulcerating lesions may show a morphologic pattern similar to LyP with abundant inflammatory cells such as histiocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils with few CD30 positive tumor cells. By immunophenotyping, the tumor cells are CD4 positive with variable loss of CD2, CD5 or CD3 and express cytotoxic markers such as granzyme B, TIA1, and perforin. Unlike systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, C-ALCL does not express EMA or ALK.

The 10 year disease related survival of C-ALCL is 90%. Lymph node status or multifocal lesions does not alter prognosis significantly.

The differential diagnosis also include LyP, type C. These lesions often present on the trunk and extremities and are characterized by popular, papulonecrotic and/or nodular skin lesions. After 3-12 weeks, the skin findings may disappear. Up to 20% of LyP may be preceded by, have concurrent, or followed by another type of lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), C-ALCL, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1

Briefly, there are up to 5 types of LyP (types A-E).2,3 The more recently described LyP type D and E are determined by either simulating an epidermotropic aggressive CD8 positive CTCL and angiocentric and angioinvasive CD8 positive CTCL, respectively.

LyP has an excellent prognosis but since these patients may have other lymphomas, long term follow up is advised.

Overall, C-ALCL and LyP type C show considerable overlap both morphologically and clinically so close clinical follow up is recommended, however both demonstrate an excellent prognosis.

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008.

- Cardosa J, Duhra P, Thway Y, and Calonie E, “Lymphomatoid papulosis type D: a newly described variant easily confused with cutaneous aggressive CD8-positive cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.” Am J Dermatopathol 2012 Oct; 34 (7): 762-765.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Scharer L, et al. “Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas.” Am J Surg Pathol 2013 Jan; 37(1): 1-13.

-Phillip Michaels, MD is a board certified anatomic and clinical pathologist who is a current hematopathology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well as pathology resident education, especially in hematopathology and molecular genetic pathology.

Microbiology Case Study: 6 Year Old Male with Meningitis

Case History

A 6 year old male presented to the emergency department with a concern for ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (VP) malfunction. His past medical history is significant for myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus since birth. On arrival, symptoms included high fever (102.7°F), headaches and swelling at the VP shunt catheter site in the neck. Over the past week, his mother also noted nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. CT scan of the head revealed increased size of the 3rd and lateral ventricles which was concerning for either a VP shunt malfunction or infection. Lab work showed a white count of 13.5 TH/cm2 and elevated CRP values suggestive of an infection/inflammatory process. He was taken to surgery for VP shunt removal and placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD). Intra-operatively, purulent yellow material was noted at both the proximal and distal ends of the catheter. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was sent for Gram stain and bacterial culture. He was started on vancomycin and ceftriaxone.

Laboratory Identification

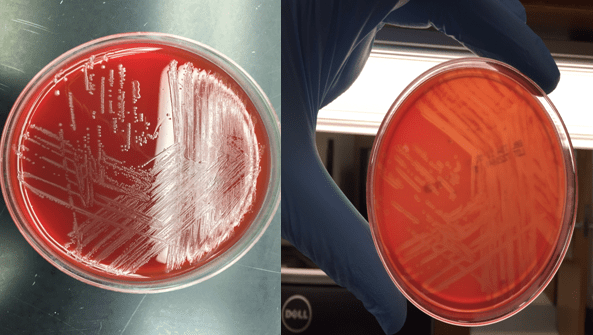

Bacterial cultures collected from a shunt tap and intra-operatively both showed short gram positive bacilli on Gram stain (Image 1&2). The organism grew on blood and chocolate agars as small, gray colonies with a narrow zone of beta-hemolysis when observed closely (Image 3) after incubation at 35°C in CO2. The isolate was positive for catalase and showed a “tumbling motility.” MALDI-TOF MS identified the isolate as Listeria monocytogenes.

Discussion

Listeria species are gram positive bacilli that grow as facultative anaerobes and do not produce endospores. The major human pathogen in the Listeria genus is L. monocytogenes and it is found in soil, stream water, sewage & vegetable matter and may colonize the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals.

The most common mode of transmission is ingestion of contaminated foods, in particular, raw milk, soft cheeses, deli meats and ice cream. L. monocytogenes’ ability to grow at cold temperatures (4°C) permits multiplication in refrigerated foods. In a healthy adult, it causes an influenza like illness and gastroenteritis. Pregnant women are especially susceptible to disease and neonates infected in utero can develop granulomatosis infantiseptica which can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth or premature delivery. Elderly or immunocompromised can present with a febrile illness, bacteremia and meningitis (20-50% mortality).

In the microbiology laboratory, L. monocytogenes is usually identified via blood, CSF or placental bacterial cultures. It grows well on standard agars and after overnight incubation, the small, gray colonies show a narrow zone of beta hemolysis on blood agar. L. monocytogenes is positive for catalase & esculin and the CAMP test demonstrates block like accentuated hemolysis. It has characteristic tumbling motility at room temperature and an umbrella shaped motility pattern in semi-solid agar. Automated methods of identification provide reliable species level differentiation on the majority of current platforms.

Susceptibility testing should be performed on isolates from normally sterile sites. Ampicillin, penicillin, or amoxicillin are given for L. monocytogenes, and gentamicin is often added for its synergistic effect in invasive infections. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and vancomycin can be used in cases of allergy to penicillin. Cephalosporins are not effective for treatment of listeriosis.

In the case of our patient, after L. moncytogenes was identified, his antibiotic therapy was changed to ampicillin and gentamicin. Antibiotics were administered for 3 weeks before the placement of a new VP shunt. On further questioning, his mother revealed his diet consisted heavily of hot dogs and soft cheeses. She was educated on how to prevent subsequent infections prior to discharge.

-Jaspreet Kaur Oberoi, MD, is a Pathology resident at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

-Lisa Stempak, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. She is certified by the American Board of Pathology in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology as well as Medical Microbiology. She is the director of the Microbiology and Serology Laboratories. Her interests include infectious disease histology, process and quality improvement and resident education.