“Damn that q-tip goes in deep!

But it lit up negative so d/c to street

But it was flu, cuz he bounced back again

And now my Press Gayney’s a minus ten…”

Video 1. Another classic excerpt from a favorite: ZDoggMD, singing about this year’s flu season and available testing options on the horizon—because, let’s face it—rapid flu tests aren’t quite cutting it anymore.

Hello again everyone! Back again to talk about a new set of recommendations from last month’s post. This time it’s about influenza. Recommendation: get vaccinated. Thank you. See you next time…

Seriously, as the 2018-2019 flu season dawns upon us, it’s time to talk about vaccines, tests, prevention, and health literacy. I’m sure many of your social media pages are filled with various debates, articles, and fake news stories on one side or another pitting science, pseudo-science, and non-science all against each other for public spectacle. In the lens of laboratory science and medicine at large, I think most if not all of us agree that preventable diseases should be prevented, and if not, at the very least detected accurately, sensitively, and early. Influenza A/B is a prime example of a consistent threat to our health and safety that has wavered responses in various socio-medical circles.

Official communication and guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clearly tells those of us in health-care to embrace a multi-tiered approach to protecting public health regarding the flu. That approach includes vaccination, testing, infection control, anti-viral treatment, and anti-viral prophylaxis. And why such a fuss over the flu? It’s a big deal! Last year, the CDC reported approximately 80,000 deaths associated with influenza as a primary cause. 80,000 deaths! That’s almost 7 times as many that died from H1N1/Swine Flu complications back in 2009, where only 12,000 patients were killed by the virus. And even more so, in the terrifying Ebola epidemic of 2016—in which there was a staggering 1 recorded death in the US—nearly 29,000 people were infected globally and only 11,300 died (despite under-reporting). I’m being dramatic, I know. But it’s important for us to recognize true epidemics when they happen, and even more important for societies like ours to be at the forefront of preventing them from developing any further.

Image 2. I’m not here to talk about the anti-vax elephant in the room. That’s not fair to elephants. But imagine if the CDC reported 44% of flu vaccine misconceptions were addressed!

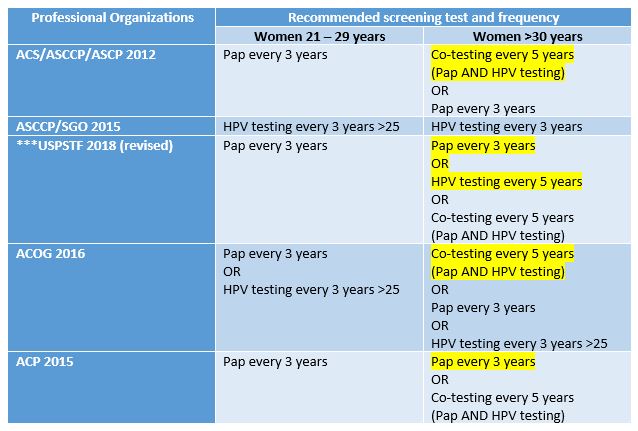

As an aside, I’ll probably recommend that you get your annual flu shot a hundred times in this post alone. But just to have a clear reference, please look at the following table. It’s critical to be able to both distinguish common cold versus influenza symptoms for yourself, as well as educate your patients and peers about the differences between the two. This information can change the way people perceive treatments (i.e. why the doctor only recommended rest/Tylenol and didn’t give out antibiotics for their symptoms) and why it’s absolutely crucial to protect vulnerable populations from an otherwise fatal virus. So, micro-rant aside, it should be clear that by now we should be working on a way to both improve our prophylaxis with vaccines and medications as they always leave room for improvement—I’m looking at you Tamiflu and Relenza! Notwithstanding any analysis of efficacy for the flu vaccine, the CDC reports a variable and transparent success rate of vaccines. It can be difficult to predict and assess epidemiologic trends and mutations as the influenza virus continues to change annually.

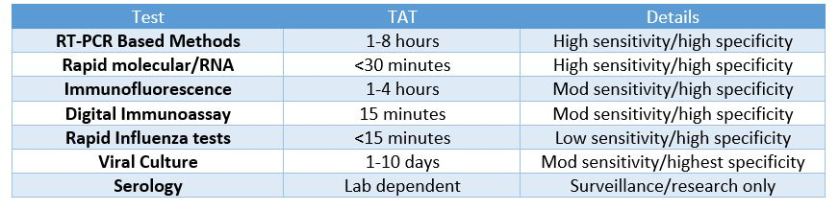

So, what was the deal with ZDoggMD plugging some PCR testing in the opening credits here? That’s a good question and one that inspired this article in the first place. Obviously, if you follow my posts you know I follow his, and at the end of this latest video he discusses new available options for influenza point-of-care testing (POCT) for clinics and emergency rooms. This was a partnership with the company Cepheid and linked with their promoting their POCT PCR-based FluA-B testing. Here’s a quick paraphrasing of the CDC recommendations on influenza testing: because of the numerous false negative tests every season, the bests tests in order of preference are RT-PCR, immunofluorescence, and rapid antigen testing. Did you catch that? Rapid Flu swabs are bottom of the barrel stuff here. UpToDate, the clinical resource for current practices and standards discusses rapid influenza tests as sacrificing turn-around-time (TAT) for accuracy: “commercially available rapid antigen tests for influenza virus yield results in approximately 15 minutes or less but have much lower sensitivity than RT-PCR, rapid molecular assays, and viral culture.” (I didn’t bold those words, they did). Most of the places I’ve worked run through boxes of rapid flu swab kits ALL DAY LONG. But what are we missing? Clinically, this is supposed to be an important “no miss” diagnosis—it’s dangerous, it’s contagious, it’s mutatable…

Who remembers learning biostatistics in school? Remember SPIN and SNOUT? “Specificity is used to rule IN, Sensitivity is used to rule OUT” So why are we relying on the LOWEST sensitivity available to us for ruling out influenza? Probably because of technological/practical limitations up to this point in time, and of course the most glaring limiting reagent of all: funding, also known as “administrative buy-in.” Have I hit enough lab management buzz words in this post? Not yet.

Sweet. So, it’s a little expensive but ultimately better for our patients, right? Done and done, whip up a cost-benefit-ratio report for the suits upstairs and let’s start a validation project! Well, yes and no. I’m a big proponent of utilizing MALDI-TOF—the mass spectrometry based system to replace traditional bacterial identifications. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology stated, “The use of MALDI-TOF MS equated to a net savings of 87.8%, in reagent costs annually compared to traditional methods. …The initial cost of the instrument at our usage level would be offset in about 3 years. MALDI-TOF MS not only represents an innovative technology for the rapid and accurate identification of bacterial and fungal isolates, it also provides a significant cost savings for the laboratory.” What promise! Cepheid’s ED POCT PCR Flu test promises 18% fewer tests needed, 17% fewer antibiotics prescribed, and overall savings per patient visit of up to $700. But this sounds like another, too familiar, recent promise from another voice in our profession. Something about quick, easy, and accurate testing on chips with micro-laboratories available commercially and only using microliters of whole blood for analysis. “Unfortunately, none of those leads has materialized into a transaction. We are now out of time,” read the goodbye letter to the company’s stockholders—Theranos, that’s the one. The moral of the story here: it’s good to remain fiscally prudent when deciding what your clinic or hospital should invest in with regard to testing. However, when something has been a proven and successful replacement which ultimately is recommended by multiple societies within the field then something’s got to give.

What do you see in your practice or laboratory as far as influenza testing? Are there issues I missed? What is your experience with rapid tests, or PCR testing? Is anyone else as big a fan of MALDI-TOF as I am? Did you get your flu shots yet? Leave your comments and questions below! Share with a colleague today!

See you next time!

I have absolutely no affiliation with Cepheid, financial or otherwise, but as an educational/professional resource read more information about Cepheid’s molecular rapid flu tests, read their literature at www.GetTheRightTest.com

References

- Carreyrou J. (2018) Blood Testing Firm Theranos to Dissolve. Wall Street Journal. Health: Theranos Co. Letter to Shareholders. Accessed at: http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/Theranos_Stockholders_Letter_2018.pdf?mod=article_inline

- Cephid (2018) Is it really flu? Cutting emergency department costs with bedside rapid molecular tests. Accessed at: http://www.cepheid.com/images/Cepheid-WP-ED-Cost-FINAL.pdf

- CDC (2017) Interim guidance for influenza outbreak—management in long-term care faciltites. e Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2016-17 Season. Accessed at: http://cepheid.com/images/CDC-interim-guidance-outbreak-management.pdf

- CDC (2018) Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness, 2004-2008. Accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm

- CDC (2018) Flu Symptoms and Complications. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/consumer/symptoms.htm

- Dayhoff-Brannigan, M (2018) To Tamiflu or Not to Tamilflu? National Center for Health Research. Accessed at: http://www.center4research.org/tamiflu-not-tamiflu/

- Dolin, R. (2018) Diagnosis of Seasonal Influenza in Adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-seasonal-influenza-in-adults?search=influenza&source=search_result&selectedTitle=6~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=6#H1289544319

- McNeil, D. (2015). “Over 80,000 Americans Died of Flu Last Winter, Highest Toll in Years” The New York Times.

- McNeil, D. (2015). “Fewer Ebola cases go unreported than thought, study finds”. The New York Times

- ZDoggMD (2018) This Flu Test https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKTYw-7ikJQ#action=share

- Tran A, et al. (2015) Cost Savings Realized by Implementation of Routine Microbiological Identification by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. DOI:1128/JCM.00833-15

–Constantine E. Kanakis MSc, MLS (ASCP)CM graduated from Loyola University Chicago with a BS in Molecular Biology and Bioethics and then Rush University with an MS in Medical Laboratory Science. He is currently a medical student actively involved in public health and laboratory medicine, conducting clinicals at Bronx-Care Hospital Center in New York City.