Case History

A 29 year old G2P1 woman presented in labor at 39+2 weeks gestational age. Her pregnancy had been previously uncomplicated. Prenatal infectious disease testing showed that she was negative for HIV and Hepatitis C, but that she was positive for Group B Streptococcus. No test results were available for rubella, VZV, toxoplasmosis, or syphilis.

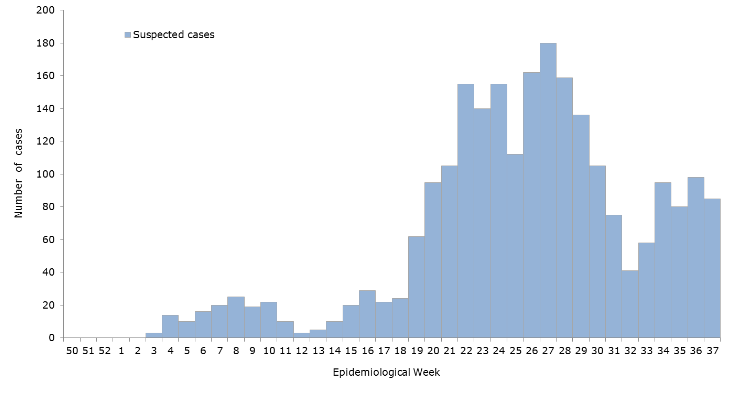

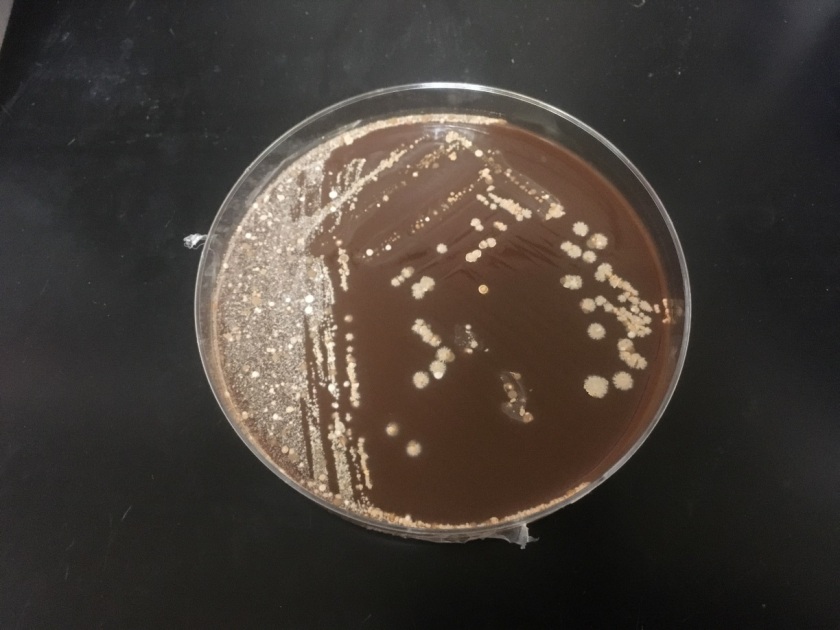

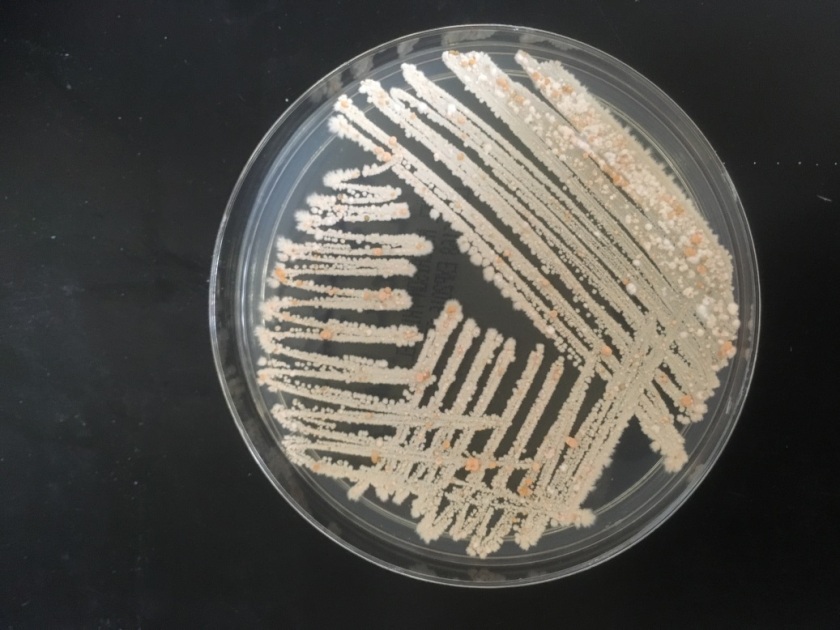

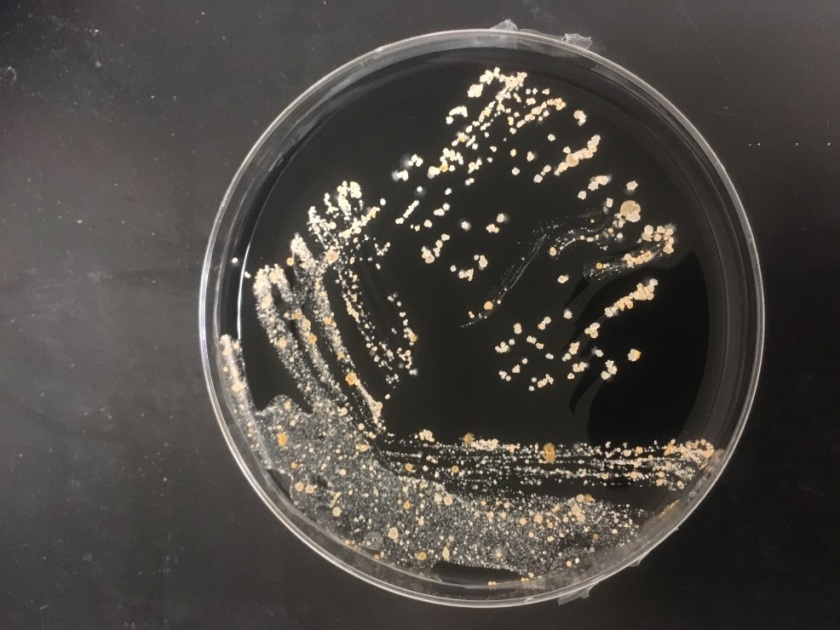

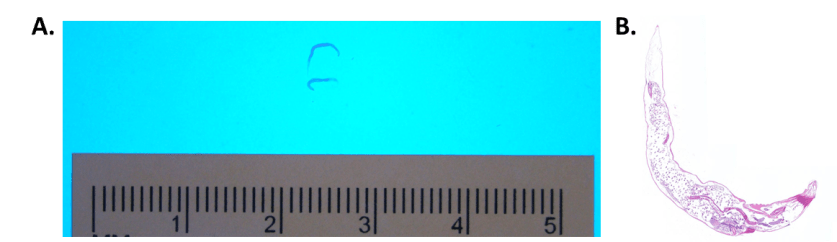

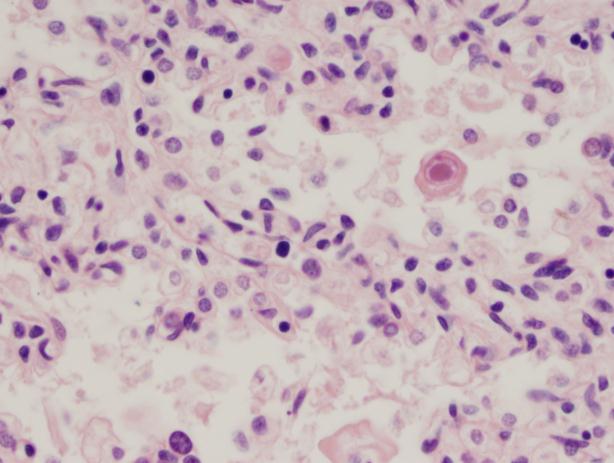

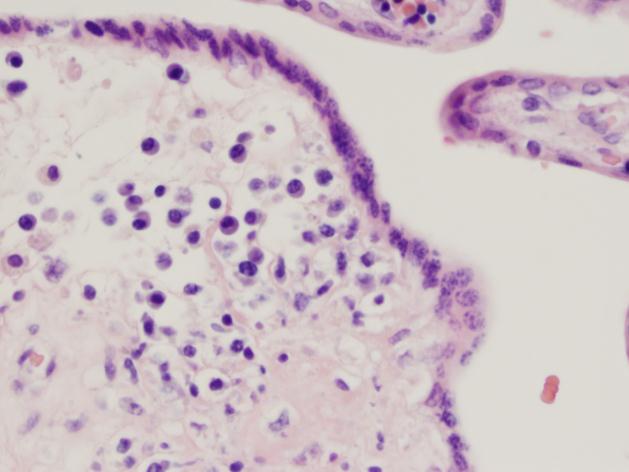

A term male infant was born shortly afterwards by spontaneous vaginal delivery; the mother received less than 4 hours of antibiotics. The baby was noted to be covered in petechiae, and in a moderate amount of respiratory distress. A CBC showed thrombocytopenia to 23 K/cmm. The baby was transported emergently to the neonatal intensive care unit, where platelet transfusions were given. Blood cultures were drawn. The baby was started empirically on ampicillin/gentamycin, and the following day, once platelet counts were improved, a lumbar puncture was performed. The cell counts in the CSF were unremarkable. A cranial ultrasound showed scattered bilateral parenchymal calcifications, mineralized vasculature of the lenticulostriate arteries, and a subependymal cyst. Urine PCR testing was positive for CMV.

Laboratory Work-up

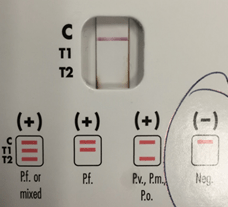

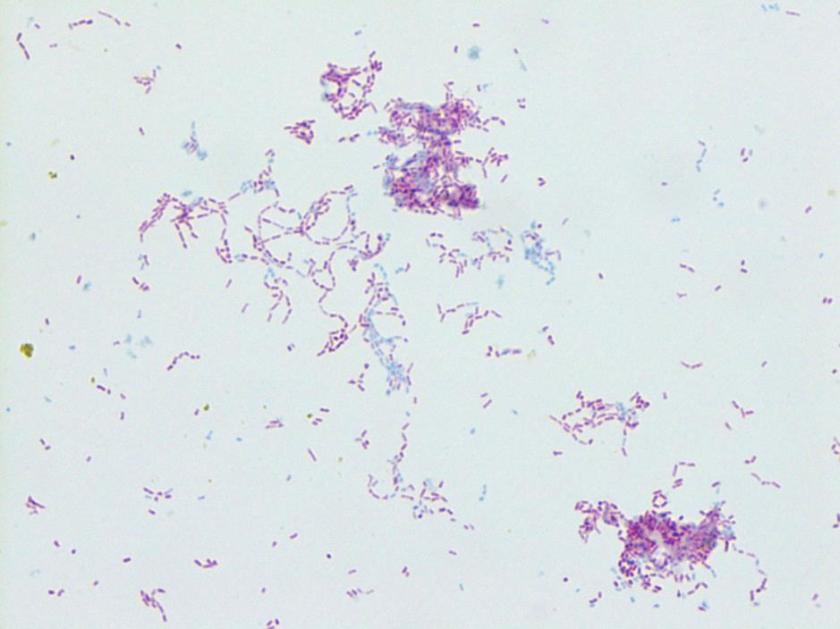

- Bacterial Culture and Smear, CSF: No neutrophils, no bacteria. No growth.

- CSF Viral PCR: Negative for HSV and VZV.

- Urine CMV PCR: Positive.

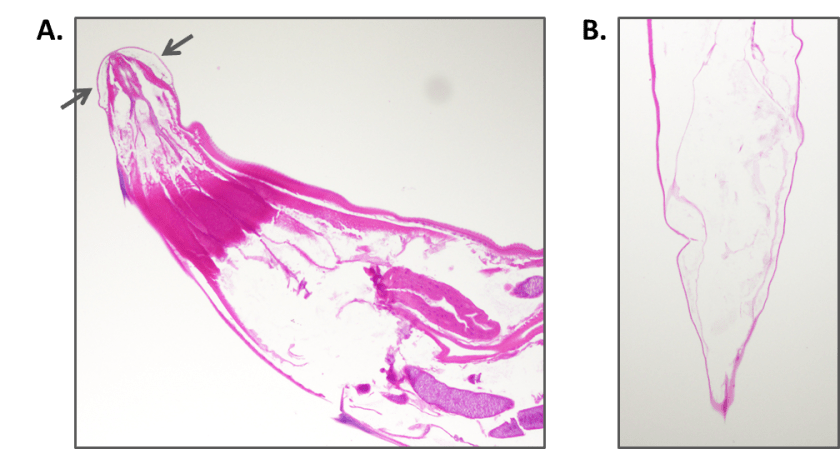

- The placenta was not sent for pathologic examination.

Cranial ultrasound demonstrating scattered parenchymal calcifications.

Discussion

Cytomegalovirus is one of the classic “TORCH” infections. TORCH is an acronym for a group of pathogens that can cause in-utero or intrapartum infections:

- T= Toxoplasmosis

- O= other (syphilis, VZV, parvovirus)

- R= rubella

- C= CMV

- H= HSV

Although these infections share several common signs and symptoms, there are clinically suggestive findings that can help target testing. The combination of thrombocytopenia and intracranial calcifications in this infant raised strong suspicion for congenital CMV. CMV is a member of the herpesvirus family. It is a double-stranded DNA virus with both a viral capsid and envelope. While most babies born with congenital CMV are asymptomatic (~90%), congenital CMV infection is the main etiology of non-hereditary sensorineural hearing loss. This occurs in up to 50% of symptomatic infants and in 10-15% of asymptomatic infants. Symptomatic infants may be small for gestational age, and can be afflicted by thrombocytopenia, petechiae, intracranial calcifications, chorioretinitis, hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, and jaundice. While toxoplasmosis can also cause intracranial calcifications, it does not typically cause thrombocytopenia. Congenital HSV can cause thrombocytopenia, but is not associated with intracranial calcifications.

CMV infection during pregnancy is most often acquired by contact with young children. CMV has the ability to remain latent in the host, and become reactivated at a later time, so pregnancies can be affected by either primary infection or by reactivation of the virus. The risk of vertical transmission is much higher with primary CMV infection (32%) than with recurrent infection (1.4%). Although the rate of vertical transmission increases if the infection occurs later in pregnancy, infections acquired in early pregnancy are more likely to cause symptomatic disease. Treatment for the baby is generally supportive, with antivirals generally used only in symptomatic disease (their utility in asymptomatic infection is debated).

An audiology screen and ophthalmologic exam were both normal in the infant presented here. Oral valgancyclovir was started in addition to other supportive measures.

-Alison Krywanczyk, MD is a 3rd year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

-Christi Wojewoda, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and an Assistant Professor at the University of Vermont.