Sepsis is a medical emergency and a global public health concern. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign started in 2012 and has since issued International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. These Guidelines have been updated several times, and the 4th edition of the 2016 guideline have been issued. The Guidelines are written from the perspective of developed (“resource-rich”) countries, where critical care settings are equipped with tools for managing these patients. Yet, the developing world carries the greatest burden of sepsis-related mortality. Unfortunately, the developing world lacks access to many of the necessary tools for managing the critically ill patient – including basic laboratory testing.

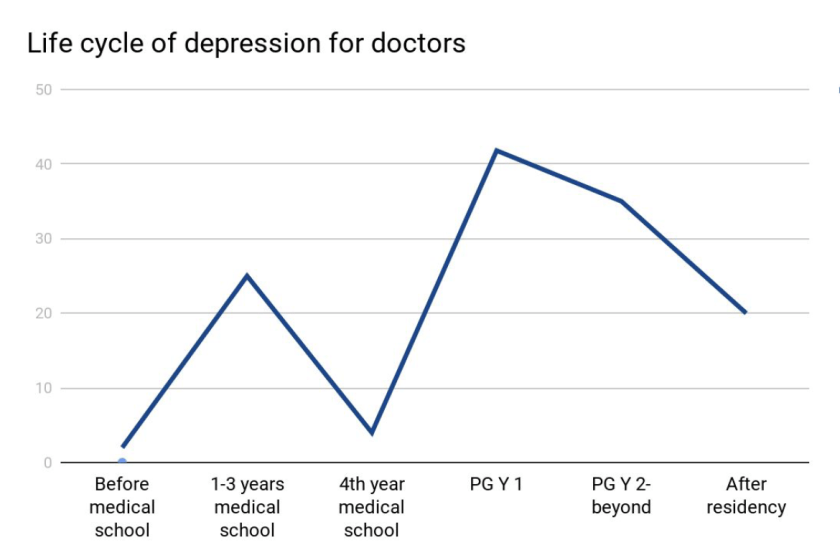

Laboratory values are a significant part of the management of the septic patient. Take a look at the sepsis screening tool. Analytes and lab tests included in screening patients for sepsis include: lactate, creatinine, bilirubin, INR, and blood gases. The Surviving Sepsis bundles require a lactate concentration within 3 hours of presentation, and a subsequent lactate within 6 hours. The care bundle also requires a blood culture within 3 hours of presentation and prior to administration of antibiotics. Early-goal directed therapy for sepsis requires administration of crystalloid based on lactate concentrations. Basics of laboratories in the US, lactate and blood cultures are both difficult to obtain and far from routine in the resource-poor care settings.

Blood gases and lactate are particularly difficult to find and to maintain in the developing world. While there are a number of point-of-care or small benchtop devices – like the iStat (Abbott), the Piccolo (Abaxis), and the Stat Profile pHOx (Nova), it is often cost-prohibitive to maintain these devices. The iStat and the Piccolo are examples of cartridge-based devices. All of the chemistry takes place in single-use cartridges and the device itself is basically a timer. In my experience, cartridge based devices hold up in environmental extremes better than open reagent systems. However, they are not cheap and this can be prohibitive. Cost of a single cartridge can range from $3-10 USD. In countries where patients and their families are expected to pay upfront or as they go for even inpatient medical care, and the income for a family is $2USD/day, routine monitoring of blood gases and lactate by cartridge is just not feasible. Reagent based devices like the Stat Profile use cartons of reagent for many uses. This is much cheaper – if all the reagent is used before it expires! Some healthcare settings can accommodate only 1-3 critical patients, and might not be able to use a whole carton before the expiry, even when adhering to Surviving Sepsis guidelines.

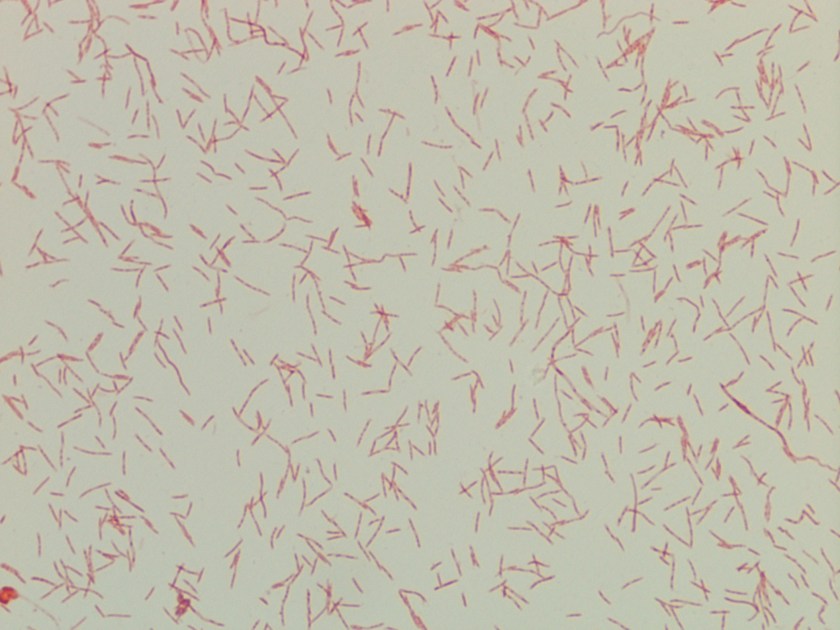

Blood cultures and subsequent treatment with appropriate antibiotics is a large part of the surviving sepsis campaign. Microbiology in the developing world is often limited to a few reference laboratories in country. Also, the number of potential infectious agents is larger in the developing world where diseases like malaria and dengue fever are common. Multiplexed nucleic acid tests might fill the gap here. Again, the cost is a major factor. Just reagents alone for a single multiplexed NAT can be over $250 USD.

In short, if the surviving sepsis guidelines really do help decrease sepsis mortality, the developing world doesn’t have a chance unless it has a greater laboratory capacity. Basic labs that we don’t think twice about can be very hard to come by in resource-poor environments. The tests already exist in forms that can be used in resource-poor settings – they just need to be cheaper, at least for those in limited resource settings. Are you listening, Abbott?

–Sarah Riley, PhD, DABCC, is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Pathology and Immunology at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine. She is passionate about bringing the lab out of the basement and into the forefront of global health.