When we think about infectious disease (ID) and specific syndromes (culture-negative endocarditis, for example), it can be difficult to know the etiology.1 This is because different microorganisms can cause similar symptoms and depending on the specimen submitted to the laboratory for testing, you may need to split your specimen. It may be that the infection is localized to a small area (valve vegetation) and all you get for processing is a small volume of tissue. Another scenario is that you get a sufficient amount of specimen, but you must split the specimen for culture, multiple send out studies, pathology, etc. Or even worse–a small volume specimen that you need to split for multiple diagnostic tests.

We recently had a case of endocarditis. The patient’s blood cultures were negative, and she was going to have her mitral valve replaced. The ID team requested that we send the tissue for broad-range bacterial and fungal sequencing. We can do that- not a problem.

The Issue

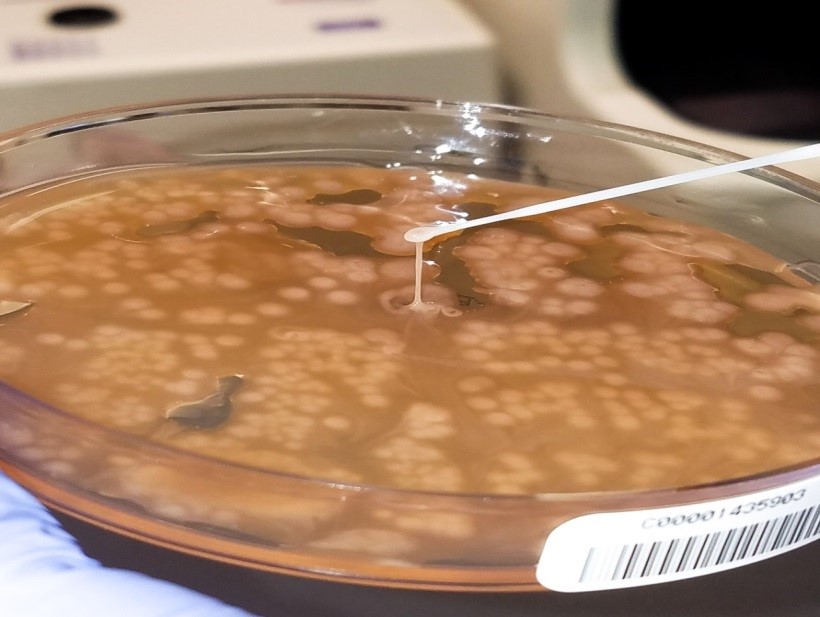

As requested, the specimen (mitral valve vegetation) was split once it was received in the laboratory. Half went into the freezer for sequencing requests which we send to a reference laboratory and the other half was processed for bacterial (including mycobacteria) and fungal cultures.

In our experience, if no organisms are observed, then no DNA is detected. Therefore, it is not beneficial to send tissue for sequencing if we do not observe an organism (or something that looks suspicious for an organism) to begin with. In parts 2 and 3 of this series we will go into greater detail of the workflow for examining tissue for infection, but for now we will focus on the processing piece.

No organisms were observed in the direct smears (Gram, fungal, and acid-fast) and all cultures were negative. Because no organisms were observed, we did not send the tissue for sequencing. However, the patient was not improving and ID insisted that we send the tissue for sequencing anyway. As a last ditch effort we decided to homogenize the frozen tissue to see if by chance organism was present.

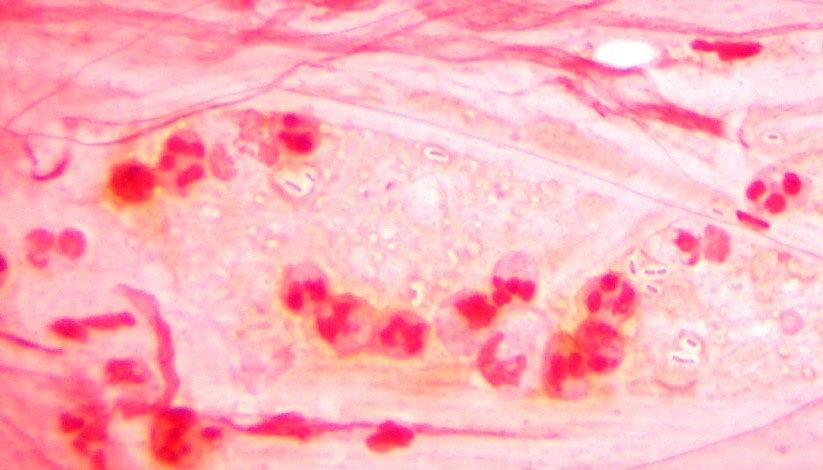

Long story short: the Gram stain did not reveal organism, but acridine orange2 did. We cultured the tissue and recovered an organism. Moral of the story: specimen processing can be tricky. It is an inherent issue that we must be aware of. How were we to know in which part of the tissue the organisms were? By definition, this is sampling error at its finest.

The Solution

Moving forward, rather than split the specimen prior to processing we have changed our protocol to homogenize the tissue first, then split the specimen. We believe this will eliminate similar scenarios from happening again in the future.

The Conclusion

All specimens are different in their composition. Unlike body fluids, which are easy to vortex and make homogeneous; tissue is more complex. Whatever the specimen, make sure your protocol(s) reduces sampling error.

References

- Subedi S, Jennings Z, Chen SC. 2017. Laboratory Approach to the Diagnosis of Culture-Negative Infective Endocarditis. Heart Lung Circ. 26(8):763-771.

- Lauer BA, Reller LB, Mirrett S. 1981. Comparison of acridine orange and Gram stains for detection of microorganisms in cerebrospinal fluid and other clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol.14(2):201-5.

-Raquel Martinez, PhD, D(ABMM), was named an ASCP 40 Under Forty TOP FIVE honoree for 2017. She is one of two System Directors of Clinical and Molecular Microbiology at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania. Her research interests focus on infectious disease diagnostics, specifically rapid molecular technologies for the detection of bloodstream and respiratory virus infections, and antimicrobial resistance, with the overall goal to improve patient outcomes.