ABO and H are the most important of the currently characterized blood group systems, since incompatibility between transfused red cells and recipient plasma leads to potentially devastating consequences. Those learning about this system spend lots of time memorizing biochemical details that can be overwhelming. In addition, exam-writers seem to enjoy asking questions about unusual entities in these systems that most blood bankers will never see in real life. Two very rare situations with altered red blood cell appearances (“phenotypes”), known as “Acquired B” and “Bombay,” are among those most frequently discussed on examinations. In a previous post, I discussed the Acquired B Phenotype (see my web page for further details and a video presentation). Today, let’s proceed with details about the very famous Bombay Phenotype.

In the 1950’s, a small group of people were identified in an area in India surrounding the city of Bombay (now called “Mumbai”) that appeared to be blood group O at first glance. As you should know from a basic understanding of the ABO system, group O individuals have antibodies against both A and B antigens, and as a result, can only receive red blood cells from donors who are also group O. The patients reported by Bhende et al (Lancet 1952;1:903-4), however, carried an extra antibody in their plasma that made them INCOMPATIBLE with others that were truly blood group O. These individuals (and others described since) lack a precursor antigen known as “H” both on their RBCs as well as in their secretions and plasma.

In brief, ABO antigens on red blood cells are made in a sequential manner. First, long sugar chains attached to either lipids or proteins (glycolipids or glycoproteins, respectively) on the surface of the RBC must be modified through the work of an enzyme encoded by the H (FUT1) gene (chromosome 19) to display H antigen activity. Only then can the chain be further modified by the action of a second enzyme that adds a single sugar to change that H antigen into either an A or a B antigen. The alleles inherited at the ABO gene site on chromosome 9 (A, B, and/or O) determine which ABO antigens will be expressed on the red cell surface, but again, such a change ONLY happens if the precursor antigen (H) is made first.

ABO antigens are unusual in that they are not only attached to RBCs, but are also present in free-floating forms throughout the body. The same manufacturing principle (first make H, then make A or B) applies to the formation of soluble ABO antigens found in virtually all bodily fluids, including plasma and saliva (and other secretions). The enzyme that is responsible for H antigen formation in these fluids is different than the one described above; it is encoded by the Se (FUT2) gene (also on chromosome 19).

If a person lacks both active forms of both the H (FUT1) and Se (FUT2) alleles (described as having the genotype hh, sese), they are incapable of making H antigen either in secretions and plasma AND on the surface of the RBC (they are described as “H-deficient non-secretors”, and commonly with the shorthand Oh). The genetic mechanism of these changes is well described in the original cohort in India (a particular single nucleotide polymorphism in FUT1 accompanied by a total deletion of FUT2), and multiple additional mutations have been identified that could lead to someone lacking active forms of both alleles.

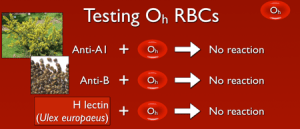

So, with that out of the way, what does this mean? Well, if a person lacks the ability to make H antigen in both RBC-based and free precursor chains, they will appear to be blood group O, just like someone who inherits two O alleles at the ABO site. However, unlike group O RBCs, which carry more H antigen than any other ABO group, H-deficient non-secretor RBCs have NO H antigen (this can be demonstrated easily in blood banks by showing no reaction when the RBCs are mixed with the H lectin Ulex europaeus). In keeping with the way other ABO system antibodies are formed, Bombay individuals make anti-A, anti-B, and anti-A,B, exactly like others that are group O. However, they also make a strong and very dangerous anti-H. The antibody is primarily IgM, but like most ABO-related antibodies, it reacts strongly at body temperatures, and generally is considered highly capable of giving rise to dangerous hemolytic transfusion reactions. As a result, Bombay patients can really receive blood only from others who completely lack the H antigen (which functionally means they should either get their own blood that has been stored for their future use or blood from another H-deficient non-secretor).

There are variants of Bombay, most notably the “Para-Bombay” phenotype in which the patient is H-deficient on RBCs, but IS capable of making ABO antibodies in secretions and plasma (these patients are H-deficient secretors). The key fact that must be evaluated in all of the Bombay-related phenotypes is whether or not an anti-H has been formed that is capable of reacting at body temperature. If so, Bombay variants must also receive only H-deficient red blood cells.

As mentioned, most workers will never see a patient with the Bombay Phenotype. This entity is seen mostly in examination world, but it is nonetheless very important for transfusion service personnel to be aware of this rare phenotype and prepared to take steps to diagnose it. I have seen reports of Bombay cases misdiagnosed as non-ABO high-frequency alloantibodies, and am aware of a case where the diagnosis became apparent when a child was born with an ABO type that seemed impossible based on the ABO types of the parents.

-Joe Chaffin, MD, is the new Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for LifeStream, a Southern California blood center headquartered in San Bernardino, CA. He has a long history of innovative educational efforts and is most widely known as the founder and chief author of “The Blood Bank Guy” website (www.bbguy.org).