Case History

The infectious disease service was consulted on an 83 year old male for fever.

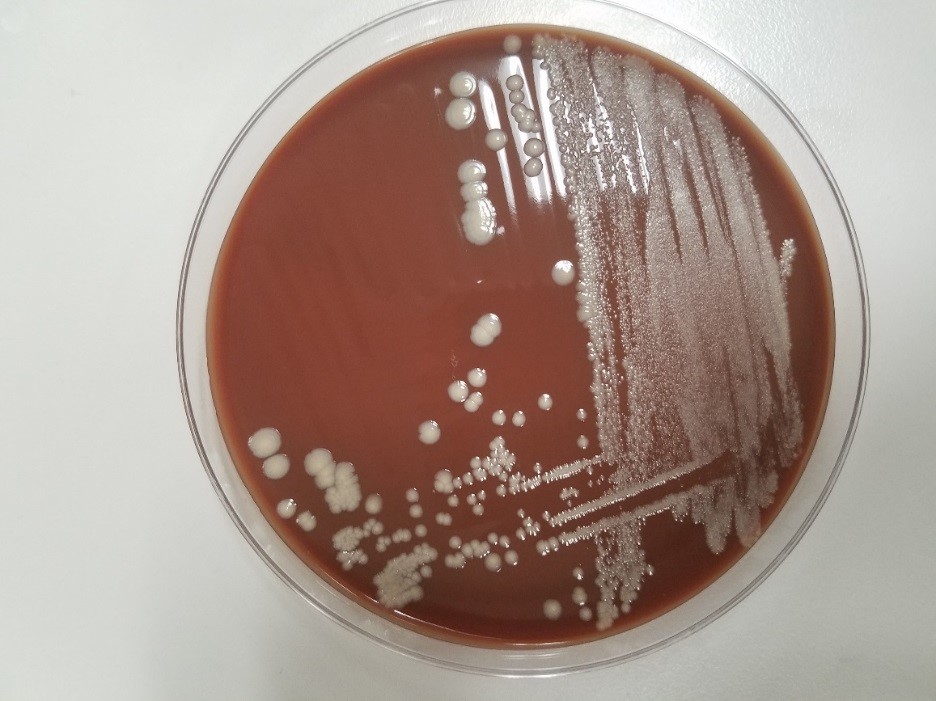

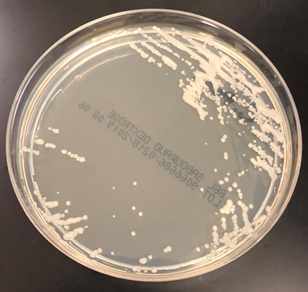

His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus, anemia and renal insufficiency. He initially presented 3 weeks ago with chills, rigors and fever to 103 degrees Fahrenheit. For the past several months, the patient has had weight loss (10-20 pounds over an unspecified timeframe), fatigue and new iron deficiency anemia. A heart murmur was heard on physical exam. The patient was admitted for suspicion of sepsis and he was started on empiric antibiotics vancomycin and ceftriaxone. Three sets of blood cultures were drawn prior to initiation of antibiotics, which were all positive for gram positive cocci in pairs and chains. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). TEE showed large vegetation on posterior mitral leaflet measuring 1cm x 1.8 cm, and a smaller mass on the anterior leaflet. A week after admission, a mitral valve replacement was performed followed and a portion of the valve was sent for culture (Figure 1).

Laboratory Identification

Discussion

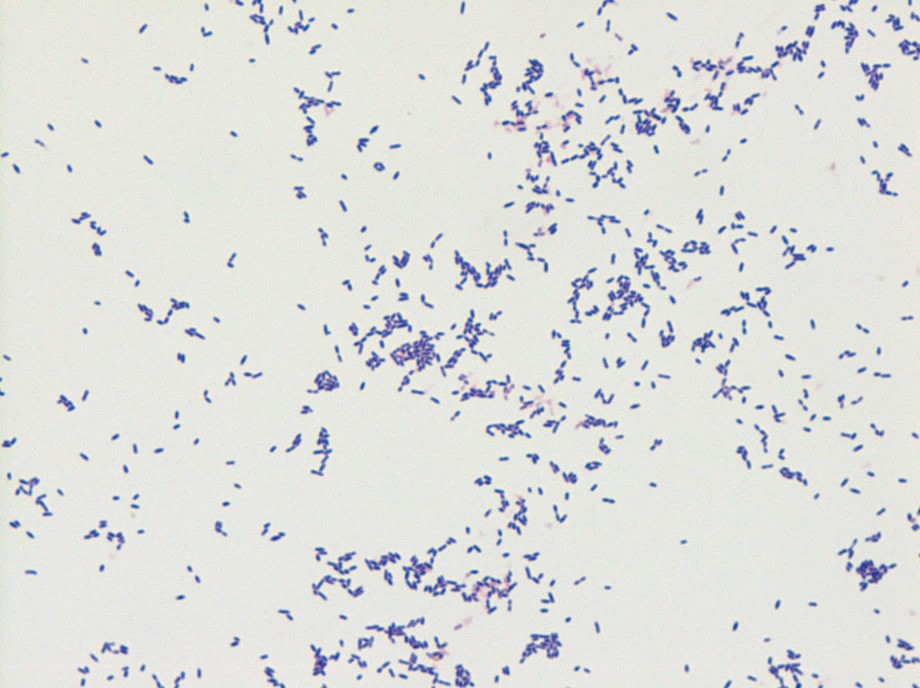

The gram positive organism from blood and mitral valve culture was identified as Streptococcus mitis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. S. mitis is a member of the Streptococcus genus. Streptococci have a number of features that aid in laboratory identification: they are Gram positive, catalase-negative, spherical/ovoid, with organisms that are usually found in chains. They are facultative anaerobes.

More specifically, S. mitis belongs to the viridans streptococci group which includes Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguis, and Streptococcus salivarius, among many others. The most common infection caused by viridans streptococci is bacterial endocarditis, as in the case of this patient. Other infections can include brain abscesses, liver abscesses, dental caries, and bacteremia.

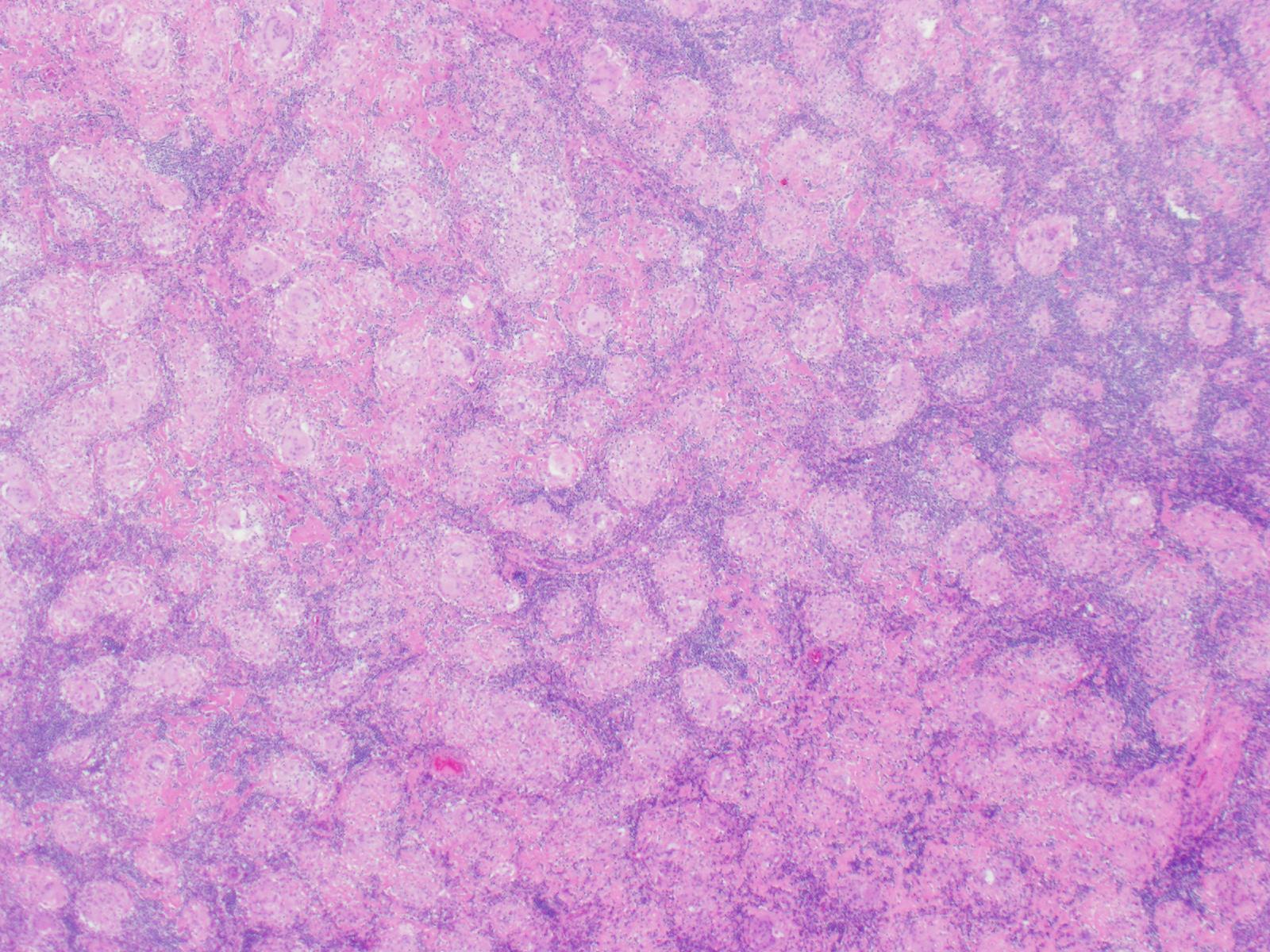

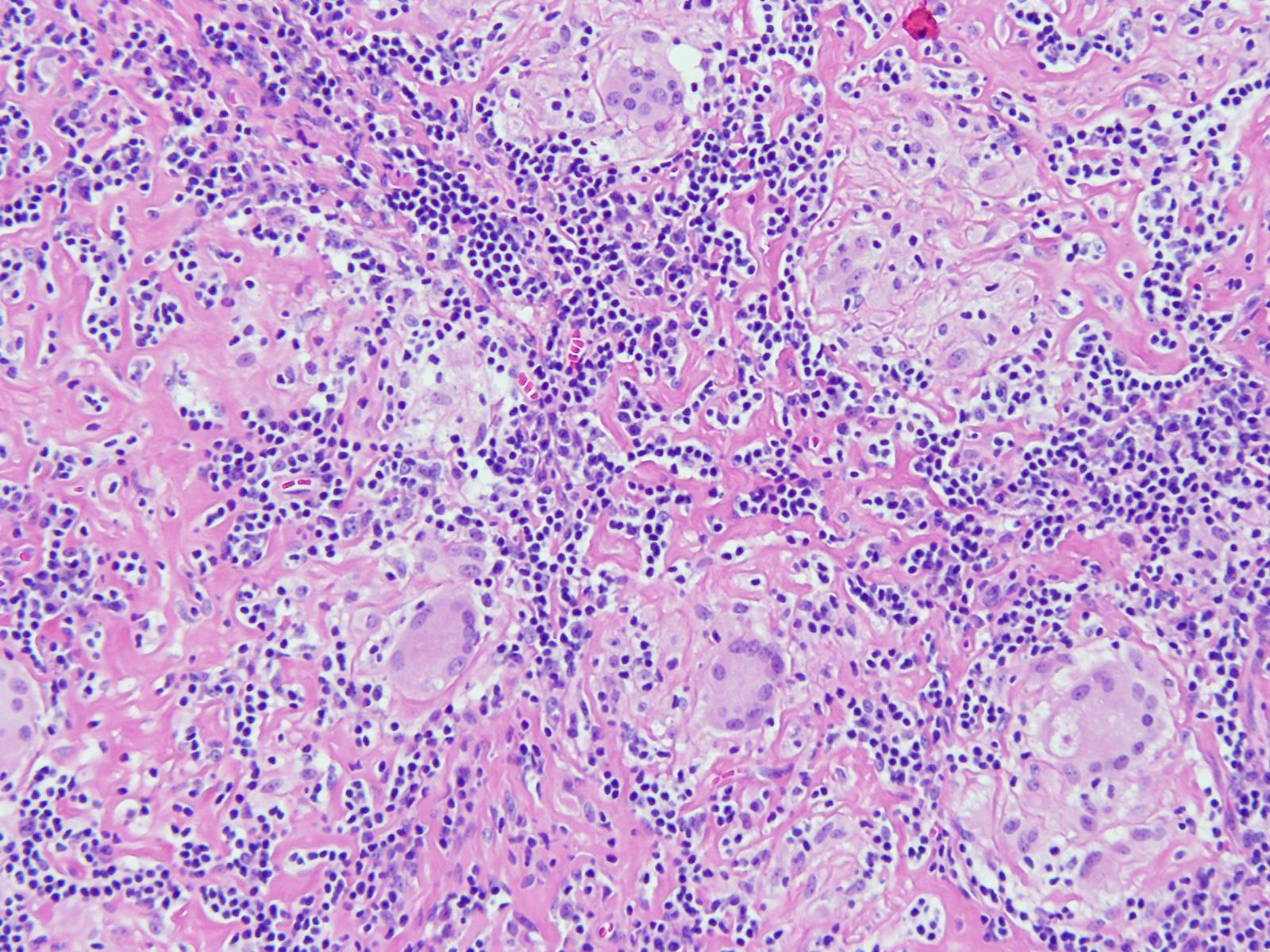

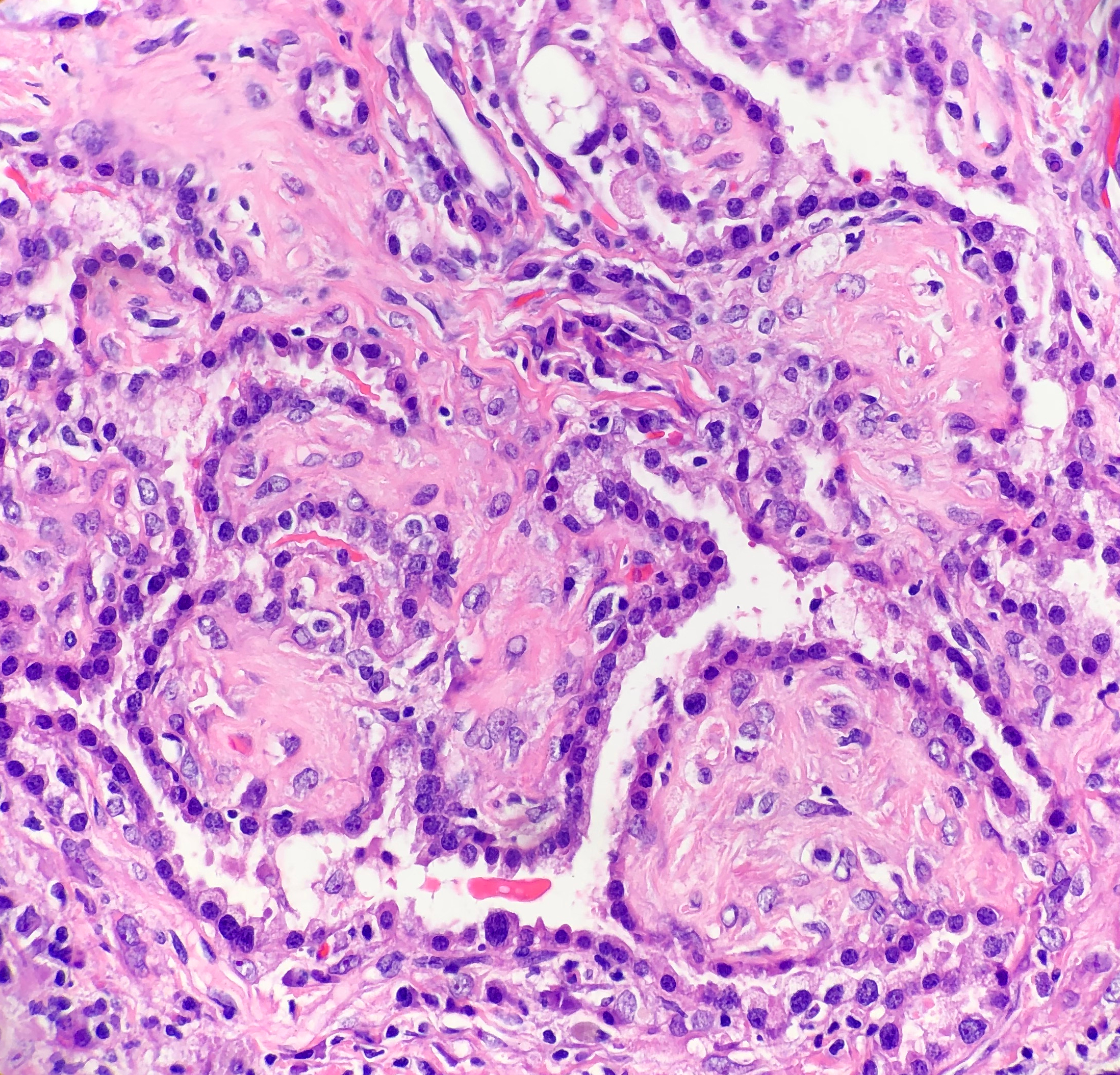

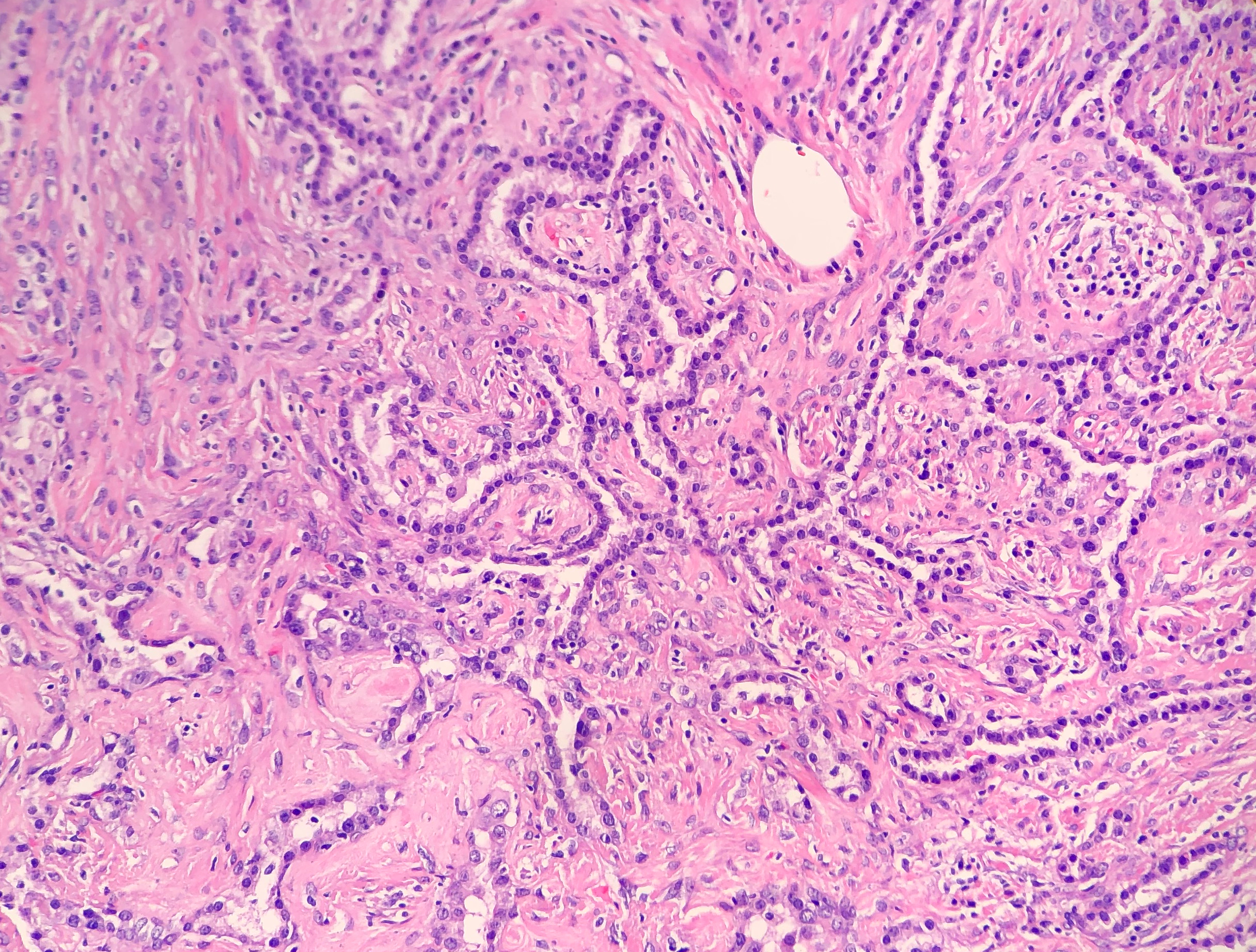

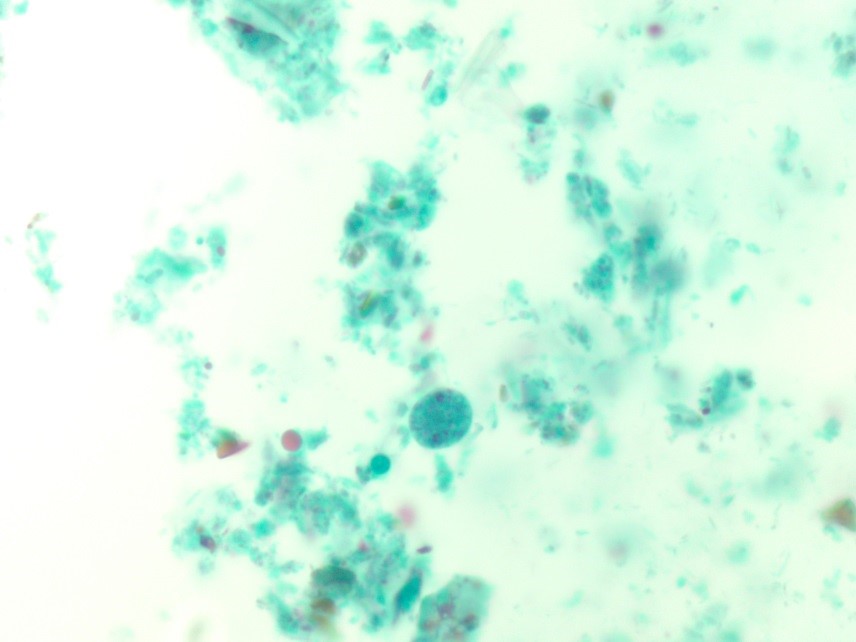

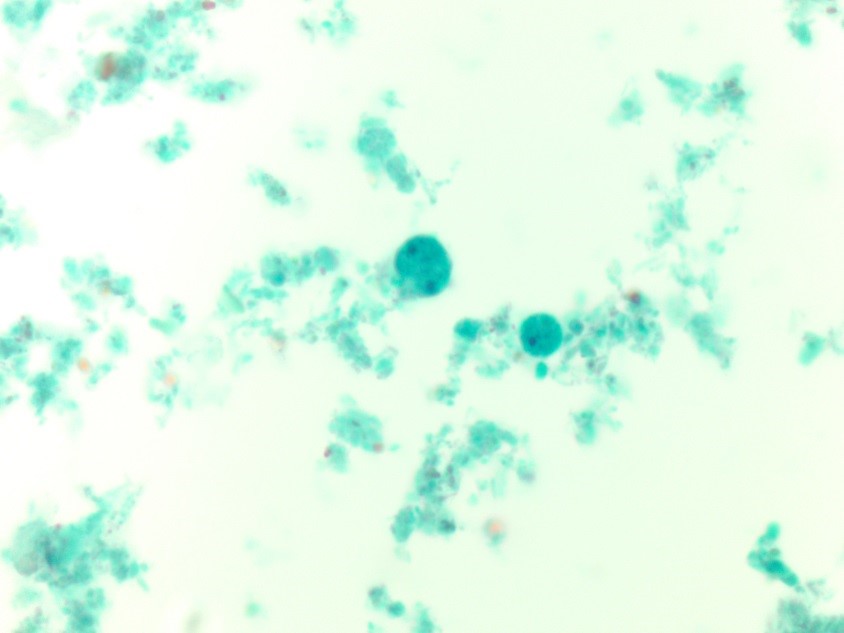

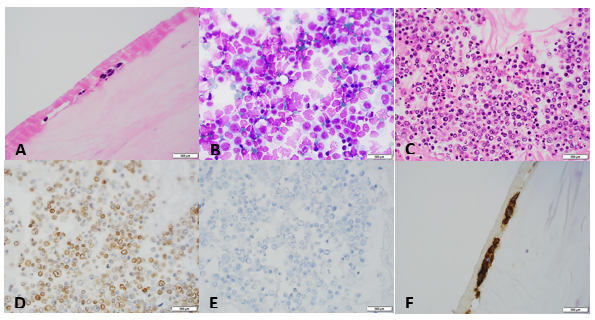

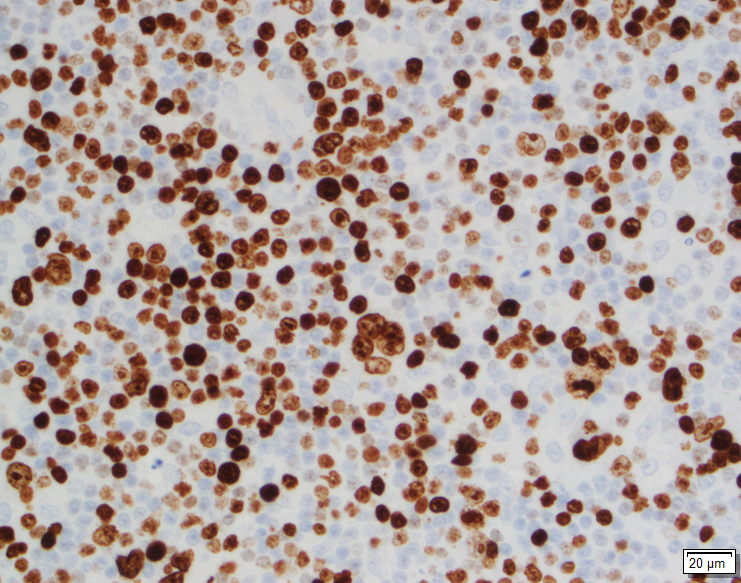

Patients with bacterial endocarditis have an infection of the heart valves or the endoecardial wall that leads to formations of vegetations. These vegetations are composed of thrombotic debris and organisms (Image 2), often associated with destruction of cardiac tissue. Its onset often involves severe symptoms including fever, chills, and weakness. Fever is the most consistent symptom of infective endocarditis, but it may be subtle or even absent in some cases, especially in older adults. Weight loss and flu-like symptoms may also be seen. Left-sided infective endocarditis, as in the case of our patient, will present with murmur in 90% of cases. In long-standing infective endocarditis, patients may present with Roth spots (retinal hemorrhages), Osler nodes (subcutaneous nodules in the digits), microthromboemboli (which appear as splinter hemorrhages under fingernails and toenails), and Janeway lesions (red nontender lesions on the palms or soles).

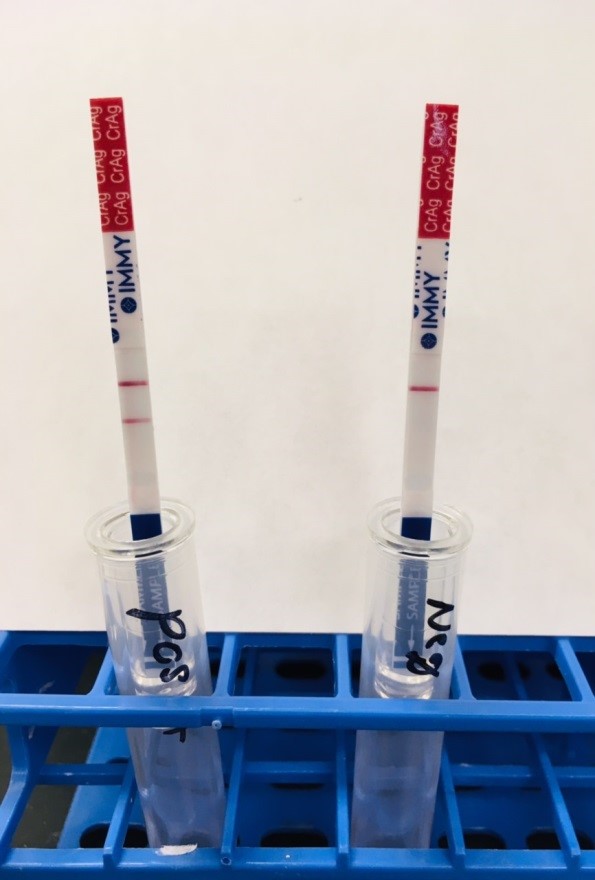

In the laboratory, the diagnosis of S. mitis and other viridians streptococci is often detected via blood culture as in the case of this patient. Once the blood culture bottle becomes positive, a Gram stain is performed, which shows Gram positive cocci in chains (Image 1). These features are helpful in differentiating Streptococcus from Staphylococcus (which appears as clusters instead of chains). Biochemical testing can be done to narrow down the species and identify S. mitis, which is optochin resistant (as opposed to S. pneumonia), acetoin negative (in contrast to most other viridans organisms), and urease negative (which differentiates it from S. vestibularis which is urease positive).

Surgical pathology can also aid in diagnosis by microscopically identifying vegetations on the affected valve (Image 2). Treatment of bacterial endocarditis is usually with penicillin or ceftriaxone, however susceptibility testing should be performed on S. mitis and other viridians streptococci because resistance can occur to penicillin. Blood cultures are followed until they are negative for 72 hours. In the case of our patient, his cultures became negative shortly after he started treatment. Susceptibility testing showed that the organism is sensitive to penicillin and ceftriaxone. The patient was continued on ceftriaxone and is clinically improving.

-Haytham Hasan, MD, is an Anatomic and Clinical Pathology resident at NorthShore Evanston Hospital (University of Chicago).

-Erin McElvania, PhD, D(ABMM), is the Director of Clinical Microbiology NorthShore University Health System in Evanston, Illinois. Follow Dr. McElvania on twitter @E-McElvania.