Case Workup

A 24-year-old female at 34 weeks of gestation was transferred from an outside hospital with history of nephrolithiasis and right side pyelonephritis, for which she underwent stent placement 2 weeks ago. She started experiencing severe pain and muscle spasms in her hip and was unable to move her leg due to the pain. She had decreased appetite and also noted vomiting. Her bilirubin and aminotransferases were found to be elevated. Additionally, her blood gas analysis showed a bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, pH of 7.2 with 99% SpO2. Our clinical chemistry team was consulted on her low pH.

Patient’s laboratory workup is shown in the table below. We first ruled out some common causes of metabolic acidosis, including lactic acidosis and diabetic ketoacidosis. Ingestion of toxic alcohols was ruled out based on normal osmolality and osmolar gap. Normal BUN, creatinine, and their ratio ruled out renal failure.

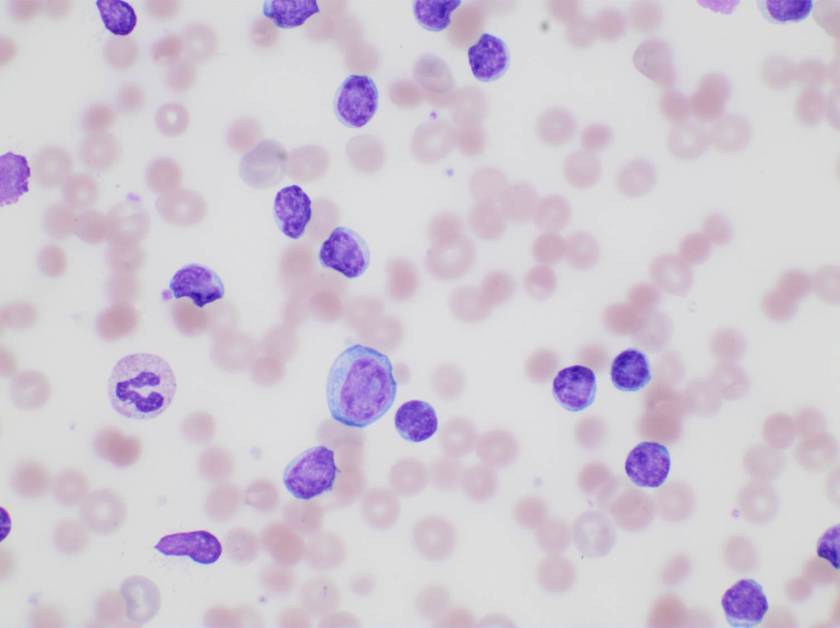

Positive urinary ketones were noted, with an elevated anion gap. Serum beta-hydroxybutyrate was therefore measured and a result of 3.0 mmol/L (ref: <0.4 mmol/L) confirmed ketoacidosis. Patient had no history of diabetes and no recent alcohol consumption. On the basis of excluding other causes, and also considering her decreased appetite and recurrent vomiting, it is believed that ketoacidosis was caused by “starvation.”

| Test | Result | Ref * | Test | Result | Ref * |

| Albumin | 2.0 | 3.5 – 5.0 g/dL | pH | 7.24 | 7.32-7.42 |

| ALK | 139 | 35 – 104 U/L | pCO2 (V) | 21 | 45-51 mmHg |

| ALT | 177 | 5 – 50 U/L | pO2 (V) | 46 | 25-40 mmHg |

| AST | 159 | 10 – 35 U/L | O2 Sat (V) | 72 | 40 – 70 % |

| Total Bili | 2.0 | 0.0 – 1.2 mg/dL | Glucose | 74 | 65-99 mg/dL |

| Direct Bili | 1.5 | 0.0 – 0.3 mg/dL | Urine ketones | 2+ | Negative |

| Lactic acid | 0.9 | 0.5 – 2.2 mmol/L | Urine protein | 2+ | Negative |

| Protein | 6.0 | 6.3 – 8.3 g/dL | Chloride | 104 | 98-112 mEq/L |

| Sodium | 138 | 135-148 mEq/L | CO2 | 9 | 24-31 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 4.6 | 3.5-5.0 mEq/L | Anion gap | 25 | 7-15 mEq/L |

| Creatinine | 0.6 | 0.5 – 0.9 mg/dL | eGFR | >90 | >90 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| BUN | 8 | 6 – 20 mg/dL | Osmolality | 286 | 275 – 295 mOsm/kg |

* Reference ranges are for normal adults, not for pregnant women.

Discussion

With optimal glucose level and sufficient insulin secretion, glucose is converted by glycolysis to pyruvate, which is then converted into acetyl-CoA and subsequently into the citric acid cycle to release chemical energy in the form of ATP. When glucose availability becomes limited, fatty acid is used as an alternative fuel source to generate acetyl-CoA. Ketone bodies are generated in this process, and their accumulation result in metabolic acidosis. In healthy individual, fasting is seldom suspected to be the cause of metabolic acidosis. Sufficient insulin secretion prevents significant free fatty acid accumulation. However, under certain conditions when there is a relatively large glucose requirement or with physiologic stress, 12 to 14 hour fast could lead to significant ketone bodies formation, resulting in overt ketoacidosis (1-3).

Ketoacidosis is most commonly seen in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Similar metabolic changes are seen with poor dietary intake or prolonged fasting and resulting acidosis is referred to as “starvation ketoacidosis” (2). During pregnancy, especially in late pregnancy, there is an increased risk for starvation ketoacidosis, due to reduced peripheral insulin sensitivity, enhanced lipolysis, and increased ketogenesis. In this setting, short period of starvation can precipitate ketoacidosis (1-2, 4). Other cases described with starvation ketoacidosis include patients on strict low-carbohydrate diet (5-6), young infants after fasting (7), and patients with prolonged fasting before surgery (3).

Although starvation ketoacidosis is rare, healthcare provider should be aware of this entity especially in pregnant patients, because late recognition and delay in treatment are associated with a greater risk for impaired neurodevelopment and fetal loss (2). Moreover, given the popularity of low-carbohydrate diet nowadays, starvation ketoacidosis should be considered when assessing patient’s acid-base imbalance in conjunction with their dietary lifestyles.

References

- Frise CJ,Mackillop L, Joash K, Williamson C. Starvation ketoacidosis in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013 Mar;167(1):1-7.

- Sinha N,Venkatram S, Diaz-Fuentes G. Starvation ketoacidosis: a cause of severe anion gap metabolic acidosis in pregnancy. Case Rep Crit Care. 2014;2014:906283.

- Mostert M, Bonavia A. Starvation Ketoacidosis as a Cause of Unexplained Metabolic Acidosis in the Perioperative Period. Am J Case Rep. 2016; 17: 755–758.

- Mahoney CA. Extreme gestational starvation ketoacidosis: case report and review of pathophysiology. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992 Sep;20(3):276-80.

- Shah P,Isley WL. Ketoacidosis during a low-carbohydrate diet. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 5;354(1):97-8.

- Chalasani S, Fischer J. South Beach Diet associated ketoacidosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:45. Epub 2008 Feb 11.

- Toth HL, Greenbaum LA. Severe acidosis caused by starvation and stress. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):E16.

-Xin Yi, PhD, DABCC, FACB is a board-certified clinical chemist. She currently serves as the Co-director of Clinical Chemistry at Houston Methodist Hospital in Houston, TX and an Assistant Professor of Clinical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College.