Case history

A 50 year old female with a past medical history significant for Sjogren’s syndrome and ventricular tachycardia s/p ICD placement presented for a routine chest X-ray in which a 1.8 cm spiculated left upper lobe lung mass was identified. A subsequent PET scan revealed FDG avidity. Other Imaging revealed no lymphadenopathy. The patient is a non-smoker and has no other comorbidities. A core needle biopsy with fiducial placement was performed.

Diagnosis

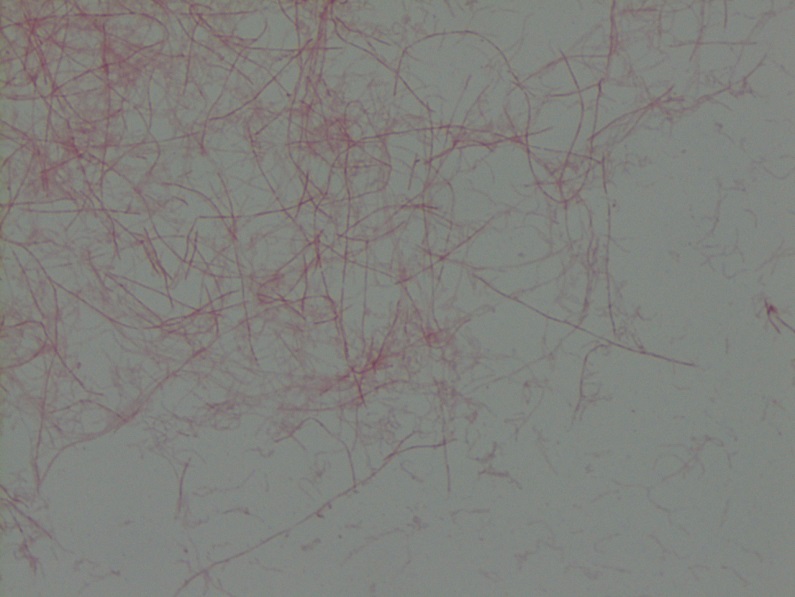

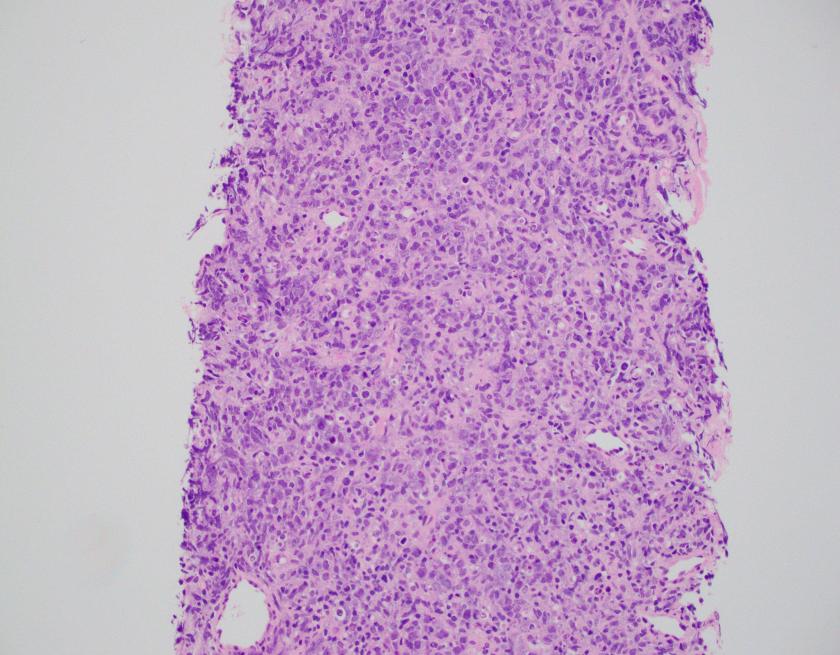

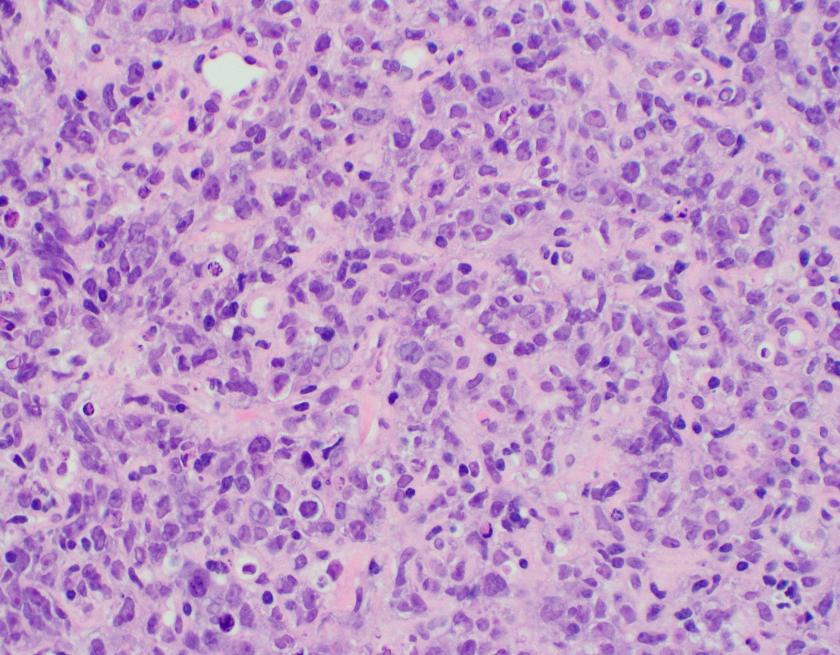

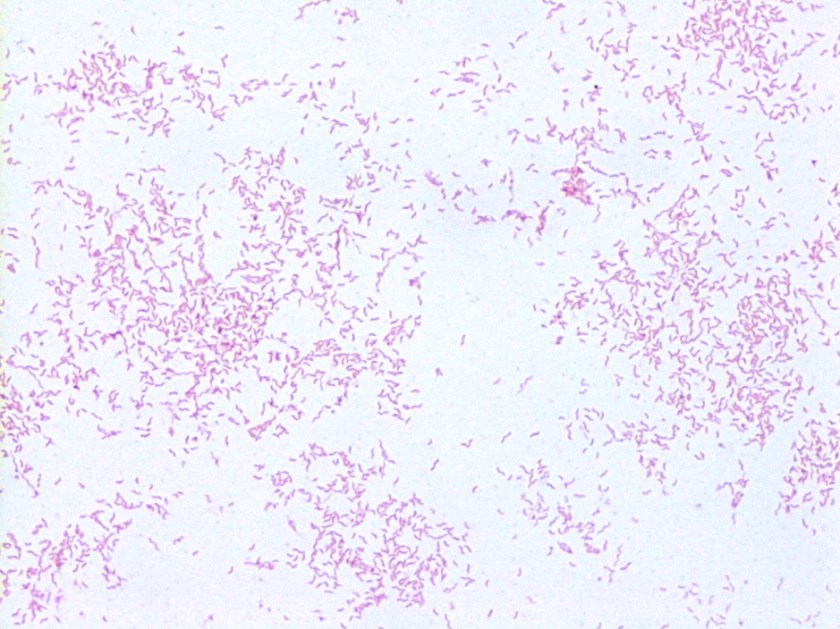

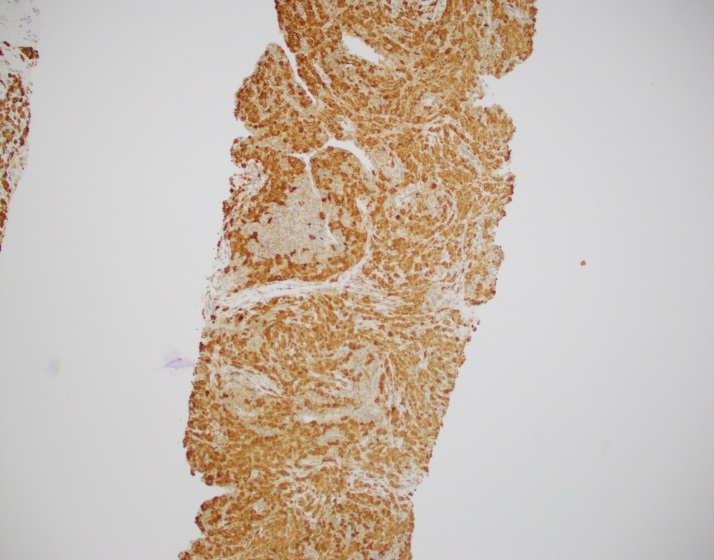

Sections of lung core biopsy material show numerous histiocytes containing eosinophilic intracytoplasmic globular inclusions. An admixed population of plasma cells are seen which are present in aggregates along with mature appearing lymphocytes. The plasma cells also demonstrate globular inclusions within their cytoplasm.

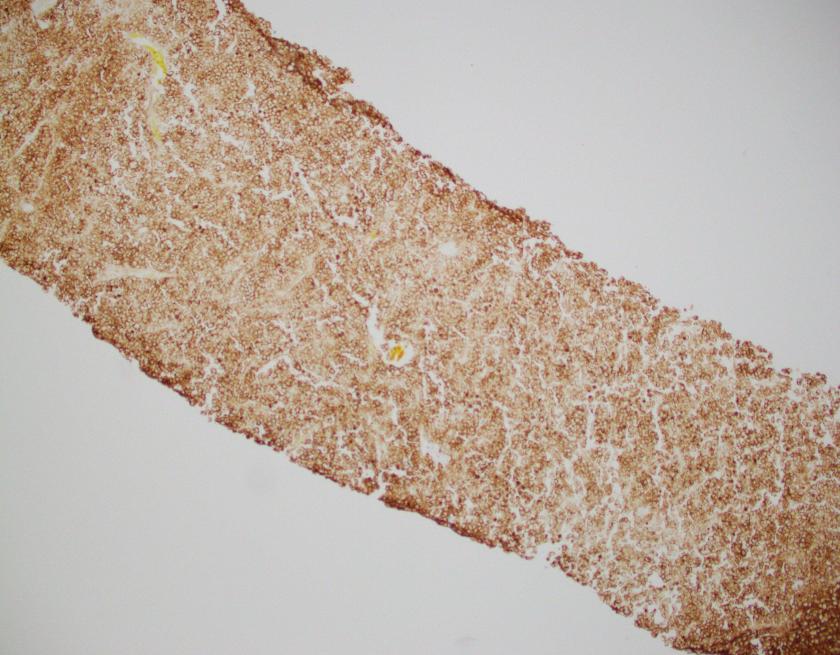

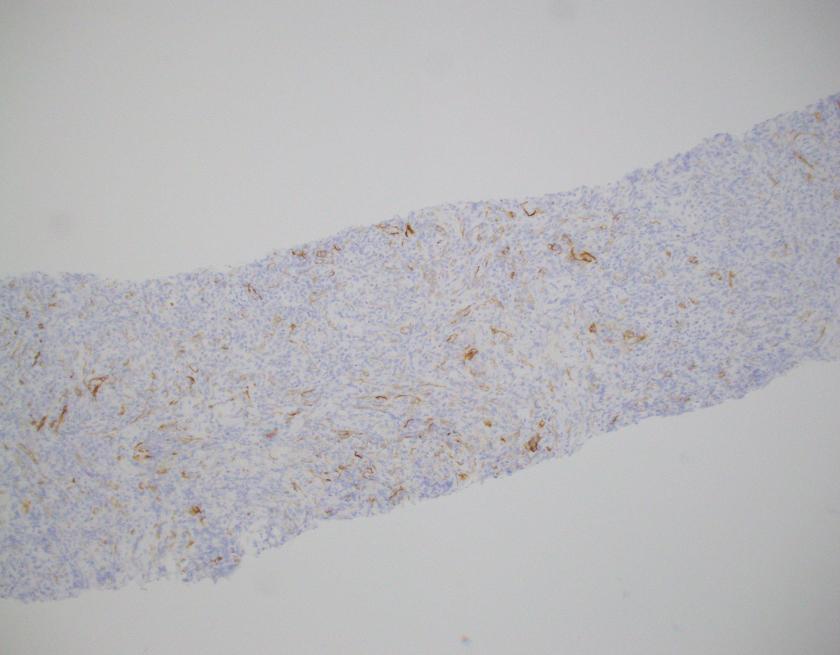

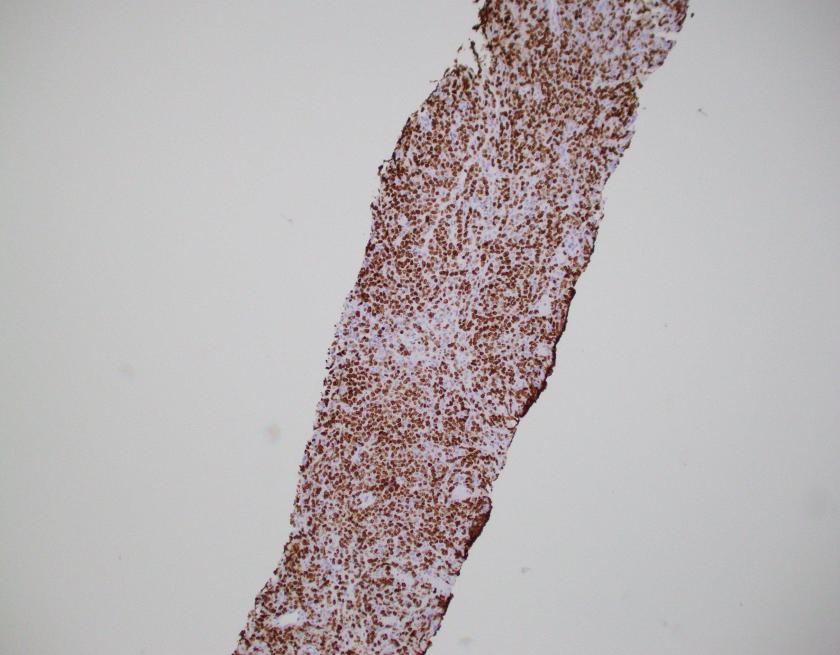

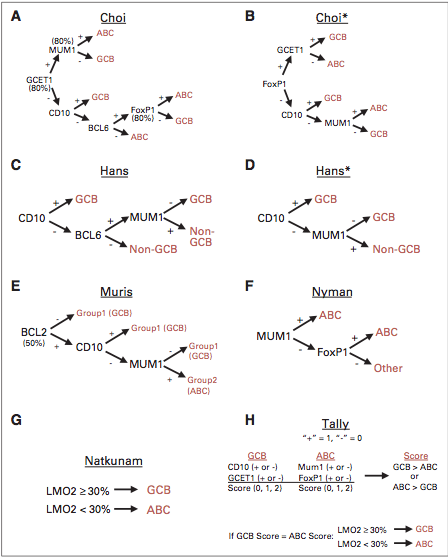

By immunohistochemistry, CD3 highlights scattered mature T-cells while CD20 highlights B-cells present in focal aggregates. Numerous plasma cells are present and are positive for CD138, CD79a, BCL2, and MUM1. By in situ hybridization, plasma cells are greatly kappa predominant. IgG is positive in the majority of the plasma cells with only rare cells staining for IgA and IgM. CD68 is positive in the numerous histiocytes.

IGH gene rearrangement studies by PCR demonstrated was positive, indicating a clonal population.

Overall, the findings are consistent with a crystal-storing histiocytosis with an associated plasma cell neoplasm or low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder.

Following the diagnosis, the patient received stereotactic body radiation therapy given the localized findings.

Discussion

In this case, the findings are morphologically consistent with crystal-storing histiocytosis (CSH), which is a rare lesion that is the result of intralysosomal accumulation of immunoglobulin. The immunoglobulin is stored as crystalline structures within histiocytes that occupy the vast majority of a mass forming lesion. Multiple sites can be involved, which include bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and kidney. Most often, the lesion is confined to a single site but occasional generalized forms with multiple organ involvement have been described. CSH is also often associated with B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders or plasma cell dyscrasias, but rarely are the result of chronic inflammatory conditions.

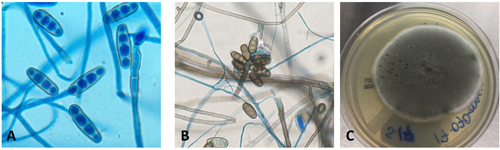

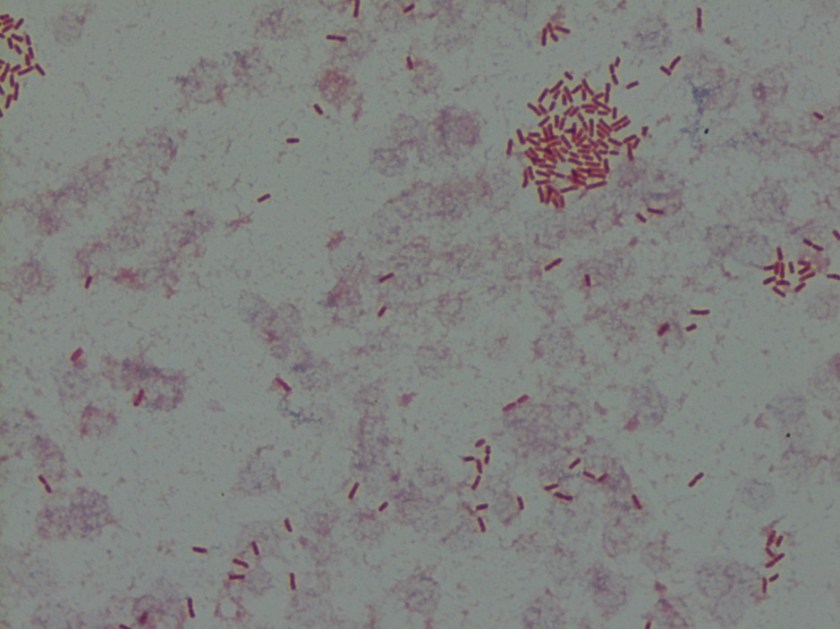

The assessment of CSH requires excellent staining to identify the quality of the histiocytes. As mentioned, CSH will show intracytoplasmic inclusions that are eosinophilic in nature. Mimickers of CSH include mycobacterial and fungal infections, mycobacterial spindle cell pseudotumor, malakoplakia, HLH, storage disorders such as Gaucher’s, as well as histiocytic lesions such as xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytiosis, fibrous histiocytoma, Rosai Dorfman disease and rarely other eosinophilic tumors such as rhabdomyoma, granular cell tumor, and oncocytic neoplasms.1

A thorough review of the literature as well as a clinicopathologic study by Kanagal-Shamanna R et al revealed that the localized type of CSH was the dominant presentation in which over 90% of cases showed isolated masses. Per previous reviews, localized lesions were often found in the head and neck as well as lung.2 A study group in which 13 cases that showed CSH, 12 demonstrated an underlying lymphoma or plasmacytic neoplasm. Interestingly, in 5 of the cases, the histiocytic infiltrate was so prominent and dense that it obscured the underlying neoplasm. In these particular cases, immunohistochemistry and PCR were of great importance.

Although the majority of cases of CSH are the result of an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder or plasma cell neoplasm, rare cases of report inflammatory processes have been described, particularly in the setting of an immune mediated process such as rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn disease.

Overall, although a rare entity, it is important to be aware of CSH and its mimickers as this can be an elusive diagnosis to make, especially when the histiocytic infiltrate is dense.

References

- Kanagal-Shamanna R, et al. “Crystal-Storing Histiocytosis: A Clinicopathologic Study of 13 Cases,” Histopathology. 2016 March; 68(4): 482-491.

- Dogan S, Barnes L, Cruz-Vetrano WP “Crystal-storing histiocytosis: a report of a case, review of the literature (80 cases) and a proposed classification,” Head Neck Pathol. 2012; 6:11-120.

-Phillip Michaels, MD is a board certified anatomic and clinical pathologist who is a current hematopathology fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well as pathology resident education, especially in hematopathology and molecular genetic pathology.