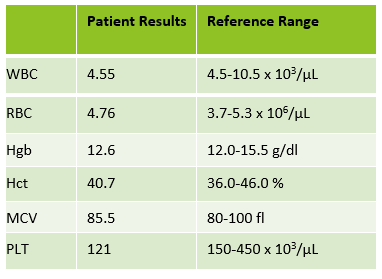

A 73 year old African American female had a CBC ordered as part of routine pre-op testing before knee surgery. The order for a CBC/auto differential and was run on our Sysmex XN-3000. CBC results were unremarkable, with the exception of a decreased platelet count. However, the instrument flagged “Suspect, Left shift?” and a slide was made for review. The CBC results are shown in Table 1 below.

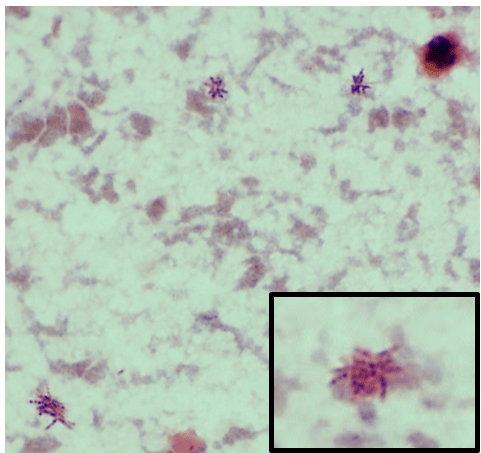

Pelger-Huët anomaly (PHA), is a term familiar to medical laboratory professionals, but mostly from textbook images. PHA is considered to be rare, affecting about 1 in 6000 people. PHA has been found in persons of all ethnic groups and equally in men and women. The characteristic, morphologically abnormal neutrophils were first described by Dutch hematologist Pelger in 1928. He described neutrophils with dumbbell shaped, bi-lobed nuclei. The term ‘pince-nez’ has also been used to describe this spectacle shaped appearance. Pelger also noted that, in addition to hyposegmentation, there is an overly coarse clumping of nuclear chromatin. In 1931, Huët, a Dutch pediatrician, identified this anomaly as an inherited condition.

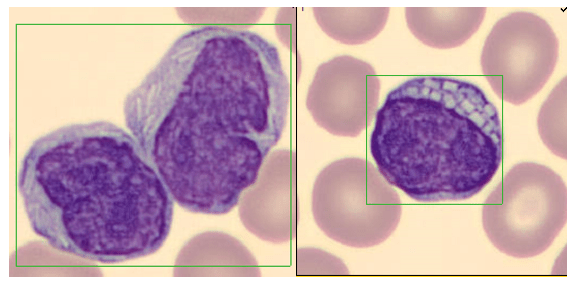

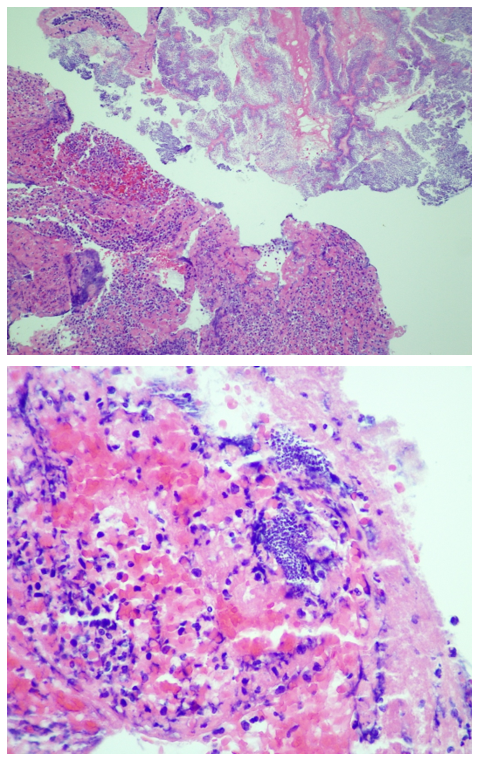

Pelger-Huët anomaly is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the lamina B receptor (LBR) gene on band 1q42. This defect is responsible for the abnormal routing of the heterochromatin and nuclear lamins, proteins that control the shape of the nuclear membrane.2 Because of this mutation, nuclear differentiation is impaired, resulting in white blood cells with fewer lobes or segments. In classic inherited PHA, cells are the size of mature neutrophils and have very clumped nuclear chromatin. About 60-90% of these neutrophils are bi-lobed either with a thin filament between the lobes, or without the filament. About 10-40% of total neutrophils in PHA have a single, non-lobulated nucleus. Occasional normal neutrophils with three-lobed nuclei may be seen.1 Despite their appearance, Pelger-Huët cells are considered mature cells, function normally and therefore can fight infection. It is considered a benign condition; affected individuals are healthy and no treatment is necessary for PHA.

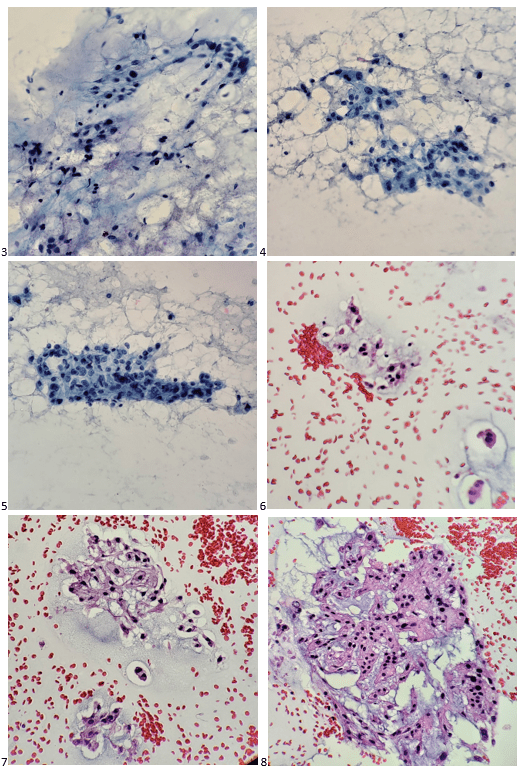

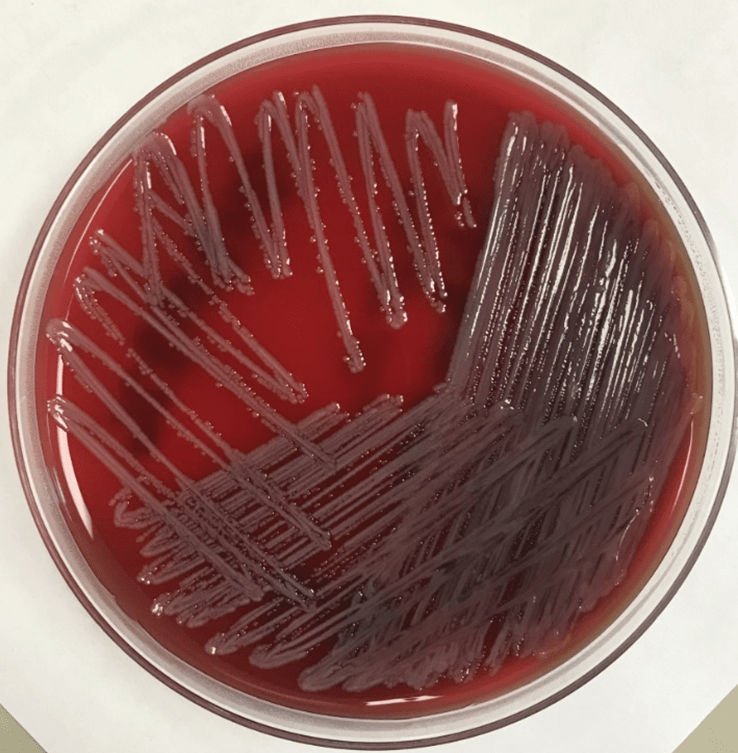

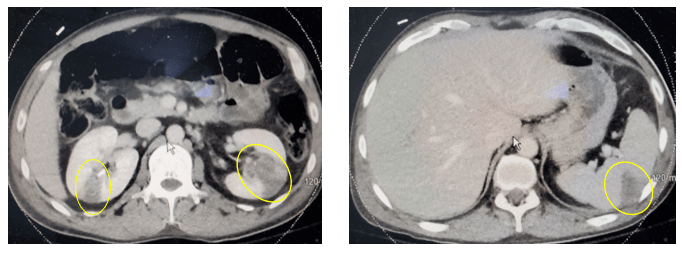

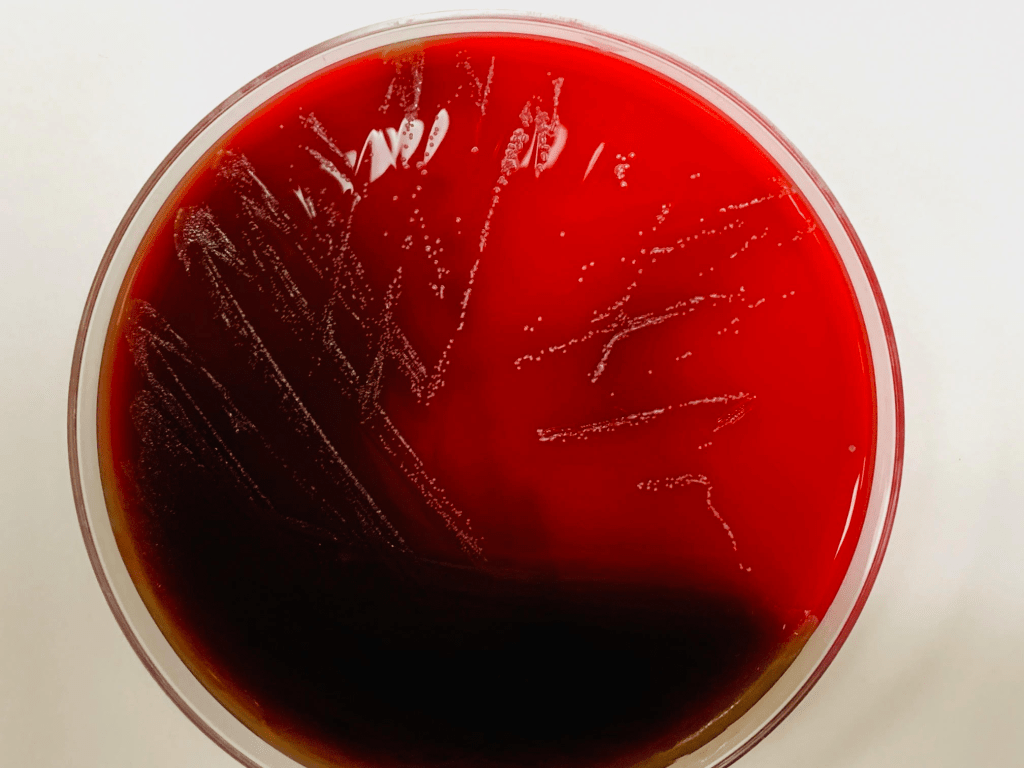

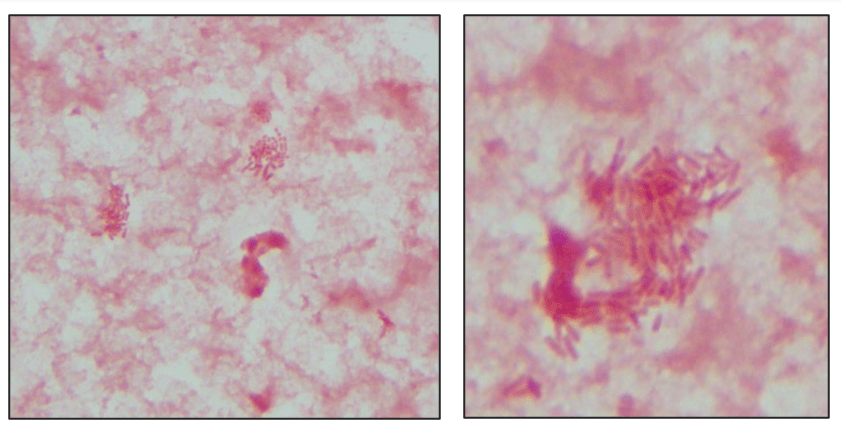

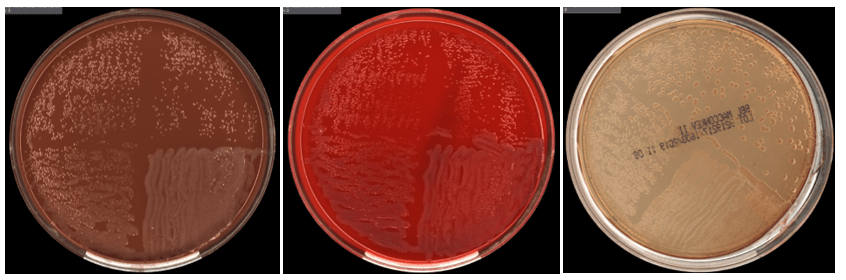

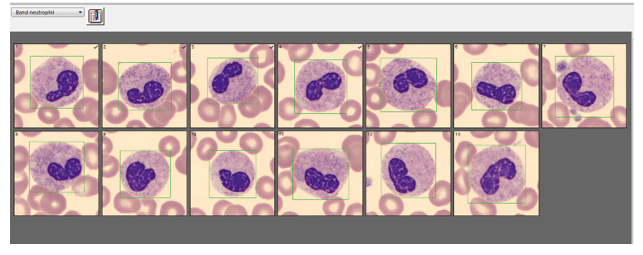

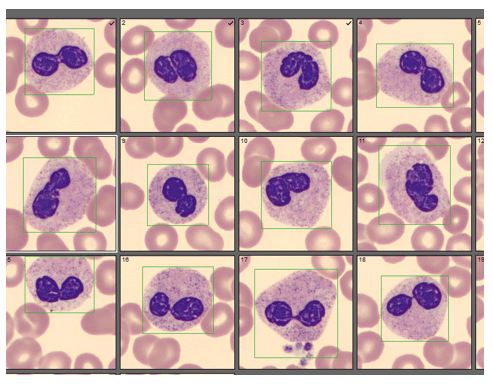

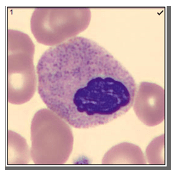

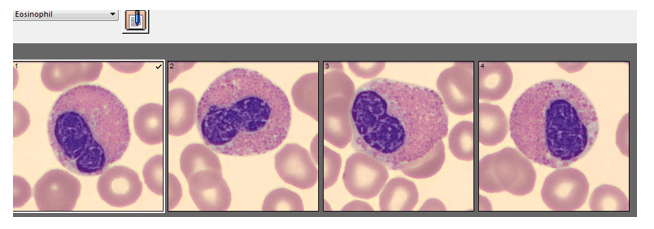

Automated instruments may flag a left shift when they detect these Pelger-Huët cells. In this patient, the analyzer flagged a left shift and a slide was made and sent to CellaVision. The CellaVision pre-classified the Pelger-Huët cells as neutrophils, bands, and myelocytes. All of the neutrophil images were either bi-lobed or non-lobed forms. None of the neutrophils had more than 2 lobes. Eosinophils also had poorly differentiated nuclei. Cell images from this patient can be seen in Images 1-4.

If PHA is considered benign, with no clinical implications, why is it important to note these cells on a differential report? This slide was referred to our pathologist for a review. The patient had several previous CBC orders, but no differentials in our LIS. The pathologist reviewed the slide and, based on 100% of these neutrophils being affected, he reported “Pelger-Huët cells present. The presence of non-familial Pelger-Huët anomaly has been associated with medication effect, chronic infections and clonal myeloid neoplasms.” Thus, the importance of reporting this anomaly if seen on a slide. If the instrument flags a left shift, this is typically associated with infection. If these cells are misclassified as bands and immature granulocytes, with no mention of the morphology, there would be a false increase in bands reported and the patient may be unnecessarily worked up for sepsis.

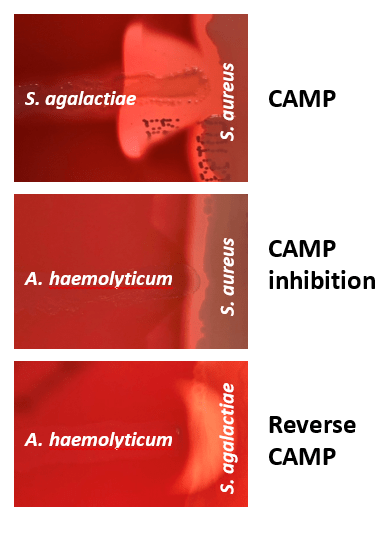

An additional reason for reporting the presence of Pelger-Huët cells is that pelgeroid cells are also seen in a separate anomaly, called acquired or pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly (PPHA). PPHA is not inherited and can develop with acute or chronic myelogenous leukemia and in myelodysplastic syndrome. A type of PPHA may also be associated with infections or medications. Certain chemotherapy drugs, immunosuppressive drugs used after organ transplants, and even ibuprofen have been recognized as triggers for PPHA. PPHA caused by medications is typically transient and resolves after discontinuation of the drug. To add to causes, most recently, there have been studies published that report PPHA in COVID-19 patients.3

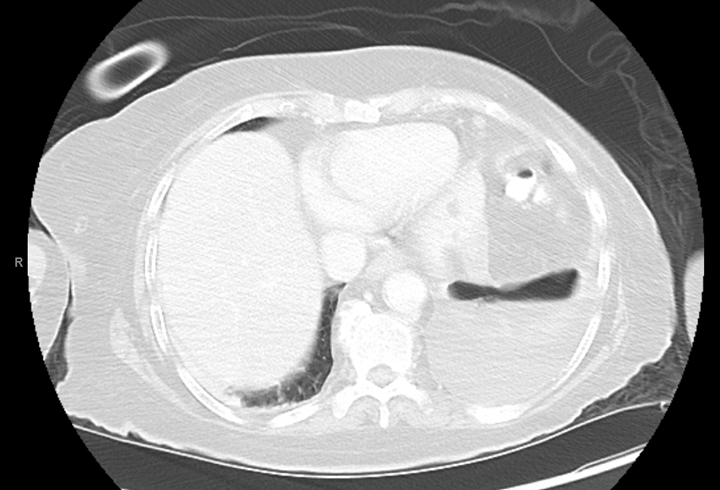

With several different causes of PHA/PPHA, a differential diagnosis is important. Is this a benign inherited condition, a drug reaction that will self-resolve after therapy is stopped, or something more serious? If Pelger-Huët cell are reported, it is important for the provider to correlate this finding with patient symptoms, treatments and history. There was no medication history and little other medical history in our case patient’s chart, and no mention of inherited PHA. The patient had also been tested for COVID-19 with her pre-op testing and was COVID negative. On initial identification of Pelger-Huët, a benign diagnosis that needs no treatment or work up would be the best outcome, so an attempt could be made to determine if the patient has inherited PHA. If other family members are known to have this anomaly, this would be the likely diagnosis as PHA is autosomal dominant. Family members can also easily be screened with CBC and manual differential. Molecular techniques are available to confirm PHA but are not routinely used. In the absence of this anomaly in other family members, it would need to be determined if the patient was on any medications that can cause pelgeroid cells. Inherited PHA and drug induced PPHA should be ruled out first because PPHA can also be predicative of possible development of CML or MDS. Considering this cause first could lead to unnecessary testing that might include a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy. Additionally, the entire clinical picture should be reviewed because in PPHA associated with myeloproliferative disorders there is usually accompanying anemia and thrombocytopenia and the % of pelgeroid cells tends to be lower.

Today most clinical laboratories have instruments that do automated differentials, and we encourage physicians to order these because they are very accurate and count thousands of cells compared to the 100 cells counted by a tech on a manual differential. Automated differentials are desirable for consistency and to improve turnaround times. Yet, it is important to know when a slide needs to be reviewed under the scope or with CellaVision. If a patient presents with a normal WBC and a left shift on the auto diff with no apparent reason, pictures can reveal important clinical information. Awareness of different causes of PHA/PPHA can relieve anxiety in patients and prevent extensive, unnecessary testing and invasive procedures.

References

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/957277-followup updated 8/4/2020

- Ayan MS, Abdelrahman AA, Khanal N, Elsallabi OS, Birch NC. Case of acquired or pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2015;2015(4):248-250. Published 2015 Apr 1. doi:10.1093/omcr/omv025

- Alia Nazarullah, MD; Christine Liang, MD; Andrew Villarreal, MLS; Russell A. Higgins, MD; Daniel D. Mais, MD. Am J Clin Peripheral Blood Examination Findings in SARS-CoV-2 Infection . Pathol. 2020;154(3):319-329.

-Becky Socha, MS, MLS(ASCP)CM BB CM graduated from Merrimack College in N. Andover, Massachusetts with a BS in Medical Technology and completed her MS in Clinical Laboratory Sciences at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. She has worked as a Medical Technologist for over 30 years. She’s worked in all areas of the clinical laboratory, but has a special interest in Hematology and Blood Banking. When she’s not busy being a mad scientist, she can be found outside riding her bicycle.