Case History

A 27 year old African American male presented to the emergency department with confusion and abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for a 100 pound unintended weight loss and oral candidiasis which prompted a recent diagnosis of HIV. He was prescribed anti-retroviral therapy and antibiotic prophylaxis with which he reported compliance. Currently, he had no fever or chills. An abdominal CT scan showed an enlarged liver & spleen, generalized lymphadenopathy and a small amount of fluid. Significant lab work included anemia with a platelet count of 18,000 TH/cm2, absolute CD4 100 cells/cm2 (reference range: 506-3142 cells/ cm2) and a HIV viral load of 4,871 vc/mL. Given the concern for an infectious process, the infectious disease service was consulted and the patient underwent a thorough infectious work up including lumbar puncture, was started on board spectrum antibiotics and antifungals and was placed in airborne isolation until Mycobacterium tuberculosis could be ruled out.

Laboratory Identification

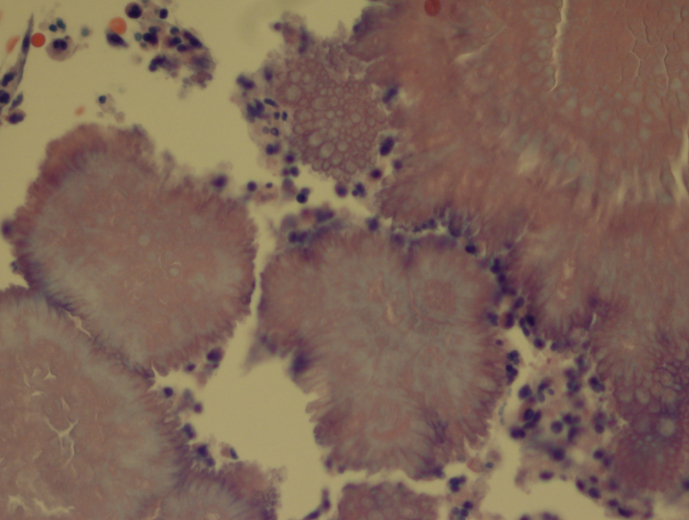

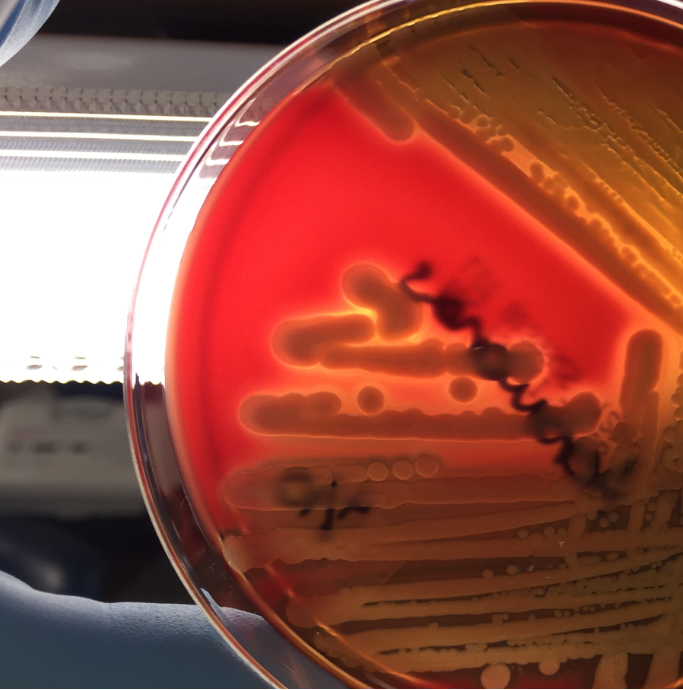

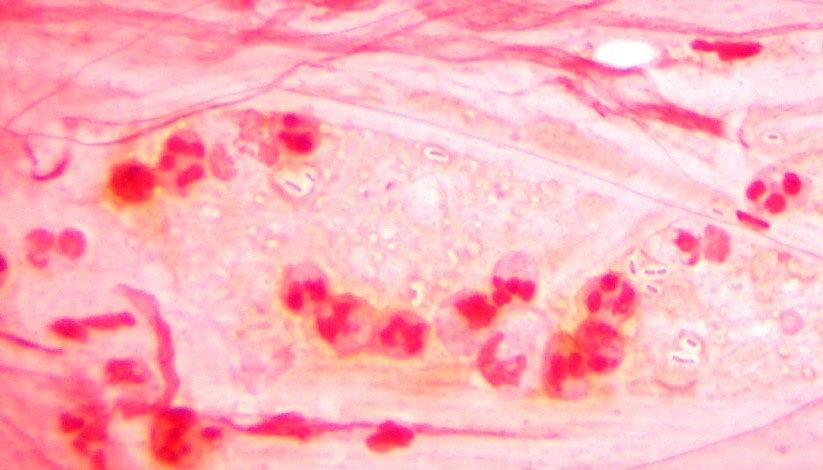

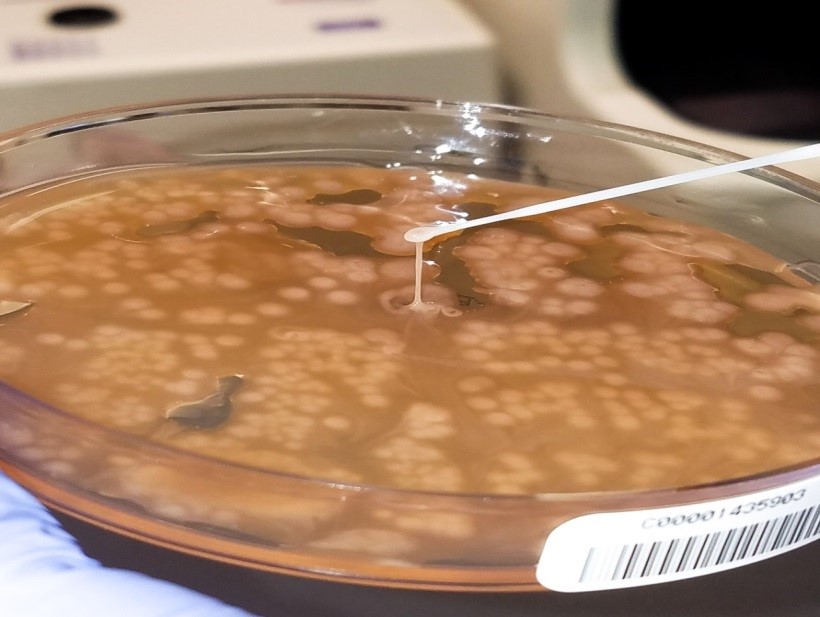

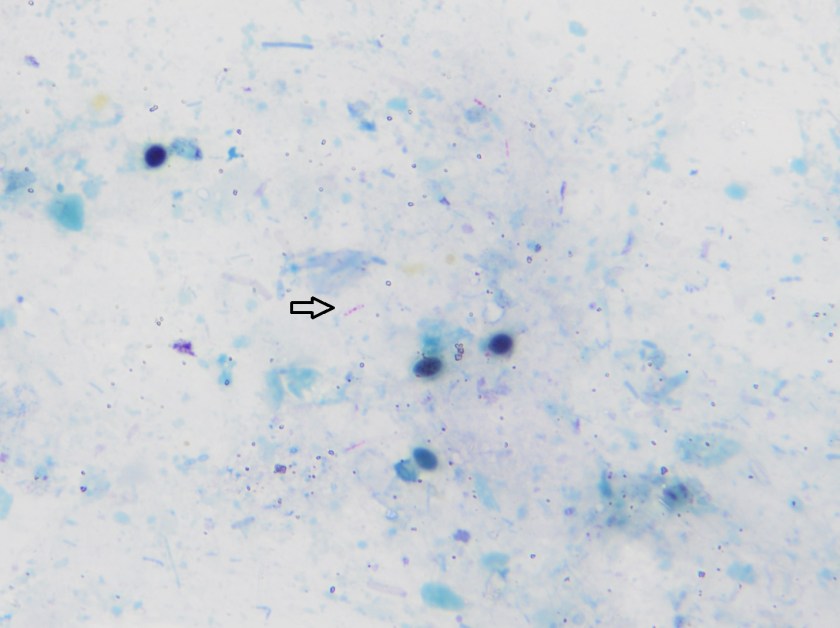

Initial diagnostic testing for bacterial, fungal and viral pathogens was negative. Three concentrated sputum AFB smears as well as a TB PCR were negative. The quantiferon gold TB test was also negative. The physician additionally ordered AFB blood and stool cultures. The direct smear from the stool specimen showed rare, beaded acid fast bacilli in a background of bacteria and yeast normally present in the stool via Kinyoun stain (Images 1 & 2). The specimen was sent to the department of health for additional work up. There was growth after 21 days incubation and Mycobacterium avium complex was identified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Discussion

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is a slow growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) frequently involved in human disease. Historically, it was classified as Runyon group III which are non-chromogens and do not produce pigment regardless of culture conditions. The group encompasses two taxa, M. avium and M. intracellulare. The species M. avium can further be classified into four subspecies: subsp. avium, subsp. silvaticum, subsp. paratuberculosis and subsp. hominissuis. Of interest, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis can often be seen in association with Crohn’s disease.

In general, MAC organisms have low pathogenicity, but in the setting of those with lung disease (including cystic fibrosis), heavy smokers, immunocompromised patients and those with HIV, it is a well-known cause of disease. Infections with MAC can range from localized mycobacterial lymphadenitis and isolated pulmonary disease to bacteremia with dissemination to almost any organ. The organisms are located in circulating monocytes and further spread most commonly to the lungs, gastrointestinal tract and lymph nodes. In the case of HIV positive patients, MAC is the most common environmental NTM causing disease, especially in those with CD4 counts less than 100 cells/mm3 who are more likely to have disseminated disease.

In order to diagnosis MAC infections, specimens from blood, sputum, lymph nodes and other tissues are preferred. In addition, stool may also be an acceptable alternative in HIV patients if other specimens are negative or unable to be obtained. However, the sensitivity of a direct stool smear is only 32 to 34% making it not a very effective approach to identifying those at risk for disseminated infections. Once the culture has growth, various methods can be used to identify MAC, including phenotypic methods, DNA probe testing, HPLC, pyrosequencing and other forms of PCR & sequencing.

In the case of our patient, he was started on M. tuberculosis therapy: rifabutin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide & ethambutol (RIPE) until TB was ruled out. At that time, he was removed from isolation and switched to a drug regimen that included azithromycin, rifabutin and ethambutol. He showed clinical improvement and his cell counts, renal function and liver enzymes trended to normal ranges.

-Lisa Stempak, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. She is certified by the American Board of Pathology in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology as well as Medical Microbiology. She is the Director of Clinical Pathology as well as the Microbiology and Serology Laboratories. Her interests include infectious disease histology, process and quality improvement and resident education.