I’ve found that our cytologists have a love-hate relationship with thyroids. Pathologists do too. Or it could be that we see so many goiters (50%) and follicular lesions or atypia of undetermined significance (35%) that the rare papillary thyroid carcinoma is a gem in our eyes. Minimally-invasive thyroid FNAs are instrumental in the management of thyroid nodules. It’s important to note that due to lack of architecture and assessment of capsular invasion, cytologic diagnoses may be limited, and prior to referring the patient for a potentially unnecessary surgery, various molecular tests can be utilized. The ongoing evolution of molecular testing on thyroid FNAs help classify indeterminate and suspicious cytology diagnoses (Bethesda Categories III and IV), examining the risk of malignancy or detecting the presence of genetic alterations, which help guide surgical intervention versus surveillance. This post (the first edition) features a series of our classic Bethesda Category VI specimens, which bypassed the need for risk classification and defaulted in surgical intervention based on guidelines at the time of diagnosis. It is worth mentioning that many of these cases occurred prior to the implementation of the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS), so to preserve the accuracy of patient history, a TI-RADS score will not be assumed.

Case 1

Okay, I know I said Bethesda VI, but let’s kick this series off with a Bethesda Category IV case. Thankfully, the patient decided to undergo a partial thyroidectomy, yielding a beautiful tissue follow-up. A 59-year-old male with newly diagnosed melanoma of the neck underwent imaging for staging purposes. A left thyroid nodule was identified measuring 3.0 centimeters. The patient presented for an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration.

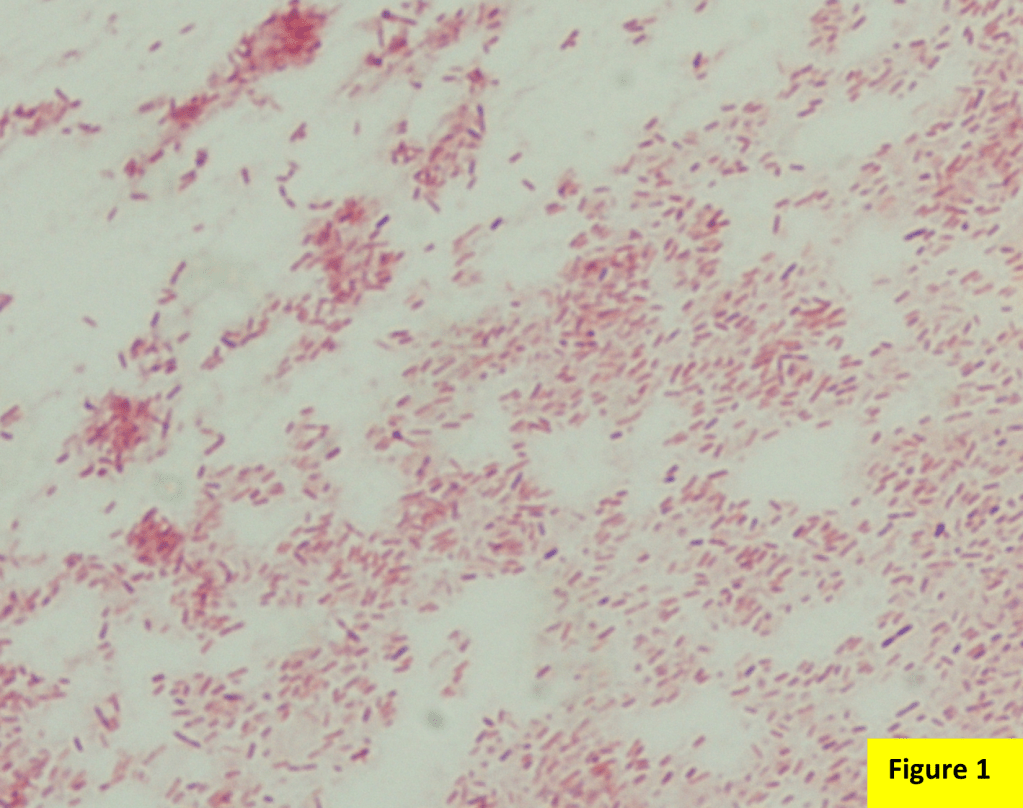

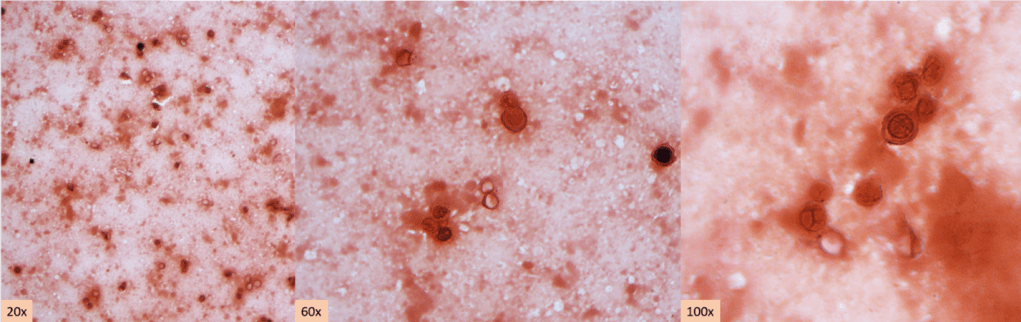

Abundant oncocytic Hürthle cells, some with mild atypia, were identified, suggestive of Hürthle cell neoplasm (Images 1-3). With a lack of lymphocytes, we did not feel comfortable suggesting Hashimoto’s (lymphocytic) thyroiditis. Immunostains performed on cell block sections show the tumor cells are positive for TTF-1, focally positive for thyroglobulin and AE1/AE3 (rare), and negative for calcitonin. The morphology and immunohistochemical profile support the above diagnosis.

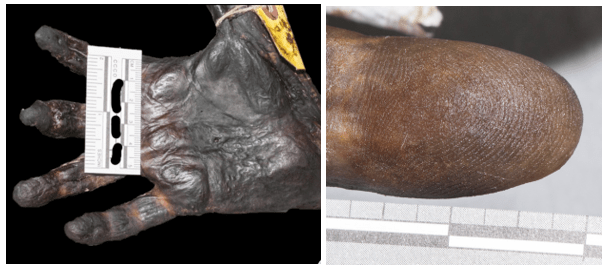

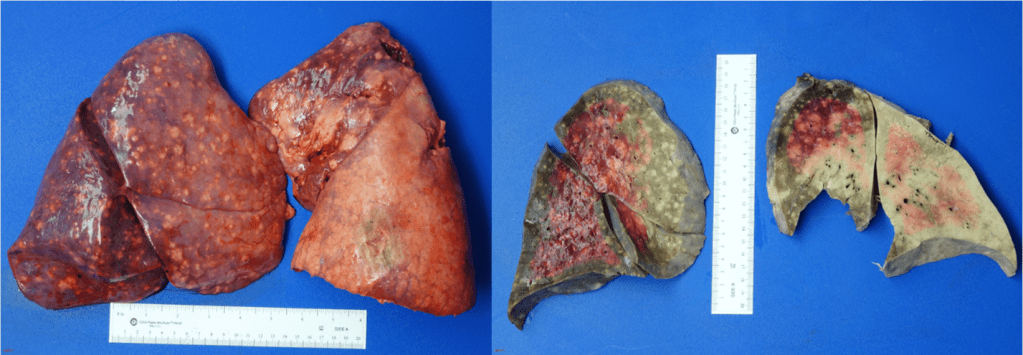

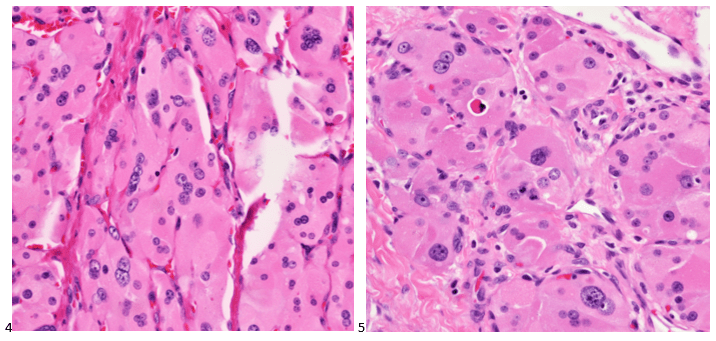

The patient underwent a left lobectomy and isthmusectomy. Pathology showed a 3.2 cm Hürthle cell carcinoma (Images 4-5) in the left lobe of the thyroid (encapsulated with a foci of capsular invasion without vascular invasion) as well as a 0.3 cm micropapillary carcinoma. Since Hürthle cell carcinoma does not typically concentrate radioiodine, the patient would not be responsive to treatment with radioactive iodine. Therefore, there would be less benefit derived from treating the smaller right lobed nodules (which don’t meet biopsy criteria) from remnant ablation. The patient had a clinically limited stage thyroid cancer. The patient is monitored with neck ultrasounds rather than serum thyroglobulin testing (due to the remaining right lobe).

Cytology diagnosis: Hürthle cell neoplasm.

Pathology diagnosis: Hürthle cell carcinoma.

Case 2

A 53-year-old female with no prior history presented with fatigue and a self-palpated right thyroid nodule and normal thyroid function tests. She reported an extensive family history of hypothyroidism. On thyroid ultrasound, the right upper pole thyroid nodule measured 2.0 x 2.0 x 1.8 cm and was mostly solid and hypoechoic with microcalcifications. Pre-intervention serum calcitonin measured 1634 pg/mL. The patient underwent an FNA of the thyroid nodule and the smears are depicted below.

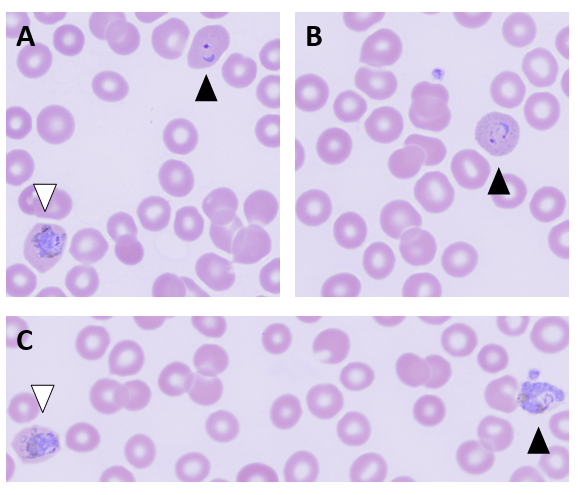

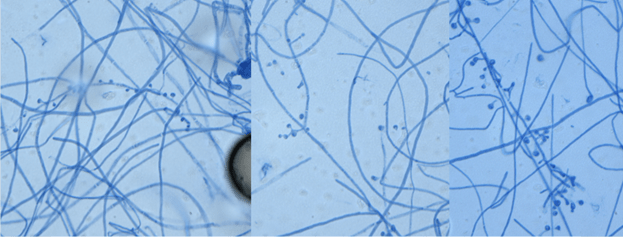

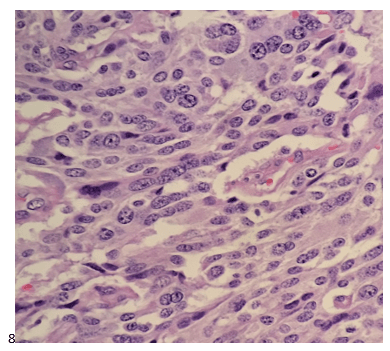

Cells appear plasmacytoid and appear both isolated and in clusters (Image 6). The nuclei are eccentrically placed, and the chromatin has a salt and pepper appearance akin to a neuroendocrine tumor (Image 7-8). Also identified were pink granules and intranuclear pseudoinclusions (Images 6-7). We performed immunohistochemical stains on paraffin sections of the cell block. Tumor cells show positive staining for calcitonin, chromogranin, mCEA, and TTF-1, while negative staining for thyroglobulin and CD45.

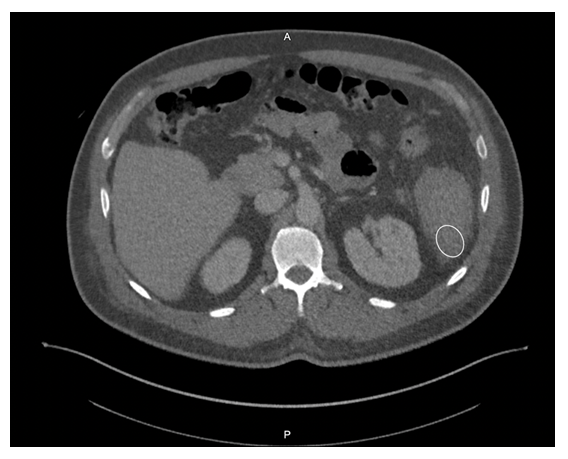

Following the diagnosis, the patient had a CT scan for staging purposes. Multiple lymph nodes in the right cervical chain were identified. the patient at a clinical stage IVA diagnosis. In the interim, the patient had a total thyroidectomy which revealed medullary thyroid carcinoma of the right lobe measuring 2.2 cm, a micropapillary carcinoma of the left lobe measuring 0.1 cm (Image 8). Lymphovascular invasion was not identified, the inked surgical resection margins are free of carcinoma, and metastatic medullary carcinoma was identified in 6 of the 77 lymph nodes removed during the central compartment lymph node dissection, and bilateral cervical lymphadenectomies. The calcitonin level dropped to 23 pg/mL postoperatively. Genetic testing was performed to assess for Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 (MEN2), and although her result was indeterminate, a RET mutation was not identified.

Case 3

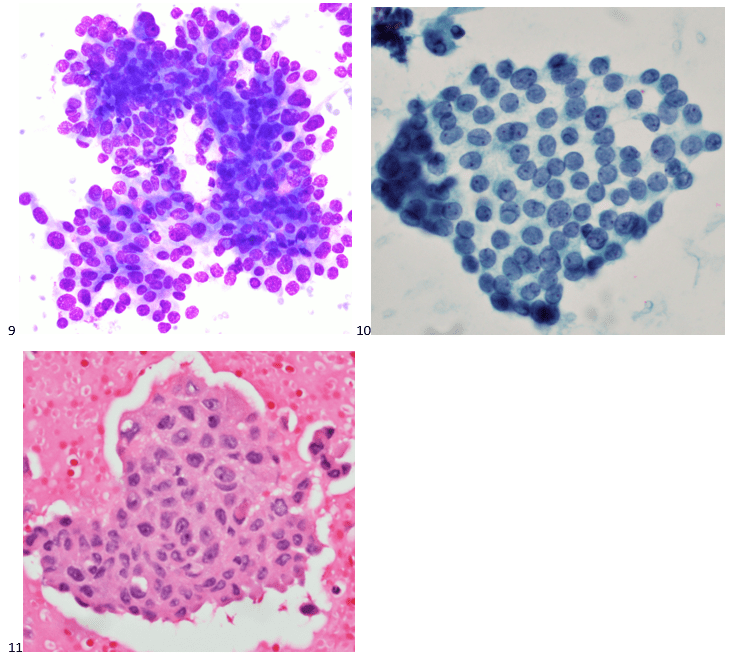

A 67-year-old male with no pertinent medical history presented to the endocrinology clinic after his primary care physician identified a large lump in the patient’s neck. A 7.0 cm hypoechoic right thyroid mass with macrocalcifications was noted on ultrasound imaging. The patient was referred to diagnostic imaging for a thyroid FNA. The smears and cell block section are depicted below. While the papillary formation of Image 9 is not evident on the pap-stained slide (Image 10), the nuclear grooves and pseudoinclusions along with irregular nuclear membranes and powdery chromatin are highlighted. A separate needle pass was collected for molecular testing, which revealed a BRAF V600E mutation in the tumor cells.

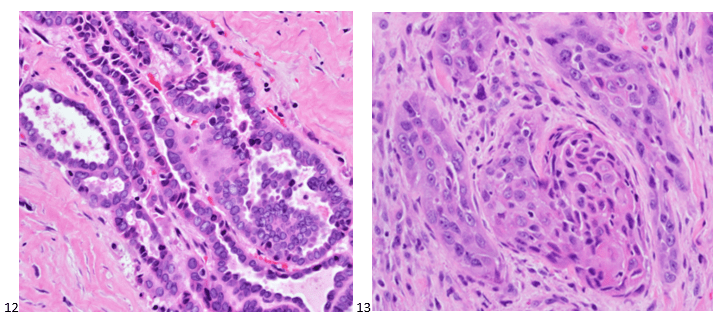

Two weeks after the FNA diagnosis, the patient was scheduled for a partial thyroidectomy of the right lobe. While 60% of the mass demonstrated well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma (Image 12), 40% of the tumor contained poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma with squamous features (Image 13). No sarcomatous components or giant tumor cells were identified. Carcinoma with squamous features invaded into the surrounding tissue, strap muscle, thymus, and right paratracheal lymph node. Interestingly, the right-sided levels 3 and 4 lymph nodes contained predominantly well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma with rare foci of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma with squamous differentiation.

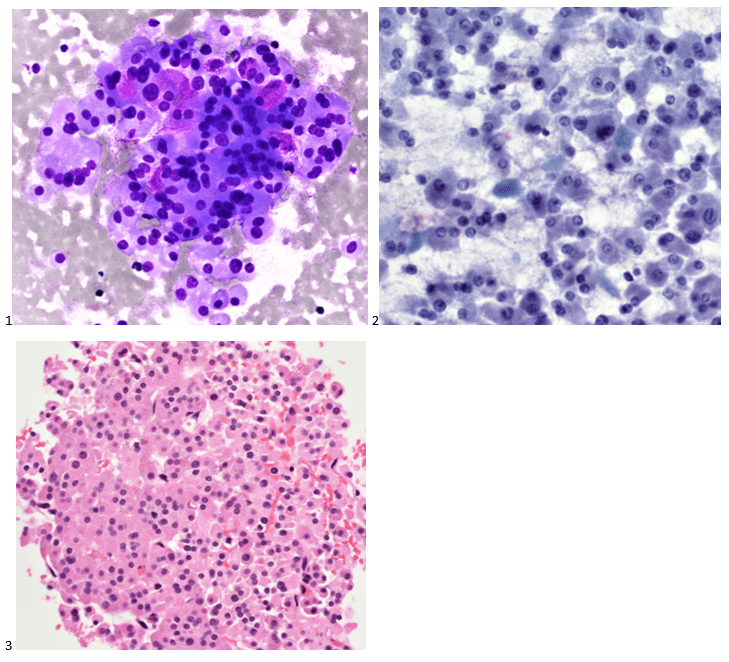

Five months after the excision, the patient developed a left-sided pleural effusion. A diagnostic thoracentesis was performed and metastatic thyroid carcinoma was identified. Immunostains performed on the cell block slides with adequate controls show that the tumor cells are positive for PAX8, and negative for TTF-1, and thyroglobulin. The findings support the diagnosis. While patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma tend to have better disease-free survival rates, the poorly differentiated tumor was difficult to control and eventually resulted in widespread metastasis.

Cytology diagnosis: Papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Pathology diagnosis: Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma with squamous features in a background of well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Case 4

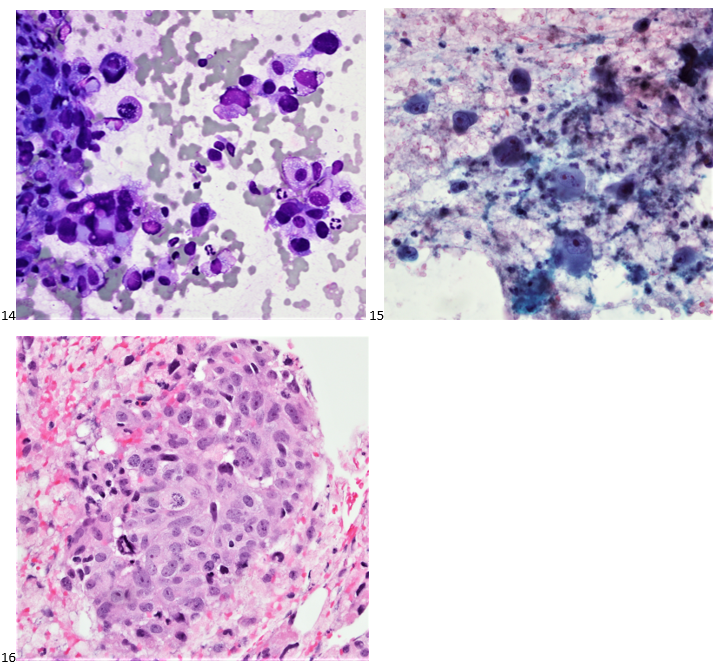

A 73-year-old female presented with a rapidly growing and painful thyroid mass that measured 8 cm on imaging. Originating from the right lobe, multiple needle passes targeted various areas of the mass via ultrasound-guidance. The smears and cell block section are presented below. Smears (Images 14-15) feature pleomorphic nuclei in a background of inflammation and necrosis. The cell block section (Image 16) demonstrates increased mitotic figures and neutrophils.

We performed immunocytochemical stains on paraffin sections of the cell block. Tumor cells how positive staining for p53, focal staining for cyclin D1, and negative staining for AE1/AE3, thyroglobulin, and BCL-2. Rare tumor cells show staining for TTF-1. The proliferation index by Ki-67 immunostaining is approximately 70%.

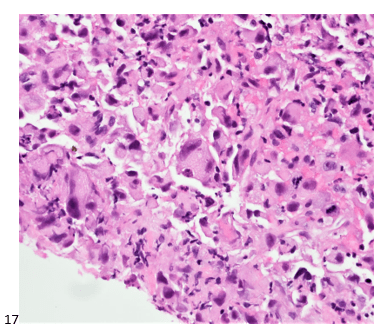

While not a standard procedure for thyroid specimens, core biopsies (Image 17) were also obtained from this mass.

Molecular testing on the core biopsy sample identified a high mutation burden, with the tissue harboring both TP53-inactivating and TERT promoter mutations. Imaging demonstrated widespread metastasis, and this patient did not survive the extensiveness of her disease.

Cytology Diagnosis: Undifferentiated (anaplastic) thyroid carcinoma.

Pathology Diagnosis: High-grade carcinoma consistent with anaplastic carcinoma (interchangeable diagnoses).

That’s enough for our classic thyroid cases. Stay tuned for the second edition featuring thyroid FNAs with unsuspecting findings!

-Taryn Waraksa-Deutsch, MS, SCT(ASCP)CM, CT(IAC), has worked as a cytotechnologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since earning her master’s degree from Thomas Jefferson University in 2014. She is an ASCP board-certified Specialist in Cytotechnology with an additional certification by the International Academy of Cytology (IAC). She is also a 2020 ASCP 40 Under Forty Honoree.