Case History

A 47-year-old male originally from Dominican Republic, with a recent diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and diffused large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), was admitted because of seizures and a rapidly increasing left neck mass. MRI of the brain showed a 2.5 x 1.2 cm (about 0.47 in) lesion in the left inferior parietal lobe – (1.4×0.7cm) in the right frontal lobe, plus multiple scattered bilateral lesions. Because of this, he underwent craniotomy/craniectomy for possible resection. A biopsy was taken from the right temple lesion and sent for aerobic, anaerobic, fungal, mycobacterial culture, surgical pathology and Toxoplasma PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction).

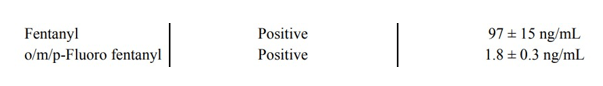

Gram stains, KOH prep, acid-fast stains, and Toxoplasma PCR of the tissue were all negative. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures did not show any growth.

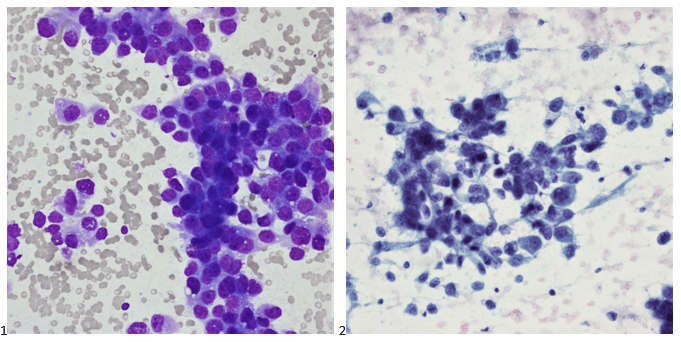

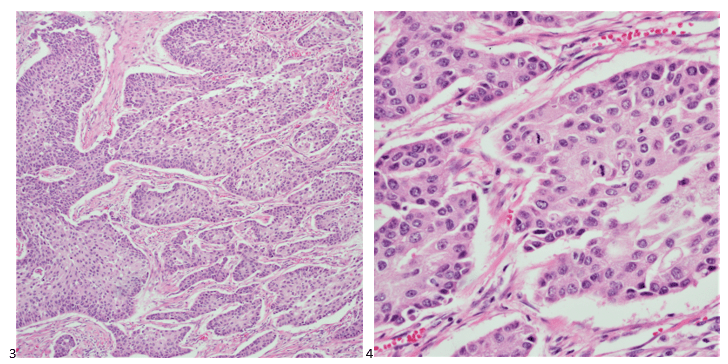

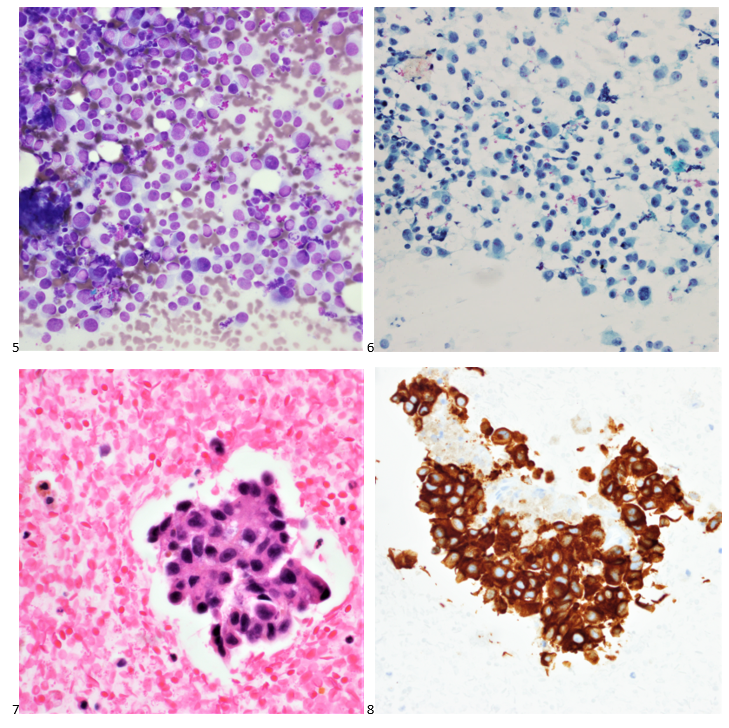

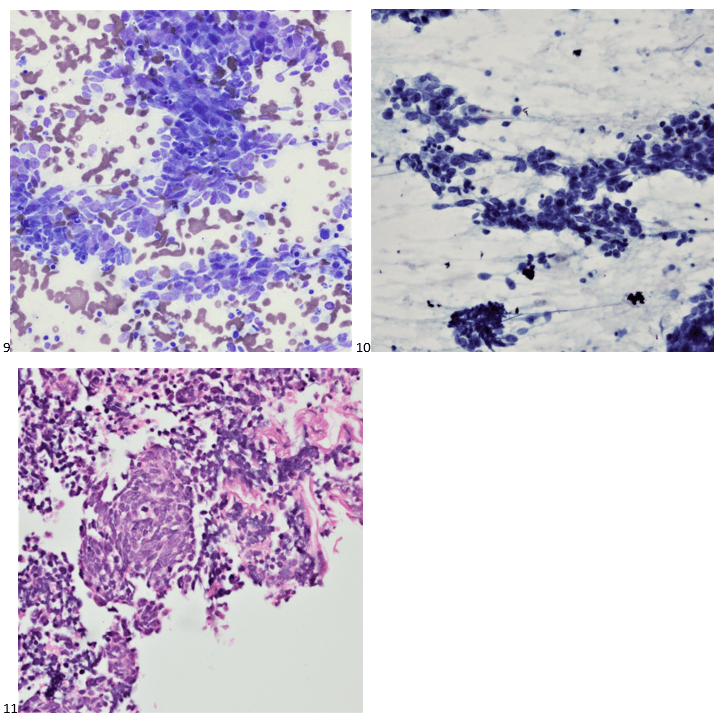

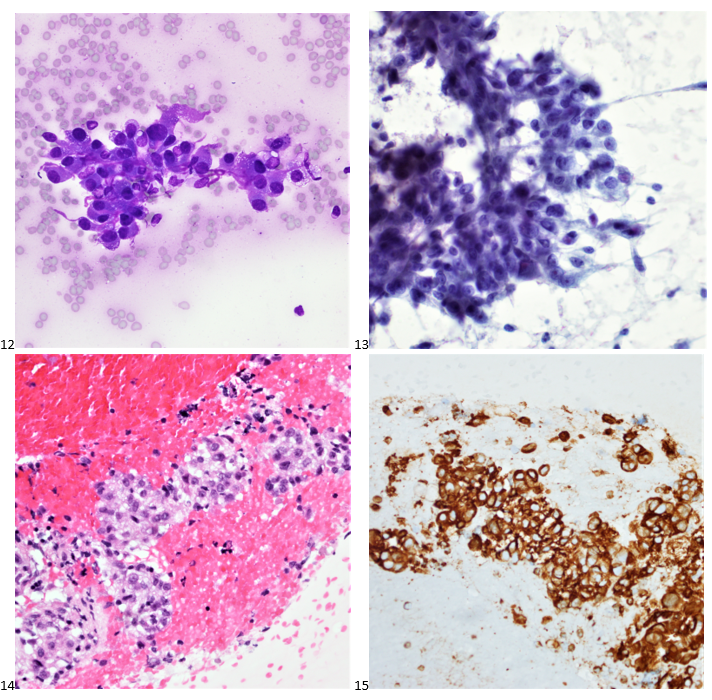

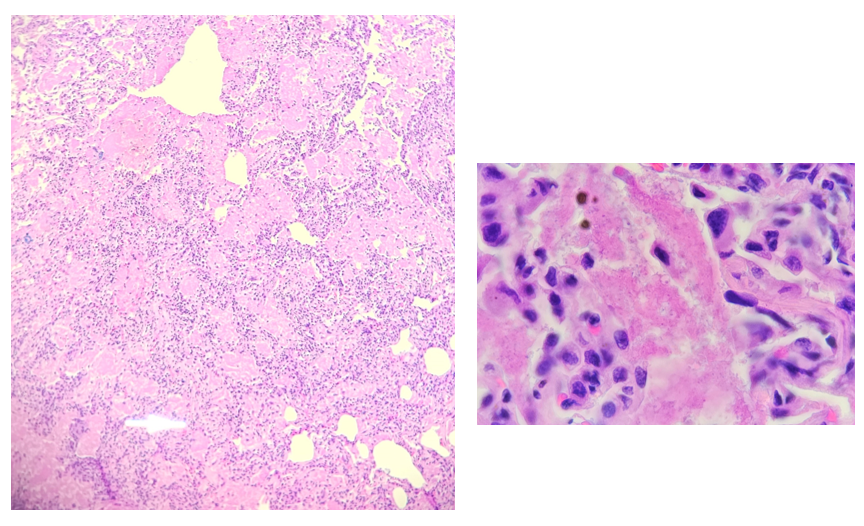

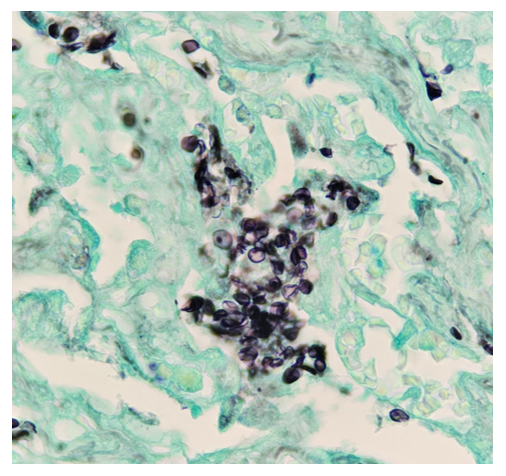

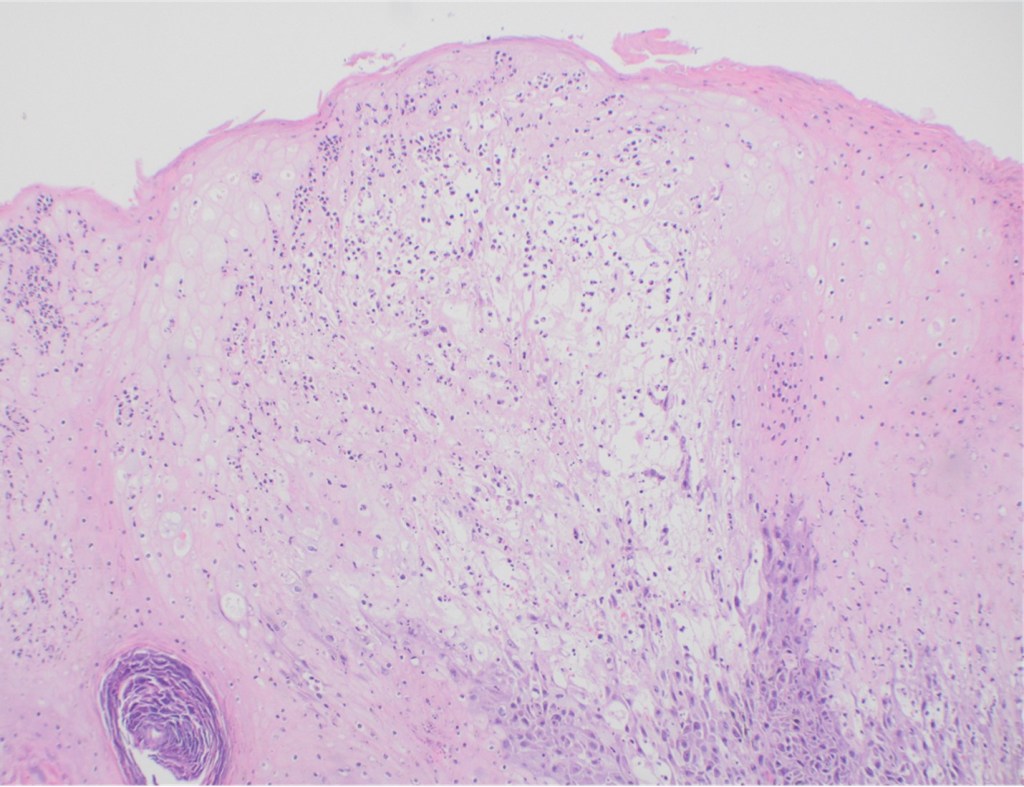

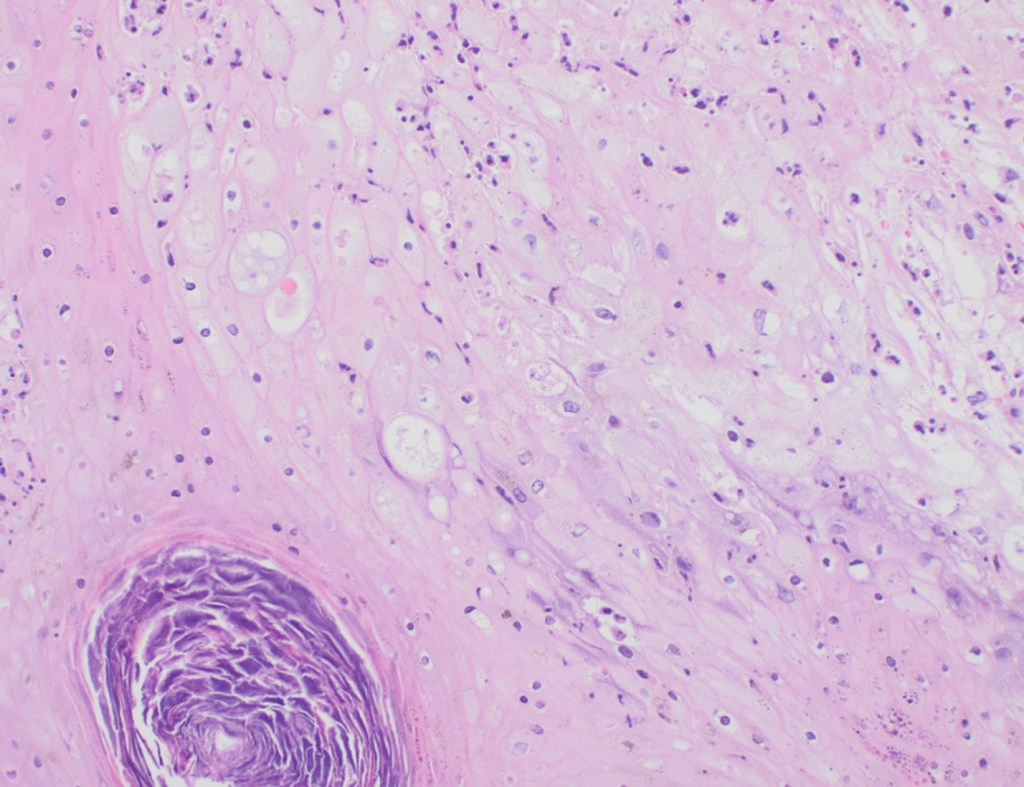

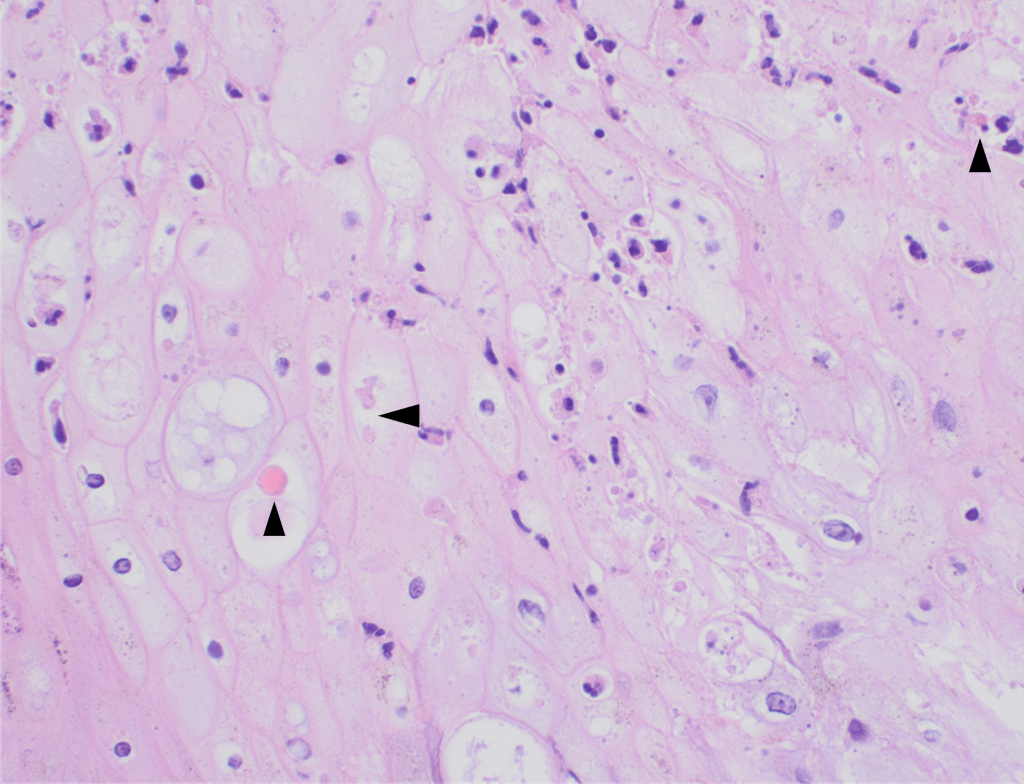

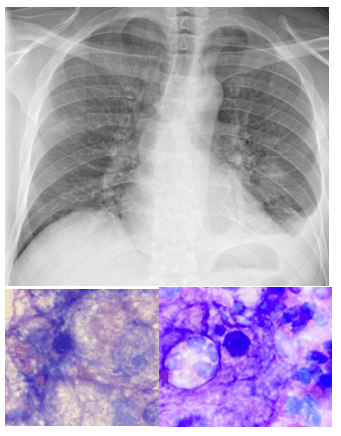

Histopathology slides (GMS and H&E stains in Fig A and B) show budding yeasts morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus. Mucicarmine stain was also positive. Lumber puncture was performed the next day and Cryptococcal antigen was positive, with a titer of 1:640. Interestingly, the CSF culture and Gram stain did not reveal any organisms.

Discussion

Among several species of Cryptococcus, C. neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii are pathogenic, with C. neoformans causing meningitis in immunocompromised patients worldwide whereas C. gattii has a preference for immunocompetent individuals.1 Cryptococcal disease remains a major opportunistic infection and a leading cause of mortality in patients infected with HIV in much of the developing world. Most HIV-related meningitis cases are caused by Cryptococcus neoformans.2

Cryptococci are found in soil, due to contamination with pigeon droppings. The infection occurs through inhalation, with or without symptoms of pneumonia, with subsequent dissemination to the central nervous system (CNS) via blood. Imaging findings are often unspecific or negative. CT or MRI examination of the central nervous system is performed to rule out alternative diagnoses. The diagnosis of ‘meningitis’ is made with a lumbar puncture, which typically shows lymphocytosis, an increased protein and decreased glucose concentration. Few neutrophil granulocytes are often found in CSF. This is likely because neutrophil migration is inhibited by specific polysaccharides that are part of the cryptococcal capsule.3

Cryptococci can be seen directly in the sediment of centrifuged CSF stained with India ink. The sensitivity and specificity of India ink is poor; therefore, CSF Gram stain and culture, multiplex meningitis/encephalitis PCR, and lateral flow antigen (LFA) tests have replaced the use of India ink. The cryptococcal lateral flow antigen test should be performed in CSF and serum, in addition to Multiplex ME PCR panel, and is a preferred test because of high sensitivity (93-100%) and specificity (93-98%).4

High organism burden at baseline (indicated by quantitative CSF culture or CSF antigen titre) and abnormal mental status are the most important predictors of death, while high opening pressures and a poor inflammatory response in the CSF have also been associated with poor outcome.5

On H&E it has the characteristic appearance ofencapsulated variably sized yeasts (2-20 microns) with thin walls which can be highlighted with the GMS stain. Although the presence of a capsule differentiates Cryptococcus from Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis with the H&E or mucicarmine stain, additional confirmation can be made with Fontana-Masson stainin the absence of capsules.6 Since both C.neoformans and C. gattii produce melanin, the pathology report by FM silver or H&E/GMS stain cannot further distinguish these two closely resembled species.

Occasionally, cryptococcal meningitis cases with sterile CSF culture and/or negative Cryptococcal CSF antigen are observed in HIV individuals, regardless of the CD4 counts.7,8 However, serum Cryptococcal antigen and blood culture may be positive in those individuals.7 In our case, the diagnosis of Cryptococcal meningitis was made by the pathology report and positive CSF Cryptococcal antigen.

-Fnu Sapna is a 2ndyear AP/CP pathology resident in the Department of Pathology at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, NY. She completed her Medical education at Chandka Medical College in Pakistan. Her interests are putting efforts to improve screening guidelines for diagnosis of preventable gynecological and breast cancers.

-Phyu Thwe, Ph.D, D(ABMM), MLS(ASCP)CM is Associate Director of Infectious Disease Testing Laboratory at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY. She completed her medical and public health microbiology fellowship in University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, TX. Her interests includes appropriate test utilization, diagnostic stewardship, development of molecular infectious disease testing, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis.