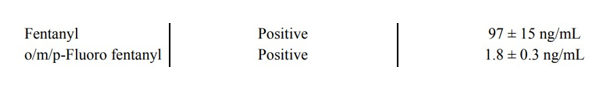

I was recently reviewing new toxicology reports from my pending autopsies, and came across a report with the following results:

Looking at this in isolation, it would be easy to assume this person died from an overdose. Even low levels of fentanyl can be dangerous to an opioid-naive individual – a level this high is rare. Then there’s the added presence of fluoro fentanyl, a fentanyl analog, which would seem to support the notion of an overdose. The problem with this assumption? This person died from blunt force trauma as a pedestrian struck by a car. He was, according to witness accounts, walking and talking right until the moment of impact. Autopsy had shown multiple blunt force injuries incompatible with life.

This situation illustrates some of the complexity of postmortem forensic toxicology. Despite methodology being nearly the same, toxicology in a forensic setting differs in many important ways from that performed in a clinical setting.

The first major difference occurs in the pre-analytical phase. The results of clinical testing may be used to alter therapy or make a diagnosis. However, forensic toxicology results are meant to be used in a court of law, meaning the chain of custody needs to be maintained. If there is no documentation of who touched the sample and when, the integrity of the specimen can be called into question and results may be impermissible.

Not all forensic toxicology is performed on deceased patients. Specimens may be taken from the living during evaluation of an alleged assault, driving under the influence, or for workplace monitoring. In autopsy specimens though, postmortem redistribution (PMR) is another pre-analytical factor to consider. After death the stomach, intestines, and liver can serve as a drug reservoir and passively transfer the drug to surrounding vasculature. Other organs can also act as reservoirs, depending on where the drug is concentrated in life. Drugs which are highly lipid-soluble and/or have a high volume of distribution will diffuse down their gradient from adipose tissue into the bloodstream – antidepressants are notorious for this, and elevated postmortem levels need to be interpreted with caution.

Autopsy specimens are also more varied in type and quality than typical clinical specimens. Vitreous fluid, bile, and liver tissue are commonly collected at autopsy, in addition to central (heart) and peripheral (femoral or subclavian) blood. Femoral blood vessels, being relatively isolated from PMR-causing drug reservoirs, are a preferred source of specimens. Decomposition or trauma can limit the types or quantity of specimens and may even alter results. After death, bacteria from the GI tract proliferate and can produce measurable levels of ethanol in the blood. Decomposition also produces beta-phenethylamine, which can trigger a ‘positive’ result for methamphetamine on ELISA-based tests.

The post-analytical phase of autopsy toxicology also poses unique challenges. Lawyers and law enforcement will sometimes ask what the ‘lethal level’ of a drug is, and they’re invariably disappointed by my response. While there are published ranges of toxicity and lethality for most drugs, these are only general guidelines. There is no absolute lethal blood level for prescription or illicit drugs. Opioid users develop tolerance, making them relatively immune to a dose which would kill an opioid-naive person. In the example of the pedestrian described above, he had a long history of heroin abuse and could therefore tolerate much higher levels than most. For stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine, there are no documented ‘safe’ levels as any amount could act as an arrhythmic agent. To add to the complexity, most overdose deaths involve multiple substances which may have synergistic effects and interactions that are difficult to parse.

Because of the reasons given above, the National Association of Medical Examiners still recommends full autopsy for possible overdoses. Deciding if a death was due to overdose is more complex than just reading a toxicology report – it requires interpretation and correlation with the autopsy findings and overall investigation.

References

D’Anna T, et al. The chain of custody in the era of modern forensics: from the classic procedures for gathering evidence for the new challenges related to digital data. Healthcare. 2023 Mar;11(5):634.

Davis GG, et al. National Association of Medical Examiners Position Paper: Recommendations for the Investigation, Diagnosis, and Certification of Deaths Related to Opioid Drugs. Acad Forensic Pathol 2013 3(1):77-81.

Pelissier-Alicot AL, et al. Mechanisms underlying postmortem redistribution of drugs: A review. J Anal Toxicol. 2003 Nov-Dec;27(8):533-44.