A 47 year old female presented to the ER with abdominal pain and obstructive jaundice. CT and MRI imaging confirmed a 9.7 cm complex pancreatic head and uncinate process mass that encases and obliterates the distal superior mesenteric vein, encases the superior mesenteric artery, abuts the aorta and IVC and extends into the aortocaval space, displacing the aforementioned structures. By definition, the presentation of this mass indicates locally advanced disease. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a next-day endoscopy and fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass with biliary stent placement.

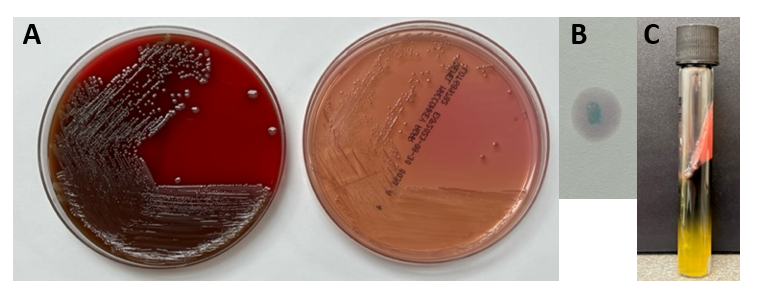

During the procedure, the cytologist made two smears from two separate passes. The two Diff-Quik-stained smears demonstrated scattered isolated atypical cells with vacuoles in the cytoplasm. The cytologist and pathologist agreed that the cells seen were atypical at best and were debating whether they could be lesional cells or macrophages and that it would be better to see a third smear. The third Diff-Quik smear showed the same cells but this time they were forming aggregates or clusters (Images 1-2). The pathology team deemed the third pass suggestive of tumor. The cytologist collected an additional two needle passes to be rinsed in a balanced salt solution for cell block preparation.

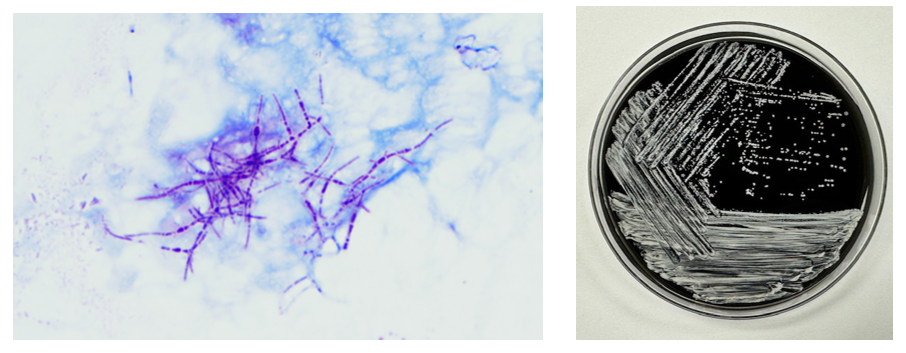

The next morning, the cytologist examined the Papanicolaou-stained slides. The same foamy or microvesicular cytoplasmic vacuoles identified on the Diff-Quik smears were also appreciated on the pap-stained slides (Image 3). There was almost a pink hue to the cytoplasm, which made us question a mucinous tumor. The nuclei were small-to-medium in size with irregular nuclear contours and eccentrically placed. Nucleoli were also appreciated within the tumor cells (Image 4). The H&E-stained cell block sections were beautiful, capturing the nesting architecture of the lesional cells identified on smears (Image 5).

The cytologist and pathologist were both confident that this could be a metastatic renal cell carcinoma, clear cell type. However, there was no evidence of a renal mass. Cancer does what cancer wants though, and to rule out renal cell carcinoma, the pathologist ordered PAX-8 and RCC immunohistochemical (IHC) stains. The tumor cells for both stains came back negative. Back to the drawing board. What if this is an odd presentation of a mucinous cystic neoplasm and these vacuoles are just mucin or a serous cystic neoplasm with glycogen vacuoles? Both mucicarmine and PAS (with and without diastase) were negative, ruling out both neoplasms, respectively. The pathologist and cytologist reviewed the clinical history and imaging. It seems like the only evidence of disease is stemming from the pancreatic mass with moderate lymphadenopathy. At this point, our job is to rule out every primary pancreatic tumor and get this woman an accurate diagnosis so she can 1) get peace of mind, 2) move onto surgery and adjuvant therapy, and 3) finally relieve her excruciating pain.

Let the panel ordering commence! We performed IHC stains on paraffin sections of the cell block with proper positive and negative controls. The tumor cells showed positive staining for AE1/AE3, CK19, CD56, synaptophysin (Image 6), chromogranin (weak), and E-cadherin, membranous staining (but no nuclear staining) for beta-catenin, focal staining for CK7, vimentin, and pCEA, very focal staining (rare cells) for CA19.9, and CD10. In addition to PAX-8 and RCC, the tumor cells showed negative staining for PR and S100. Proliferative index by the Ki-67 immunostain was approximately 2%.

Final diagnosis: Low-grade non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET/panNET) with clear cell features.

Had the tumor cells been positive for PR and negative for E-cadherin and chromogranin, a solid pseudopapillary neoplasm may have been in the differential. Negative PAS with diastase also helped to eliminate acinar cell carcinoma from the list of primary pancreatic tumors. It is worth mentioning that the clear cell variant of pNET/panNET is very unusual and may be associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

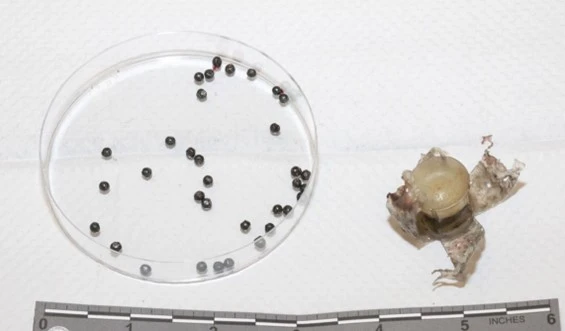

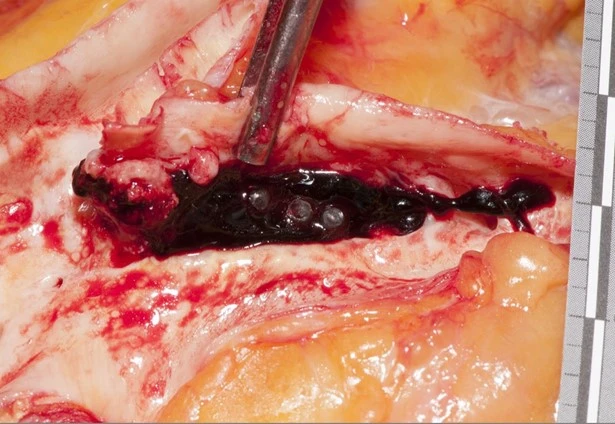

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy which revealed metastatic disease. As her symptoms progressively worsened over the next year, the patient decided, using a shared decision-making model with her medical oncologist, to pursue adjuvant therapy. CAPTEM (capecitabine and temozolomide) combined therapy was administered in the setting of progressive metastatic disease. Two years after the initial diagnosis and one years after the initiation of CAPTEM therapy, the patient received 2000 cGy of palliative radiation to the pancreatic mass. While this helped to reduce the disease burden within the primary site, extensive metastasis was noted including an obstructive duodenal mass and multiple liver lesions. Forcep biopsies of the duodenum and both FNAs and core biopsies of the liver demonstrated the same clear cell features of the original tumor, however, the Ki-67 proliferation index increased to 5%, which is consistent with an intermediate or grade 2 (G2) pNET. The patient developed uncontrolled bleeding and subsequently severe anemia and went on hospice. Within a matter of weeks after stabilizing her hemoglobin, the patient came off of hospice and began treatment with Lutathera, a radioligand therapy or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) which targets cells with somatostatin receptors. This therapy kept her relatively stable for an additional two years, but imaging demonstrated further progression on PRRT so an mTOR inhibitor was introduced to reduce the disease burden.

The beauty of oncology is that new therapies and advancements are always being developed and released, often improving the patient’s longevity and/or quality of life. The beauty of pathology is that the diagnosis is not always clear, but using the ever-expanding diagnostic and prognostic tools available to us can help us give the patient an answer and guide future treatments.

-Taryn Waraksa-Deutsch, MS, SCT(ASCP)CM, CT(IAC), has worked as a cytotechnologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since earning her master’s degree from Thomas Jefferson University in 2014. She is an ASCP board-certified Specialist in Cytotechnology with an additional certification by the International Academy of Cytology (IAC). She is also a 2020 ASCP 40 Under Forty Honoree.