Case History

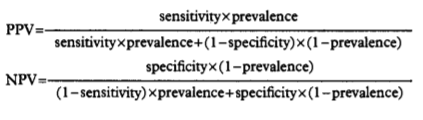

A 52-year-old man with multiple medical issues including a history of end stage renal disease on hemodialysis, chronic pancreatitis status post distal pancreatectomy, intravenous drug use through dialysis catheter, and multiple types of bacteremia presented with chills and abdominal pain. Labs on admission included a white blood cell count of 28.64 k/cmm, hemoglobin 8.8 g/dL, and platelets 581 K. He was diagnosed with a pancreatitis flare and admitted for pain management, with further labs drawn. After one day, he felt much better and was discharged with a pending blood culture to follow up on. At 61 hours, one bottle flagged positive with yeast seen on gram stain.

Laboratory findings

The organism was identified as Cryptococcus laurentii via MALDI-ToF MS. A follow-up fungal culture was negative, however, repeat blood culture grew Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. His tunneled catheter was removed, and two days later the patient required urgent interventional radiology access for dialysis. He completed a two-week course of ceftazidime and was discharged.

Discussion

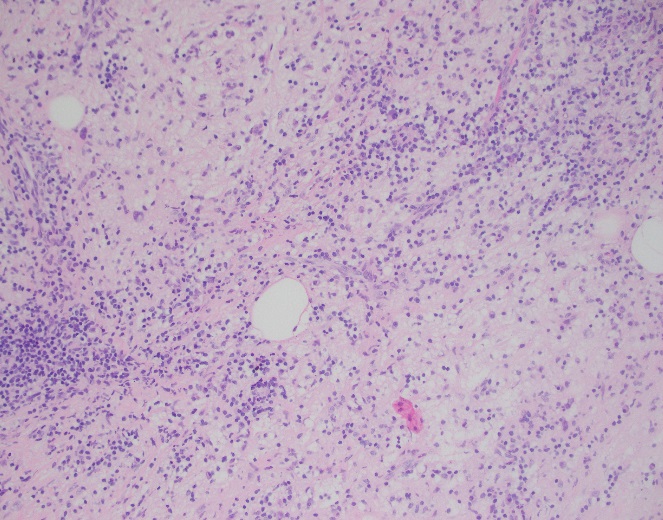

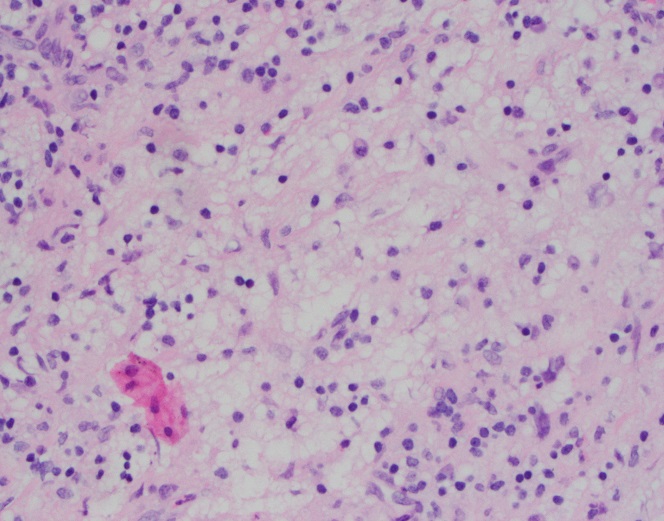

Cryptococcus laurentii is a very rare fungal pathogen. It is a psychrophilic organism, growing ideally at 15 °C, and is the most common yeast found in tundra.1 Major reservoirs include soil, food, and pigeon excrement.2 C. laurentii usually causes infection in immunocompromised hosts, although rare incidents of infection in immunocompetent patients have been reported. Reported manifestations have included fungemia, meningitis, peritonitis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, keratitis, and skin infection.3

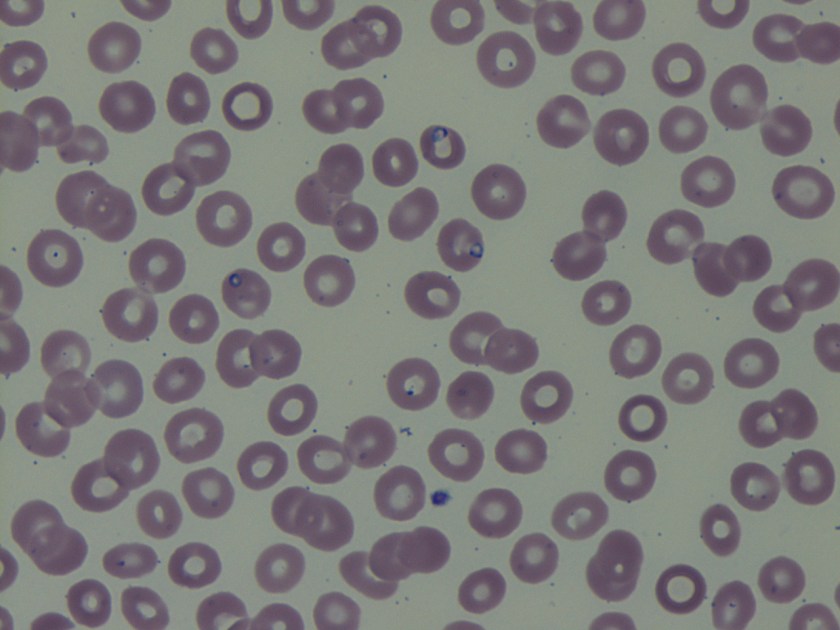

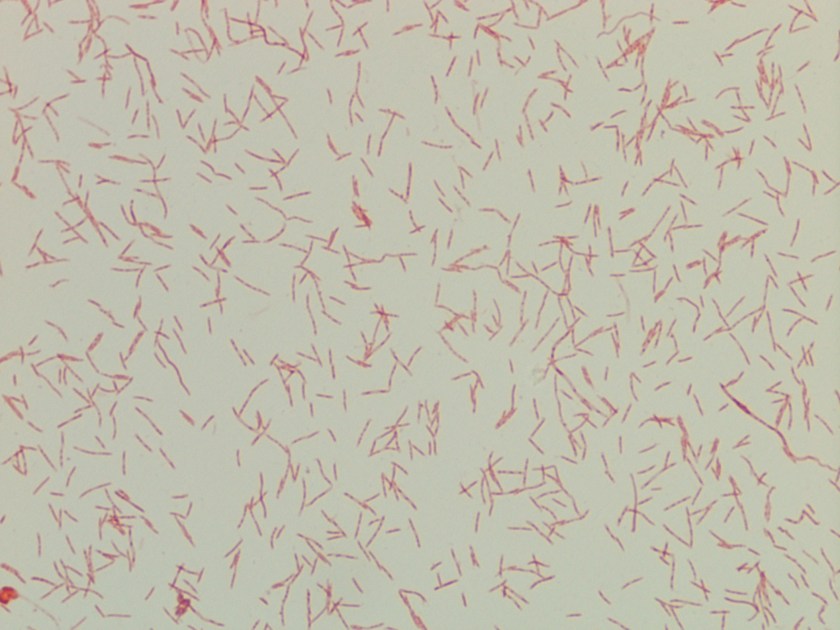

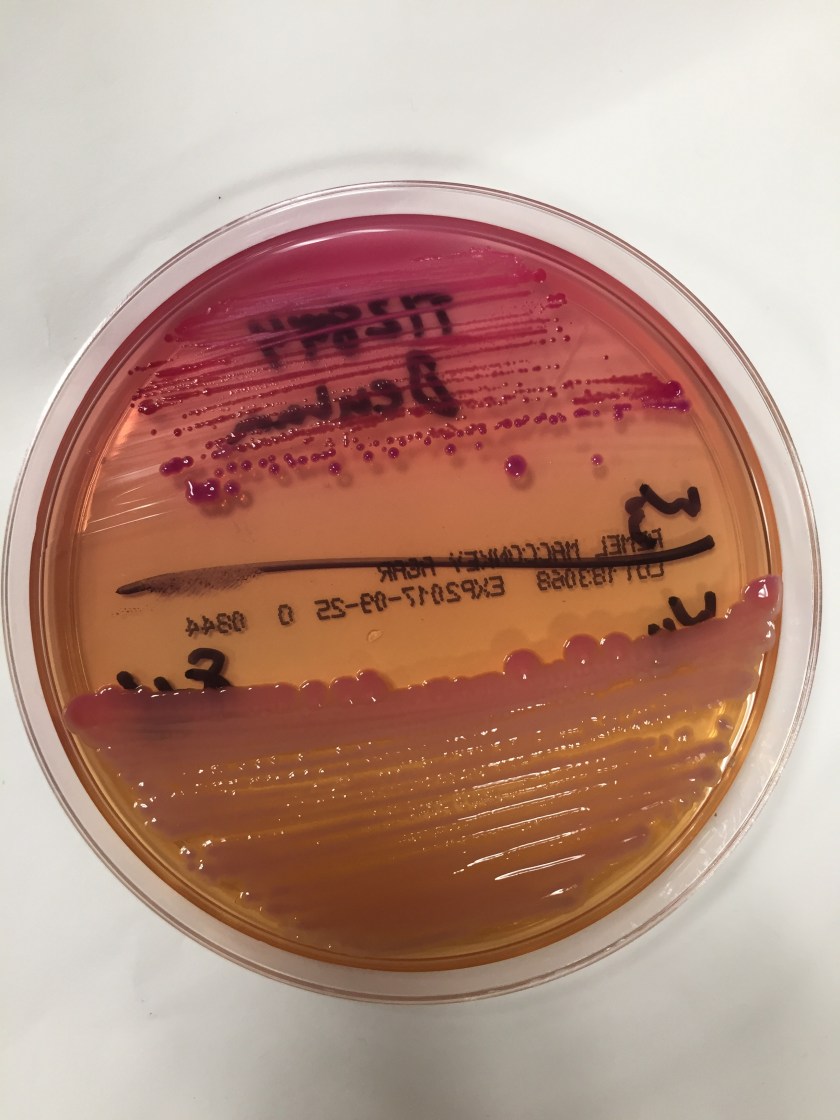

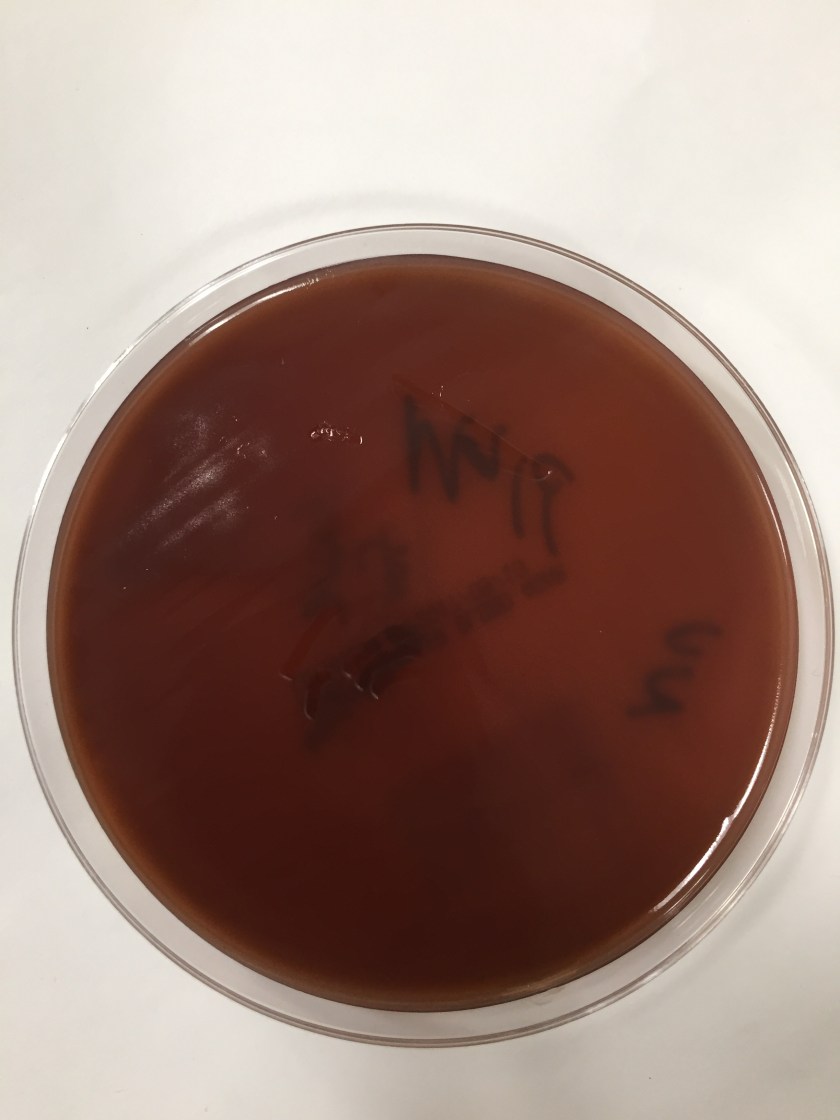

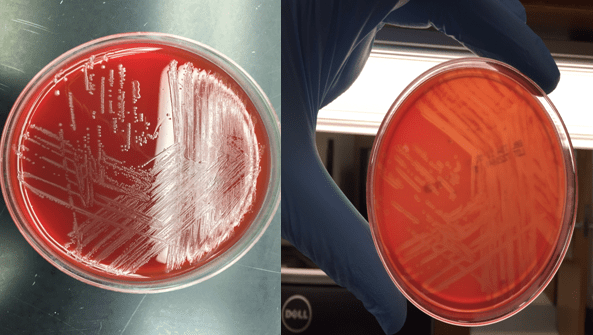

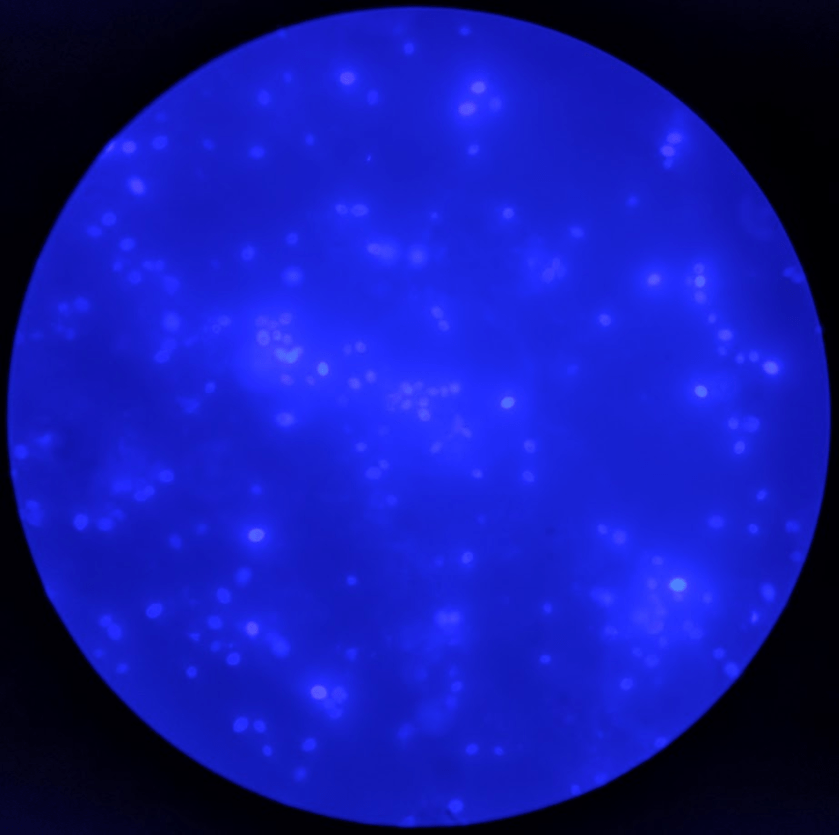

Cryptococcus laurentii is a urease-positive organism. Gram stain shows large budding yeasts without hyphae. The yeast grows on routine agar as whitish-yellow creamy colonies and on birdseed agar as whitish or greenish colonies. Staining with calcofluor highlights encapsulated yeast forms. Molecular diagnosis can be accomplished by ribosomal RNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer and D1/D2 regions. Treatment in most cases has been with fluconazole, although in one case of peritoneal dialysis catheter-related peritonitis, voriconazole was used due to low fluconazole susceptibility.4

References

- Molina-Leyva A, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Leyva-Garcia A, Husein-Elahmed H. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in an immunocompetent child. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17(12). doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.04.017.

- Johnson, L. B., Bradley, S. F. and Kauffman, C. A. Fungaemia due to Cryptococcus laurentii and a review of non-neoformans cryptococcaemia. Mycoses. 1998;41: 277–280. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00338.x

- Furman-Kuklińska K, Naumnik B, Myśliwiec M. Fungaemia due to Cryptococcus laurentii as a complication of immunosuppressive therapy – a case report. Advances in Medical Sciences. 2009;54(1). doi:10.2478/v10039-009-0014-7.

- Asano M, Mizutani M, Nagahara Y, et al. Successful Treatment of Cryptococcus laurentii Peritonitis in a Patient on Peritoneal Dialysis. Internal Medicine. 2015;54(8):941-944. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3586.

-Prajesh Adhikari, MD is a 3rd year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

-Christi Wojewoda, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and an Associate Professor at the University of Vermont.