Case History

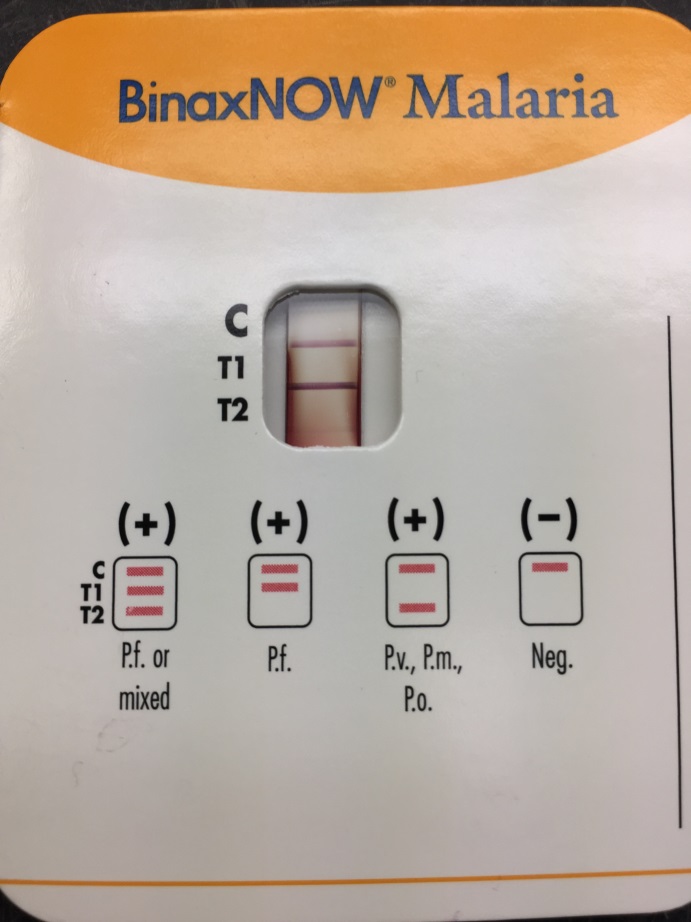

An 89-year-old gentleman presented with a cough, subjective fever, and potential wound infection on his forehead. He has a past medical history notable for hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, chronic congestive heart failure, past STEMI, history of gastric lymphoma, diabetes, Parkinson disease, and stage III chronic kidney disease. Two months prior to presentation, he fell down the steps of his apartment and suffered a laceration of his forehead that ultimately required surgical repair. He was discharged home with wound care instructions. He was doing relatively well up to 5 days prior to presentation when he started to develop a small, soft, erythematous lesion on his forehead with swelling and non-purulent appearing serous drainage at the site of repair. After it persisted, he presented to the emergency department where he underwent a small incision and drainage. A specimen was collected in a sterile syringe and sent to the microbiology laboratory for culture.

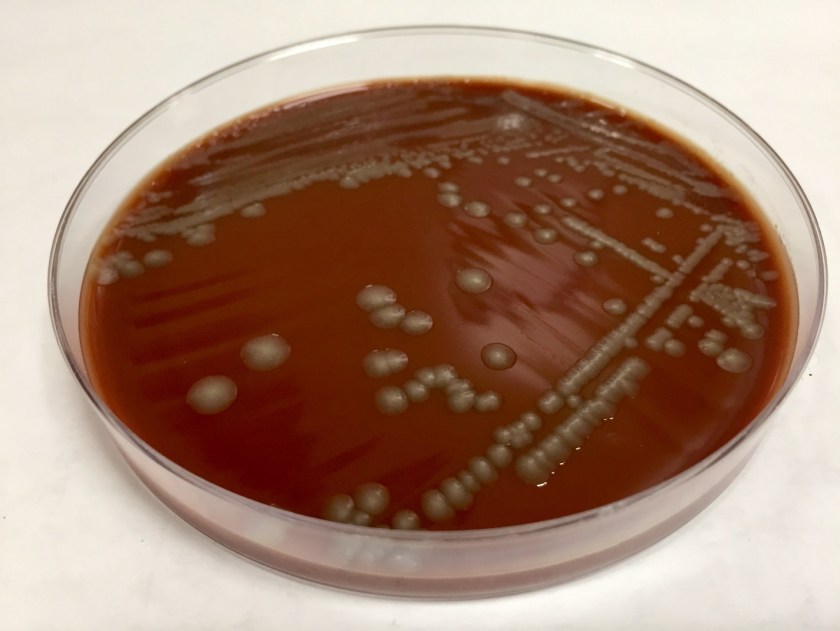

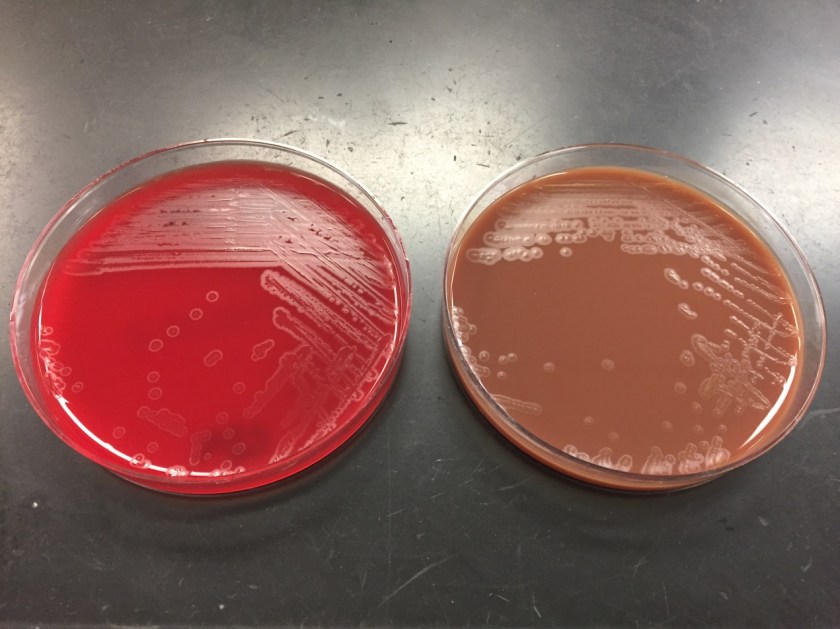

The organism was confirmed as Nocardia abscessus/asitica by a reference laboratory.

Discussion

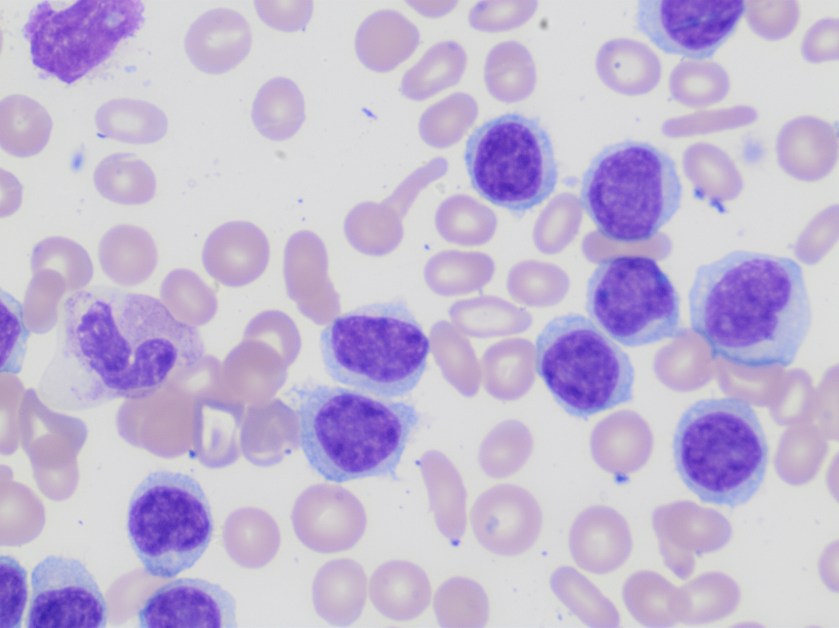

Nocardia is a genus of aerobic, weakly Gram-positive, catalase-positive, rod shaped bacteria that are modified acid-fast and form beaded branching filaments. They grow slowly on commonly used nonselective culture media, with colonies becoming evident in 3-5 days, and have the ability to grow in a wide temperature range. Colony morphology is variable, with colors ranging from white to orange and texture ranging from smooth to chalky. They are saprophytic organisms that are commonly found in soil, organic matter, and in the oropharynx as normal flora. Virulence factors for Nocardia include catalase, superoxide dismutase, and cord factor. Cord factor prevents lysosomal fusion with the phagosome, thus inhibiting phagocytosis by macrophages.

There are more than 80 species of Nocardia causing various forms of human disease, the most pathogenic of which are: N. asteroides, N.braziliensis, N.caviae, N.nova and N.abscesses. Symptoms can range from a localized lung or cutaneous infection to disseminated disease. Most infections involve the lung initially following inhalation of the organisms which commonly spread to extrapulmonary sites with the disease being more severe and likely to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients. In addition, the skin can be a site of primary infection through traumatic inoculation in immunocompetent patients.

Primary cutaneous infections occur in 5% of cases and manifest in one of the following ways: lymphocutaneous infection, mycetoma, superficial cellulitis, or localized abscesses. The most commonly involved sites for cutaneous infections are the extremities, though infection can affect any area, including the head and neck.

Treatment for primary cutaneous nocardiosis includes antimicrobial therapy and surgical irrigation and drainage when appropriate. Though antibiotic therapy is recommended, spontaneous resolution can occur without treatment. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used most frequently for nocardiosis with the usual duration of therapy being 2-3 months in those cutaneous disease.

References

- Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: Updates and Clinical Overview. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012;87(4):403-407. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.016.

- Vijay Kumar GS, Mahale RP, Rajeshwari KG, Rajani R, Shankaregowda R. Primary facial cutaneous nocardiosis in a HIV patient and review of cutaneous nocardiosis in India. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;32(1):40-43. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.81254.

- Lee TG, Jin WJ, Jeong WS, et al. Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis Caused by Nocardia takedensis. Annals of Dermatology. 2017;29(4):471-475. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.4.471.

- Outhred, A.C., Watts, M.R., Chen, S.CA. et al. Nocardia Infections of the Face and Neck. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2011 Apr;13(2):132-40. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0165-0.

-Clayton LaValley, MD is a 2nd year anatomic and clinical pathology resident at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

-Christi Wojewoda, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and an Associate Professor at the University of Vermont.