Case History

An 80 year old man presented with rapid onset of cervical adenopathy over a period of few months. The largest lymph node measuring 6 cm was biopsied and sent for histopathological evaluation.

Biopsy Findings

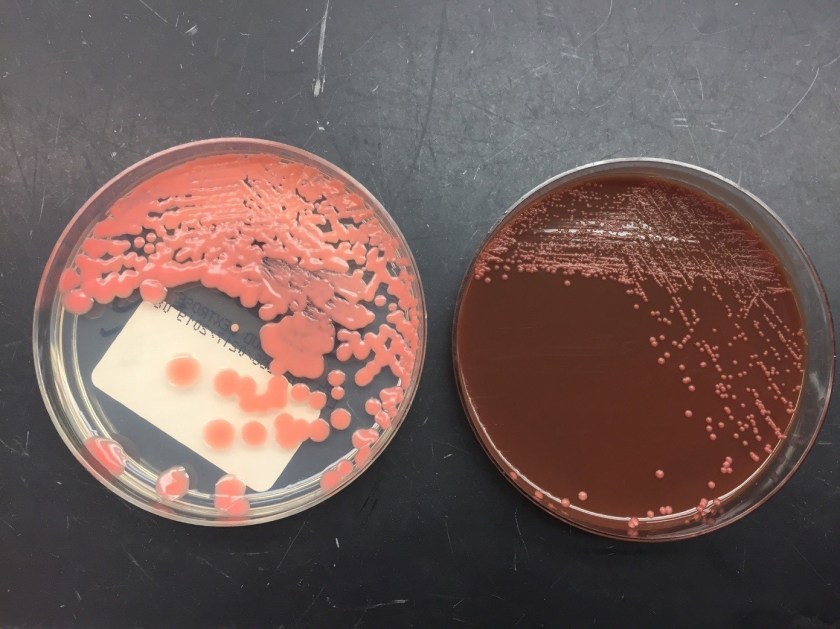

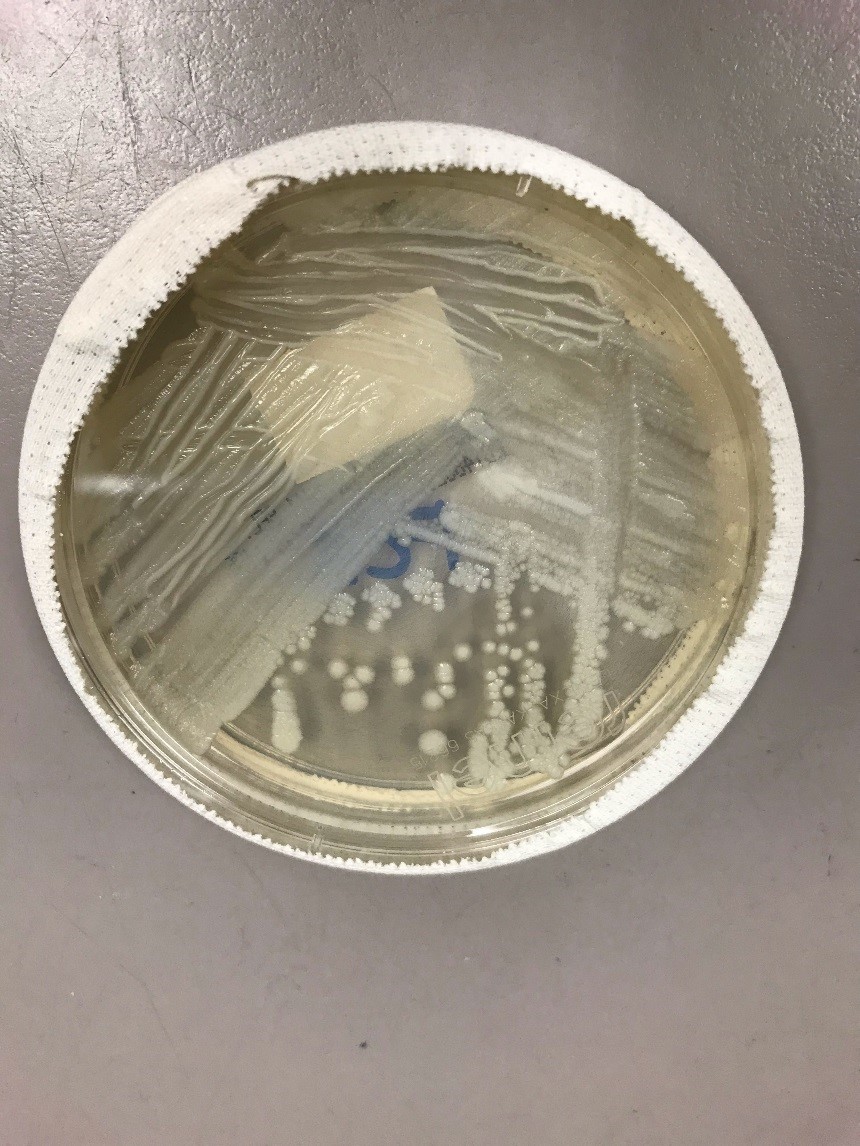

Sections from the lymph node showed effacement of the lymph node architecture by a fairly monotonous population of medium to large sized lymphoid cells arranged in vague nodular pattern. Focally, a starry sky pattern was observed. The cells were 1.5-2 times the size of an RBC, with high N:C ratio, irregular angulated nuclei and small nucleoli. A high mitotic rate of 2-3 mitoses/hpf was seen.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical stains showed that the lymphoma cells were positive for CD20, CD5, SOX-11, and negative for Cyclin D1, CD10, CD23, CD30, BCL-1, and BCL-6. Ki67 index was about 70%.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of Mantle cell lymphoma, pleomorphic variant was made.

Discussion

Mantle cell lymphoma is a peripheral B cell lymphoma, occurring in middle aged or older adults, with a male: female ratio of 7:1. Although Cyclin D1 expression is considered a hallmark of mantle cell lymphoma, yet about 7% cases are known to be Cyclin D1 negative. In these cases, morphological features and SOX-11 positivity helps in establishing a definitive diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

In the assessment of morphological features of lymphoma, the cell size is an important starting point. In this case, the lymphoma cells ranged from medium to large sized. The following differential diagnoses were considered:

- Burkitt lymphoma

This case showed a “starry sky” pattern focally. A medium sized population of cells, high mitotic rate and a high Ki67 index (70%) favoured a Burkitt lymphoma. However, although commonly seen in Burkitt lymphoma, a “starry sky” pattern is not specific for this type of lymphoma. Also, the lack of typical “squaring off” of nuclei, basophilic cytoplasmic rim were against the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma. The nuclei in this case showed 0-1 small nucleoli, unlike the typical basophilic 2-3 prominent nucleoli of Burkitt lymphoma. Moreover, Ki67 index, even though high was not enough for Burkitt lymphoma where it approaches 100%. The cells were negative for CD10 and Bcl-6, which are almost always found in a Burkitt lymphoma. Hence, a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma was ruled out.

- Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma

The presence of interspersed large cells with nucleoli, irregular nuclei, high mitotic rate, and a high Ki67 index with a history of very rapid enlargement of lymph node suggested a diagnosis of Diffuse Large B cell lymphoma. However, the scant cytoplasm, lack of bizarre cells, and absence of CD10, BCl-2, BCl-6 were against a diagnosis of DLBCL.

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma

A diagnosis of lymphoblastic lymphoma was favoured by the irregularly angulated nuclei, and presence of nucleoli. However, the cells of lymphoblastic lymphoma have a more delicate nuclear chromatin, higher mitotic rate as against the relatively condensed chromatin and the low to high variable mitotic rate of Mantle cell lymphoma. Also, lymphoblastic lymphomas are more commonly of the T cell subtype and occur commonly in younger individuals. In this case, B cell markers were positive (CD 20), and the patient was 80 year old, disfavouring a lymphoblastic lymphoma. The blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma is practically indistinguishable from lymphoblastic lymphoma, except that it is Tdt negative.

Cyclin D1 negativity in Mantle cell lymphoma

In the cases of Cyclin D1 negative mantle cell lymphomas, morphology plays a critical role in coming to a diagnosis of mantle cell lymphomas. In this case, points that favoured the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma were clinical features such as older age (80 years), and male gender, and morphological features such as a vaguely nodular pattern of growth, irregular nuclei, and 0-1 small nucleoli. Due to the presence of variably sized cells with distinct nucleoli, a pleomorphic variant was considered. Even though Cyclin D1 was found to be negative, the cells were positive for SOX-11.

SOX-11 is a transcription factor that is not normally expressed in B cells, but is sensitive and fairly specific for mantle cell lymphomas. It is important to note that SOX-11 is also positive in 25% Burkitt lymphoma, 100% lymphoblastic lymphoma, and 66% T-prolymphocytic leukemia. Herein lies the importance of recognising morphological features, as all of these lymphomas that may express SOX-11 were ruled on the basis of morphology. A more specific antibody, MRQ-58 may be used for greater specificity. The presence of SOX-11 is considered a specific biomarker for Cyclin-D1 negative mantle cell lymphomas. In these cases, there is upregulation of Cyclin D2 or D3 that may substitute for Cyclin D1 upregulation. But, immunohistochemical detection of Cyclin D2 or D3 is not helpful for establishing a diagnosis, as other lymphomas are commonly positive for these markers. Hence, it is important to perform SOX-11 immunohistochemistry to diagnose the Cyclin D1 negative variant of mantle cell lymphoma.

SOX-11 can be used not just for the diagnosis, but also for determining prognosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Indolent MCL usually lack SOX-11 expression. The pattern of SOX-11 staining has also been used a marker of prognosis. Cytoplasmic expression of MCl, seen in only a few cases was associated with a shorter survival as compared to the more common nuclear staining of SOX-11.

Conclusion

In this age, lymphoma diagnosis relies heavily on the use of immunohistochemical markers. However, this case highlights the importance of morphological features in diagnosing lymphomas with unusual immunohistochemical marker profile. Although, this case was negative for Cyclin D1, considered a hallmark of Mantle cell lymphoma, yet, the combination of morphological features with SOX-11 staining helped in clinching the diagnosis. To avoid a misdiagnosis, it would be prudent to perform SOX-11 staining in all lymphoma cases morphologically resembling MCL, but lacking Cyclin-D1.

-Swati Bhardwaj, MD has a special interest in surgical pathology and hematopathology. Follow her on Twitter at @Bhardwaj_swat.

–Kamran M. Mirza, MD, PhD, MLS(ASCP)CM is an Assistant Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Medical Education and Applied Health Sciences at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine and Parkinson School for Health Sciences and Public Health. A past top 5 honoree in ASCP’s Forty Under 40, Dr. Mirza was named to The Pathologist’s Power List of 2018 and placed #5 in the #PathPower List 2019. Follow him on twitter @kmirza.