Case Presentation

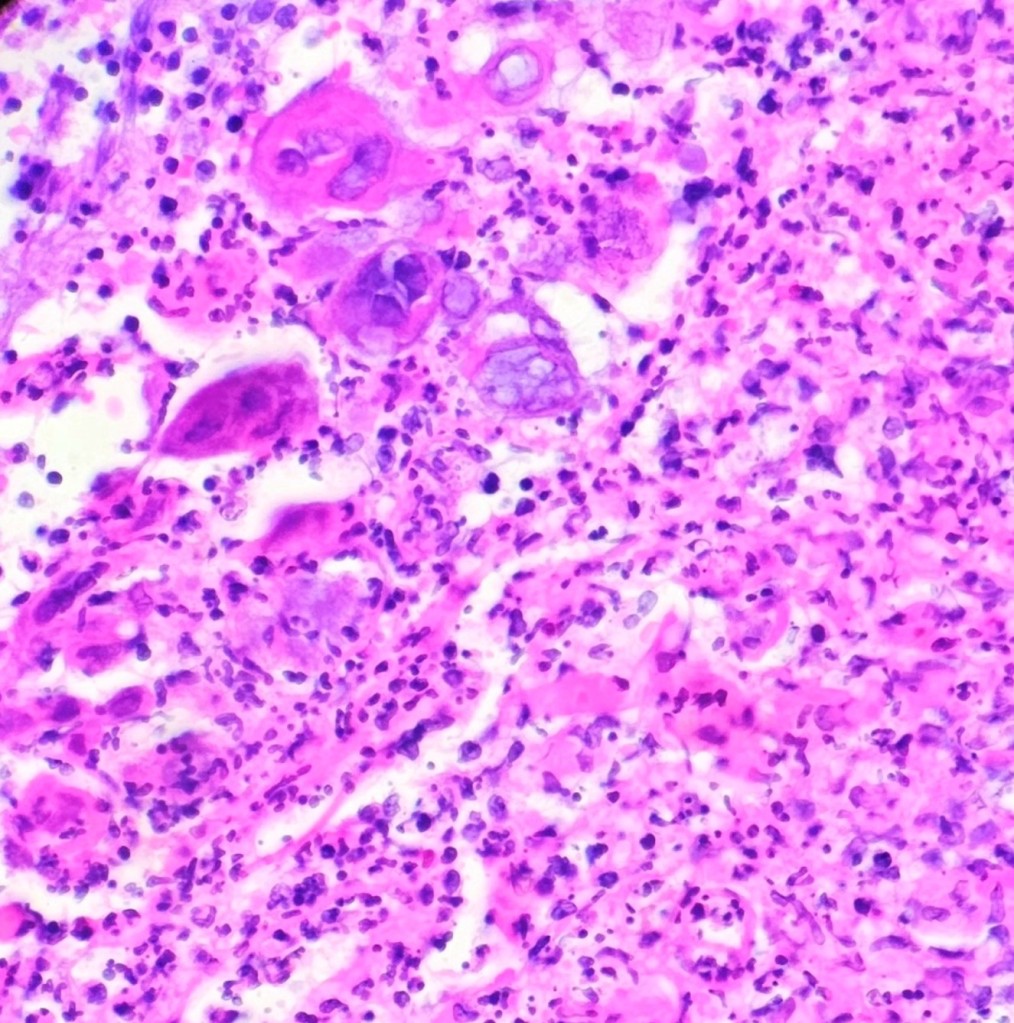

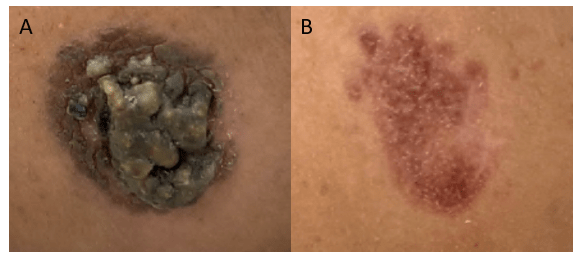

A young female presented to the dermatology clinic with a 6-month history of two worsening painless lesions on her nose and left cheek but was otherwise well. The lesions appeared while the patient was living in Ethiopia. On physical examination, two irregular, bumpy, yellow-brown lesions with surrounding erythematous papules (Figure 1A) were documented. Erythema and hyperpigmented patches surrounding the lesions were also noted. Both lesions were non-pruritic, and no other cutaneous or mucosal lesions were observed. A punch biopsy was obtained, and the lesion was sent for culture and histopathological review.

Laboratory Workup

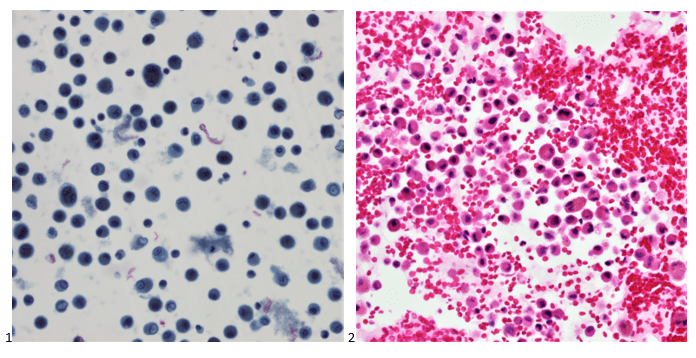

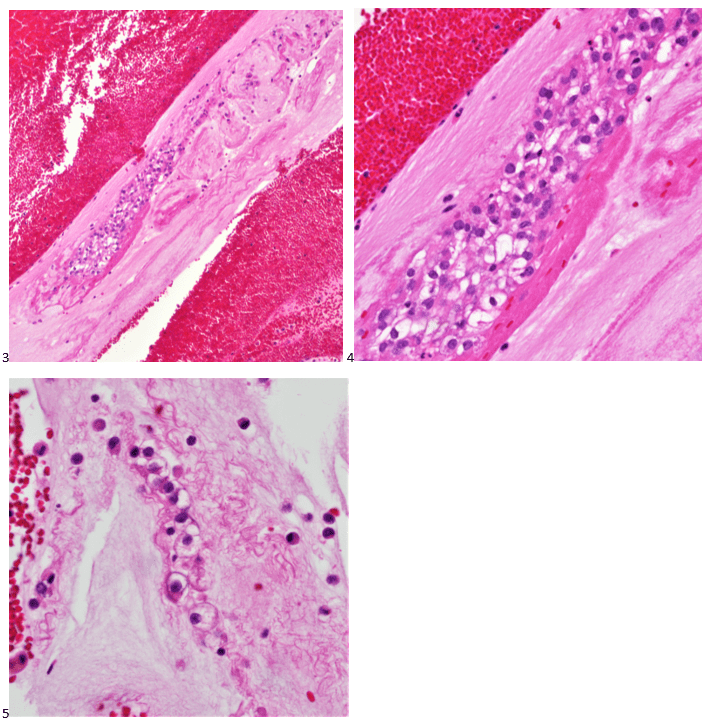

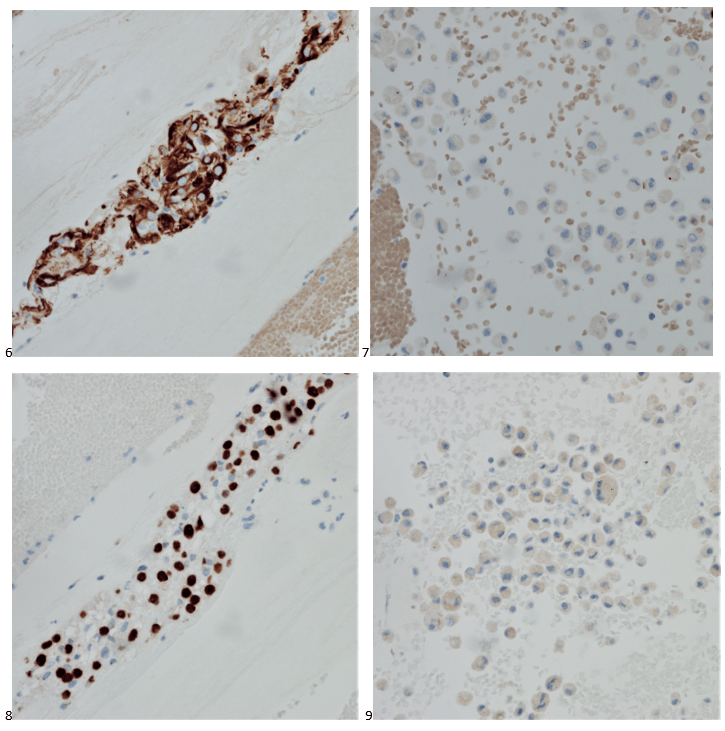

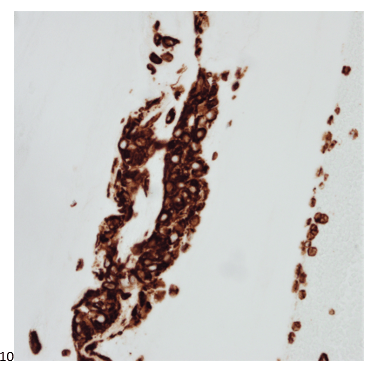

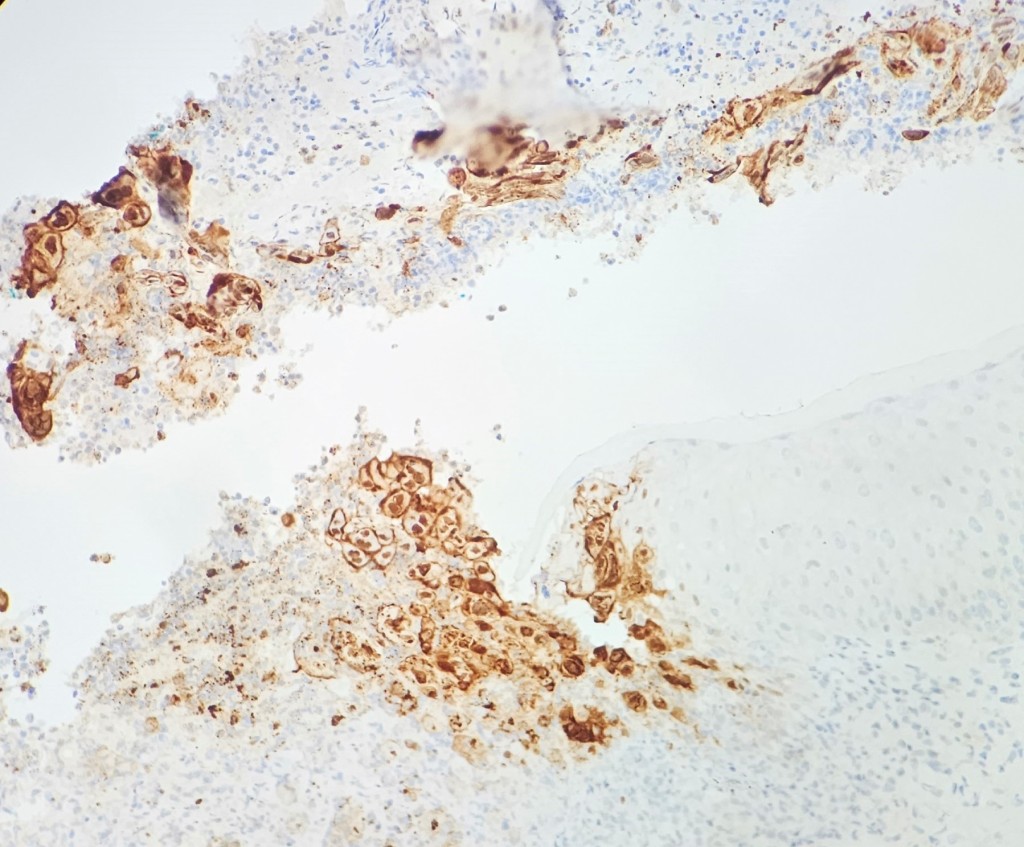

Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous intracellular and extracellular Leishmania sp. amastigotes (Figure 2A). The amastigotes measured 2–4 µm in diameter and were oval to round with a defined nucleus and kinetoplast (Figure 2B). A diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made, and the patient was referred to the infectious disease (ID) clinic for further evaluation and management. The patient was prescribed miltefosine for 28 days with planned follow up with ID, dermatology and ear nose and throat (ENT) groups. At a subsequent follow up visit two months later, her lesions have visibly improved, and she continues to be followed outpatient (Figure 1B).

Discussion

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne disease transmitted by sandflies. The disease is caused by obligate intracellular protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. Human infection is caused by 21 of 30 known species that infect mammals in the Eastern and Western hemispheres. Examples of common species causing disease in the Eastern hemisphere include the L. donovani complex, L. tropica, L. major, and L. aethiopica whereasthe most common species found in the Western hemisphere include L. mexicana complex, L. braziliensis, and the subgenus Viannia.1 The different species are morphologically indistinguishable and can only be differentiated by isoenzyme analysis, molecular methods, or monoclonal antibodies.2

Leishmaniasis presents as a diverse range of diseases depending on the species associated with the infection. Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL) is associated with L. donovani complex in the Eastern hemisphere and L. chagasi in the Western, can be life threatening, and is characterized by fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia.1 More than 90 percent of the world’s cases of VL are in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil.2 Worldwide, it has an estimated annual incidence of 0.7–1.0 million cases.3 The disease primarily affects the skin and can result in disfiguring lesions.

CL is the most common manifestation observed worldwide. L. major, L. tropica and L. aethiopica are common causes of CL in the East and L. braziliensis and L. mexicana are common causes of CL in the West.1 The clinical presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis can vary depending on the Leishmania species involved, the immune status of the host, and the local immune response at the site of infection. The incubation period of cutaneous leishmaniasis can range from several days to months, with disease presenting as solitary or multifocal lesions. Affected areas may be ulcerated or nodular.4 This patient’s presentation was more nodular in appearance. Additionally, L. braziliensis can cause mucocutaneous leishmaniasis frequently months to years after spontaneously healed CL, which can erode the nasal septum, palate, or other mucosal structures.2

Serological tests can detect the presence of antibodies against Leishmania but cannot be used as a surrogate for treatment success because antibodies can continue to circulate following successful treatment.5 Histopathological examination of a skin biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The presence of intracellular and extracellular amastigotes in a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate is highly suggestive of the disease.6 Treatment of leishmaniasis depends on the presentation and disease severity. Topical therapy, such as paromomycin ointment, can be used for CL. Systemic therapy (such as what this patient received) is indicated in the setting of immunosuppression, or if the lesions are large, multifocal, affect the joints, hands, or feet. Various antiparasitic agents are available for the treatment of leishmaniasis, including pentavalent antimonials. amphotericin B, miltefosine, and paromomycin.6 In some cases, surgical intervention may be required to remove larger ulcers or nodules.

References

1. Garcia, L. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 6th edition. “Leishmaniasis”. ASM Press. 2016. Chapter 27, p778-793.

2. CDC – DPDx – Leishmaniasis. Published January 18, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

3. Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):951-970. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2

4. Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(9):581-596. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70209-8

5. Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Updates in Diagnosis and Management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

6. Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, Al-Qubati Y, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: Differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(6):911-926; 927-928. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.014

–L. Jonathan He is a fourth year AP/CP resident at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas.

-Dominick Cavuoti, DO is a professor in the Department of Pathology who practices Medical Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Pathology and Cytology.

-Andrew Clark, PhD, D(ABMM) is an Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in the Department of Pathology, and Associate Director of the Clements University Hospital microbiology laboratory. He completed a CPEP-accredited postdoctoral fellowship in Medical and Public Health Microbiology at National Institutes of Health, and is interested in antimicrobial susceptibility and anaerobe pathophysiology.

-Clare McCormick-Baw, MD, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Microbiology at UT Southwestern in Dallas, Texas. She has a passion for teaching about laboratory medicine in general and the best uses of the microbiology lab in particular.