Case History

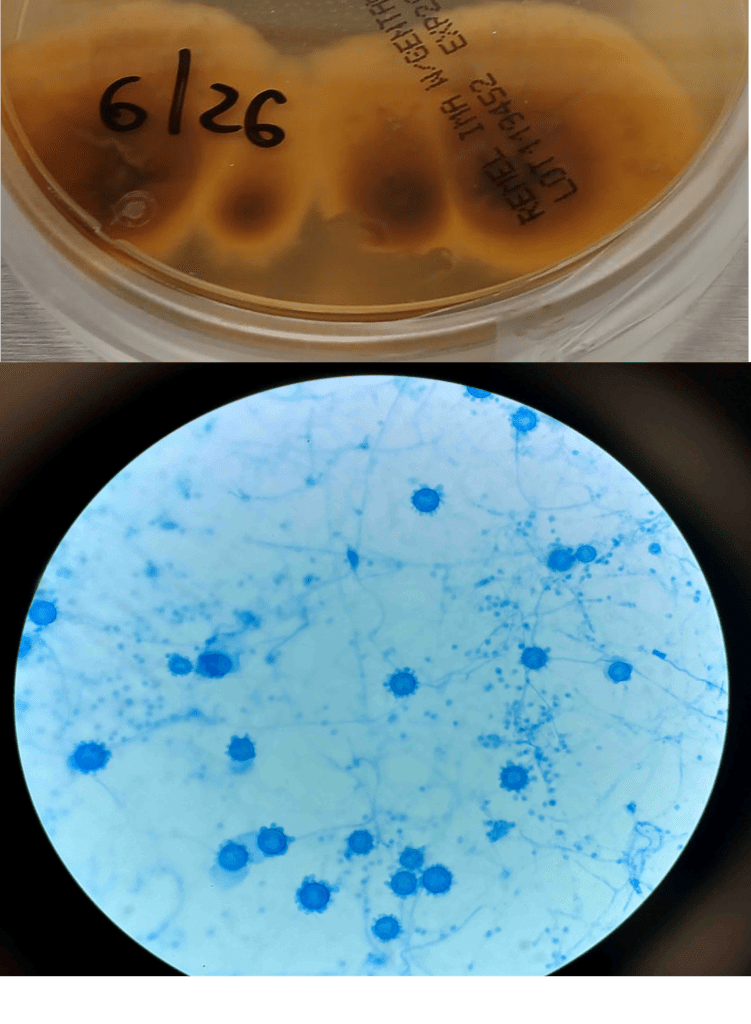

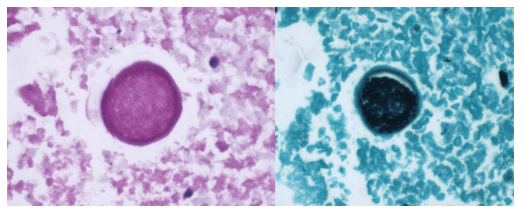

A 58-year-old woman with past medical history significant for degenerative joint disease and an approximately 30-pack per year smoking history was referred for low-dose computed tomography (CT) scan by her primary care provider to screen for lung cancer. An 8-mm nodule was observed in the lingula of the left lung. Follow up PET scans showed mild hypermetabolic activity in this nodule, as well as in axillary and subpectoral lymph nodes. The patient underwent a left video-assisted thoracic surgery to remove the nodule, and intraoperative frozen sectioning of the nodule showed necrosis but was negative for malignancy. On further discussion with the patient, it was discovered that she had spent several years living in Arizona and had participated in outdoor activities but had never observed any acute or chronic respiratory symptoms. On hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the nodule from biopsy, necrotizing granulomas and endospore-containing spherules were noted. These structures, consistent with Coccidioides, were also visualized under Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, Of note, tissue culture of the specimen was negative after eight weeks (image 1).

Discussion

Coccidioides species, particularly C. immitis and C. posadasii, are dimorphic fungi endemic to the Western hemisphere and have been documented in North, Central, and South America. Within the United States, Coccidioides has historically been associated with the arid southwestern states, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noting that many cases of coccidioidomycosis originate in California and Arizona.1 However, both the CDC and a 2022 study evaluating rates of coccidioidomycosis diagnosis have identified cases across the country, most frequently among travelers to high-prevalence areas. In the United States, other regions of endemicity include southwestern New Mexico, Utah, Washington, and western Texas.1,2 This fungus grows best in soil as mycelia, which, in dry environments, develop into spores.3,4 These spores can be released into the air with disruption of the soil, through natural or man-made forces causing infection via inhalation. Generation of dust clouds such as through natural occurrences of earthquakes and windstorms have led to outbreaks and lead to increased risk of exposure for individuals around the area.1,2

Coccidioidomycosis, also called “valley fever”, is a syndrome characterized by pulmonary and systemic symptoms, though it is more frequently asymptomatic. The incubation period is typically 1 to 3 weeks. Patients frequently present several weeks after exposure with fever, chills, night sweats, cough, and arthralgias.4 Given the general nature of these symptoms, it is believed that many cases are undiagnosed or misattributed to other causes of community acquired pneumonia. Mild pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is frequently self-resolving over the course of weeks to months, but persisting respiratory infection in patients previously thought to have bacterial or viral pneumonia can be the first indication of a fungal etiology.3 A small percentage of affected patients can develop more complex disease, including more severe pulmonary involvement and disseminated infection. Complex pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pleural effusion, nodules, and cavities. Empyema can occur as a consequence of fistula formation between a peripheral cavitary lesion and the pleural space.3 Disseminated disease has numerous manifestations, including cutaneous and soft tissue disease, osteomyelitis, synovitis, and meningitis.

Coccidioides can also be isolated from respiratory specimens, tissue biopsies and cerebrospinal fluid using routine fungal culture medium. Direct staining for the fungal elements (and sometimes spherules) from unfixed specimens can be done using calcofluor white, fluorescent stain. Procedures that involve manipulation of the sporulating dimorphic molds such as Coccidioides require biosafety level 2 practices and facilities and should be performed in a class II biological safety cabinet. Lifting of the culture plate lid is sufficient to release numerous spores into the environment capable of causing an infection.4 Cultured Coccidioides poses an occupational risk, as there have been reports of laboratory personnel developing symptoms of infection after working with the cultured fungus. As with other dimorphic molds, these organisms exhibit two forms: the mold form grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar or potato dextrose agar grown at 25C and a yeast form when grown at 37C. Mycelia are often visible within the first several days of incubation at 25C. The mold colonies may be white to grey, and sometimes tan or red with age. Microscopic examinations may reveal septate, hyaline, hyphae. Coccidioides form arthroconidia which are one-cell length, cylindrical to barrel-shaped with thick, smooth walls in their hyphae. The arthroconidia may alternate with empty disjunctor cells, giving the impression of alternating staining hyphae. True arthroconidia like Coccidioides will fragment. At 37C, Coccidioides develop into spherules, thick-walled structures where numerous endospores develop. The spherule form is rarely isolated in cultures but can be visualized on PAS, GMS, or H&E stains from fixed tissues.4

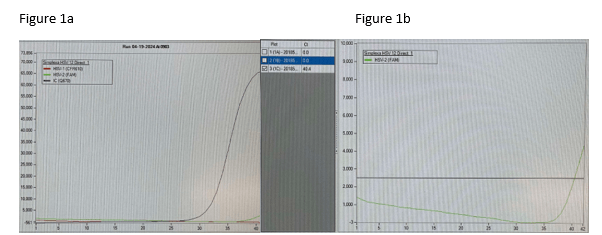

Diagnosis can also be made using serological testing, including enzyme immunoassay, immunodiffusion, and complement fixation IgM and IgG assays. These tests have varying sensitivities and specificities, often depending on the manufacturer of the test, though complement fixation and immunodiffusion methods in general have high sensitivities, rendering a positive result as virtually diagnostic.3 Coccidioidin is typically the antigen from the mycelial phase of the mold that is used for serological tests. A positive result from an immunodiffusion complement fixation test typically is indicative of a recent or chronic infection with IgG antibodies detected 2-6 weeks after onset of symptoms. On the other hand, the complement fixation test becomes positive 4-12 weeks after infection. Evaluating the titers can help determine the time and severity of infection. A titer <1:4 suggest early to residual disease whereas titers >1:16 could suggest disseminated disease beyond the respiratory tract.6 Any detection of antibodies from CSF is suggestive of meningitis caused by Coccidioides. Of note, in scenarios where there are discrepant results between serological tests, the patient should be investigated for histoplasmosis or blastomycosis. Antigen detection for Coccidioides species have been developed but performance is poor in urine but slightly higher in CSF specimens; similarly, Beta-D-glucan testing in serum for coccidioidomycosis also has limited value.7,8.9 Molecular methods of diagnosis have also been developed, but only one PCR test has been FDA approved with comparable sensitivity to cultures.10

Treatment of primary pulmonary and disseminated coccidioidomycosis typically consist of the triazoles such as voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole. Amphotericin B can also be used, though this is usually reserved for poor responding or rapidly progressing infection, given its side effects.11 Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk for disseminated infection whereas immunocompetent individuals may recover without treatment. The Infectious Diseases Society of America notes that mild cases of limited pulmonary involvement can be managed with observation and supportive measures alone.12

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Cases of Valley Fever. Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis). September 23, 2024. Accessed January 17, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/valley-fever/php/statistics/index.html

2. Mazi PB, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. The Geographic Distribution of Dimorphic Mycoses in the United States for the Modern Era. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(7):1295-1301. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac882

3. Johnson RH, Sharma R, Kuran R, Fong I, Heidari A. Coccidioidomycosis: a review [published correction appears in J Investig Med. 2021 Dec;69(8):1486. doi: 10.1136/jim-2020-001655corr1]. J Investig Med. 2021;69(2):316-323. doi:10.1136/jim-2020-001655

4. McHardy IH, Barker B, Thompson GR 3rd. Review of Clinical and Laboratory Diagnostics for Coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61(5):e0158122. doi:10.1128/jcm.01581-22

5. David A. Stevens, Karl V. Clemons, Hillel B. Levine, Demosthenes Pappagianis, Ellen Jo Baron, John R. Hamilton, Stanley C. Deresinski, Nancy Johnson, Expert Opinion: What To Do When There Is Coccidioides Exposure in a Laboratory, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 49, Issue 6, 15 September 2009, Pages 919–923, https://doi.org/10.1086/605441

6. Smith CE, Saito MT, Simons SA. 1956. Pattern of 39,500 serologic tests in coccidioidomycosis. JAMA 160:546–552. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02960420026008.

7. Durkin M, Connolly P, Kuberski T, Myers R, Kubak BM, Bruckner D, Pegues D, Wheat LJ. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with use of the Coccidioides antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Oct 15;47(8):e69-73. doi: 10.1086/592073. PMID: 18781884.

8. Kassis C, Zaidi S, Kuberski T, Moran A, Gonzalez O, Hussain S, Hartmann-Manrique C, Al-Jashaami L, Chebbo A, Myers RA, Wheat LJ. Role of Coccidioides Antigen Testing in the Cerebrospinal Fluid for the Diagnosis of Coccidioidal Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Nov 15;61(10):1521-6. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ585. Epub 2015 Jul 24. PMID: 26209683.

9. Thompson GR 3rd, Bays DJ, Johnson SM, Cohen SH, Pappagianis D, Finkelman MA. Serum (1->3)-β-D-glucan measurement in coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Sep;50(9):3060-2. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00631-12. Epub 2012 Jun 12. PMID: 22692738; PMCID: PMC3421794.

10. Vucicevic D, Blair JE, Binnicker MJ, McCullough AE, Kusne S, Vikram HR, Parish JM, Wengenack NL. The utility of Coccidioides polymerase chain reaction testing in the clinical setting. Mycopathologia. 2010 Nov;170(5):345-51. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9327-0. Epub 2010 Jun 10. PMID: 20535639.

11. Ampel NM. The Treatment Of Coccidioidomycosis.Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015 Sep;57 Suppl 19(Suppl 19):51-6. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652015000700010. PMID: 26465370; PMCID: PMC4711193.

12. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):e112-46. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw360

–Anna Reed is currently a third year medical student at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She intends to pursue a pathology residency, followed by a fellowship in forensic pathology. Her academic interests include the role of pathology in disaster scenarios, various topics in microbiology, and ways to improve autopsy practices.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.