Against the backdrop of COVID-19, the world experienced a multicounty outbreak of Mpox (formally monkeypox) beginning in May of 2022. Prior to that time, the virus was primarily known to circulate within central and west African nations causing zoonotic disease. Clinical presentations of Mpox comprise signs and symptoms including rash on the hands, feet, face or mucous membranes and patients may experience fever or an influenza-like illness.1 Historically, transmission was associated with travel to an endemic region and contact with an infected animal. Importantly, the outbreak in 2022 was associated with broad changes in Mpox epidemiology, as most infections were acquired via sexual transmission.

Pox viruses and Mpox

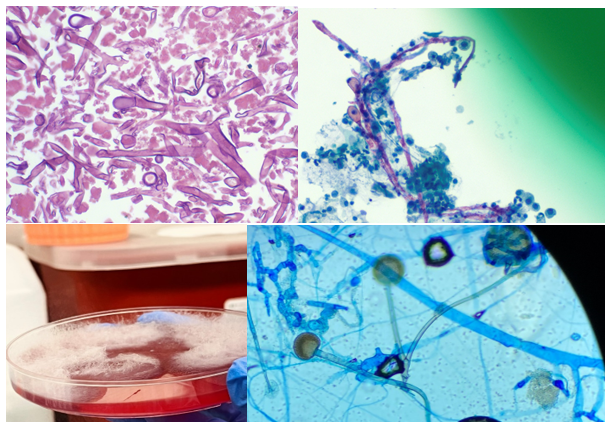

Pox viruses are members of the family Poxviridae, which are double stranded DNA viruses that replicate entirely in the cytoplasm of host cells. They have worldwide distribution and cause disease in humans and other animals. Infection typically manifests as the formation of lesions, skin nodules or rash. Mpox belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus which also includes other clinically important viruses including variola virus (smallpox), vaccinia virus, and cowpox. In the context of diagnosis, differentiation between the members of the Orthopox family becomes important.

The duration of illness with Mpox is usually between 2-4 weeks, with a variable incubation time most often between 6-13 days. The Mpox rash has historically been more focused on the face and extremities,2 and will cycle through stages including encrustation, scabbing, and eventually resolution. During the 2022 outbreak, an increasing number of presentations involved the anogenital and oral regions, further highlighting the change in epidemiology. The window for transmission is currently an area of active research as new data suggests transmission can begin prior to the appearance of symptomology.3

Diagnosis – Molecular

Mpox is generally diagnosed using PCR testing from a swabbed lesion. At the onset of this emerging infectious disease, the CDC shared its algorithm and testing for Mpox with public health laboratories. The first-generation algorithm largely reflected its potential use as a tool for screening for bioterrorism agents, which included using two-tiered testing. The first test was designed to demonstrate that Orthopox DNA was present and rule out variola virus by targeting the Orthopox DNA polymerase gene found not present in Variola (E9L-NVAR). The second step was to target an Mpox-specific gene encoding the envelope protein (B6R).4 It soon was readily apparent that the only Orthopox virus in circulation was Mpox, so the CDC updated its guidance in late June 2022 to confirming diagnosis of Mpox with the single Orthopox DNA-polymerase PCR assay.

However, despite this modification to improve expediency and like the situation faced at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for testing greatly exceeded what public health infrastructure could support. Thus, laboratories designed and validated laboratory developed tests (LDTs) to expand access to testing, thus enabling physicians to interrogate the causes of a patient’s rash more thoroughly. This flexibility was essential given rising cases numbers and relatively non-specific symptomology of Mpox. By May 2023, over 80 laboratories registered Mpox LDTs with the Food and Drug Administration,5 and commercial device manufacturers are now including it in new and forthcoming assays still in development.

Diagnosis – Histopathology

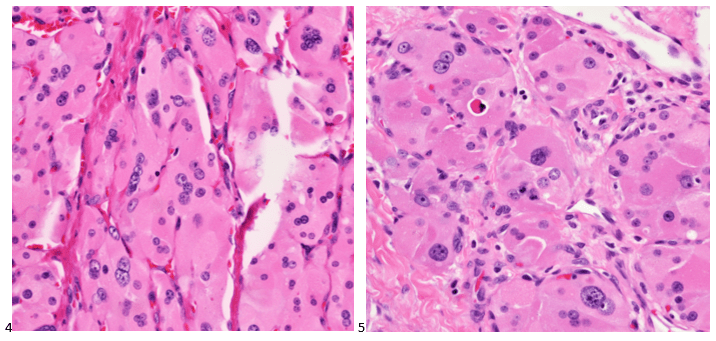

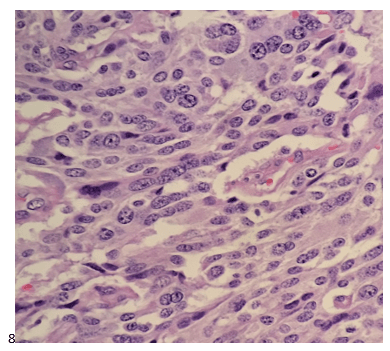

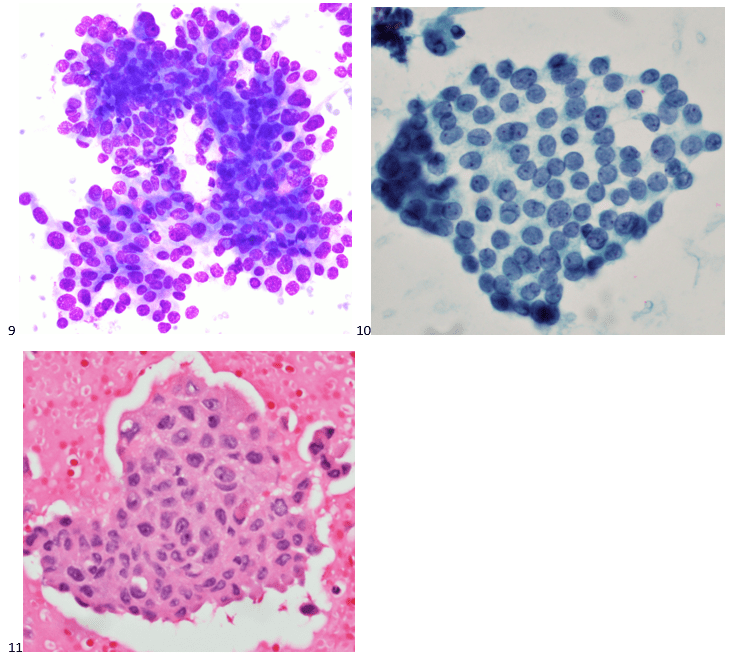

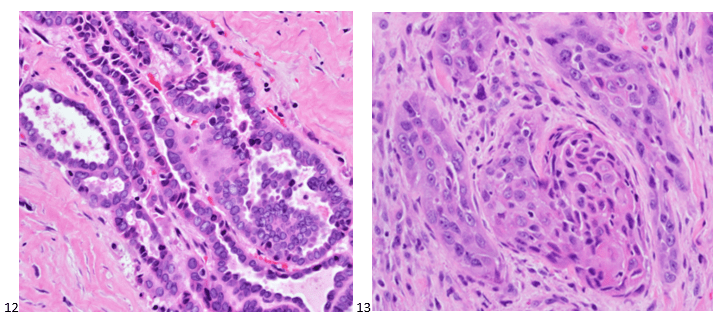

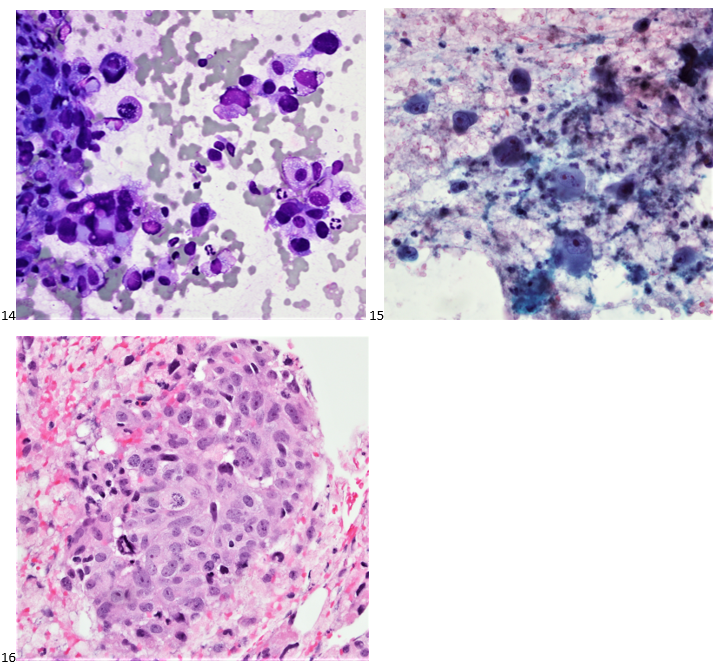

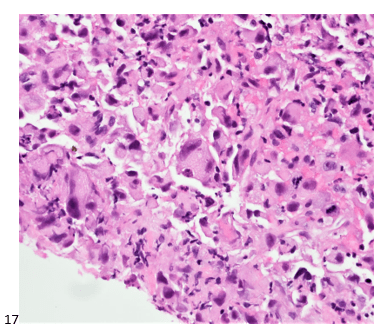

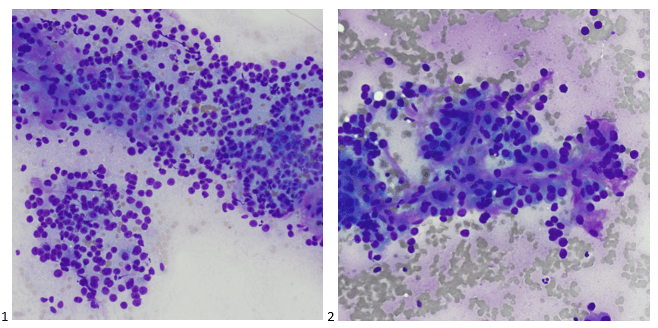

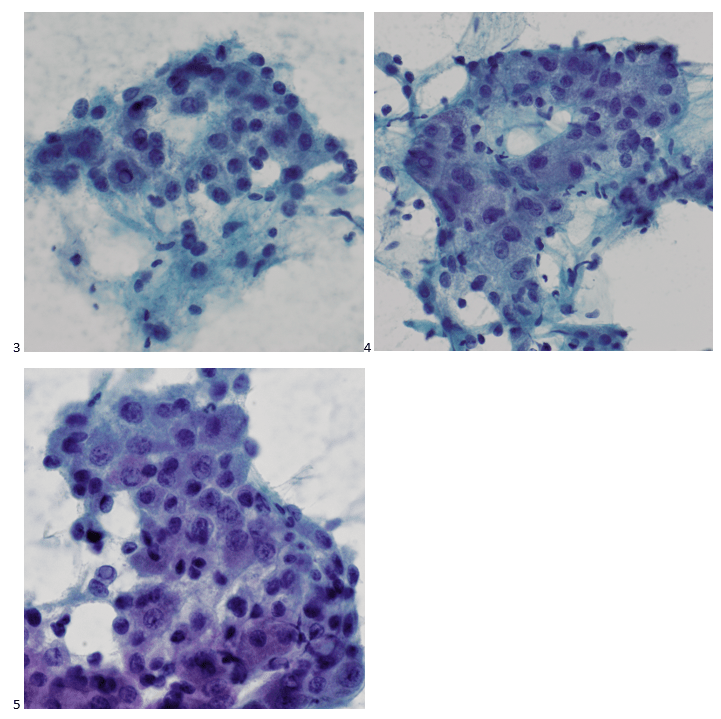

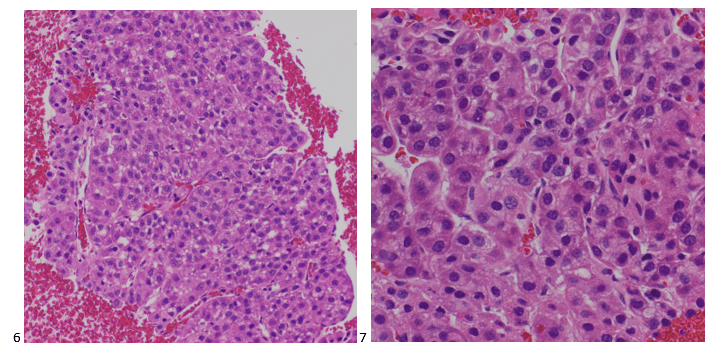

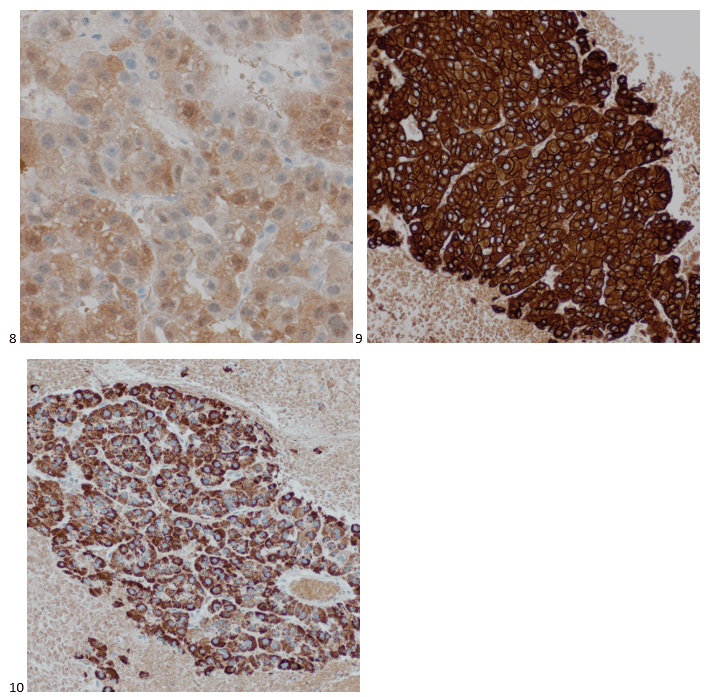

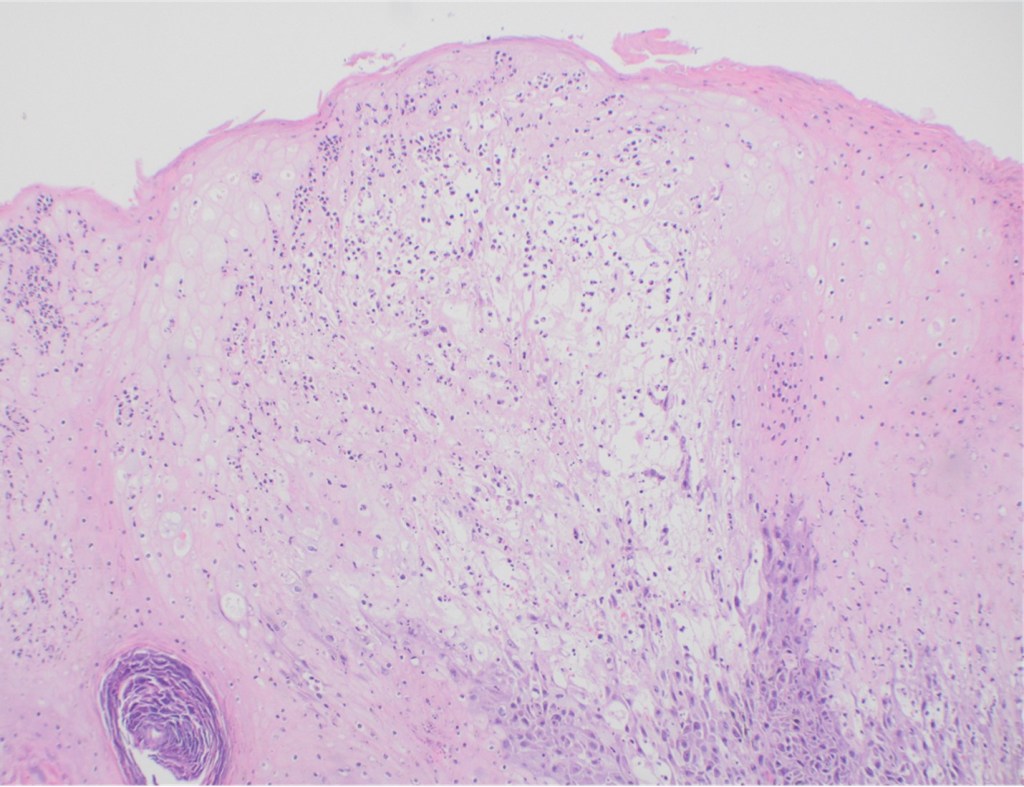

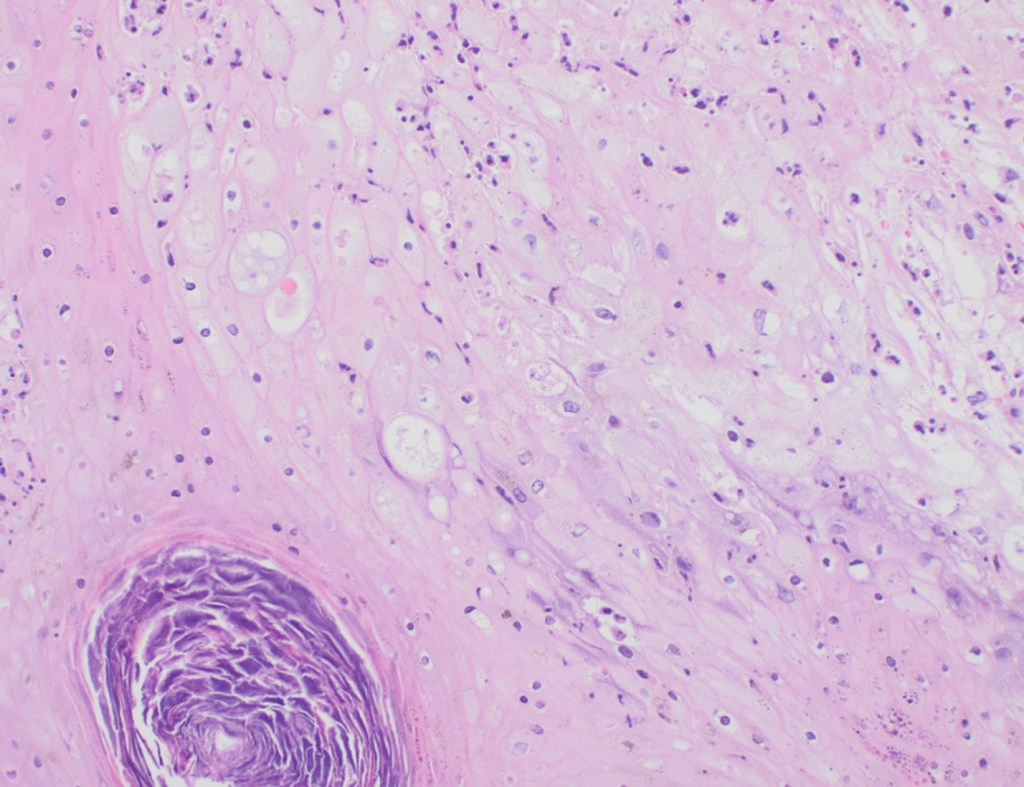

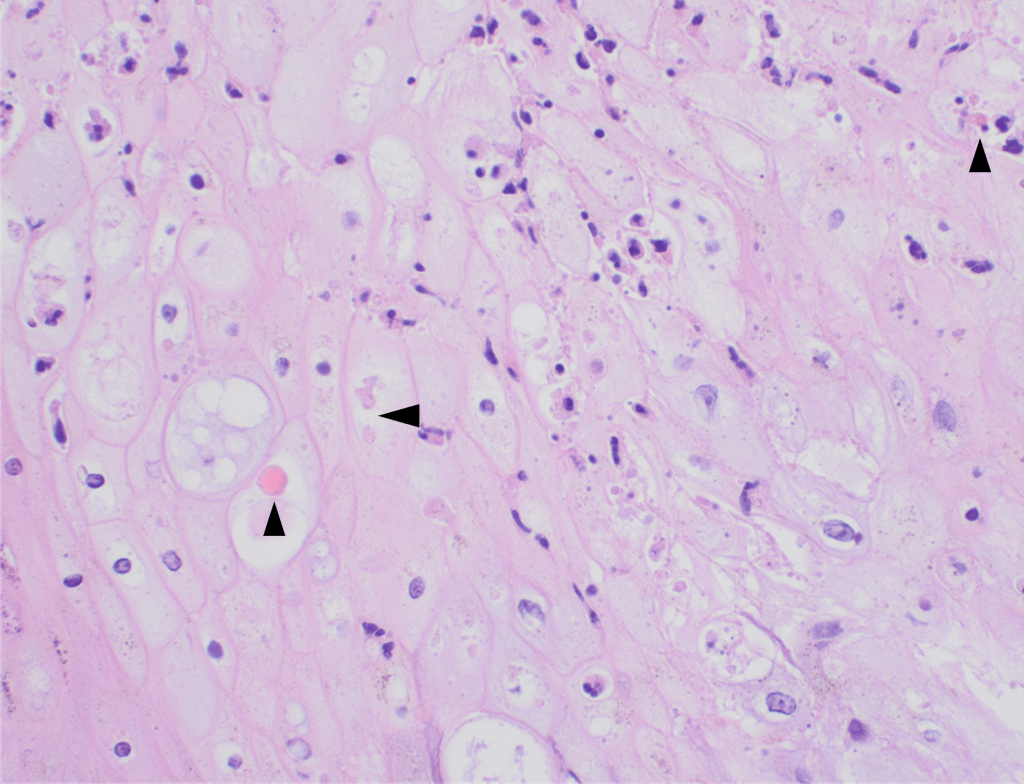

Although PCR testing is the mainstay of diagnosis, histopathologic evaluation of biopsy material from a lesion can also provide insight into the viral etiology. Mpox infected skin biopsies demonstrate similar histopathologic features of infections caused by other pox viruses. As the rash continues to evolve over time, representative histopathological changes can also be observed. Early lesions may demonstrate ballooning degeneration, acanthosis and spongiosis. More mature lesions progress to near total keratinocyte necrosis with exocytosis comprised of mixed cellular inflammatory infiltrate.6 Eosinophilic bodies may be identifiable in the cytoplasm of infected cells, commonly known as Guarnieri bodies, represent the mature virions produced in the cytoplasm of infected cells.

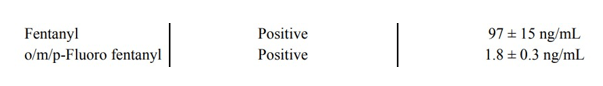

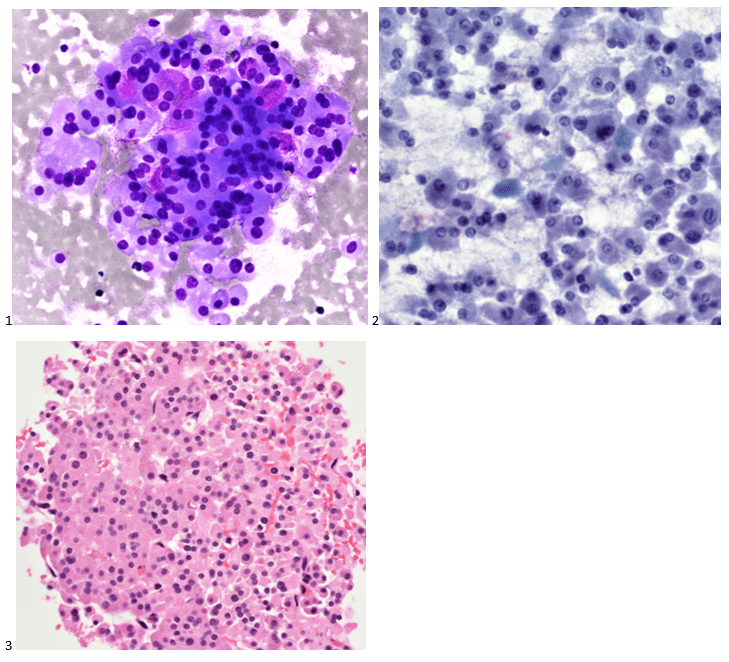

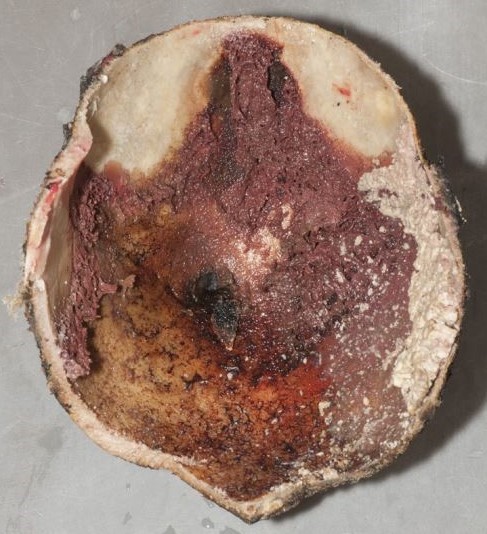

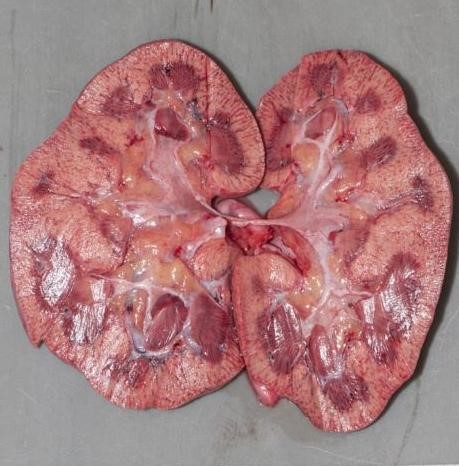

Recently, the histopathological description of 20 outbreak-associated clinical cases of Mpox from Spain was reported. Epidermal necrosis and keratinocytic ballooning were commonly encountered microscopic features associated with Mpox lesions.7 Figure 1 is a skin biopsy from a patient who presented with a vesicular eruption in September with a history of mpox, syphilis and herpes simplex infection whose lesions were worsening. It similarly shows ballooning degeneration, epidermal necrosis, exocytosis of neutrophils into the epidermis, and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions (Guarnieri bodies) (Figures 2-3).

High power magnification of viral inclusions, guarnieri bodies, (arrowheads) in a background of necrotic keratinocytes and neutrophilic infiltrate.

Treatment

Mpox is much milder than smallpox despite similar rash manifestations. In cases of severe Mpox infection, therapies used for smallpox have been compassionately utilized, but supportive measures are the mainstay of management of uncomplicated cases. Vaccination is now available as both a pre-exposure prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis. It is important to note that the clinical effectiveness of the currently used vaccine in the United States is not known; however, early data across 32 US jurisdictions showed that among males 18-49, those who were unvaccinated had an Mpox incidence 14 times higher than similarly aged males who received at least one dose of vaccine at least 2 weeks prior.8

Conclusion

The Mpox outbreak, declared a global health emergency in July of 2022, has reinforced the need for flexibility within laboratories and industry to respond to emerging infectious diseases. The global health emergency for Mpox was declared over on May 11, 2023, but cases are still going to sporadically occur and minor outbreaks will result. The rapid development of numerous LDTs was essential to support the overwhelmed public health infrastructure, and this continued flexibility is needed to appropriately respond to future public health emergencies.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/symptoms/index.html. Accessed April 19th, 2023.

- Saxena et al. J. Med. Virol. 2022;95:e27902. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.27902

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/about/science-behind-transmission.html Accessed May 19th, 2023

- Li Y, Olson VA, Laue T, Laker MT, Damon IK. Detection of monkeypox virus with real-time PCR assays. J Clin Virol. 2006 Jul;36(3):194-203. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.03.012. Epub 2006 May 30. PMID: 16731033; PMCID: PMC9628957.

- https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/monkeypox-mpox-and-medical-devices#Laboratories. Accessed May 3, 2023.

- Bayer-Garner IB. Monkeypox virus: histologic, immunohistochemical and electron-microscopic findings. J Cutan Pathol. 2005 Jan;32(1):28-34. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00254.x. PMID: 15660652.

- Rodríguez-Cuadrado FJ, Nájera L, Suárez D, Silvestre G, García-Fresnadillo D, Roustan G, Sánchez-Vázquez L, Jo M, Santonja C, Garrido-Ruiz MC, Vicente-Montaña AM, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Requena L. Clinical, histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic findings in cutaneous monkeypox: A multicenter retrospective case series in Spain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 Apr;88(4):856-863. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.027. Epub 2022 Dec 26. PMID: 36581043; PMCID: PMC9794029.

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/vaccines/vaccine-considerations.html. Accessed May 3, 2023.

-Clare McCormick-Baw, MD, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Microbiology at UT Southwestern in Dallas, Texas. She has a passion for teaching about laboratory medicine in general and the best uses of the microbiology lab in particular.

-Travis Vandergriff, MD is an Associate Professor and Board-Certified Dermatopathologist and practicing Dermatologist at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

-Andrew Clark, PhD, D(ABMM) is an Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in the Department of Pathology, and Associate Director of the Clements University Hospital microbiology laboratory. He completed a CPEP-accredited postdoctoral fellowship in Medical and Public Health Microbiology at National Institutes of Health, and is interested in antimicrobial susceptibility and anaerobe pathophysiology.