Case History

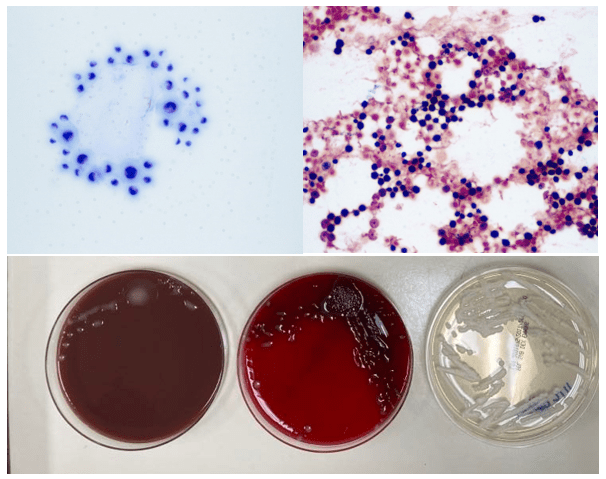

A 34 year old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute onset abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, persistent fever, and chills. His physical examination at that time was consistent with appendicitis. Patient was treated with Zosyn for broad coverage. Imaging showed a normal appendix. Three days later after blood was drawn, his blood cultures flagged positive for gram negative, elongated, thin rods. Growth was determined to be Fusobacterium mortiferum by MALDI-TOF. Ampicillin/sulbactam was started and patient was given Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for outpatient treatment. Further follow-up of the patient showed normal white blood count and normal urinalysis. Repeat blood cultures were negative.

Discussion

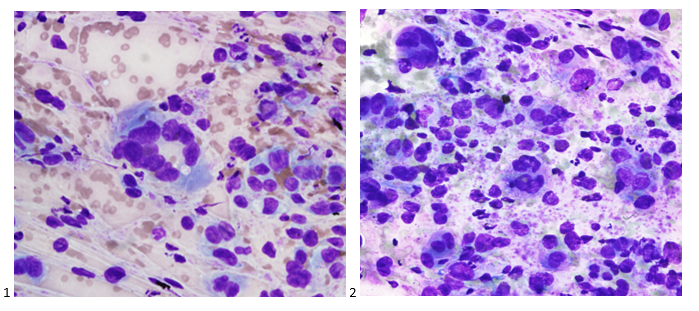

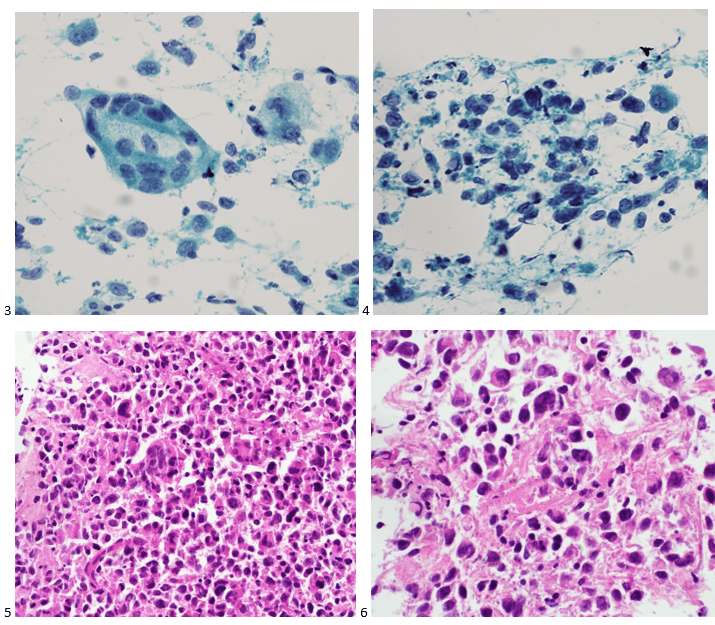

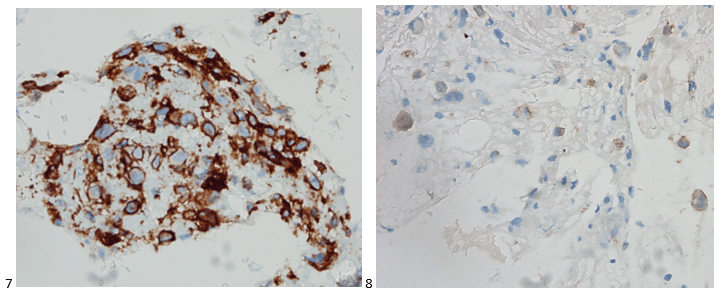

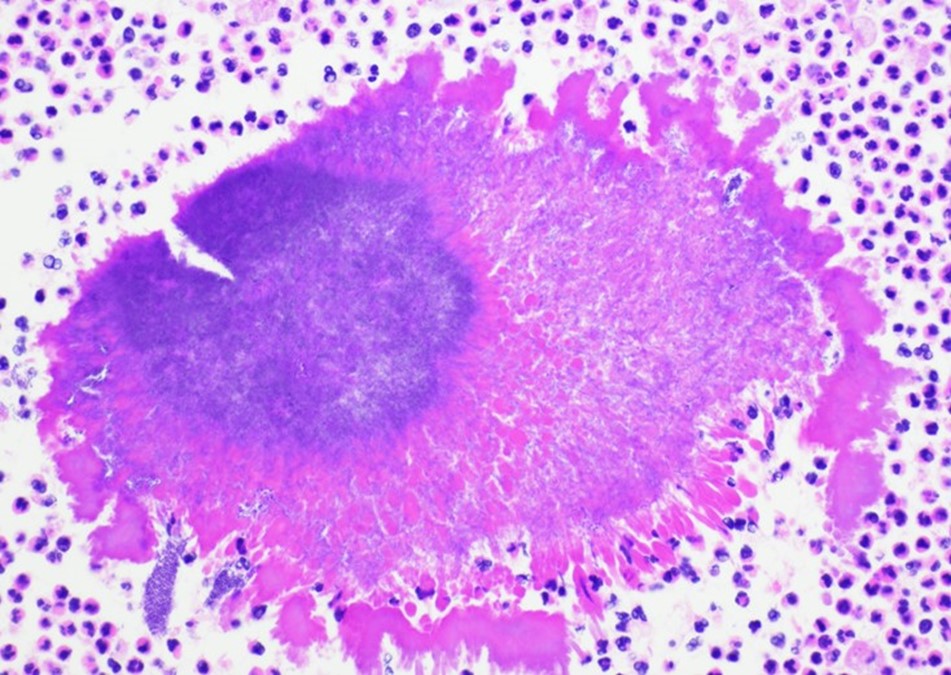

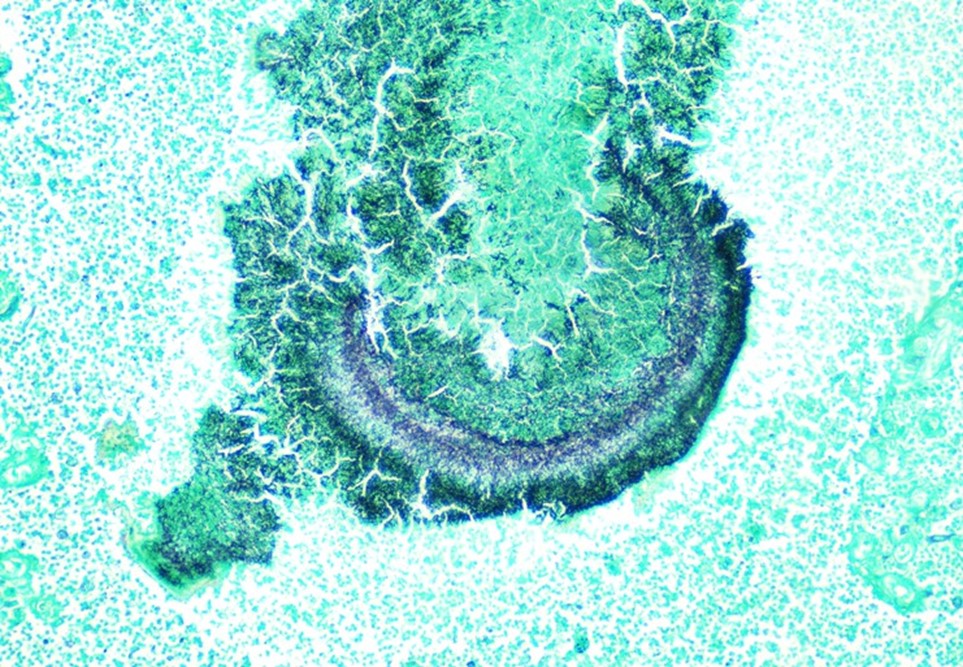

Fusobacteria are anaerobic, gram negative, spindle-shaped rods with pointed ends. They are part of the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal flora in humans but can cause diseases ranging from tonsillitis to septic shock.1 Fusobacterium nucleatum and necrophorum are commonly isolated in human diseases, although other species such as Fusobacterium mortiferum, as described in our case, have occasionally been documented as a secondary cause of septicemia 2 or bacteremia 1 and in rare instances implicated in the development of thyroid abscess.3

F. nucleatum is a member of oropharyngeal flora and unsurprisingly involved in gingival and periodontal diseases.4 It has been also described as the most likely cause of extra-oral infections among oral anaerobes.5 F. nucleatum has been detected in various fetal and placental tissues associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis and preterm rupture of membranes.6 Recent studies have reported this species to be abundant in colon, esophageal carcinoma, pancreatic and breast cancers. It is associated with poor prognosis in colon, rectal, pancreatic and esophageal cancers by promoting pro-tumorigenic immune microenvironment and reduction in the number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.7, 10 One of the proposed theories is the involvement of the Fap2 virulence factor that has been described to inhibit tumor cell clearance in colorectal cancer cells.8 The other commonly isolated species is F. necrophorum, which is associated with oropharyngeal infection followed by septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein with sepsis and metastatic diseases typically involving the lungs. This syndrome is known as Lemiere’s disease first described in 1936 by Andre Lemierre. F. necrophorum usually causes infection in young, otherwise healthy adults in contrast to F. nucleatum1 which is associated more with the elderly population. According to Afra et al most of the mortality cases were due to F. nucleatum as opposed to F. necrophrum. This could be attributed to co-morbidities in elderly patients with positive F. nucleatum cultures.

Fusobacterium species can be identified using mass spectrometry MALDI-TOF. Typically, Fusobacterium species are resistant to vancomycin, but susceptible to colistin and kanamycin disk identification tests; however, F. nucleatum is susceptible to all three drugs. F. mortiferum and F. varium grow in the presence of bile. F. necrophorum shows positive indole and negative nitrate testing. Sequencing of the 16S RNA gene and 16S-23S rRNA gene spacer region can be used to determine the different species3,9

Fusobacterium species are usually susceptible to penicillin, clindamycin, metronidazole, and chloramphenicol and resistant to macrolides. F. nucleatum and F. necrophorum may produce beta-lactamases.3 In rare cases, surgical intervention is warranted for abscess formation.

References

- Afra K, Laupland K, Leal J, Lloyd T, Gregson D. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of fusobacterium species bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-264.

- Prout J, Glymph R. Fusobacterium mortiferum septicemia. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 1985;7(4):29. doi: 10.1016/s0196-4399(85)80052-0.

- Stavreas NP, Amanatidou CD, Hatzimanolis EG, et al. Thyroid abscess due to a mixed anaerobic infection with fusobacterium mortiferum. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(12):6202. doi: 10.1128/jcm.43.12.6202-6204.2005.

- Moore WE, Moore LV. The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994 Jun;5:66-77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00019.x. PMID: 9673163.

- Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996 Jan;9(1):55-71. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.1.55. PMID: 8665477; PMCID: PMC172882.

- Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum: A commensal-turned pathogen. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2015;23:141. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013.

- Alon‐maimon T, Mandelboim OO, Bachrach G. Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontology 2000. 2000;89(1):166. doi: 10.1111/prd.12426.

- Umaña A, Sanders BE, Yoo CC, Casasanta MA, Udayasuryan B, Verbridge SS, Slade DJ. Utilizing Whole Fusobacterium Genomes To Identify, Correct, and Characterize Potential Virulence Protein Families. J Bacteriol. 2019 Nov 5;201(23):e00273-19. doi: 10.1128/JB.00273-19. PMID: 31501282; PMCID: PMC6832068.

- Garcia-Carretero R, Lopez-Lomba M, Carrasco-Fernandez B, Duran-Valle MT. Clinical features and outcomes of fusobacterium species infections in a ten-year follow-up. The Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2017;3(4):141. doi: 10.1515/jccm-2017-0029.

- Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Fusobacterium nucleatum — symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;17(3):156. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0129-6.

-Dr. Hayk Simonyan was born and raised in Yerevan, Armenia. He attended Yerevan State Medical University after Mkhitar Heratsi where he received his doctorate degree. He did his research at The George Washington University. His studies were focused on transcription factor activation in the SFO-PVN axis that leads to cardio-metabolic changes mediated by obesity, oxidative stress, and angiotensin-II. One of his other projects included collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, working on alternative treatment for glioblastoma multiforme. His academic interests include surgical pathology and molecular. In his spare time, Hayk enjoys spending time with family, playing soccer, tennis, and skiing. Hayk is pursuing AP/CP training.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.