Case History

A 66 year old man with past medical history of recently diagnosed Clostridioides difficile colitis presented to emergency department with diarrhea, weight loss of 52 pounds in 4 months, and occasional night sweats. CT imaging revealed dilation of small bowel with thickened mucosal folds. The duodenum was subsequently biopsied to reveal diffuse intestinal lymphangiectasia containing PAS positive and Congo red negative eosinophilic material and lamina propria foamy macrophages. Laboratory investigations revealed normocytic anemia, proteinuria, and peripheral IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy.

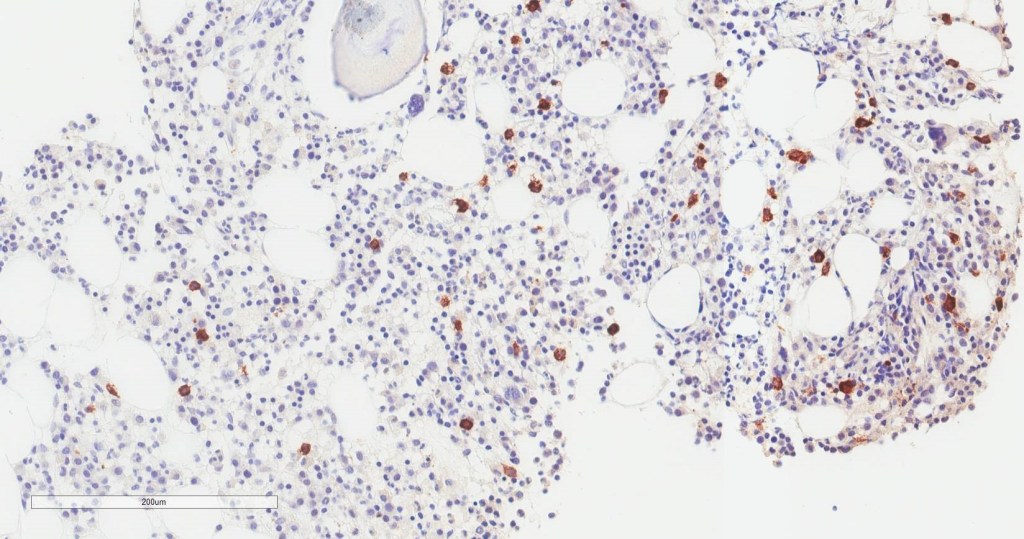

Biopsy Findings

Bone marrow aspirate shows increased plasma cells and mast cells. H&E stained sections demonstrate a normocellular bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis and involvement by 35% plasma cells. By immunohistochemistry, CD138 highlights clusters of plasma cells that predominantly express kappa light chain restriction.

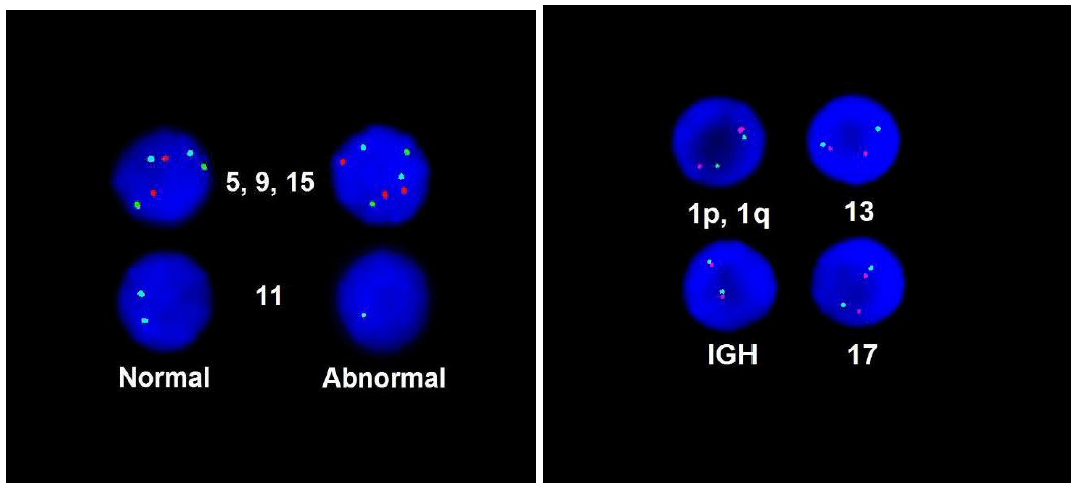

FISH and Mutation Analysis

FISH demonstrated loss of chromosome 11 and gain of chromosome 15, which was consistent with plasma cell dyscrasia. MYD88 mutation analysis did not detect the mutation.

Diagnosis

The findings of the patient’s normocytic anemia, IgM monoclonal gammopathy, and intestinal lymphangectasia with an associated plasma cell dyscrasia involving the bone marrow favor a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

Discussion

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) is a malignant B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the bone marrow and peripheral IgM monoclonal gammopathy.1 It is rare with an overall incidence of 3 per million persons per year, accounting for 1-2% of hematologic cancers.1 It occurs predominantly in Caucasian males, with a median age of 63-68 years old at diagnosis.1-3

Patient may be asymptomatic for years and require observation or experience a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms. These symptoms may be attributable to the tumor infiltration of the bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, IgM circulating in the blood, and IgM depositing into tissues. The most common clinical presentation of WM is fatigue and nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss, due to normochromic, normocytic anemia. 20-30% of patients may exhibit lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly due to infiltration of peripheral tissues. High concentration of IgM in the circulation may lead to hyperviscosity, resulting in oronasal bleeding, gingival bleeding, blurred vision due to retinal hemorrhages, and neurological symptoms, including headache, ataxia, light-headedness, dizziness, and rarely, stroke.2-3 The gastrointestinal manifestations are rare; however, IgM monoclonal protein may deposit into the lamina propria of the GI tract, causing diarrhea, steatorrhea, and GI bleeding.4 Other IgM-related manifestations include cold agglutinin hemolytic anemia, cryoglobulin, and amyloid deposition in tissues.3

Diagnosis of WM includes evidence of IgM monoclonal gammopathy and at least 10% of bone marrow infiltration by lymphoplasmacytic cells.5 Monoclonal gammopathy can be detected by the monoclonal spike, or M-spike, on serum protein electrophoresis.3 Serum immunofixation may be performed to identify the type of monoclonal protein and the type of light chain involved.3 In terms of immunophenotype, neoplastic cells express surface IgM, cytoplasmic Igs, CD38, CD79a, and pan B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, and CD22). CD10 and CD23 are absent. Expression of CD5 occurs in approximately 5-20% of cases.6 Recent studies have reported two most common somatic mutations in WM, which are MYD88 L265P mutations (90-95% of cases) and CXCR4 (30–40% of cases).7 Absence of these mutations, however, do not completely exclude the diagnosis of WM.

The International Staging System for WM identifies five factors associated with adverse prognosis, including age older than 65, hemoglobin < 11.5g/dL, platelet count < 100K/μL, beta-2-microglobulin > 3mg/L, and monoclonal IgM concentration > 7g/L.3 Patients younger than the age of 65 years with 0 or 1 of these factors are in the low-risk category with a median survival of 12 years.3 In contrast, patients with 2 or more risk factors are in the intermediate- and high-risk categories and have a median survival of almost 4 years. 3

Management of WM depends on the patient’s clinical manifestations.Furthermore, patients with minimal symptoms should be managed with rituximab, whereas patients with severe symptoms related to WM should receive more aggressive treatment, including dexamethasone, rituximab and cyclophosphamide. Hyperviscosity syndrome is an oncologic emergency that requires removal of excess IgM from the circulation via plasmapheresis.8

References

- Neparidze N, Dhodapkar MV. Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia: Recent advances in biology and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Onco. 2009 Oct;7(10): 677-690.

- Leleu X, Roccaro AM, Moreau AS, Dupire S, Robu D, et al. Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia. Cancer Lett. 2008 Oct;270(1):095-107.

- Tran T. Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a review of laboratory findings and clinical aspects. Laboratory Medicine. 2013 May;44(2):e19-e21.

- Kantamaneni V, Gurram K, Khehra R, Koneru G, Kulkarni A. Distal illeal ulcers as gastrointestinal manifestation of Waldenstrom Macroglbulinemia. 2019 Apr; 6(4):pe00058.

- Grunenberg A, Buske C. Monoclonal IgM gammopathy and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Nov;114(44):745-751.

- Bhawna S, Butola KS, Kumar Y. A diagnostic dilemma: Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia/plasma cell leukemia. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:271407.

- Varettoni M, Zibellini S, Defrancesco I, Ferretti VV, Rizzo E, et all. Pattern of somatic mutations in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia or IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

- Oza A, Rajkumar SV. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: prognosis and management. Blood Cancer Journal. 2015;5:e394.

-Jasmine Saleh, MD MPH is a pathology resident at Loyola University Medical Center with an interest in dermatopathology and hematopathology. Follow Dr. Saleh on Twitter @JasmineSaleh.

–Kamran M. Mirza, MD, PhD, MLS(ASCP)CM is an Assistant Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Medical Education and Applied Health Sciences at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine and Parkinson School for Health Sciences and Public Health. A past top 5 honoree in ASCP’s Forty Under 40, Dr. Mirza was named to The Pathologist’s Power List of 2018 and placed #5 in the #PathPower List 2019. Follow him on twitter @kmirza.