Case History

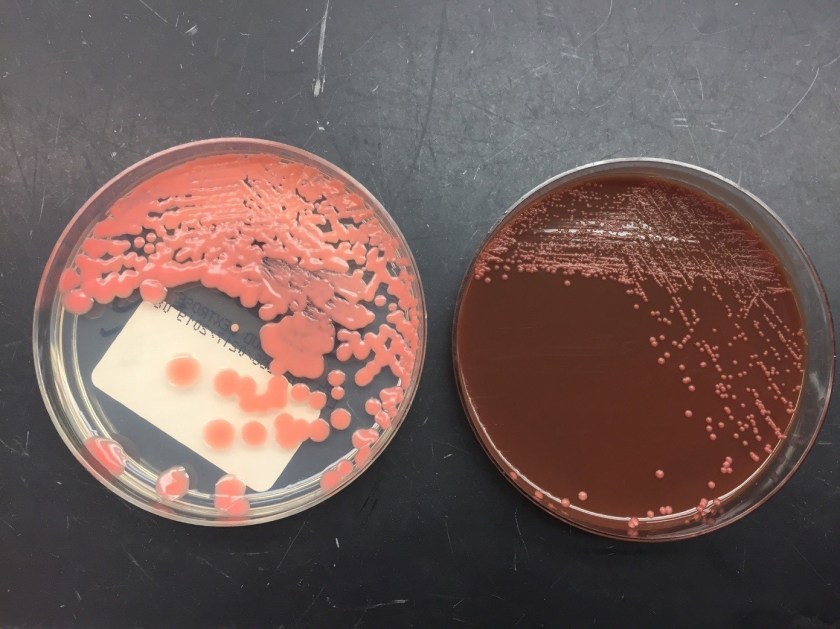

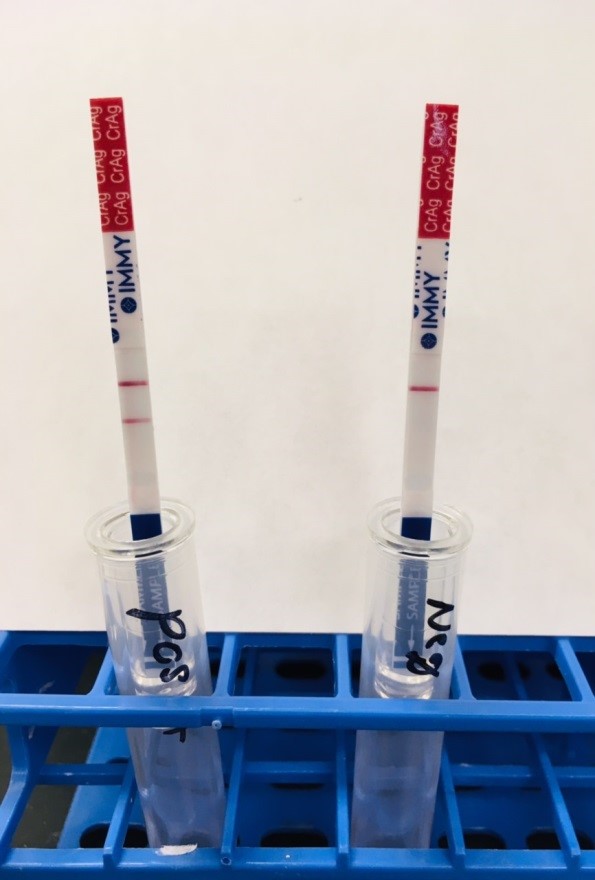

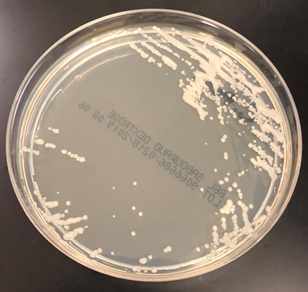

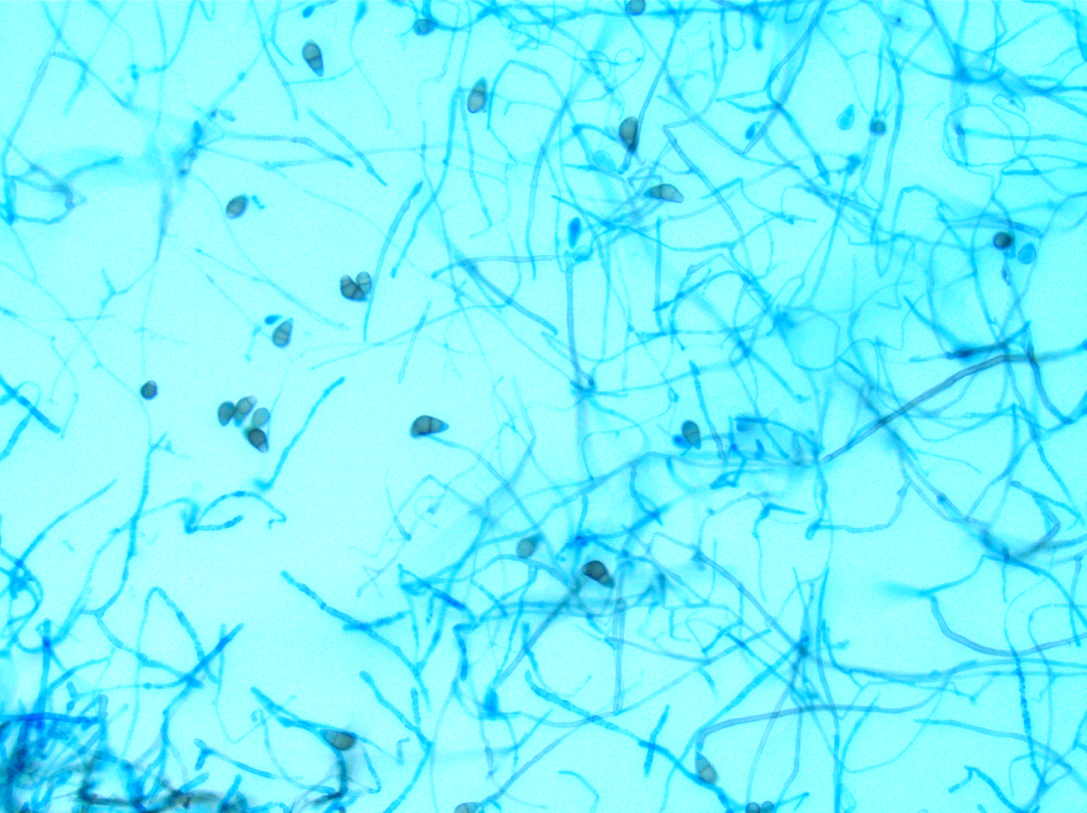

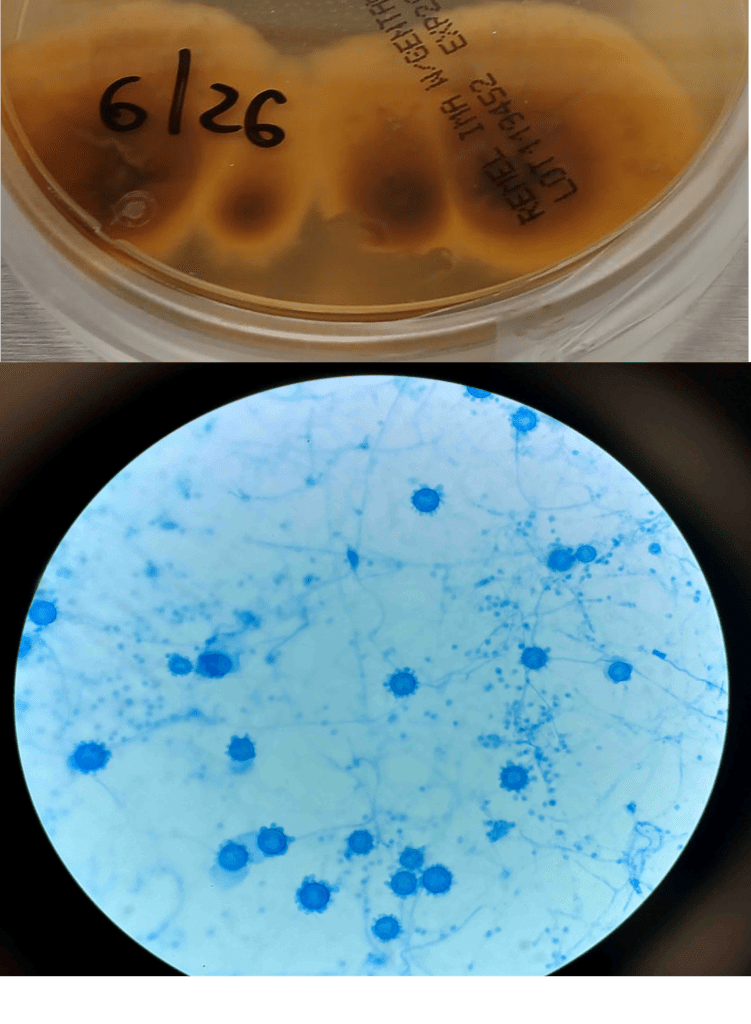

A 41-year-old male was admitted with myasthenia gravis exacerbation and respiratory difficulty. He was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis in 2004, underwent a thymectomy in 2010, and was taking prednisone (20 mg daily). He presented to another hospital one month ago with fever, chest pain, and shortness of breath. He was treated with antibiotics and antifungals for pneumonia, along with 5 days of immunoglobulin for a possible myasthenia gravis crisis, but showed no improvement. After admission, a CT scan revealed diffuse bilateral mixed airspace and ground-glass opacities without pleural effusions, most concerning for multifocal pneumonia. A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) staining showed hyphal and yeast elements. Both BAL and urine Histoplasma antigen tests were positive. He was started on posaconazole (300 mg daily), which led to an improvement in symptoms, and he was subsequently discharged. After 6 weeks of culture, macroscopic and microscopic features of the colony confirms Histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 1).

Discussion

Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus responsible for histoplasmosis, a respiratory infection. As with other dimorphic molds, this fungus exists as a mold in the environment at 25°C and converts to a yeast form once it infects a host at 37°C. It is primarily endemic in areas with rich soil, particularly in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, but has also been reported in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina. Outside the United States, histoplasmosis incidence is best understood and highest in parts of Mexico and South and Central America and is largely driven by the AIDS pandemic1,2. The fungus thrives in bird and bat guano due to the high nitrogen and organic content; common exposures include bird roosts, chicken houses, caves, and old buildings that are commonly visited by bats. Humans typically become infected through the inhalation of aerosolized spores. Demolition or building construction around these soiled environments can lead to outbreaks.

While most infections are asymptomatic, histoplasmosis can lead to severe illness in immunocompromised individuals. Histoplasma spores are deposited in the lungs, where they convert to the yeast form. These yeast cells are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, where they survive and multiply inside the cells. The fungus can then disseminate via the lymphatic and bloodstream systems to other organs 3. The clinical presentation of histoplasmosis varies depending on the host’s immune status and the level of fungal exposure. In most cases, the infection is asymptomatic or manifests as mild flu-like symptoms, including fever, fatigue, and cough. However, in cases of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, patients may experience pneumonia-like symptoms such as chest pain, cough, and fever. Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis can mimic tuberculosis, presenting with symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and a chronic cough. Pleural thickening and apical cavitary lesions are common. Extrapulmonary manifestations include granulomatous mediastinitis, fibrosing (sclerosing) mediastinitis, and broncholithiasis1. In severe disseminated cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, the infection can spread to multiple organs. Adrenal involvement may manifest as adrenal masses, adrenal insufficiency, or electrolyte imbalances. Gastrointestinal involvement is relatively common but rarely produces clinical symptoms4. Skin involvement occurs in up to 15% of cases in studies, more frequently in patients with AIDS. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement occurs in 5-20% of cases5.

Diagnosing histoplasmosis involves clinical suspicion, radiological studies, and laboratory tests. The most common radiographic findings are diffuse reticulonodular pulmonary infiltrates. Cavitations are seen in chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis, and mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy is often present. In immunocompetent individuals, infections may lead to development of granulomas that may or may not be necrotizing.

For laboratory testing, antigen detection in urine or serum using enzyme immunoassays has a sensitivity of 90%6 in disseminated disease and 75%7 in acute pulmonary disease. Antibodies may take 2-6 weeks to appear in circulation and are useful in chronic cases to confirm suspicions of infections but less effective for detecting acute infection and in immunosuppressed patients with a poor immune response.

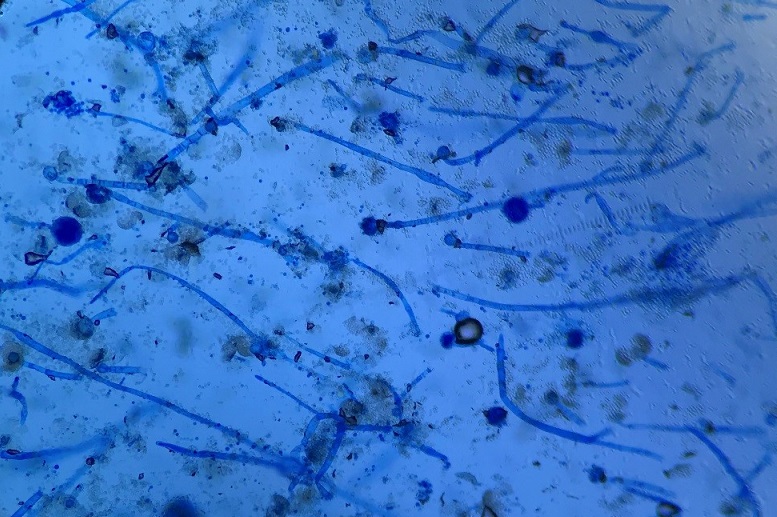

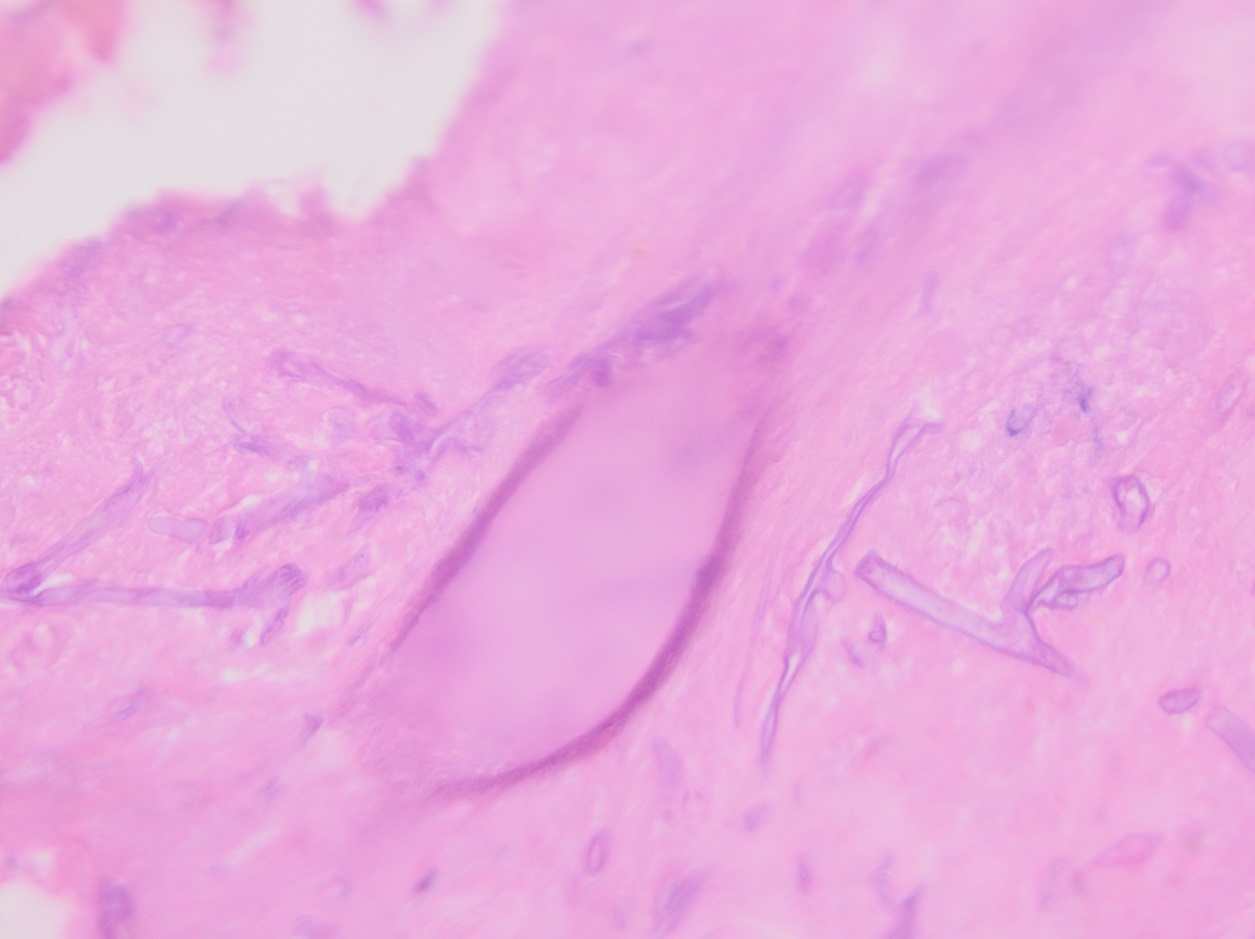

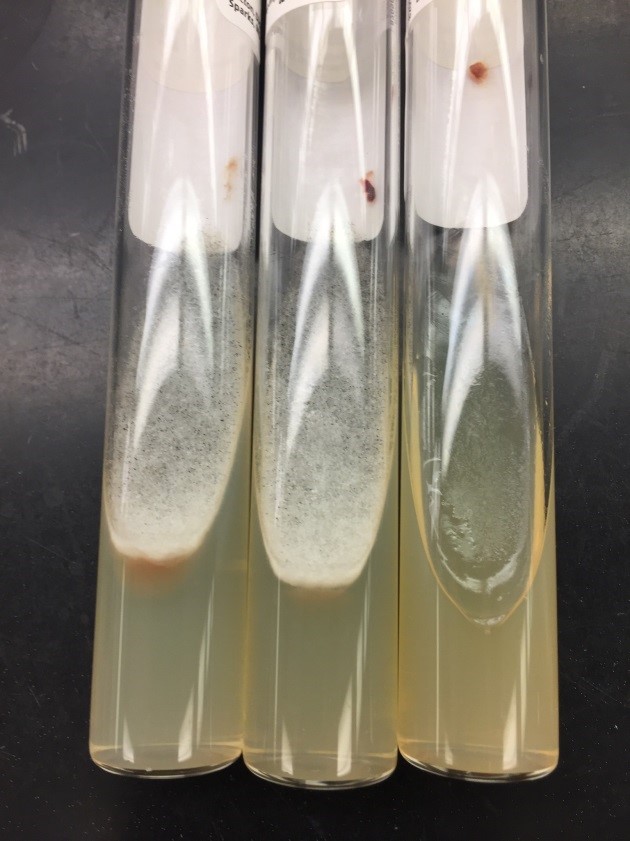

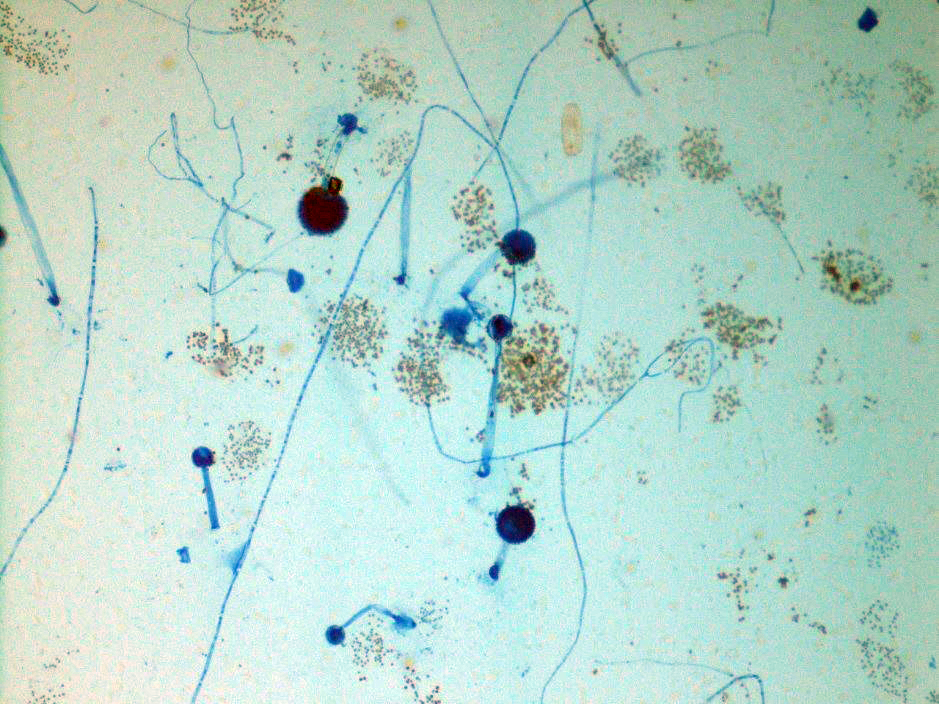

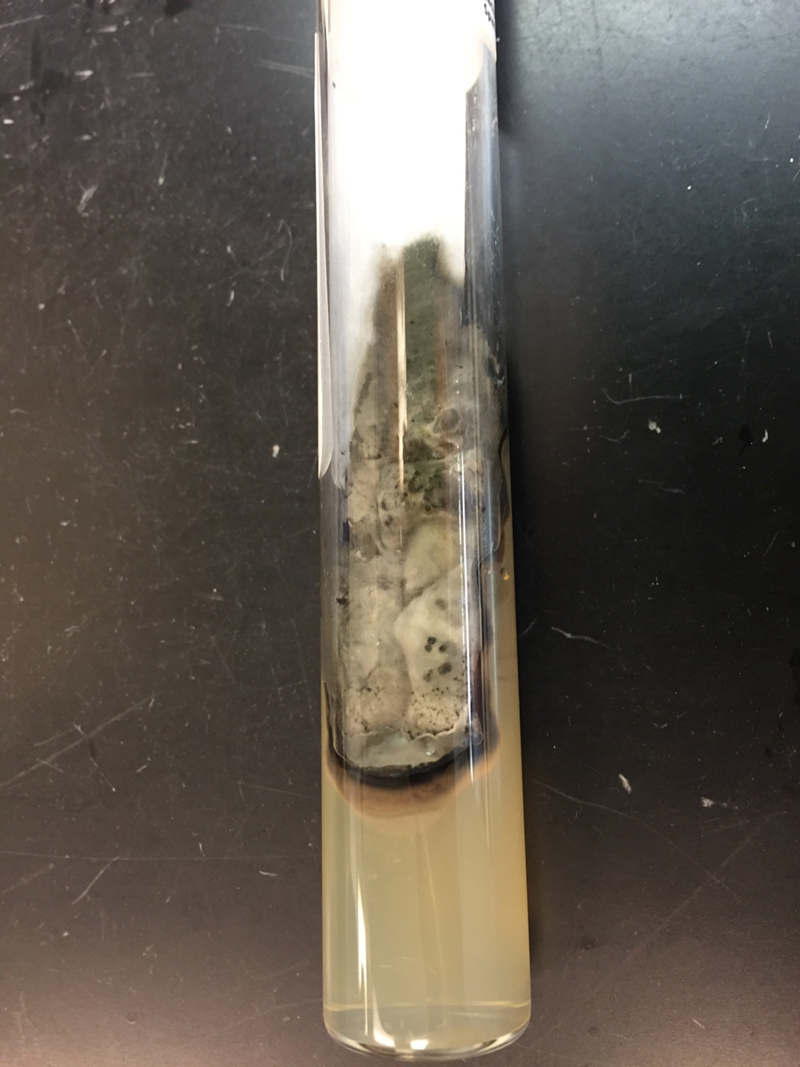

Culturing Histoplasma from clinical specimens is definitive, but it can take 4-8 weeks due to the slow growth of the fungus. The colonies appear white at young growth, have a cottony, cobweblike-aerial mycelium and can mature into brown or grey color on reverse (Figure 1, top) 8. Microscopic examination of mold colony using lactophenol cotton blue preparations reveals the characteristic large, rounded, tuberculate macroconidia (circular structures with roughened/spiked edges) originating from short, hyaline conidiophores (Figure 1, bottom). Histoplasma capsulatum appears as small (2-5 μm), oval, intracellular yeast cells typically found within macrophages. The yeast may exhibit a clear space which may appear like a capsule, but is actually a retraction artifact due to the processing of the specimen. Staining with GMS or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) highlights the yeasts9. Molecular methods such as PCR and sequencing have been shown to detect cases of Histoplasma as well.

Treatment varies depending on the severity of disease. Mild cases, particularly those involving acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, often resolve without specific treatment, although antifungal therapy (e.g., itraconazole) is recommended in more severe cases. For chronic or disseminated histoplasmosis, initial treatment with amphotericin B is often followed by long-term itraconazole therapy. The prognosis is favorable for immunocompetent individuals with mild disease, but disseminated histoplasmosis can be fatal in immunocompromised patients if not treated promptly.

References

- 1. Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, Spec A, Relich RF, Hage C. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):207-27. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.009. PMID: 26897068.

- 2. Bahr NC, Antinori S, Wheat LJ, Sarosi GA. Histoplasmosis infections worldwide: thinking outside of the Ohio River valley. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015 Jun 1;2(2):70-80. doi: 10.1007/s40475-015-0044-0. PMID: 26279969; PMCID: PMC4535725.

- 3. Horwath MC, Fecher RA, Deepe GS Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(6):967-75. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.25. PMID: 26059620; PMCID: PMC4478585.

- 4. Sarosi GA, Voth DW, Dahl BA, Doto IL, Tosh FE. Disseminated histoplasmosis: results of long-term follow-up. A center for disease control cooperative mycoses study. Ann Intern Med. 1971 Oct;75(4):511-6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-75-4-511. PMID: 5094067.

- 5. Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatayavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system. A clinical review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990 Jul;69(4):244-60. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199007000-00006. PMID: 2197524.

- 6. Wheat LJ, Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003 Mar;17(1):1-19, vii. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00039-9. PMID: 12751258.

- 7. Wheat LJ. Laboratory diagnosis of histoplasmosis: update 2000. Semin Respir Infect. 2001 Jun;16(2):131-40. doi: 10.1053/srin.2001.24243. PMID: 11521245.

- 8. Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory Diagnostics for Histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2017 Jun;55(6):1612-1620. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02430-16. Epub 2017 Mar 8. PMID: 28275076; PMCID: PMC5442517.

- 9. Hage, C. A., Ribes, J. A., Wengenack, N. L., Baddour, L. M., Assi, M., McKinsey, D. S., … & Wheat, L. J. (2010). A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(4), 508-512.

-Xingbang Zheng, M.D., was born and raised in Hefei, China. He attended the Peking University Health Science Center, where he received his doctorate degree. He then worked as an OB/GYN physician in China, primarily focusing on female infertility and reproductive surgery. His clinical research concentrated on subtle distal fallopian tube abnormalities and their relationship with endometriosis and infertility. In his free time, Xingbang enjoys swimming, visiting museums, and spending time with his family. Xingbang is currently pursuing AP/CP training.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.