As an unscheduled post, I’d like to make a quick side note separate from public health, zika, and medical school. You may have seen a post I wrote last January about the potential stereotypes and stigmas we might face in laboratory medicine. But, just because we as laboratory professionals operate behind-the-scenes most of the time, we’re still healthcare professionals—and clinician burnout can affect any of us.

I recently watched a video of Dr. Zubin Damania, also known as “ZDoggMD,” a primary care physician and founder of Turntable Health in Las Vegas. He’s a brilliant and passionate doctor with great opinions and an even greater creative sense of humor. Among his many parodies, and “rounds” Q&A questions, ZDoggMD recently had a guest on one of his Facebook shows called “Against Medical Advice” to address the serious issue of suicide and depression in medicine. Janae Sharp was the guest on this episode speaking about her husband, John, a physician fresh into his residency who committed suicide. They go on to talk about her life after this tragedy and how if flipped her and their children’s’ lives upside down. Janae’s described John as a father, a writer, a musician, an idealist, who always wanted to become a doctor. My interest was definitely piqued by this—I tend not to miss most of Dr. Damania’s content—and this is something I’ve been hearing more and more about as my path through medical school continues. But, at one point in the interview my heart just stopped: John was a clinical pathologist. Too close to home, for me at least. I was admittedly surprised.

Pathologist’s don’t have that much stress to make depression and suicide part of that life, I thought. But that is a cold hard assumption. Depression affects so many people at large, and when you’re in healthcare it almost seems like a risk factor on top of issues one might be struggling with. Med school is touted as one of the hardest intellectually, physically, and emotionally grueling experiences you could go through—I will personally vouch for Dr. John and Dr. Damania’s statements about how much these experiences push you to your limits. No sleep, no recognition, no support, fear of failure, imposter syndrome, a wealth and breadth of knowledge that makes you feel like you’re drowning—not to mention that if you do ask for help you’re immediately “lesser” for doing so.

Video 1. ZDoggMD interviews Janae Sharp about her tragic loss, her husband John’s suicide, and the rampant problem of depression and burnout in medicine. Against Medical Advice, Dr. Damania.

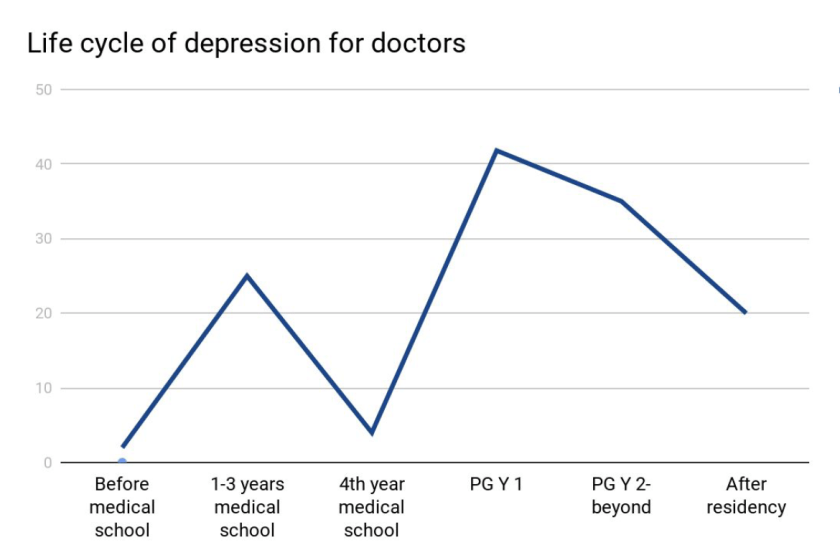

Last month, I was fortunate enough to attend a grand rounds session at my current hospital about this very topic. Presented by Dr. Elisabeth Poorman, internal medicine attending physician, and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School, who talked about how (because of stigmas) medical trainees don’t get the help they need. She demonstrated that prior to med school students are pretty much on-par with their peers with regard to depression. However, once medical school starts, those peers all plummet together as depression rates rise and fall dramatically throughout the various stages of their careers. (I’m just going to go ahead and vouch for this too.) Dr. Poorman shared several case studies that effectively conveyed just how hard it can be when it seems like you are a source of help for many, but no one is there to help you. Story and story recounted the same model of apparent—and often secretive—burnout which ultimately led to a decrease in the quality of care, and in some instances suicide. Dr. Poorman was also brave enough to share her own story. No stranger to depression, herself, it was something that she encountered first hand. She connected herself with this increasingly difficult picture of inadequate support for those of us spending our lives serving others.

There are clear problems facing those of us in healthcare jobs. An ironic consequence, however, of modern scientific advancement is the “doubling time” of medical knowledge. While not necessarily a problem, this refers to the amount, depth, and scope of knowledge physicians and medical scientists are expected to master in order to effectively treat, make critical clinical decisions, and educate our patients. While in 1980 it took 7 years for all medical knowledge to double in volume, it only took 3.5 years in 2010, and in 2020 it’s expected to double every 73 days!1. The problems come as a result of this knowledge because more data means more to do. More time on the computer, higher critical responsibility, and less time to focus on your own mental health all lend themselves to a cyclic trap of burnout. Physicians commit suicide at a rate of 1.5 – 2.3 times higher than the average population.1

Physicians, nurses, clinical scientists, lab techs, administrators, phlebotomists, PCTs—we’re all over worked, under-supported, fall victim to emotional fatigue, and have some of the highest rates for depression, substance abuse, PTSD, and suicide.1 Sometimes, reports from Medscape or other entities will report that burnout is a phenomenon of specialty, hypothesizing that critical nature specialties have more depression than lesser ones2 (the assumption that a trauma surgeon might burn out before a hematopathologist). But truthfully, this is just part of the landscape for all providers. A May 2017 Medscape piece wrote “33% chose professional help, 27% self-care, 14% self-destructive behaviors, 10% nothing, 6% changed jobs, 5% self-prescribed medication, 4% other, 1% pray.”3

So I’m talking about this. To get your attention. So that people reading know they’re not alone. So that people with friends going through something can lend a hand. I’m talking about this. ZDoggMD is talking about this. Jamie Katuna, another prolific medical student advocate, is talking about this. Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is talking about this. This is definitely something we should come together to address and ultimately solve.

What will you do to help?

This was a heavy topic. So in a lighter spirit, I have to share this with all of my laboratory family. If you haven’t heard or seen Dr. Damania’s videos yet, this is the one for you:

Thanks! See you next time!

References

- Poorman, Elisabeth. “The Stigma We Live In: Why medical trainees don’t get the mental health care they need.” Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School. Grand rounds presentation, Feb 2018. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, New York, NY.

- Larkin, Mailynn. “Physician burnout takes a toll on U.S. patients.” Reuters. January 2018. Link: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-physicians-burnout/physician-burnout-takes-a-toll-on-u-s-patients-idUSKBN1F621U

- Wible, Pamela L. “Doctors and Depression: Suffering in Silence.” Medscape. May, 2017. Link: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/879379

–Constantine E. Kanakis MSc, MLS (ASCP)CM graduated from Loyola University Chicago with a BS in Molecular Biology and Bioethics and then Rush University with an MS in Medical Laboratory Science. He is currently a medical student at the American University of the Caribbean and actively involved with local public health.

I’m sitting here at work reading this with tears in my eyes…THANK YOU Mr. Kanakis. This will mean more than words can say to SO many professionals. The silence concerning depression and suicide rates among those in medical professions has been deafening. I, for one, hear you and Dr. Damania (and Mrs. Sharp) LOUD AND CLEAR. Thank you, even through the tears.

Ms. Mozingo,

First of all, thank you for taking the time to read my piece here. I appreciate all the attention and platform to be able to discuss things that matter to me, and I know they matter to many people as well.

This is a serious topic and it’s good to see this being read and shared within our field. Thank you for hearing my words, as well as all the other advocates’ out there. I hear you too and look forward to reaching more people with compassionate colleagues like you.

Take care.