Introduction

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a serious process in which the proteins responsible for clot formation become overactive. It is vital to note that DIC is not a disease in itself, rather it is always secondary to an underlying disorder, which causes over-activation of the coagulation system.1 This over-activation results in activation of coagulation that consumes platelets, clotting factors, and causes microvascular fibrin thrombi, which can lead to organ failure secondary to tissue ischemia.2 The brain, kidneys, liver, and lungs are the most prone to tissue damage in DIC.

Some symptoms of DIC may include bleeding (from multiple sites), blood clots, bruising, hypotension, shortness of breath, fever, confusion, memory loss, or behavior change.3 Patients always present with symptoms of other disorders frequently associated with DIC such as sepsis, trauma, liver disease, obstetric complications, and malignancy to name a few. In most cases, coagulation does not result in clinical complications, and is not evident until the consumption of platelets and factors becomes overwhelming.1 Once there is overwhelming consumption, it becomes visible through prolonged clotting tests and increasing thrombocytopenia.1 Therefore, timely recognition is crucial in recognizing DIC.

A major challenge of both prognosis and management, of DIC is that it is not a single disease entity. Prognosis largely depends on the treatment of the underlying condition, as the condition is what drives the activation of the coagulation cascade. Treatment is generally supportive, and entails supporting various organs. Support may include the use of ventilators, hemodynamic support, or transfusion of blood components. As well, algorithms have been developed to help guide the management of patients with DIC.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old female presented to the emergency department with complaints of bleeding gums, bruising all over her body, and recurrent nosebleeds for longer than a week. The patient has a history of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL/AML-M3), and has had symptoms of gingival bleeding, widespread ecchymosis, and recurrent epistaxis for longer than a week. Past fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of the patient’s bone marrow aspirate revealed a t(15;17) translocation. Bone marrow studies also showed blast cells with granulation, dysmyelopoiesis, and 60% promyelocytes with the presence of Auer rods. Immunophenotyping was negative for expression of CD34, and positive for expression of CD13 and CD33. Cytochemical staining tests were positive with myeloperoxidase (MPO), Sudan Black B (SBB), and specific esterase (SE), and negative with non-specific esterase (NSE). As well, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed the PML-RAR(alpha) fusion gene, consistent with a diagnosis of AML-M3.

The patient has undergone one past treatment of retinoic acid, as well as traditional chemotherapy. It should be noted that some studies indicate a higher incidence of DIC in acute leukemia patients during remission induction with chemotherapy.1 The patient has no family history of the disorder/condition. There are no occupational or social implications/factors, but it is associated with a specific genetic mutation. The patient has no known drug allergies.

Vital signs were normal upon arrival. Upon physical examination, the patient appeared pale and lethargic, displayed widespread ecchymosis, and swollen gums.

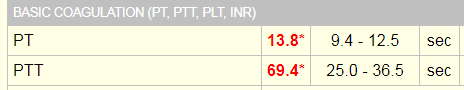

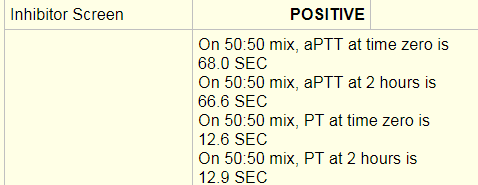

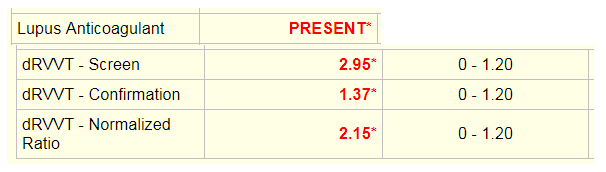

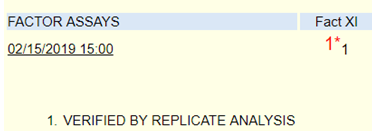

Laboratory tests revealed a decreased hemoglobin concentration of 6.0 g/dL (normal, 12.0-16.0 g/dL), and an increased white blood cell (WBC) count of 19.5 x 109/L (normal, 4.5-11.0 x 109/L). The WBC differential showed 91% promyelocytes with heavy granulation, 3% myelocytes, 4% metamyelocytes, and 2% neutrophils. Platelet count was decreased at 72,000/uL (normal, 150,000-450,000/uL). Prothrombin time (PT) was prolonged at 22 seconds (normal, 10-13 seconds) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was prolonged at 54 seconds (normal, 23-36 seconds). D-dimer concentration showed an increase at 12 ug/mL (normal, <0.5 ug/mL), and a decreased fibrinogen concentration of 60 mg/dL (normal, 200-400 mg/dL). Plasma levels of plasminogen were 65% (normal, 80-120%), and plasma levels for a2-antiplasmin were 46% (normal, 80-100%). These findings are consistent with DIC with marked hyperfibrinolysis, as correlated by low levels of a2-antiplasmin and plasminogen. The patient was diagnosed as having symptoms associated with DIC secondary to AML-M3.

The treatment for this patient included avoidance of all invasive procedures including biopsies or intravenous (IV) line placement, as the patient was at high risk for bleeding. Likewise, due to the high risk of bleeding, the use of heparin as a supportive therapy was not advocated. The patient received a platelet transfusion, with an aim of a platelet count greater than 50 x 109/L. As well, the patient received fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and fibrinogen concentration, guided by the concentration in the patient’s plasma. Supportive treatment will continue to be maintained during remission induction of AML-M3, and the disappearance of the coagulopathy.

Discussion

The typical symptoms of DIC are generally those of the underlying process, which incites the condition. Underlying conditions may include, but are not limited to, severe infection with any microorganism, sepsis, trauma, solid tumors and malignancies, hepatic failure, and obstetric complications.4 Acute DIC may present as ecchymosis or petechiae. Additionally, there is usually a patient history of bleeding such as gastrointestinal or gingival bleeding.4 Post-operative DIC patients can also experience bleeding from various surgical sites, or within serous cavities.5 One should remain cognizant of signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), as well as microvascular thrombosis. One hallmark of DIC is bleeding from at least three unrelated sites.4 Chronic DIC may present as thrombosis due to excess thrombin formation. Patients with comorbid liver disease may also present with jaundice, while patients with pulmonary involvement may present with a cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis.4

Epidemiology

DIC occurs in all ages and races, and has not been shown to have a predisposition for a particular gender.4 DIC has been known to develop in about 1% of all hospitalized patients.4 DIC accounts for 9%-19% of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions.2 Although assigning values to DIC-related morbidity and mortality proves difficult, studies show it occurs in roughly 35% of septic patients.1 In a trauma setting, the presence of DIC may often double the mortality rate.4 DIC may be diagnosed in roughly 15% of patients with underlying acute leukemia.1 Previous studies report the occurrence of major bleeding to be 5%-12%, although patients with a platelet count of less than 50 x 109/L show a higher risk for bleeding when compared to patients with increased platelet counts.1 The occurrence of thrombosis in both small and midsize vessels is more commonly seen, which contributes to organ failure. Overall, the severity of DIC is directly related to increased mortality, thus emphasizing the importance of early recognition.

Related Disorders/Conditions

Several conditions are known to be complications of DIC. These conditions include, but are not limited to, kidney injury, altered mental status, respiratory dysfunction, hemothorax, gangrene, digit loss, and shock.4 In most cases, the release of tissue material into circulation in conjunction with endothelial disruption, leads to the activation of the coagulation cascade.

Pathophysiology

In DIC, the patient’s underlying condition stimulates powerful procoagulant activity that results in excess thrombin. The excess thrombin then overcomes the anticoagulant control mechanisms of protein C (PrC), antithrombin (AT), and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), allowing for widespread thrombosis throughout the vasculature.2 The patient paradoxically battles between an excess thrombin state due to thrombin, embolism, and microvascular occlusion, and a hemorrhagic disorder secondary to depletion of platelets, consumption of coagulation factors, and accelerated formation of plasmin.2

To fully understand DIC, one must review normal hemostasis. Normal hemostasis generally takes place in response to an injury to the blood vessel wall. In normal hemostasis, a well-maintained process takes place in three stages: primary hemostasis, secondary hemostasis, and fibrinolysis. Primary hemostasis results in formation of the primary platelet plug via platelet adhesion, aggregation, and secretion.6 Secondary hemostasis is responsible for the formation of fibrin, and involves plasma proteins. In secondary hemostasis, fibrinogen is converted to fibrin, which forms a mesh that acts to reinforce the primary platelet plug, thus forming a hard, more stabilized clot at the site of injury, stopping any active bleeding.6 Finally, fibrinolysis takes place. Fibrinolysis is the process of the removal of fibrin through proteolysis, so that normal vessel structure and function can be restored.6 As part of normal healing, in response to an injury, clotting should only occur as a localized phenomenon, as there are many checks and balances to prevent extension of the hemostatic plug mechanism to the entire intravascular system.2 In DIC, this process of hemostasis runs out of control.

Laboratory Tests and Applications

Since DIC is secondary to an underlying disease, its diagnosis can be challenging, as there is no single laboratory test with sufficient accuracy to allow for a diagnosis. Imaging studies are generally only useful in detecting the underlying condition inciting DIC.4 DIC may present with a wide range of abnormalities in laboratory values. Laboratory findings of thrombocytopenia, prolonged coagulation times, decreased fibrinogen, elevated fibrin degradation products (FDPs), and elevated D-dimer levels are indicative of DIC.4 A complete blood count (CBC) and peripheral blood smear may show moderate-to-severe thrombocytopenia, as well as the presence of schistocytes secondary to evidence of microangiopathic pathology.4 Additionally, scoring systems have been developed to aid in diagnosis of DIC.4 The International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) developed a scoring system that makes use of laboratory tests, and a DIC score calculator. However, it is important to note, the presence of an underlying condition frequently associated with DIC is essential for the use of this diagnostic algorithm.4 Studies have reported the sensitivity of the DIC as 93%, and the specificity as 98%.4 As well, this scoring system has shown to be a strong predictor for mortality in sepsis. Similar scoring systems have been developed in other countries as well. Other conditions that may be ruled out by these tests include thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), chronic liver disease, Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), and Coumadin/Vitamin K deficiency.2

Correlation of Laboratory Tests

Thrombocytopenia is the most common laboratory finding in DIC, reported in 93% of cases.5 In many cases, the thrombocytopenia may not yet be severe; therefore, it is crucial to recognize a downward trend in platelet count despite a recent count in a normal range.5 Acute DIC typically presents with a rapid consumption of platelets and clotting factors, so that at the time of diagnosis, the platelet count may be less than 50 x 109/L, the PT and aPTT values are markedly prolonged.2 FDPs appear elevated, as they are released into circulation as the body attempts to break down clots. Fibrinogen levels may be decreased, as it is used up. Likewise, plasminogen and AT show a decrease.2 D-dimers appear increased as a result of fibrinolysis and excess plasmin.2 Red blood cells (RBCs) that are pushed through occluded vessels in the microvasculature become fragmented and will often appear on a peripheral blood smear as schistocytes.

Impact of Pathophysiology on Laboratory Results

DIC can present with a variable range of abnormal laboratory values. Additionally, the values may only represent a momentary glimpse into a rapidly changing systemic process and often requires frequent repeated testing.4 As well, patients with chronic DIC may present with only minimal abnormalities in laboratory tests. There is no single test that is a specific indicator for DIC. Rather, the use of combined tests such as platelet count, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, and D-dimer, in conjunction with an underlying disorder, help guide management and treatment.

A diagnosis of DIC is reached only through a combination of the clinical impression in conjunction with laboratory abnormalities.5 The patient history plays a significant role in that DIC is always secondary to an underlying condition, therefore the clinical presentation of DIC will be the features of the primary disease.

Treatment

The treatment of DIC typically involves focusing on the underlying disorder, as manifestations of DIC will subside once the underlying condition is addressed. Management of DIC itself follows four basic features: monitoring vital signs, assessing and documenting the extent of thrombosis and hemorrhage, correcting hypovolemia, and administering basic hemostatic procedures when indicated.4 Therapeutic interventions are mostly supportive in nature, and may include transfusion of blood components including platelets and clotting factors. However, blood components should be reserved for those patients who have hemorrhage, require a surgical procedure, or pose a high risk for bleeding complications.2 The use of heparin is usually reserved for cases of chronic DIC, and should be provided to patients demonstrating widespread fibrin deposition without evidence of substantial hemorrhage.4 Generally, the use of antifibrinolytic drugs should be avoided, as they have been known to cause thrombotic complications, although these agents have proven useful in cases associated with AML-M3 and other types of cancer.4 In these cases, Heparin should always be administered with antifibrinolytic drugs so as to arrest any prothrombotic effects.4 In patients with trauma and massive blood loss, antifibrinolytics such as tranexamic acid has shown to be effective in reducing blood loss and improving survival.4 Only minimal cases have been reported to benefit from administration of activated PrC.

Patient Response to Treatment

Treatment decisions for this patient are based on clinical and laboratory evaluation of hemostasis. The patient is to avoid all invasive procedures such as IV-line placement and biopsies. Heparin, in this case, is contraindicated secondary to bleeding risk. The patient received FFP, platelets, and fibrinogen concentrate. The patient currently remains hemodynamically stable, however, if evidence of significant bleeding and hyperfibrinolysis remains, tranexamic acid may be administered in conjunction with heparin. Clinical and laboratory parameters will continue to be monitored every eight hours.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with DIC depends on the severity of the coagulopathy, as well as the underlying condition that incited DIC. Generally, if the underlying condition is self-limiting or can be appropriately managed, DIC will disappear, and coagulation status will return to normal.4 Since DIC is a complex process, it is crucial to monitor the patient for clinical improvement or worsening, as well as to identify the early development of possible complications.

Treating the underlying AML-M3 is critical for the prognosis and management of this patient. The patient is encouraged to regularly consult with a hematologist for assistance with management of DIC, as chronic DIC may be treated on an outpatient basis after stabilization.4 Chronic DIC in patients with cancer may be managed with low molecular weight heparin or subcutaneous heparin. As well, other subspecialty consultations are necessary as indicated by the patient’s primary diagnosis.

Conclusion

DIC is not a specific illness, rather, it is a complication or an effect secondary to the progression of other underlying illnesses. It is associated with numerous clinical conditions, which involve excessive activation of the coagulation system.

Although interventions are supportive, they have been shown to be only partly effective. Since the clinical course of DIC ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening, understanding its pathogenesis is vital for early recognition. Despite diagnostic criteria to aid physicians in the management of patients with DIC, newer laboratory markers and treatment modalities are warranted to improve patient outcome.

References

1 Levi M, Scully M. How I treat disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood. 2018 Feb 22;131(8):845-54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-804096

2 Boral BM, Williams DJ, Boral LI. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Am J of Clin Pathol. 2016 Dec;146(6):670-68. doi: 10.93/AJCP/AQW195

3 Medline Plus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); updated [date]. Disseminated intravascular coagulation; [updated 2022 Mar 21; reviewed 2019 Sep 24; cited 2022 Mar 30]; [about 2 p.] Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000573.htm

4 Levi MM, Schmaier AH. Medscape [Internet]. Emedicine; [2020 Dec 06; 2022 Apr 22]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/199627-overview

5 Thachill J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: A practical approach. Anesthesiology. 2016 Jul;125(1): 230-6. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001123

6 Rodak BF, Fritsma MG, Fritsma GA. Normal hemostasis and coagulation. In: Hematology: Clinical principles and applications. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. p. 626–44

7 Hussain SA, Zafar A, Faisal H, Vasylyeva O, Imran F. Adenovirus-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation. Cureus. 2021 Mar 30;13(3)e14194. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14194 8 Onishi T, Ishihara T, Nogami K. Coagulation and fibrinolysis balance in disseminated intravascular coagulation. Pediatr Int. 2021 Nov;63(11):1311-18. doi: 10.1111/ped.14684

-Kaysi Bujniewicz, MLS(ASCP)CM graduated Magna Cum Laude from University of North Dakota School of Medicine with a Bachelor of Science in Medical Laboratory Science. She has worked in clinical laboratories for over eight years as a certified and licensed Medical Laboratory Technician and a Medical Laboratory Scientist. Although her true callings are in Immunohematology and Clinical Microbiology, she currently works as a Generalist.