When the Medical Examiner’s office receives a report of someone dead in a bathtub, the reporting party often presumes that the individual must have drowned. Yet deaths in bathtubs can be surprisingly complex. We initially discussed drowning back in June of 2023 but to summarize, drowning is a diagnosis of exclusion. The few signs of drowning at autopsy (pulmonary edema, watery fluid in the stomach and sinuses), are neither sensitive nor specific, so it is critical to exclude other potential causes of death. Particularly when a bathtub (or hot tub) is involved, a methodical step-by-step approach is helpful to avoid jumping to inaccurate conclusions.

The first step for us is to determine if the tub contained water. While this may sound obvious, this critical detail isn’t always reported initially. The first person on scene often reflexively turns off running water and opens the drain – and (understandably) in the heat of the moment, this alteration of the scene might not be documented. Our investigators are experienced at identifying indirect evidence of a wet bathtub, such as a water line, wet clothing, or wet sponges and washcloths.

Simply having water in the tub isn’t sufficient, though. We need to know whether the person’s nose and mouth were beneath the water. Sometimes, the physical dimensions of the tub and the position in which the person was found are incompatible with complete submersion. If the body has been moved, though, this evidence may be lost. Conversely, just because someone’s face is under the water doesn’t prove that they drowned; someone may die suddenly from heart disease while filling the tub, for example, and subsequently the water rises.

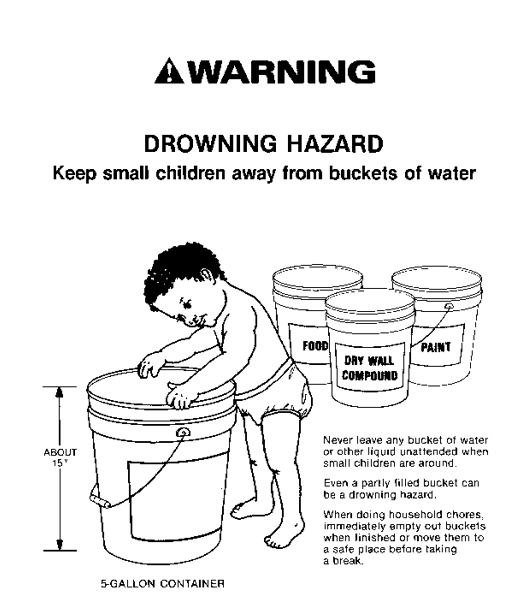

As mentioned earlier, there are no pathognomonic signs of drowning at autopsy. This isn’t necessarily a problem in the proper context. Take this example: a person who doesn’t know how to swim (and isn’t wearing a flotation device), falls out of a boat into a natural body of water. The body is recovered a day later. An autopsy reveals no “typical” drowning findings, but no other potential causes of death. In this scenario, drowning is the only remaining reasonable option for a cause of death. But to diagnose drowning in a shallow body of water, we need to explain why the person couldn’t escape the environment. In other words, in a bathtub, why didn’t the decedent just sit up? Sometimes, the reason is the age of the deceased – infants or young toddlers clearly can’t escape a deep bathtub, but even large buckets can be dangerous if they fall head-first (figure 1). Elderly and frail individuals, or those with neuromuscular conditions, may be unable to pull themselves up to a sitting position. Conditions like epilepsy can be dangerous if a seizure occurs while the person is bathing, and intoxication by alcohol, opiates, or other sedative-hypnotic drugs may cause someone to lose consciousness and slip beneath the water.

As you can see, there are a lot of avenues for interrogation investigating a death in a bathtub. That’s why these cases can be excellent examples of forensic casework – the correct answer is only identified following thorough scene investigation, autopsy, toxicology, and a review of the medical history.

References:

United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. “Large Buckets are Drowning Hazards for Young Children”. Originally published 07/12/1989. Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/Newsroom/News-Releases/1989/Large-Buckets-Are-Drowning-Hazards-For-Young-Children

-Alison Krywanczyk, MD, FASCP, is currently a Deputy Medical Examiner at the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office.