Patient History

A 72 year old Caucasian man with diabetes presented to his primary care physician in late September complaining of recent extreme fatigue while baling hay on his farm in southern New England. A thorough interview revealed recent anorexia with a 15 pound weight loss, dyspnea on exertion, joint pain and easy bruising. Blood work demonstrated pancytopenia with 17% blasts on peripheral smear. Further work-up established a diagnosis of acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AML) and the patient was started on chemotherapy. During his admission, he spiked a fever (101°F) and based on a chest x-ray showing a left basilar consolidation was consistent with pneumonia and he treated with vancomycin and Zosyn. Symptoms persisted despite the addition of acyclovir and anidulafungin. Given an infectious etiology was continually suspected based on a chest CT showing right upper and left lower lobe opacities, infectious disease (ID) was consulted.

The detailed ID work-up noted an exposure history including interaction with chickens and cows, though the veterinarian reported that the livestock were avian flu negative and vaccinated against brucellosis, respectively. Further, it was revealed that the farmer’s hay had recently been infested with voles and that mold had been found growing in his home and barn. ID recommended a bronchoscopy and a CT-guided lung biopsy to characterize the patient’s pathology more completely. The patient remained febrile (102.9°F) and his condition deteriorated to the point of requiring MICU admission. A new chest CT showed rapid progression of airspace opacities.

Gross findings from the bronchoscopy raised concern for an invasive fungal infection but all specimens obtained for cytology and culture were negative for a fungal process. The patient continued to decline with multisystem organ failure, the development of new hypoechoic liver lesions on ultrasound and a brainstem mass without evidence of herniation on head CT. His fever peaked at 106.2°F at which time he was transitioned to comfort measures only and passed away shortly after.

Pathology Identification

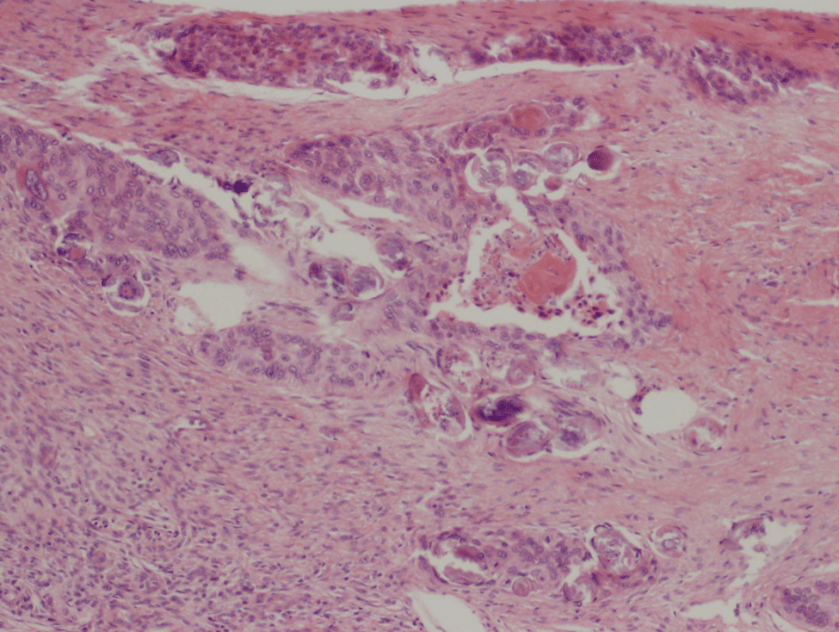

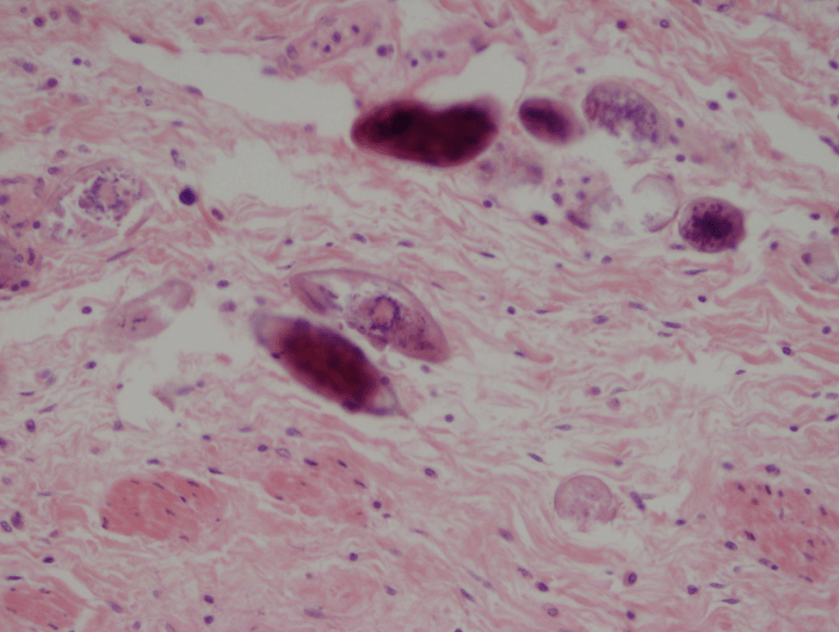

Post-mortem, a limited autopsy was performed and gross, histologic and special stains finding are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Gross and histologic lung images from autopsy. Target shaped lesions on the lung surface can be seen in this gross photograph of the upper and middle lobes of the right lung in situ (A). A sample of lung parenchyma was sectioned and H&E staining revealed broad, irregularly branched, pauci-septate fungal elements admixed with a brisk inflammatory infiltrate within damaged alveoli (B). Depiction of angioinvasion as the fungal organisms penetrate the walls of pulmonary vessels; GMS and PAS fungal stains, respectively (C and D).

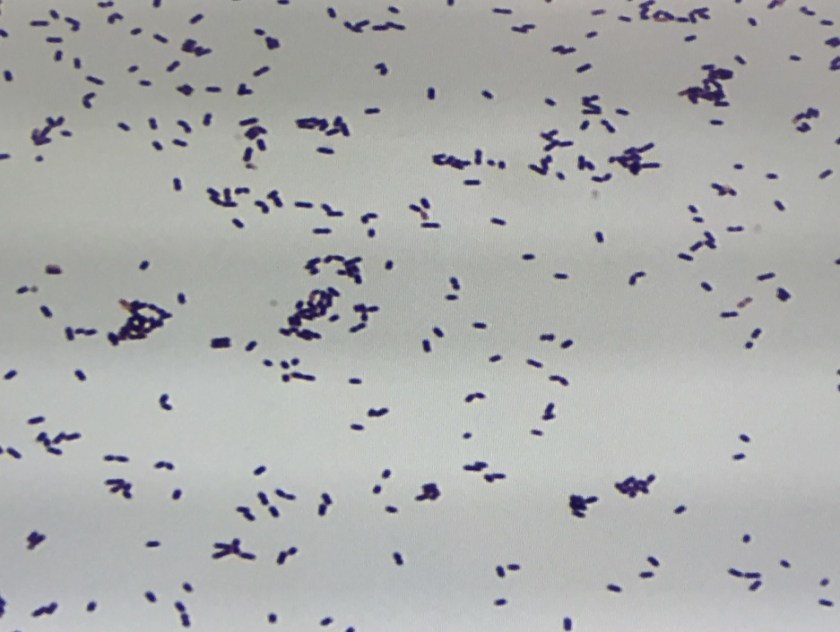

Grossly, both lobes were abnormal. Specifically, as seen in Figure 1A, the right upper lobe exhibited multiple target shaped lesions on its surface in addition to a thin fibrinous coat involving the visceral and parietal pleurae. Moreover, the right upper lobe was adhered to the chest wall. Histologic examination of the lesions demonstrated abundant inflammatory cells and board fungal hyphae that were irregular and “ribbon like” with occasional septations within the disrupted lung parenchyma and invading into blood vessels as seen in Figure 1B-D. Tissue from the lung lesions were cultured at autopsy and grew Lichtheimia spp.

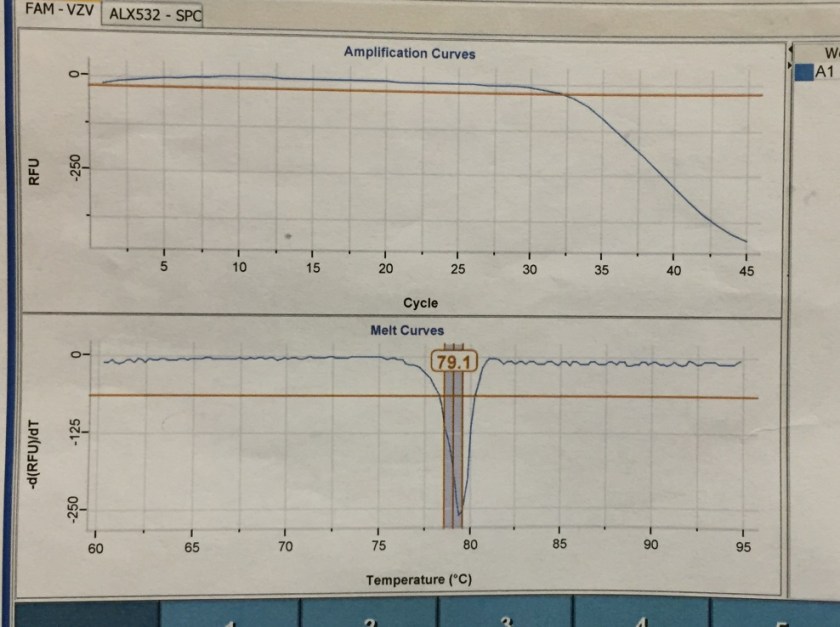

A battery of additional tests collected premortem for Streptococcus pneumoniae, Cryptococcus neoformans, Mycoplasma, Histoplasma, Blastomyces and Toxoplasma gondii were all negative. The AFB culture from the BAL specimen grew Mycobacterium avium after 8 weeks of incubation.

Discussion

Lichtheimia is a fungal genre, which shares the order Mucorales with variety of other clinically relevant organisms including Rhizopus, Rhizomucor and Mucor. It was formerly referred to as Absidia and many resources still use this term. As a saprophyte, Mucorales species live freely in the environment and can often be found indoors as well as outdoors. In the healthcare setting, infections are most frequently encountered in diabetic patients. In fact, along with its other Mucorales relatives, Lichtheimia spp. demonstrate a particular tropism for high glucose environments. Immunosuppressed individuals, especially those with hematologic malignancy, are also commonly infected with the fungi of this order – an observation, which speaks both to the ubiquity of these organisms in the human environment as well as the crucial role played by the immune system in their control. Today, the infection caused by Lichtheimia and its relatives is referred to as mucormycosis, though the related term zygomycosis remains deeply ingrained in the medical lexicon. The most striking presentations of mucormycosis are those involving the rhino-orbital-cerebral tissues. However, Mucorales organisms can also colonize many other organ systems. Relevant to this case, pulmonary mucormycosis is a particularly severe form of the infection with a mortality rate nearing 90%. Further, in a patient with pulmonary mucormycosis, the likelihood of concomitant disseminated mucormycosis is also very high (nearing 50%). Though in the present case the post-mortem examination was limited to only particular lung lobes, clinicoradiographic findings preceding the patient’s death strongly suggested that the infection also involved the liver and brain.

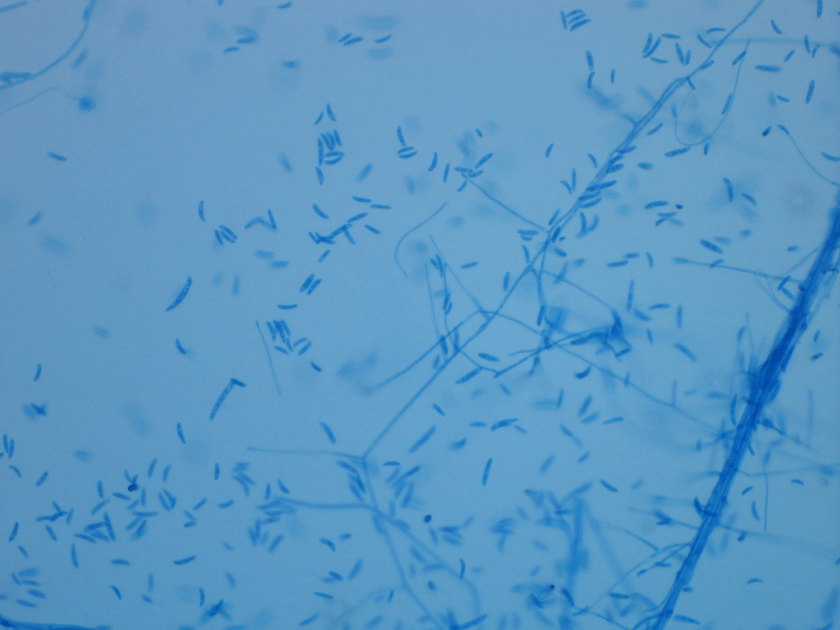

Diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis can be tricky and often hinges upon histopathologic findings and culture results. As in the present case, Mucorales organisms are differentiated from other common fungi with similar presentations based on their broad hyphae with limited septations and irregular branching. By contrast, Aspergillus spp. exhibits more narrow hyphae with septations and regular, acute-angle branching patterns. Additionally, Mucorales organisms, like Lichtheimia, are often angioinvasive and histologic examination may demonstrate fungal elements entering vascular lumina and even inducing thrombotic infarctions (both noted in the current case). In the laboratory, if a Mucorales is in the differential diagnosis, the tissue specimen should be minced instead of ground in order to preserve viability of the organisms. Mucorales grow rapidly as non-descript, whitish-gray molds within 4 days and are described as “lid lifters” due to their predilection to completely fill the plate. Due to its highly infectious nature, plates should be wrapped in parafilm and only examined in certified biosafety cabinets. On a lactophenol cotton blue prep, the sporangiophores of Lichtheimia and Rhizomucor spp. arise internodally between the rhizoids. This is in contrast to Rhizopus spp. in which the sporangiosphores arise directly over the rhizoids and Mucor spp. where rhizoids are not produced.

While there is little doubt that the patient in the above case was particularly susceptible to environmental Lichtheimia spores as a consequence of his immunosuppressed condition and status as a diabetic, the contribution played by his occupational exposures is less clear. Though provocative, it would be challenging to establish a link between the patient’s terminal infection and his agricultural encounters with decaying vegetable matter and the associated molds.

-JP Lavik, MD/PhD, is a 3rd year Anatomic and Clinical Pathology Resident at Yale New Haven Hospital.

-Lisa Stempak, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. She is certified by the American Board of Pathology in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology as well as Medical Microbiology. She is the director of the Microbiology and Serology Laboratories. Her interests include infectious disease histology, process and quality improvement and resident education.