Nichole Baker, PA, works at Mercy Regional Medical Center in Durango, Colorado as a Pathologists Assistant. Nichole started working as a volunteer with Mbarara University of Science Technology (MUST) in 2017 through the existing partnership with Massachusetts General Hospital Pathology department– she responded to an advertisement looking for pathology volunteers that Dr. Drucilla Roberts had placed in a pathology journal. She decided to visit the laboratory and see in what ways she could help. In total, she has visited three times, and in that time, has accomplished incredible things! What was particularly impressive to me is that Nichole single-handedly solved a very complex problem in the MUST laboratory. In fact, it was this same problem that many people (including myself!), had attempted to solve and could not find the means to do so! Not only did she implement a solution to the problem, but she did it in just two weeks!

Read on to hear from Nichole about her experience making positive changes in her global community. I guarantee you will be inspired by her work, her enthusiasm, and her can-do attitude!

Q: Nichole, I know that you recently returned from Uganda, and you were able to team up with the pathology staff at MUST to make some major changes and implemented a solution to a major problem. Can you tell me about your project?

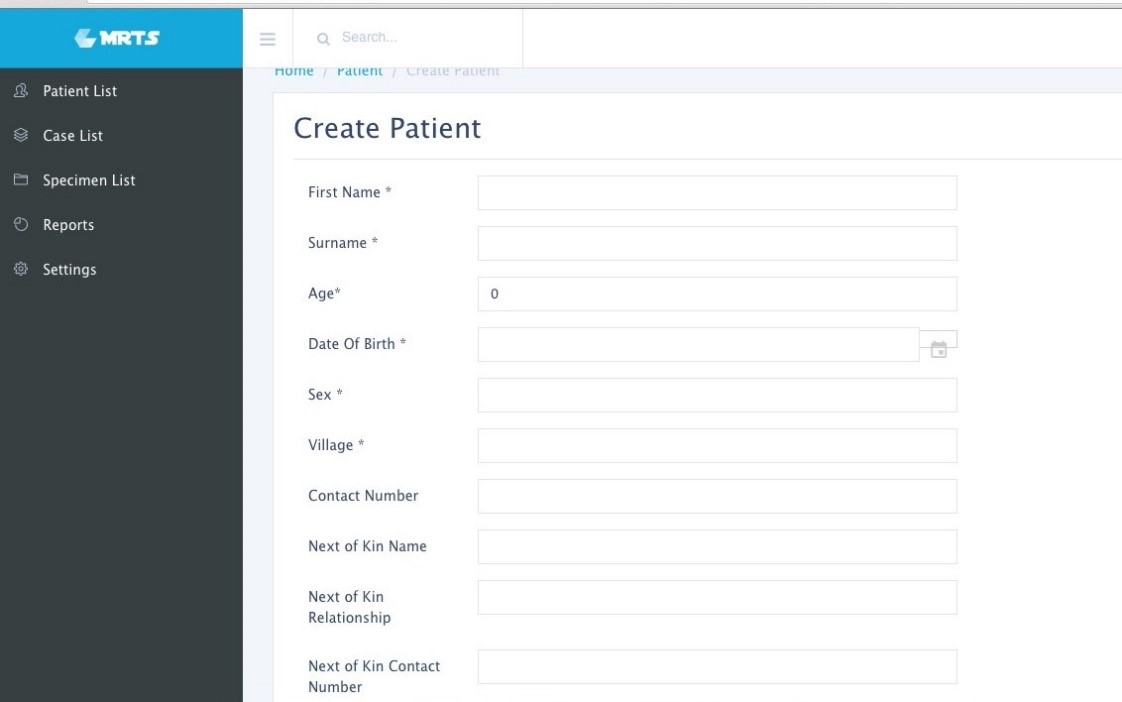

A: It started with realizing from my two prior visits to the anatomic pathology lab at MUST that the laboratory had a faulty internal tracking system for cases. This had two consequences: The first is that the case turn-around time has been very difficult to track. This even results in occasional cases being lost entirely. The second is that there is no repository of cases to be able to easily conduct research.

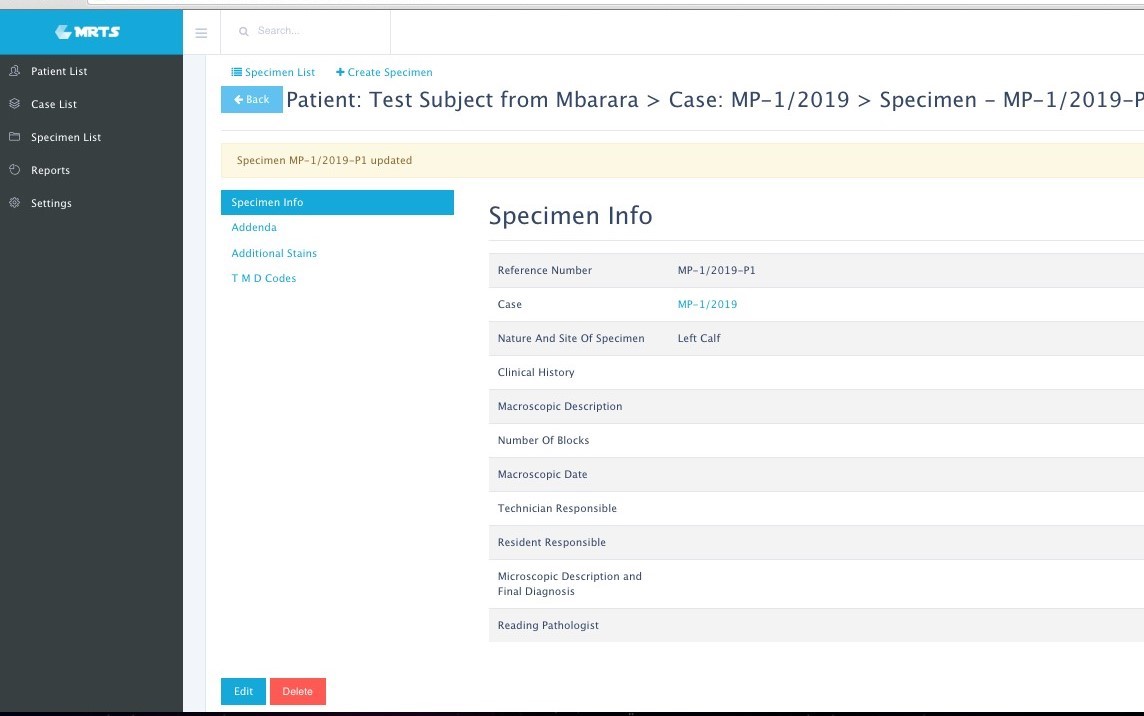

What I decided to do was build a free computer program that could accession the cases, track them, generate a pathology report, and give a report of turn-around-time. Not having a computer science background myself, I contacted a friend who connected me with a software engineer in Denver, Colorado. He helped guide me in what would be feasible to accomplish and helped me find a pro-bono programmer based in Belize named Maurice, who had some background in healthcare IT. We started building the system less than a month away from my departure to Uganda.

My goal was to work with the laboratory staff to build a program based around their needs, for which I needed to be there in person to clearly identify – I set out on my third trip in March 2019, this time for two weeks. Maurice and I built a cloud-based tracking program and every day, we would try it out in the laboratory. Day by day, issues would arise, such as the need to add a sign-out function, general localization changes, or adding a timestamp for a particular function. Fortunately for me, Maurice and I had a substantial time difference which really worked to our advantage. I would try the system out during the day and then email Maurice a report that he would just be waking up to. He was able to work in Belize while we were asleep in Uganda, and when I returned to the lab the next day, the program had been updated with the changes. This allowed for rapid progress and the pathology staff grew more and more excited to use the system as it improved. So, day by day, we made the program better and better.

Q: What were some of the unique challenges that you faced when implementing the program?

A: Originally, we had planned to use a laptop with boosted RAM to act as a local server, but the network in the hospital wasn’t functioning as needed. On-site we realized we’d need to shift to an internet server and to do so we had to improve the internet access in the laboratory in order to run the program –this was difficult because IT progress can be slow in Uganda.

Another example that is unique to this setting is the difficulty we had in generating unique patient identifiers in the registration system. In the US, two patient identifiers are required for each sample, and that is easy to obtain because everyone knows their date of birth. In Uganda, things are not as clear and straightforward. We might only have the village they live in, or a phone number. We had to look to see what items were most consistently reported and use those.

Q: How are you financing the data storage and internet?

A: All fees and costs associated with the program were raised by a small charity organization I started in 2017 called “Path of Logic” which has 501c3 status, making any donations tax deductible. With the funds raised, a shared laboratory laptop was purchased. We are using a cloud-based system that charges based on storage space. Right now, the storage need is low because reports are stored as PDFs, but we may need to expand in the future. The internet connection is also a low expense, as it’s simply a backup modem that’s used when the university internet is not functioning.

Q: It’s now been two months since you rolled out the program in the lab. What results have you seen from that?

A: Once we got going, we have been able to identify where the delays were in processing the cases. After I returned back to the US, Maurice and I continued to work on small issues remotely, such as single vs. double click preferences and those sorts of things.

So far, 421 cases have been registered in the system. The average turnaround time is 12.5 days. We still have a lot of work to go, but this is the first we’ve been able to track this number. Many of the cases that were started in the weeks following my departure were not signed out, but as the team sees the value in the system, the more accurate that average will be, allowing adjustments to be made accordingly.

We also added in the ability to assign ICD codes to the final diagnosis to allow for a way to categorize the cases to make the diagnosis searchable. Now we are going to be able to generate epidemiological data. This feature is not yet in use by the pathology team, but we are hopeful that as the system becomes more routine, this will be the next step to incorporate.

Q: What future impact do you think this program might have?

A: In addition to being able to easily track cases, build pathology reports, generate icd codes for researching cases more easily, we also hope that this will eventually result in increased funding for pathology services in Uganda. Right now, the money allocated from the Ugandan Ministry of Health is going towards HIV, malaria, and cancer treatment – but not for diagnostics. The Department of Education allows some funds for Pathology, but only about 30% of what is needed. Part of the reason why is that until now, there has been no way to quantify the number of cancer cases. With our program, we will be able to generate that data to show real numbers when lobbying for increased funds.

-Dana Razzano, MD is a Chief Resident in her third year in

anatomic and clinical pathology at New York Medical College at

Westchester Medical Center and will be starting her fellowship in

Cytopathology at Yale University in 2020. She was a top 5 honoree in

ASCP’s Forty Under 40 2018 and was named to The Pathologist’s Power List

of 2018. Follow Dr. Razzano on twitter @Dr_DR_Cells.