I like to think most people who go into healthcare professions do so with the hope of helping others. For those of us who do autopsies, the greatest sense of reward comes when we can explain to someone how and why their loved one died. Inevitably, though, there will be situations where we need to accept what we don’t know – despite how disappointing it may be. In these situations, the most intellectually honest course of action is to issue a manner of “undetermined.”

Let’s recap briefly what we know about manners of death (see https://labmedicineblog.com/2022/11/25/please-dont-tell-me-i-died-of-cardiac-arrest/ for a more in-depth discussion). Manner of death describes the circumstances in which the cause of death is sustained, and there are five choices in most jurisdictions – natural, accident, homicide, suicide, or undetermined. Natural deaths are those due entirely to non-traumatic diseases (like cancer or coronary artery disease). Accidental deaths involve trauma or toxicity without an intention to harm. Homicide is death at the hands of another person, whereas suicide is death at one’s own hands. The final option is undetermined.

There are two main pathways by which we can arrive at an “undetermined” manner. There can either be 1) reasonable competing evidence between two manners of death, or 2) we may be unable to identify a cause of death due to loss or destruction of bodily tissue. Let’s look at some examples.

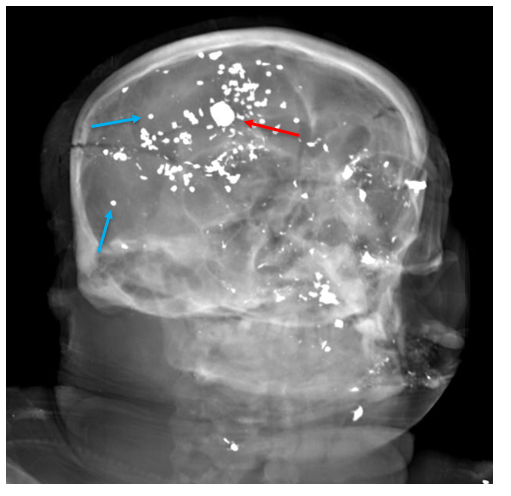

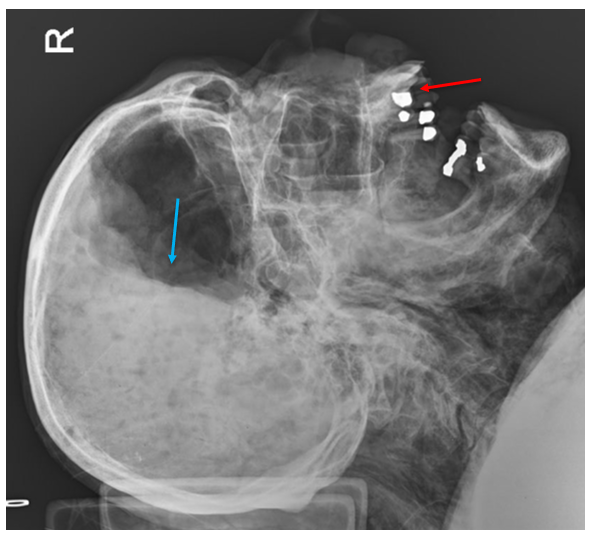

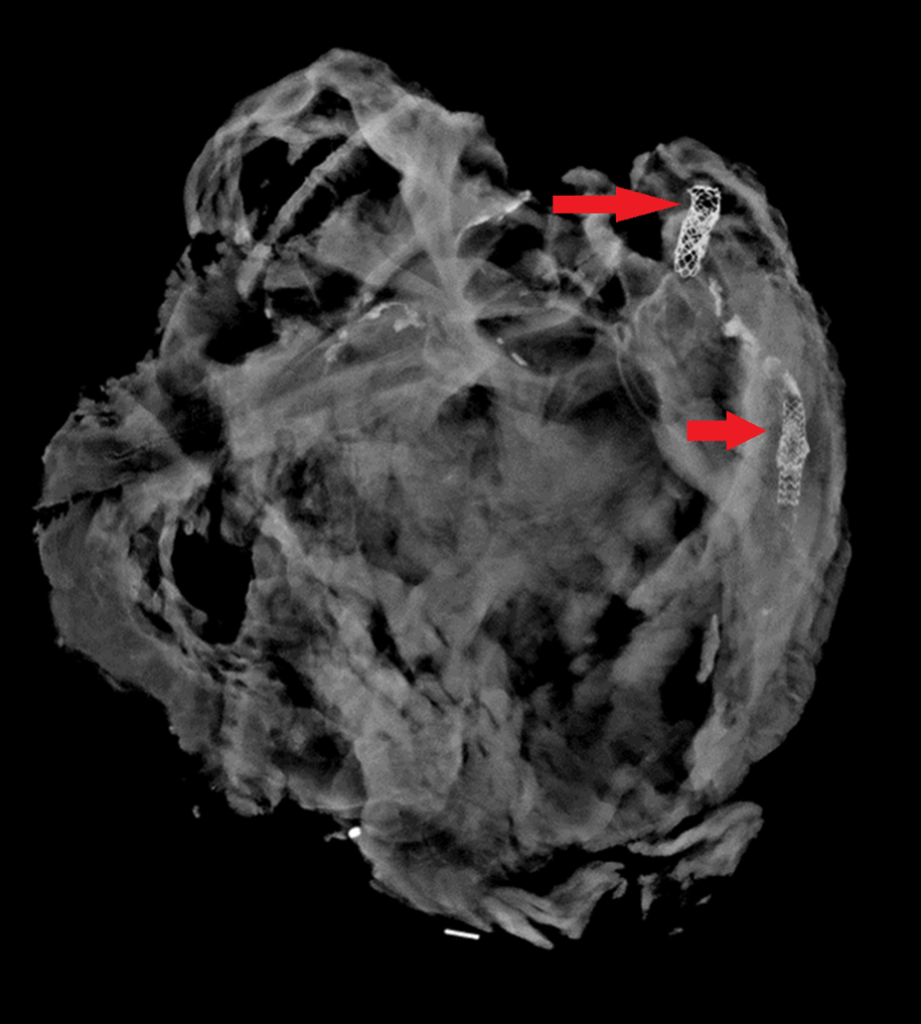

In the first pathway, consider an autopsy of a person with a single gunshot wound to the head. In a readily accessible region like the temple or beneath the chin, this wound could easily be self-inflicted. While this would be a “typical” location for a suicidal injury, such a wound could also be inflicted by another person. There are indicators we look for at autopsy which favor one scenario over the other. For example, most suicidal gunshot wounds (broadly speaking, of course) are contact wounds or intra-oral. A self-inflicted gunshot wound to the back of the head would be unusual, but (contrary to popular conception), not impossible depending on the firearm used. However, the same type of pattern could be elicited with another person holding a firearm to that individual’s head. We may examine the length of the firearm to determine if it’s possible for the decedent to have pulled the trigger themselves (keeping in mind that other items like a cane, coat hanger, or even the decedent’s toe, may have been used to depress the trigger). Similar questions can arise in autopsies of people who have fallen from height. There is no way an autopsy can tell with certainty whether an individual was pushed, fell accidentally, or left the edge of an elevated structure intentionally. The cause of death in both situations is undisputed – a gunshot wound in the first, and blunt force injuries in the second. This is why contextual information, like scene photographs and investigative records, is indispensable for forensic pathologists. Without context, we have no way to discern homicides, suicides, and accidents. Occasionally even with context, there can be competing narratives (one witness claims a gunshot wound was self-inflicted, while another claims it was inflicted by the first) or suspicious circumstances to cast doubt. Without clear cut evidence to support one story, the manner of undetermined is appropriate.

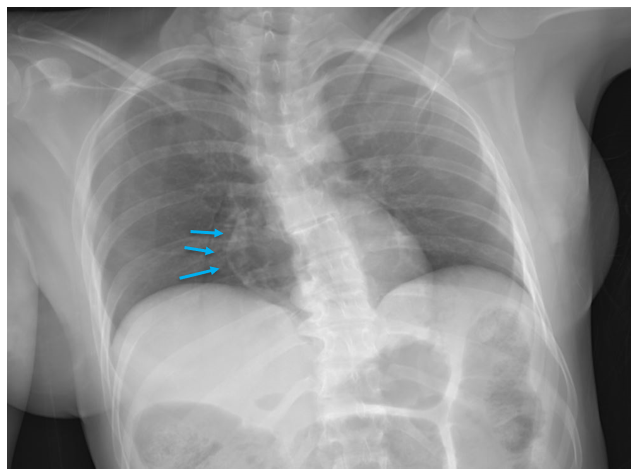

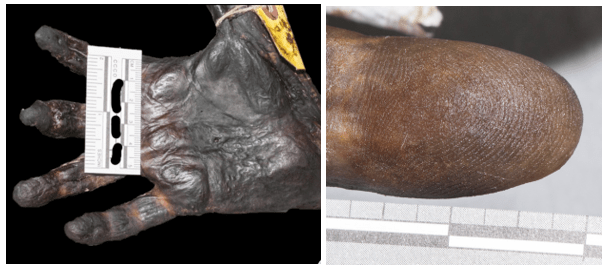

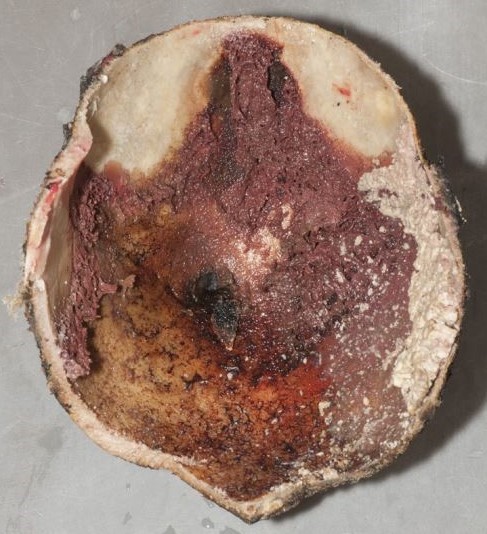

The second pathway by which we reach an undetermined manner is when extensive decomposition or other soft tissue loss (such as fire damage) interferes with our ability to determine a cause of death. Think of completely skeletal remains discovered in an abandoned building. Sometimes, indicators of potentially lethal injuries can still be identified – for example, a gunshot wound of the skull or knife marks on a rib. But, as the aphorism goes, “an absence of evidence isn’t necessarily evidence of absence” – a bullet or blade could be lethal while only striking soft tissue (especially in regions like the abdomen or neck). If we cannot rule out non-natural causes of death, the best choice for manner is “undetermined.”

An undetermined manner of death can understandably frustrate family members or law enforcement. I always try to explain that manner determinations are, as one of my mentors says, “written on paper and not in stone.” We reserve the right to change the ruling in the future if additional evidence comes to light. As forensics pathologists our primary responsibility is to speak honestly and truthfully, and sometimes that means admitting the limitations of our science.

-Alison Krywanczyk, MD, FASCP, is currently a Deputy Medical Examiner at the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office.