Case History

A 60 year old male from Louisiana presents to his family doctor with a chief complaint of longstanding skin lesions for approximately the last two years. On physical exam, there are several sharply defined reddish-brown plaques on his upper back and extremities. He reports sensory loss involving his chest, back and upper extremities. The lesions have not responded to conventional topical anti-fungal treatments. Punch biopsies along the margin of the most active lesion were obtained and sent to the Microbiology laboratory for bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures and to the Pathology Department for histologic diagnosis.

Tissue sections

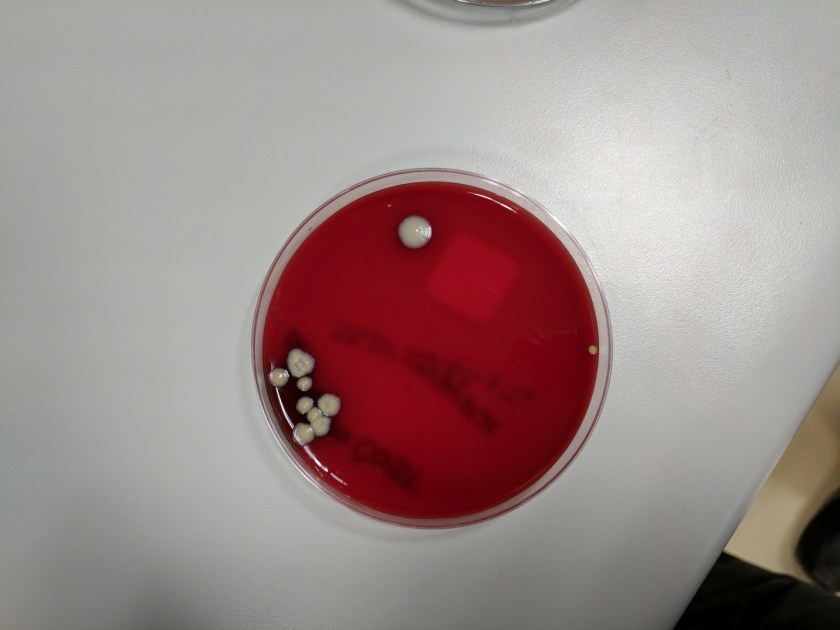

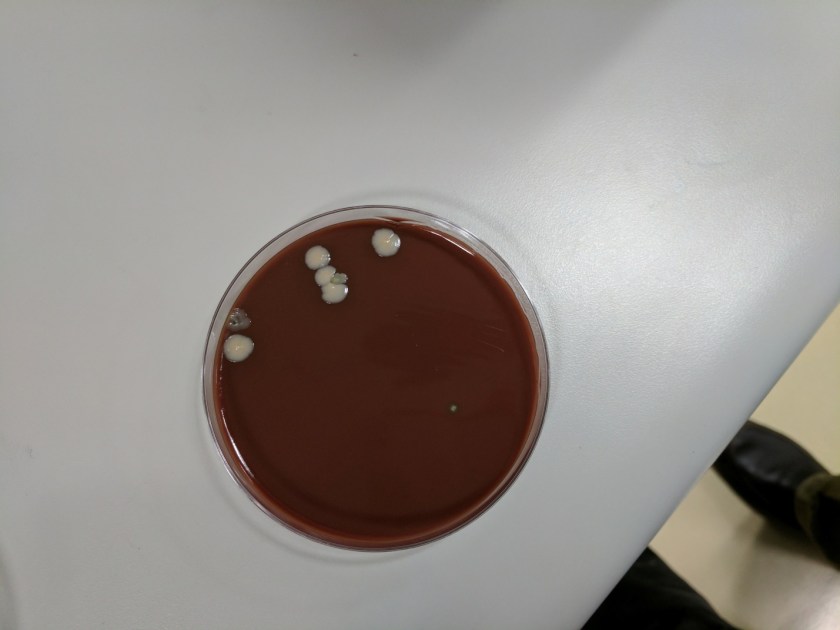

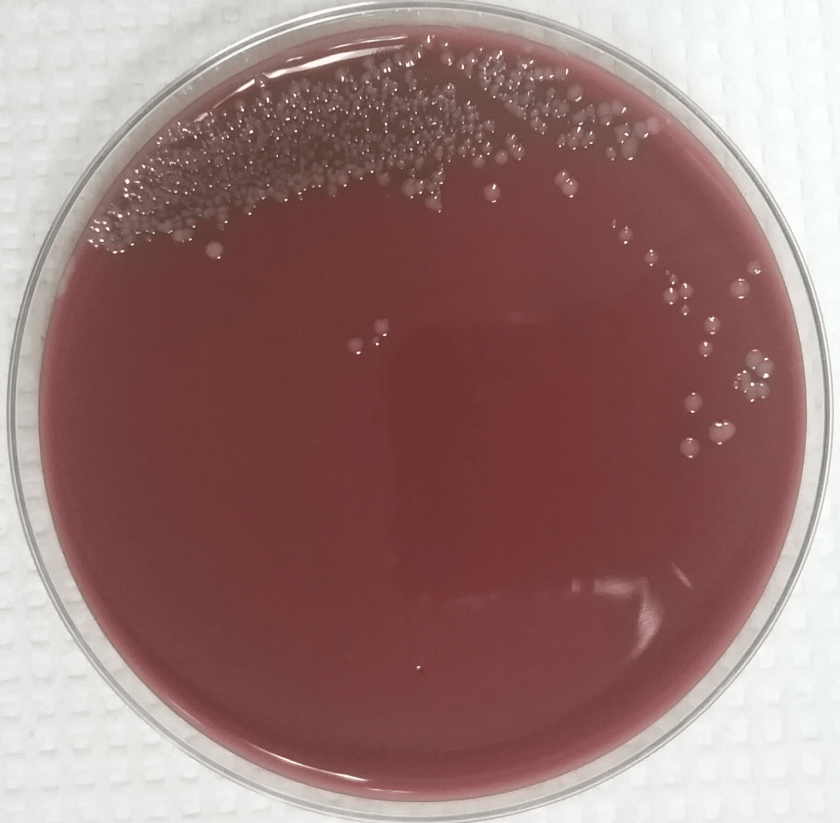

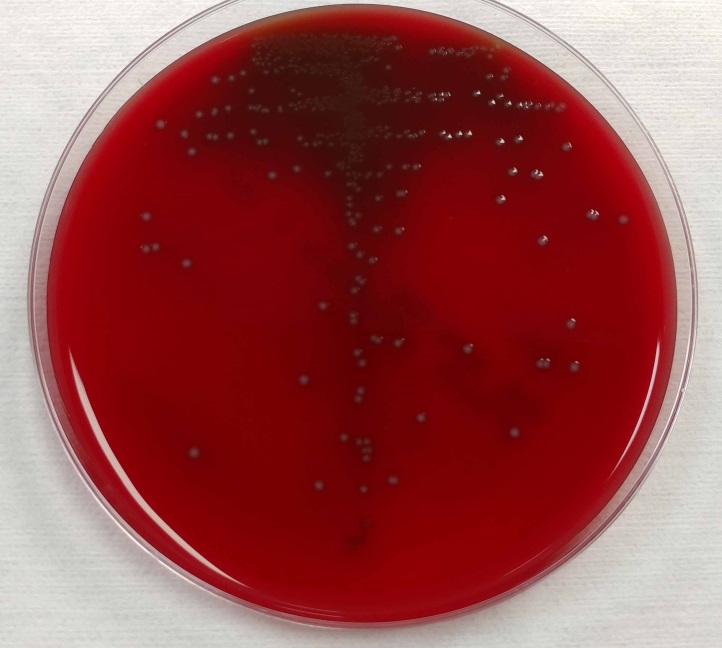

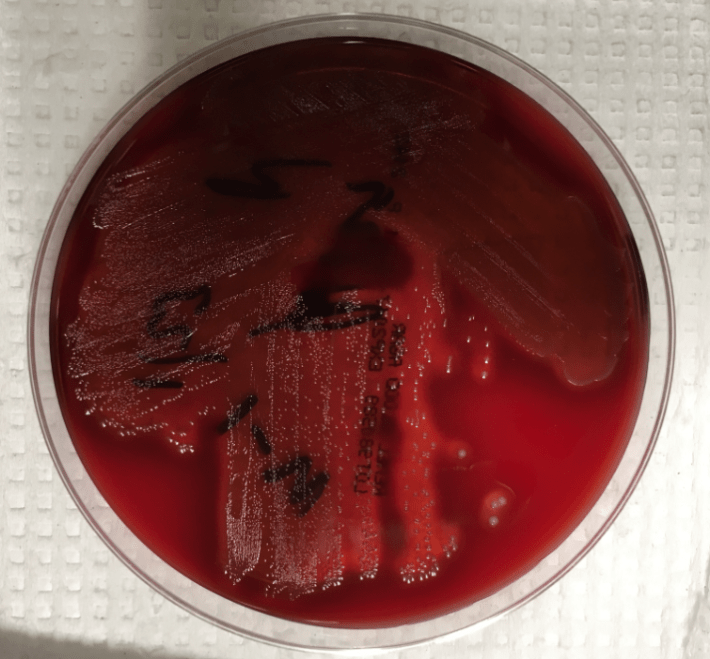

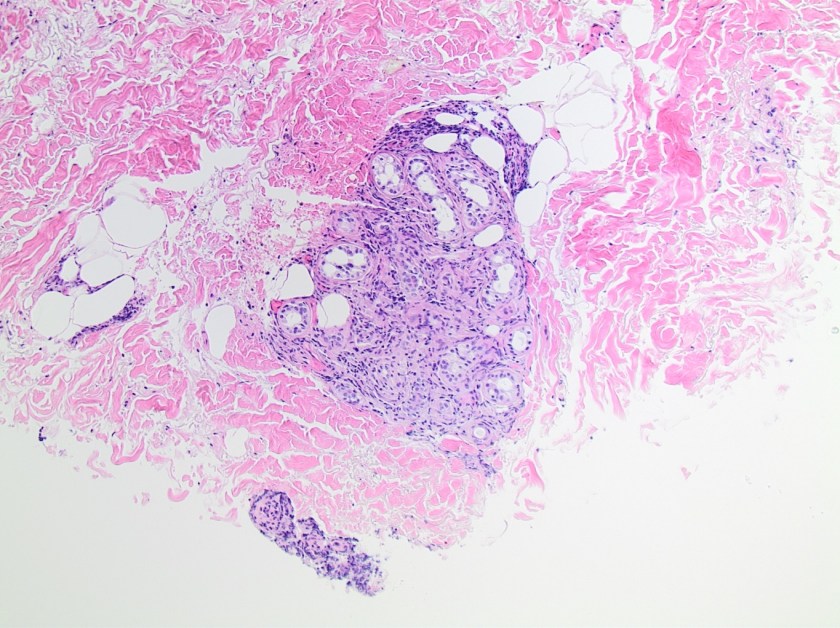

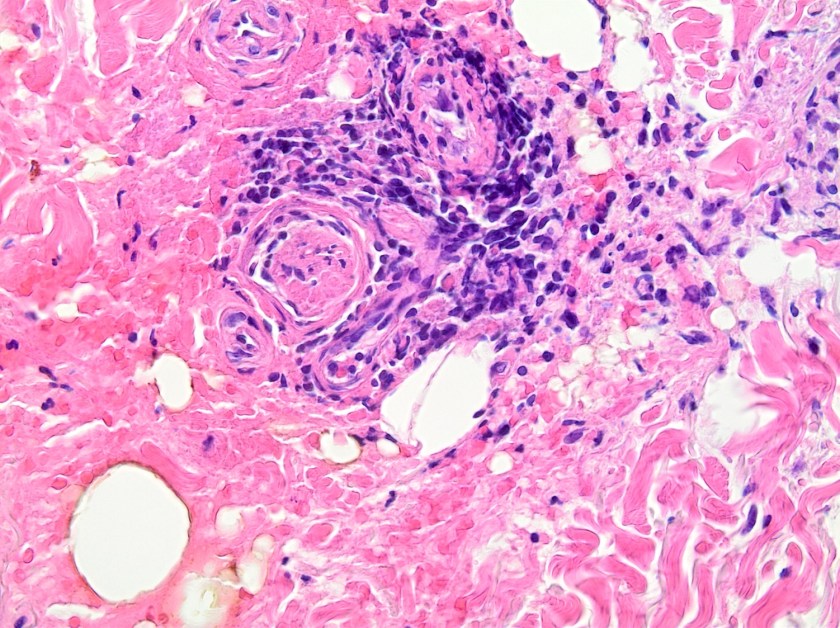

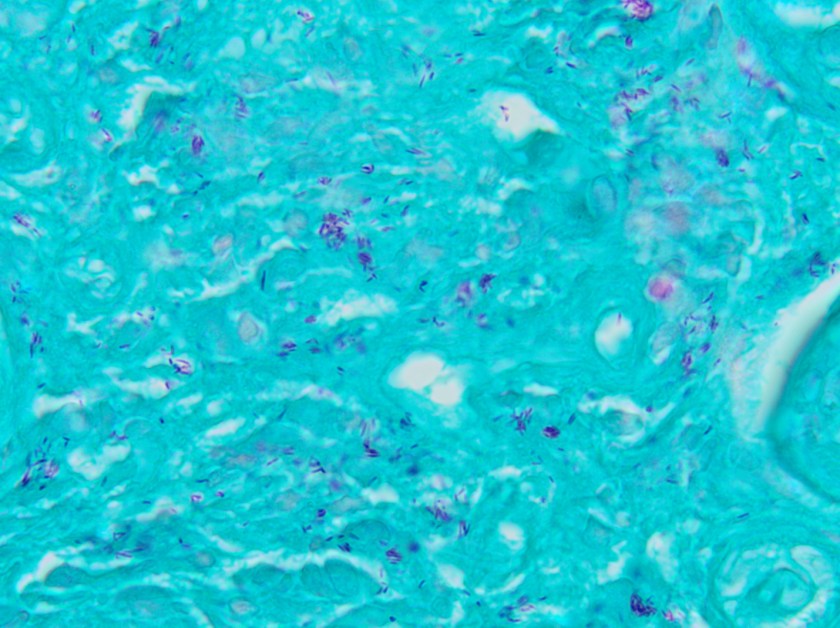

On histologic examination of the skin biopsy, nodular, superficial and deep granulomatous inflammation was noted surrounding eccrine glands and engulfing nerves (Images 1-3). Fite staining illustrated numerous acid fast bacilli (Image 4) and, given the geographic location of the patient and clinical symptoms, was felt to be highly suggestive of Mycobacterium leprae. The case was sent for confirmatory testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All cultures collected were negative.

Discussion

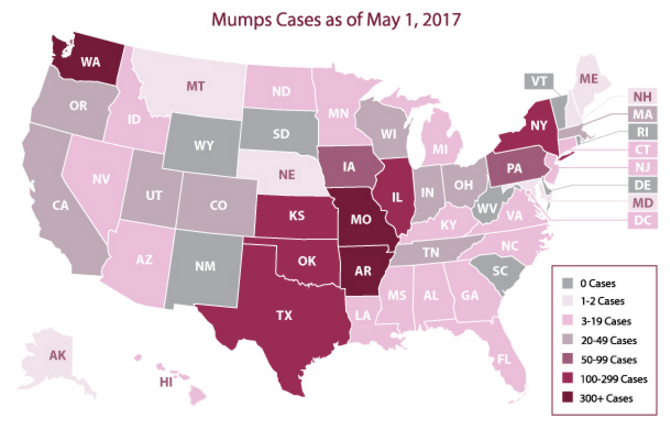

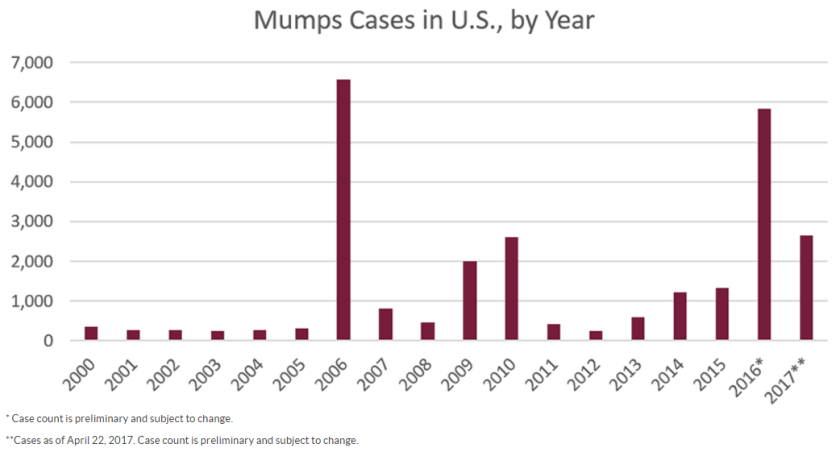

Mycobacterium leprae is a chronic, granulomatous disease which presents as anesthetic skin lesions and peripheral neuropathy with nerve thickening. While rare in the United States (US) today, historically it was one of most prominent pathogens in Mycobacterium genus apart from M. tuberculosis. In the past, leprosy (also known as Hansen’s disease) was prevalent throughout Europe, but due to systematic control programs aimed at underserved and rural locations, the number of cases drastically decreased and countries with the majority of recent cases include India, Brazil and Indonesia. According to National Hansen’s Disease Registry, a total of 178 cases were reported in the US in 2015. Of these, 72% (129) of cases were reported in Arkansas, California, Florida, Hawaii, Louisiana, New York and Texas. Transmission to those who are in prolonged and close contact with an infected person is thought to occur via shedding from the nose. While humans are the only known reservoir of leprosy, infections with organisms indistinguishable from M. leprae have been detected among wild armadillos in parts of the southern US.

The diagnosis of M. leprae is largely a clinical one as the organism is not able to be grown on artificial media, but histology and confirmatory PCR are useful adjuncts. Skin biopsies should be full thickness and include the deep dermis. Ideally, the most active edge of the most active lesion should be biopsied. There is a spectrum of M. leprae which ranges from few lesions and a paucity of bacilli (tuberculoid leprosy) to widespread skin involvement with numerous bacilli (lepromatous leprosy). Histologically, there are granulomatous aggregates of epithelioid cells, multinucleate giant cells and lymphocytes and inflammation often engulfs sweat glands and nerves. Small lesions that have poorly defined borders and are found on the elbows, knees or ears are where bacilli tend to be located. A Fite stain is useful to highlight the acid fast bacilli located in the macrophages within the inflammatory nodules. M. leprae PCR can also be performed on blood, urine, nasal cavity specimens and skin biopsies as a sensitive diagnostic technique. PCR can also be used to detect certain genes that confer resistance to common treatment drugs such as rifampin, ofloxacin and dapsone.

As with other mycobacterial diseases, the treatment for M. leprae infections consists of a long term multidrug regimen. The six most commonly used medications include rifampin, dapsone, clofazimine, minocycline, ofloxacin, and clarithromycin.

-Katie Tumminello, MD, is a fourth year Anatomic and Clinical Pathology resident at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

-Lisa Stempak, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pathology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. She is certified by the American Board of Pathology in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology as well as Medical Microbiology. She is the director of the Microbiology and Serology Laboratories. Her interests include infectious disease histology, process and quality improvement and resident education.