We’ve previously addressed the basics of gunshot wounds (see https://labmedicineblog.com/2023/09/22/the-ins-and-outs-of-gunshot-wounds/) but forensic pathologists need to be familiar with injuries inflicted by a variety of firearms. If you grew up in a rural area (like me) you are probably familiar with shotguns as a typical hunting tool. However, shotguns also have several unique characteristics which are crucial for forensic pathologists to understand.

First, the barrel of a shotgun is most often a “smooth bore” as opposed to the longitudinal spiraling lands and grooves (or “rifling”) found in the barrels of rifles and handguns. This means traditional ballistic “matching” (testing to see if a bullet was fired from a particular weapon) is impossible.

Secondly, shotgun ammunition is constructed differently. Broadly speaking there are three types of shotgun ammunition – birdshot, buckshot, and slugs (from smallest to largest in individual size).

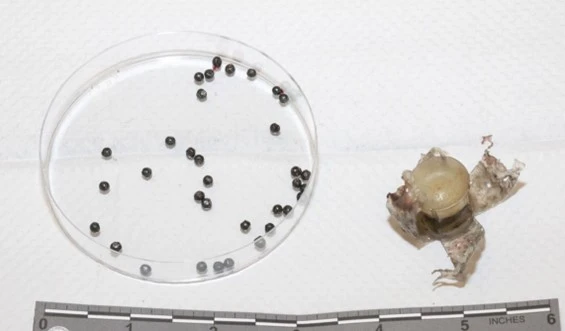

A single shotgun projectile is composed of the ‘shell’, an outer casing of plastic with a metal base. The shell contains primer and gunpowder, “wadding” (fiber or cardboard material), and a plastic “sleeve” which holds the projectile(s) (or “shot”). The individual characteristics can vary depending on the “gauge” (caliber) used, but a single shell will typically contain hundreds of birdshot pellets, tens of buckshot pellets, or one slug. The sleeve initially holds these individual pellets together – but upon leaving the barrel, the plastic flays outward, and the pellets or slug are released. For birdshot and buckshot, this means the individual pellets begin to spread apart and lose speed.

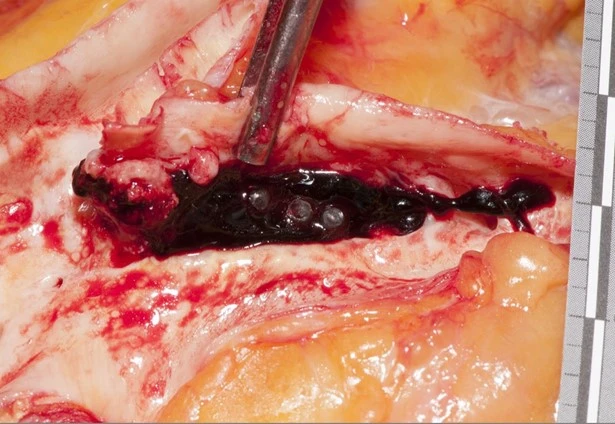

This spread of pellets explains why shotguns are a popular choice for hunting birds – a small, constantly moving target. It also helps us determine the range of fire from the shape of the entrance wound. At a close or contact range, there is minimal opportunity for the pellets to spread, resulting in a single circular wound. As the distance from the target increases to several feet, the wound edges become scalloped and individual pellet wounds are observed around the main entrance wound. At a distant range (approximately ten feet), there are only individual pellets wounds. Importantly, these wound characteristics can only be assessed on the skin surface – not on radiographs, which will only show the pellets in their final location within the body.

The other components of the shell can add to the wound characteristics. At contact range, the plastic sleeve (and even the shell) will enter the body but will likely not be visible by radiograph – these still need to be recovered as evidence. At medium distances, the sleeve and/or shell may strike the skin surface and impart a distinct patterned abrasion, without penetrating the skin.

Fortunately, shotgun wounds are a less common part of day-to-day practice – yet it is still important to be prepared with a basic understanding of how these weapons function and the diverse types of ammunition available.

References

DiMaio, Vincent J. Gunshot Wounds. 3rd ed., CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.

Dolinak, et al. Forensic Pathology: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Academic Press, 2005.

-Alison Krywanczyk, MD, FASCP, is currently a Deputy Medical Examiner at the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office.