Tag: transfusion medicine

New Technology for Transfusion Medicine

Late last year, the FDA approved Cerus’s INTERCEPT blood system for platelets and plasma. This system reduces the risk of transmitting blood-borne pathogens through platelets and plasma. INTERCEPT accomplishes this by inserting molecules into the DNA of pathogens that makes them incapable of replicating. While the pathogen still exists, it can’t replicate, and therefore can’t cause disease in the recipient. This is useful for well-known agents such as HIV or hepatitis as well as emerging diseases such as Chikungunya. Since it targets DNA, it would also neutralize undiscovered pathogens.

One potential downside of using this system is potentially increasing the cost of blood products for hospitals. Also, there is a bit of risk involved with being the so-called “first kid on the block” when using any new technology. While the FDA approval process is rigorous, unforeseen complications can arise with widespread use. Since the FDA approval, several blood centers—Delmarva, SunCoast, and Bonfils—have signed agreements to use this this system to ensure the functional sterility of their blood products. It will be interesting to see how widely this new technology is adopted and if blood products are made safer than with current methodologies.

If you’d like to read papers about this technology, you can find them here.

Reconsidering Mass Transfusion Protocols

In a new article exclusive to the Lab Medicine website, Gregory et al discuss mass transfusion protocols and argue against the 1:1:1 (1 unit each of platelets, plasma, and packed red blood cells) dogma. You can follow this link to read the paper.

What do you think? Is it time to reevaluate mass transfusion protocols?

Platelet-Rich Plasma: My View from the Transfusion Service

Platelets play a significant role in primary hemostasis, however they also serve as a reservoir of a number of important growth factors, including but not limited to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Thus, autologous platelets applied topically or injected into areas of recent surgical reconstruction or to wounds are thought to stimulate angiogenesis and aid in tissue repair/regeneration. Several instruments are available to harvest platelets, (re-suspended in plasma a.k.a. platelet-rich plasma, PRP), and this provides a vehicle for delivery as a topical or injectable product.

There is no doubt that basic science and in vitro studies substantiate the release of platelet-derived growth factors and their potential role in healing, however robust trials and in vivo studies are lacking and often show conflicting results. The lack of strong clinical evidence is due to the marked heterogeneity of PRP preparations, platelet counts, and growth factor yields or activity. Differences in the site of use, type of injury and tissue, and patient comorbidities likewise contribute to the broad range of study results. Dosing regimens for optimal use are also unknown. There are no evidence-based studies of head-to-head comparisons of these products or their relative efficacies on patient outcomes. Current literature maintains that there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of PRP in clinical practice. In spite of this, there continues to be extensive utilization of this product.

And I purposefully highlight the word product.

In my view, when allowing the use of instruments to acquire PRP, this represents manufacture of a blood product and constitutes a transfusion activity for which the Transfusion Service and specifically, the Transfusion Service Medical Director are ultimately responsible. All relevant transfusion activities fall under the auspice of the Transfusion Service and applicable standards would demand oversight of policies, processes and procedures. The AABB Standards for Blood Banks and Transfusion Services(1) clearly identify elements to be included such as equipment, suppliers, informed consent, document and record control, along with relevant quality and patient safety activities.

There are limited standards applicable to PRP specifically, such as storage temperature, expiration and conditions of use listed in the AABB Standards for Perioperative Autologous Blood Collection and Administration.(2) To this end, the International Cellular Medical Society(3), in 2011, noted a serious lack of guidelines surrounding the use of PRP and submitted a draft document which outlined elements for training, indications/contra-indications, informed consent processes, preparation, injection/application, safety issues and patient follow-up. A 2014 Cochrane Review called for standardization of PRP methods.(4)

Overall, I would venture to say that few hospital Transfusion Services are aware of the scope of use of PRP within their facility(ies). Regardless of one’s opinion of the current literature, I would urge all of us involved in transfusion practice to be informed of the use of PRP and to be vigilant in oversight of this activity. It is not merely a regulatory and accreditation issue, but our duty as laboratory physicians and clinical scientists to provide quality, safe and effective transfusion therapies to all patients. Often this requires educating our clinical colleagues and enabling them to understand our role in this critical process.

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READING:

- AABB Standards for Blood Banks and Transfusion Services, 29th edition, 2014

- AABB Standards for Perioperative Autologous Blood Collection and Administration, 5th edition, 2013

- cellmedicinesociety.org

- Morae VY et al. Platelet-rich therapies for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. The Cochrane Library 2014

- Griffin XL et al. Platelet-rich therapies for long bone healing in adults. The Cochrane Library 2012

- Leitner GC et al. Platelet content and growth factor release in platelet-rich plasma: A comparison of four different systems. Vox Sang 2006; 91: 135-138

- Everts PA et al. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: A review. J Extra Corpor Technol 2006; 38: 174-187

-Dr. Burns was a private practice pathologist, and Medical Director for the Jewish Hospital Healthcare System in Louisville, KY. for 20 years. She has practiced both surgical and clinical pathology and has been an Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Louisville. She is currently available for consulting in Patient Blood Management and Transfusion Medicine. You can reach her at cburnspbm@gmail.com.

Issues for Blood Management in Hematology/Oncology

Hematology/Oncology patients comprise a unique subpopulation for whom transfusion therapy is often necessary in both the acute care setting as well as for long-term support. Red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets are the most common components transfused particularly in patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy, intensive radiation therapy and human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Restrictive transfusion practice has become the “new world order” particularly for general medical and surgical patients. Those with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors have not frequently been a large part of many of the randomized controlled trials that speak to this approach. Literature is available, however, that provides evidence that judicious use of blood components via restrictive transfusion and single unit transfusions for inpatients and outpatients can be clinically effective, safe, and will decrease the potential for transfusion-associated adverse events.

Feasibility studies of restrictive RBC transfusion in the Hematology/Oncology population have been reported. These studies provide compelling evidence that lower transfusion triggers, targets and single unit use are not associated with increased bleeding episodes and will reduce overall transfusion exposure.¹ ² ³ The American Society of Hematology (ASH), as part of their Choosing Wisely Campaign, advises against liberal transfusion of RBCs with hemoglobin (Hgb) targets of 7- 8 g/dL, along with implementation of single-unit transfusions when possible.4

Recent RCTs and consensus from the AABB point to similar restrictive practice for platelet transfusion with a trigger of 10,000/µL for prophylactic transfusion in most patients.⁵ Subgroups of patients, such as those with autologous HSCTs, may not require prophylactic transfusion at this level, but can be effectively transfused using a therapeutic-only strategy.⁶ The use of lower doses of platelets has been shown to be safe and effective.⁷ Similar strategies may also be applicable for outpatients.⁸

Pursuant to those patients receiving radiation therapy, historically, there have been reports in the literature that found loco-regional control to be improved in patients whose Hgb is maintained at a higher level, typically > 10 g/dL. Many, if not most of these studies had significant confounding and have not adjusted for comorbidities. A publication in 2012, however, concluded “…that hypoxia is a well-established cause of radio-resistance, but modification of this cannot be achieved by correcting low Hgb levels by…transfusion and/or [ESAs[.”⁹ Similarly, a recent study covering over 30 years of experience with cervical cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy (the original target population from a historical perspective) adjusted for confounders and found no evidence that anemia represented an independent predictor of outcomes associated with diagnosis or treatment. ¹° Transfusion, in and of itself, has significant negative immunomodulatory effects via cell-to-cell interactions and cytokines. Thus, maintenance of Hgb levels for these patients should not be considered an absolute necessity.

Other interventions may prove successful for Hematology/Oncology patients as part of a Blood Management Program. Identification and treatment of concomitant iron deficiency anemia or other nutritional deficiencies can potentially decrease or eliminate the need for transfusion. Drugs that might increase the risk for bleeding or hemolysis should be eliminated if possible as these cause or potentiate anemia. Use of new targeted drugs such as lenalidomide in patients with 5q deletion-associated MDS may prevent the need for long-term transfusion dependence. The use of antifibrinolytics in patients who have become refractory to platelet transfusions can enable platelet function even at low levels and prevent the unnecessary use of limited platelet resources.

Outpatient transfusion in the Hematology/Oncology arena comes with some unique circumstances. Many outpatients remain stable and will be capable of lower transfusion thresholds and longer intervals for both RBCs and platelets. Evidence-based restrictive transfusion can and should be a part of outpatient treatment strategy, just as with inpatients if the accessibility to post-transfusion care is adequate. No national guidelines are available for outpatient transfusion and each patient scenario must be considered on an individual basis, but certainly the absolute need for “standing” transfusions and obligatory 2-unit transfusions should be discouraged. Consider, as well, that patients often have their own view of the “need” for transfusion when symptoms and signs do not necessarily make it requisite. Discussion with our patients is essential to allow them to understand transfusion decisions.

The risks of transfusion are both immediate and delayed, particularly for those with chronic transfusion needs. Febrile non-hemolytic, allergic, hemolytic reactions, TRALI and TACO may occur as in other patient populations and should be recognized and treated as appropriate. Alloimmunization and transfusion-related iron overload are more common in the Hem/Onc arena given the potential for increased component exposure during the acute care setting and the high percentage of those that necessitate chronic transfusion support. The potential for transfusion-associated graft vs. host disease is also more worrisome given the degree of immunosuppression in these patients. Specialized products are often necessary including leukoreduced, antigen negative, irradiated or HLA-matched components. These specialized products may not be available on a STAT basis and add significantly to the overall transfusion cost. Careful consideration is warranted and inclusion of the Transfusion Service is key.

In the end, transfusion practice for Hematology/Oncology patients should include restrictive transfusion practices with assessment of the risks and benefits at the time of each potential transfusion episode. Each patient, whether inpatient or outpatient, should be evaluated based on their current state of stability, clinical course and availability and access to care. Nutritional assessments and subsequent interventions along with pharmaceutical agents may provide additional ways by which transfusion exposure can be decreased. Special products are often necessary and needs should be discussed with the Transfusion Service. Limiting transfusion ultimately avoids unpleasant, potentially severe acute and delayed adverse events as well as preserving resources within our communities.

References:

- Jansen et al. Transfus Med 2004; 14: 33

- Berger et al. Haematologica 2012; 97: 116

- Webert et al. Transfus 2008; 48: 81

- choosingwisely.com

- Kaufman et al. Ann Intern Med 2014; doi: 10.7326/M14-1589

- Stanworth et al. Transfus 2014; 54: 2385

- Slichter et al. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 600

- Sagmeister et al. Blood 1999; 93: 3124

- Hoff Acta Oncologica 2012; doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.653438

- Bishop et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.023

-Dr. Burns was a private practice pathologist, and Medical Director for the Jewish Hospital Healthcare System in Louisville, KY. for 20 years. She has practiced both surgical and clinical pathology and has been an Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Louisville. She is currently available for consulting in Patient Blood Management and Transfusion Medicine. You can reach her at cburnspbm@gmail.com.

New Study Suggests No Difference in Mortality Rate in Two Different Transfusion Ratios

From the study published in the Journal of the American Medicine Association: “Among patients with severe trauma and major bleeding, early administration of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 ratio compared with a 1:1:2 ratio did not result in significant differences in mortality at 24 hours or at 30 days. However, more patients in the 1:1:1 group achieved hemostasis and fewer experienced death due to exsanguination by 24 hours.”

You can read the NIH press release here.

You can read the abstract for the study here.

The Bombay Phenotype

ABO and H are the most important of the currently characterized blood group systems, since incompatibility between transfused red cells and recipient plasma leads to potentially devastating consequences. Those learning about this system spend lots of time memorizing biochemical details that can be overwhelming. In addition, exam-writers seem to enjoy asking questions about unusual entities in these systems that most blood bankers will never see in real life. Two very rare situations with altered red blood cell appearances (“phenotypes”), known as “Acquired B” and “Bombay,” are among those most frequently discussed on examinations. In a previous post, I discussed the Acquired B Phenotype (see my web page for further details and a video presentation). Today, let’s proceed with details about the very famous Bombay Phenotype.

In the 1950’s, a small group of people were identified in an area in India surrounding the city of Bombay (now called “Mumbai”) that appeared to be blood group O at first glance. As you should know from a basic understanding of the ABO system, group O individuals have antibodies against both A and B antigens, and as a result, can only receive red blood cells from donors who are also group O. The patients reported by Bhende et al (Lancet 1952;1:903-4), however, carried an extra antibody in their plasma that made them INCOMPATIBLE with others that were truly blood group O. These individuals (and others described since) lack a precursor antigen known as “H” both on their RBCs as well as in their secretions and plasma.

In brief, ABO antigens on red blood cells are made in a sequential manner. First, long sugar chains attached to either lipids or proteins (glycolipids or glycoproteins, respectively) on the surface of the RBC must be modified through the work of an enzyme encoded by the H (FUT1) gene (chromosome 19) to display H antigen activity. Only then can the chain be further modified by the action of a second enzyme that adds a single sugar to change that H antigen into either an A or a B antigen. The alleles inherited at the ABO gene site on chromosome 9 (A, B, and/or O) determine which ABO antigens will be expressed on the red cell surface, but again, such a change ONLY happens if the precursor antigen (H) is made first.

ABO antigens are unusual in that they are not only attached to RBCs, but are also present in free-floating forms throughout the body. The same manufacturing principle (first make H, then make A or B) applies to the formation of soluble ABO antigens found in virtually all bodily fluids, including plasma and saliva (and other secretions). The enzyme that is responsible for H antigen formation in these fluids is different than the one described above; it is encoded by the Se (FUT2) gene (also on chromosome 19).

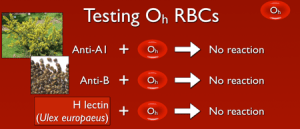

If a person lacks both active forms of both the H (FUT1) and Se (FUT2) alleles (described as having the genotype hh, sese), they are incapable of making H antigen either in secretions and plasma AND on the surface of the RBC (they are described as “H-deficient non-secretors”, and commonly with the shorthand Oh). The genetic mechanism of these changes is well described in the original cohort in India (a particular single nucleotide polymorphism in FUT1 accompanied by a total deletion of FUT2), and multiple additional mutations have been identified that could lead to someone lacking active forms of both alleles.

So, with that out of the way, what does this mean? Well, if a person lacks the ability to make H antigen in both RBC-based and free precursor chains, they will appear to be blood group O, just like someone who inherits two O alleles at the ABO site. However, unlike group O RBCs, which carry more H antigen than any other ABO group, H-deficient non-secretor RBCs have NO H antigen (this can be demonstrated easily in blood banks by showing no reaction when the RBCs are mixed with the H lectin Ulex europaeus). In keeping with the way other ABO system antibodies are formed, Bombay individuals make anti-A, anti-B, and anti-A,B, exactly like others that are group O. However, they also make a strong and very dangerous anti-H. The antibody is primarily IgM, but like most ABO-related antibodies, it reacts strongly at body temperatures, and generally is considered highly capable of giving rise to dangerous hemolytic transfusion reactions. As a result, Bombay patients can really receive blood only from others who completely lack the H antigen (which functionally means they should either get their own blood that has been stored for their future use or blood from another H-deficient non-secretor).

There are variants of Bombay, most notably the “Para-Bombay” phenotype in which the patient is H-deficient on RBCs, but IS capable of making ABO antibodies in secretions and plasma (these patients are H-deficient secretors). The key fact that must be evaluated in all of the Bombay-related phenotypes is whether or not an anti-H has been formed that is capable of reacting at body temperature. If so, Bombay variants must also receive only H-deficient red blood cells.

As mentioned, most workers will never see a patient with the Bombay Phenotype. This entity is seen mostly in examination world, but it is nonetheless very important for transfusion service personnel to be aware of this rare phenotype and prepared to take steps to diagnose it. I have seen reports of Bombay cases misdiagnosed as non-ABO high-frequency alloantibodies, and am aware of a case where the diagnosis became apparent when a child was born with an ABO type that seemed impossible based on the ABO types of the parents.

-Joe Chaffin, MD, is the new Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for LifeStream, a Southern California blood center headquartered in San Bernardino, CA. He has a long history of innovative educational efforts and is most widely known as the founder and chief author of “The Blood Bank Guy” website (www.bbguy.org).

Acquired B Phenotype

Students learning about the ABO blood group system commonly get confused about two unique situations: The Acquired B phenotype and the Bombay phenotype.

These two entities are VERY different, but they are similar in this way: people are asked about both on exams all the time, but hardly anyone every actually SEES either one in real life! It is essential for students of blood banking to understand Acquired B clearly, as it remains a real possibility in everyday practice. I’ll cover Acquired B in this month’s blog, and next month I will discuss Bombay.

Routine ABO testing is performed in two distinct (but usually simultaneous) stages, known as “red cell grouping” (forward grouping or “front type”) and “serum grouping” (reverse grouping or “back type”). Here’s an example of how it works: If a person’s red blood cells (RBCs) react strongly with reagent anti-A but not anti-B, we would interpret their red cell grouping as blood group A. If there is no ABO discrepancy, that same person’s serum should have no reaction with reagent group A1 RBCs and strong reaction with reagent group B RBCs (demonstrating the expected presence of anti-B in the serum). Thus, the serum grouping interpretation would also be blood group A, and no ABO discrepancy would exist (see this illustrated in the figure below).

ABO discrepancies occur any time the interpretations of a person’s red cell and serum grouping do not agree. ABO discrepancy takes on many forms, and acquired B is a great, if not terribly common, example.

Students learning about the ABO blood group system commonly get confused about two unique situations: The Acquired B phenotype and the Bombay phenotype.

Usually, Acquired B occurs when the RBCs from a blood group A patient come in contact with bacterial enzymes known as “deacetylases.” These enzymes, commonly carried by bacteria that live in the colon, catalyze the removal of the acetyl group from the residue that gives the A antigen its specificity, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc). This modification leaves the A-specific sugar as galactosamine (N-acetylgalactosamine with the acetyl group removed = galactosamine). Recall that normally, the group B-specific sugar is galactose.

As a result of this modification, anti-B in both human group A serum and especially certain monoclonal reagents will weakly agglutinate the group A RBCs carrying the acquired B antigen. This means that the patient’s RBCs may have a weakly positive reaction with anti-B in serum grouping tests instead of the expected negative (see image below). The serum grouping for these patients is no different from that expected for a group A individual (negative with group A reagent RBCs, strong positive with group B RBCs).

So, what does this actually mean? How do these patients actually get transfused? This is where the recognition of the entity in a transfusion service or reference laboratory is essential. Several simple strategies can be employed to prove that this patient is really NOT group AB. First, I always advise people to check the patient history! The rare cases of acquired B that are still seen will often be associated with colorectal malignancy, gastrointestinal obstruction, or gram-negative sepsis (where those bacteria can contact the RBCs). Second, adding the patient’s own serum to his RBCs (autoincubation) reveals no incompatibility. In other words, this patient’s own very strong anti-B does not recognize the acquired B antigen (which is really just a partially modified group A antigen) as being an actual group B antigen. We already know that this patient has anti-B in his serum from his serum grouping results (see above), but the patient’s own anti-B completely ignores the acquired B antigen on his RBCs (even though human anti-B from other people will react). Third, the technologist can use a different form of monoclonal anti-B in the patient’s red cell grouping test. Certain clones are known to react with acquired B, while others are not (normally specified in the package insert), and choosing a different clone (often easier in reference lab settings) will render the forward grouping consistent with that of a group A person. Also, incubating the Acquired B RBCs with acetic anhydride will lead to “re-acetylation” of the modified A antigen and loss of the B-like activity. Finally, acidifying the reaction mixture of the patient’s RBCs with human anti-B (non-self) can eliminate the incompatibility with that source of anti-B.

In the end, Acquired B is a serologic problem that is fairly easy to recognize, especially on examinations (I always tell my students that when they see a problem that starts with words like, “A 73 year old male with colon cancer…”, check the answer for Acquired B!). In real life, experienced blood bankers can diagnose and confirm Acquired B fairly easily in the rare times that it is seen. These patients can receive group A blood without a problem, and the ABO discrepancy will disappear as the infection or other situation causing causing contact with bacterial enzymes clears. Thanks for your time and attention. See you next month when I will discuss the Bombay Phenotype!

-Joe Chaffin, MD, is the new Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for LifeStream, a Southern California blood center headquartered in San Bernardino, CA. He has a long history of innovative educational efforts and is most widely known as the founder and chief author of “The Blood Bank Guy” website (www.bbguy.org).

Designer Blood

Recently scientists have discovered transcription pathways that turn pluripotent stem cells into red blood cells and white blood cells. (You can read the article here.) This could be the first step in making patient-specific blood products or a way to increase the nation’s blood supply without having to rely on volunteer donors. What do you think? Could this be the future of transfusion medicine?

What’s In a Name? Chikungunya and Dengue Viruses and the Blood Supply

“Incurable Virus Spreads in US!” In recent weeks, breathless and scary-sounding headlines like this have been seen in newspapers and web sites in the United States, describing an outbreak of emerging viruses with scary names like “Chikungunya” and “Dengue” seen in US travelers to the Caribbean, South America, and other tropical areas. While the news certainly sounds terrifying to the public, Transfusion Medicine professionals must evaluate donors carrying these “emerging” infections (defined as infections whose human incidence has increased in the last 20 years or so) as scientifically as possible to ensure the maximum safety of the blood supply. Let’s take a quick look at two of these infections and their implications for potential blood donors.

Chikungunya virus:

Chikungunya has quite possibly the greatest name in the history of viruses! Sadly, it is a fun-sounding name for a not-so-fun disease. This virus has been on our radar for a few years now, as it spread through Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of Europe. More recently, however, Chikungunya has become quite prominent in the Caribbean islands as well as Central and South America.

- Vector: Aedes species mosquitoes

- Spread: Human to human via mosquito vector

- Illness: High fever, severe joint pain that may last months, severe infections in already ill adults or neonates

- Treatment: No specific therapy or vaccine; just support symptoms

- Blood transmission: No cases reported, though theoretically possible

- Tests for donors: None approved by FDA

Though the CDC is monitoring numerous cases of Chikungunya in US citizens in multiple states exposed through mosquito bites during travel, we currently do not have great ways to track or test blood donors. Fortunately, at least 80% of people infected with this virus are symptomatic, and as a result, would be deferred from blood donation simply because they don’t feel well.

Dengue:

Dengue is another emerging infection that has been recently seen in US citizens, primarily those who travel to Asia and South America (in fact, according to the February 2014 update to the AABB Dengue virus fact sheet, Dengue is the most frequent cause of fever in US travelers returning from those areas; source: AABB web site). Worldwide, Dengue is a MASSIVE problem, affecting millions and killing over 22,000 people every year (source: CDC Dengue web site).

- Vector: Aedes species mosquitoes

- Spread: Human to human via mosquito vector

- Illness: High fever, rash, headache, severe lower back pain known as “break-bone fever”; Rare cases with hemorrhagic or shock

- Treatment: No specific therapy or vaccine; just support symptoms

- Blood transmission: Multiple well-proven transmissions from RBCs, platelets, and plasma

- Tests for donors: None approved by FDA

Dengue and Chikungunya infections can present in a very similar manner (high fever and joint pain). Dengue, however, is associated with much more severe consequences in a few patients, with diffuse hemorrhage and complete systemic collapse seen in a few patients.

Together, these viruses infect millions of people around the world every year. However, to date, neither has proven to be a large issue in US blood donors. In addition to the fact that potential blood donors infected by either virus will often be deferred because they do not feel well, many will also be prohibited from donating because they have traveled to an area where malaria is endemic (the malaria travel deferral covers much of the distribution area for both Dengue and Chikungunya).

It is clear to all Transfusion Medicine professionals that we are not completely “safe,” even though we have not yet seen an abundance of transfusion transmission of Dengue, and none whatsoever with Chikungunya. The presence of these non-treatable infections is simply another reminder that transfusion has risks aside from the ones that clinicians and patients think about most (HIV and hepatitis, for example). A big part of the job of a Transfusion Medicine professional is to help our clinician friends ensure that transfusions are only given when absolutely necessary.

Joe Chaffin, MD, is the new Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for LifeStream, a Southern California blood center headquartered in San Bernardino, CA. He has a long history of innovative educational efforts and is most widely known as the founder and chief author of “The Blood Bank Guy” website (www.bbguy.org).