Case Presentation

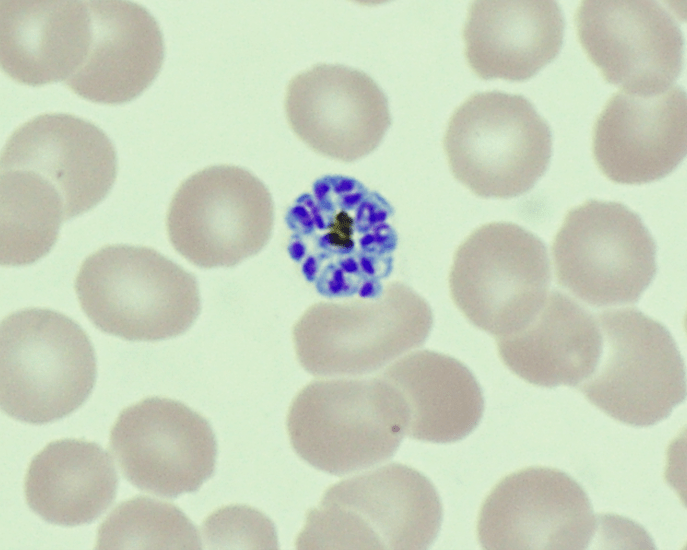

A 26 year old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with 1 week of malaise, high nightly fevers, abdominal pain, dark urine, and dysuria. He had no past medical history and was not taking any medications. He had been living in shelters since arriving in the US approximately 1 month ago after several months traveling through South and Central America from Venezuela. On review of systems, he also reported 3-4 days of constipation and a single episode of non-bilious, non-bloody vomit 2 days ago, accompanied by nausea. He denied mosquito bites, bloody or dark stools. On physical exam, patient appeared thin, mildly jaundiced, and had LUQ/LLQ moderate tenderness to palpation without guarding and splenomegaly. Given his travel history and presenting symptoms, the infectious disease service was consulted, and blood was drawn in the ED for further analysis. CBC and CMP were significant for normal WBC (10.21 x 103/mcL), normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 11.3 gm/dL, MCV 80.4 femtoliters), thrombocytopenia (48 x 103/mcL), hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 2.4 mg/dL, indirect bilirubin 1.7 mg/dL), and slightly elevated AST (46 units/L). Thin blood smear showed relatively enlarged erythrocytes infected with multiple ring forms and trophozoites with ameboid cytoplasm, consistent with Plasmodium vivax. Parasitemia was calculated to be 0.4%. The patient was diagnosed with uncomplicated malaria and started on artemether-lumefantrine for 3 days. He was found to a severe deficiency (41 units/1012 RBC) of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and therefore, at high risk of hemolysis if administered primaquine. Given his complex social situation, the patient decided to monitor himself for symptoms of relapse and defer starting primaquine for treatment of the liver stages of P. vivax. He was discharged to a local shelter with plans to follow-up closely with the outpatient infectious disease department, with strict precautions to return to the ED urgently for recurrent symptoms.

Discussion

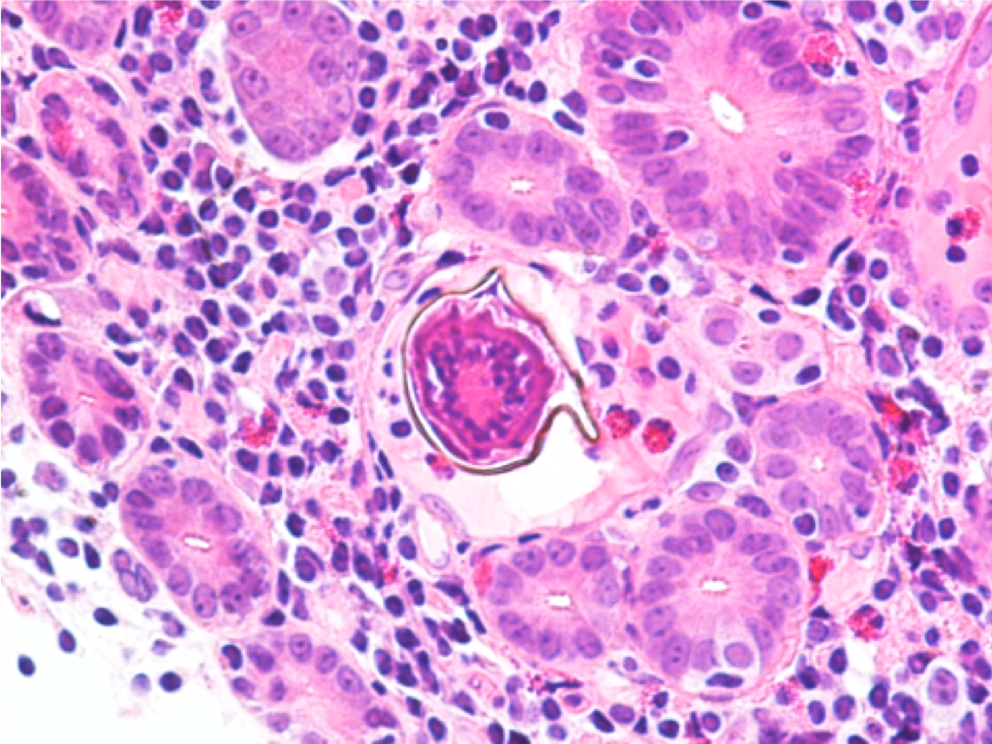

Malaria should be suspected when a patient presents with a febrile illness and a travel history within a malaria-endemic region. Diagnosis of P vivax can be made through microscopic examination of blood smears, immunochromatographic rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and nucleic acid detection through amplification techniques.1 Examination of a thick blood smear allows efficient screening for malaria parasites, while a thin blood smear allows for species identification since parasite morphology is more clearly visualized.2 Upon examination of thin blood smears, infections by P. vivax and P. ovale may appear indistinguishable as both species infect immature, enlarged erythrocytes (1.25-2x normal), can be visualized at any stage in peripheral blood (ring, trophozoite, schizont, and gametocyte) and because Schuffner’s dots are a common morphologic feature during most stages. Defining characteristics of P. vivax include the presence of a large, ameboid trophozoite cytoplasm, and fine Schuffner’s dots and schizonts with >12 merozoites. Of note, preparation with Giemsa stain over Wright stain is preferred for demonstration of Schuffner’s dots.2 Immunochromatographic RDTs detect parasite-specific antigens (e.g., Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase, Plasmodium specific aldolase) in a finger-prick blood sample. These tests are commercially available and relatively simple to perform and interpret, making them a useful tool for resource-limited regions.1 Nucleic acid amplification-based tools (e.g., PCR, loop-mediated isothermal amplification) are not routinely used for clinical management of malaria but do have diagnostic advantages over light microscopy and RDTs.3 PCRs are highly sensitive, can detect mixed infections even at low parasite densities, and are useful for epidemiological studies such as drug resistance identification.1

Malaria is a potentially fatal, but preventable and treatable, disease caused by infection of erythrocytes with protozoan parasites of the Plasmodium genus. Parasites are transmitted by the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitos. Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, P. knowlesi) infect humans. While each species of Plasmodium has unique characteristics, all species follow a similar life cycle. Erythrocyte lysis and release of merozoites cause release of pyrogens and production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-alpha, resulting in the symptomatic presentation of Plasmodium sp. infection, termed malaria. An important distinction between P. vivax and P. ovale and other Plasmodium species is that P. vivax/ovale may remain dormant in the liver (“hypnozoites”) and may resume intrahepatic replication, causing relapse of malaria weeks to years later.4 According to the WHO Malaria Report 2021, approximately half the world’s population lives in areas at risk of malaria infection. P. vivax is found predominately in Asia, Latin America, and some parts of Africa. It is the most common infective species in Latin America, accounting for an estimated 71.5% of cases in 2021.

The typical incubation time between transmission of parasites and onset of disease is approximately 14 days. P. vivax parasitesprimarily infect immature erythrocytes, representing 1-2% of the cell population. Synchronous replication and rupture of infected erythrocytes leads to the hallmark clinical presentation of cyclical severe fever and chills. Classically, P. vivax and P. ovale present with “tertian” malarial paroxysms, with fever and chills occurring every 48 hours. Patients may also complain of fatigue, malaise, headache, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, myalgias, dark urine, nausea, and vomiting. Additional clinical features and complications include anemia, jaundice, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly. Severe infection presents with hemodynamic instability, pulmonary edema, coagulopathy, organ failure, neurological dysfunction, and potentially death.4, 5

Chloroquine or artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) are both effective treatments against uncomplicated, non-falciparum malaria (P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, P. knowlesi).In a large systematic review, ACTs were found to be at least equivalent to chloroquine when treating the blood stage of P. vivax infection.6 ACTs are the drug of choice for non-falciparuminfections in countries where chloroquine resistance has developed, notably New Guinea and Indonesia.7To prevent relapse caused by hypnozoites of P. vivax/ovale, initial treatment is followed by administration of primaquine. Before treatment initiation with primaquine, quantitative testing for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency should be completed since this drug may induce hemolysis in those who are deficient. A modified dosing schedule under close medical supervision is used for those who are G6PD deficient. Treatment of severe malaria is with at least 24 hours of intramuscular or intravenous artesunate, with an option to transition to an ACT regimen once oral therapy can be tolerated.1

Malaria caused by P. falciparum is typically more severe than malaria caused by P. vivax since P. falciparum infects erythrocytes of all ages, causing extensive hemolysis and related complications.4, 5 P. vivax malaria may also cause severe malaria and also relapses, emphasizing the importance of radical cure of hypnozoites with primaquine.8 Expedient and appropriate treatment leads to resolution of fever and parasitemia within days, with successful treatment confirmed by undetectable parasitemia on blood smear. Recurrence of a febrile illness should prompt re-evaluation and may suggest recrudescence or relapse due to failed therapy, or reinfection.

References

1. World Health Organization. (2023). WHO guidelines for malaria, 14 March 2023. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/366432.

5. Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA. Chapter 9: The Malarias. In: Parasitic Diseases. 7th ed. Parasites Without Borders, Inc.; 2019:93-122.

4. Ryan KJ. Chapter 51: Apicomplexa and Microsporidia. In: Sherris & Ryan’s Medical Microbiology. 8th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://accessmedicine-mhmedical-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/content.aspx?bookid=3107§ionid=260929904

2. DPDx – Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern: Malaria. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated: October 6, 2020. Accessed: June 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/malaria/index.html

3. World Health Organization. Malaria Policy Advisory Group: Meeting Report of the Evidence Review Group on Malaria Diagnosis in Low Transmission Settings. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Headquarters, 2013. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/meeting-report-of-the-evidence-review-group-on-malaria-diagnosis-in-low-transmission-settings

6. Gogtay N, Kannan S, Thatte UM, Olliaro PL, Sinclair D. Artemisinin-based combination therapy for treating uncomplicated Plasmodium vivax malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(10):CD008492. Published 2013 Oct 25. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008492.pub3

7. Price RN, von Seidlein L, Valecha N, Nosten F, Baird JK, White NJ. Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(10):982-991. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2

8. Dini S, Douglas NM, Poespoprodjo JR, et al. The risk of morbidity and mortality following recurrent malaria in Papua, Indonesia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):28. Published 2020 Feb 20. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-1497-0

-Cleo Whiting is a fourth-year medical student at George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences. Her research interests include infectious disease, autoimmune disease, and dermatopathology.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.