Case History

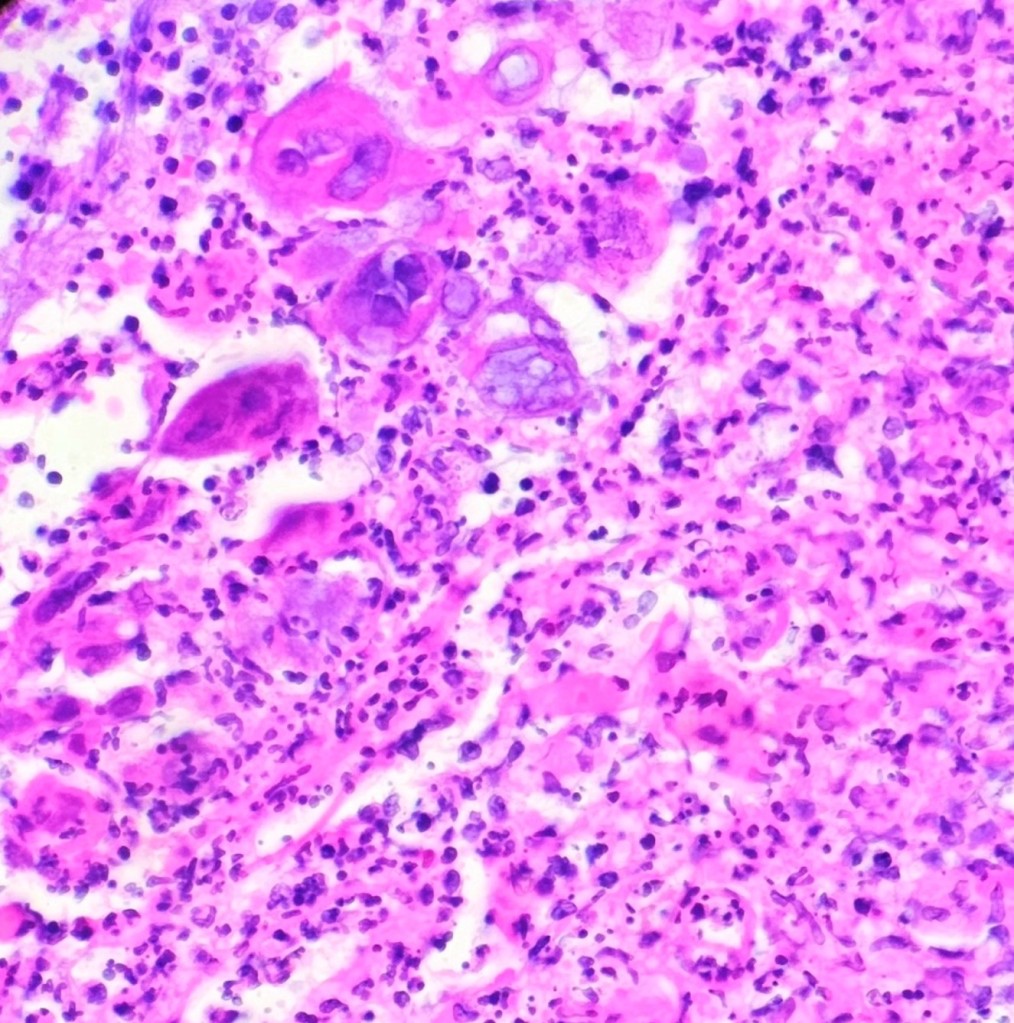

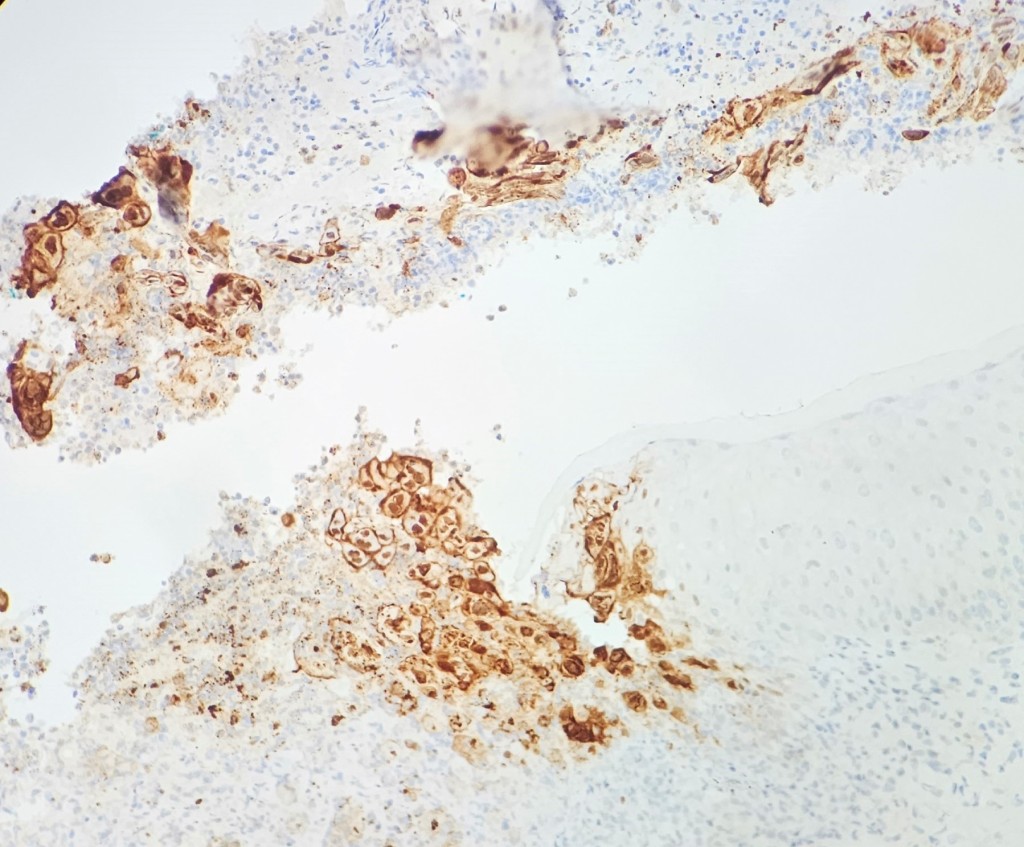

A 35 year old female patient with a past medical history of uncontrolled HIV, retinitis caused by cytomegalovirus and recurrent colitis presented to the Emergency Department with body pain, fever, severe neutropenia, and diarrhea. CT scan revealed worsening sigmoid/rectal wall thickening. Patient also presented with esophageal candidiasis. Blood workup revealed that the patient had sickle cell disease (HBSC), anemia (Hgb 5.6 gm/dl) that required multiple transfusions, and elevated white blood cell count (up to 17,000). The patient also had leukopenia (neutropenia and lymphopenia), which, in addition to the anemia without hemolysis or bone marrow compensation and CD4 count <50, led to strong suspicious of disseminated mycobacteria infection. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and AFB staining revealed loose granulomas and numerous acid-fast bacilli seen. Culture of the bone marrow grew out acid-fast bacilli further identified as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC).

Discussion

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is made up of several nontuberculosis mycobacterial (NTM) species that require genetic testing to be speciated.1 MAC is predominantly made of the slow-growers mycobacteria (SGM) such as M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. chimaera, and M. colombiense.2,3 Most species of nontuberculosis mycobacteria are found in environmental sources. The MAC organisms are found throughout the environment, particularly in the soil and water, mainly in the Southeast of the United States.1 Human diseases are most likely from exposure to environmental sources either through direct inhalation, implantation or indirect consumption or contamination food or water. MAC is considered the most commonly encountered group of slow growers.

The MAC cause pulmonary disease that is clinically similar to tuberculosis, mostly in immunocompromised patients with CD4 cell counts less than 200/μL, such as those with HIV/AIDS. They are the most frequent bacterial cause of illness in patients with HIV/AIDS and immunosuppression.1,4 MAC is also the most common nontuberculosis mycobacterial species responsible for cervical lymphadenitis in children. Additionally, hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like symptoms can occur which were initially thought to be an allergic reaction only, but current studies suggests infection and inflammation. Traditionally, MAC cause chronic respiratory disease, populations such as middle-aged male smokers and postmenopausal females with bronchiectasis (also known as Lady Windermere syndrome).

Diagnostic testing for pulmonary infection caused by MAC includes acid-fast bacillus (AFB) staining and culturing of the appropriate specimens. Respiratory specimens are the most commonly tested specimen type. If disseminated MAC (DMAC) infection is suspected, culture specimens should include blood and urine. Blood cultures are typically used to confirm the diagnosis of DMAC in an immunocompromised patient with clinical signs and symptoms 5. MAC can also be isolated from bodily fluids and other tissues, such as lymph nodes and bone marrow. If diarrhea is present, stool cultures can be collected. Skin lesions should be cultured if clinically warranted. To determine pulmonary involvement, imaging studies of the chest should be performed. Lymph node biopsy or complete lymph node excision is usually used to diagnose MAC lymphadenitis in children. Skin testing (MAC tuberculin test) has little value in establishing a diagnosis.6 Routine screening for MAC in respiratory or GI specimens is not recommended.

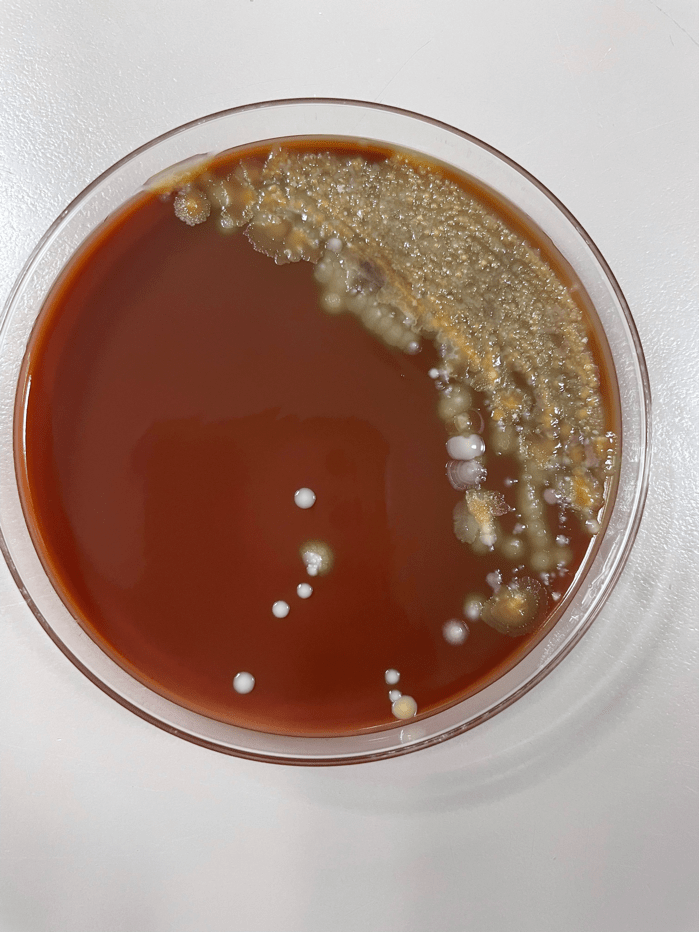

Organisms part of the MAC are not stained well by the dyes used in Gram stain, but instead are acid-fast positive. The ability of an organism to hold onto the carbol-fuchsin stain after being treated with a mixture of ethanol and hydrochloric acid is referred to as “acid-fast.” The high lipid content (around 60%) in mycobacteria’s cell wall makes them acid-fast. SGM require more than 7 days of incubation. Growth of M. avium species can be visualized in both LJ and 7H11 media 5. Colony morphology can be smooth or rough. Biochemical reactions to both niacin and nitrate reduction are negative. Upon growth, colonies can be identified using the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry 6. However, depending on the database and technology used, reports from the MALDI-TOF may report MAC as M. avium complex or into the individual subspecies. Molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction or whole genome sequencing, as well as high-performance liquid chromatography, are required for species identification. Direct detection of nucleic acid in clinical specimens by PCR methods have been reported, although most tests are laboratory-developed and FDA-approved. Molecular technologies typically target the 16S rRNA gene, the 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region or the heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) gene. Prior to PCR, the AccuProbe test was the first commercial molecular assay for identification of mycobacteria by targeting 16S RNA 7. In Japan, an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit was used to detect serum IgA antibodies to MAC-specific glycopeptidolipid core antigen. This could be useful for serodiagnosis of pulmonary infections caused by the MAC. This EIA kit’s sensitivity and specificity have been reported to be 54-92% and 72-99%, respectively 8. Other serologic tests are also being investigated.

While this may not aid in the direct detection of MAC infection, a complete blood count (CBC) in DMAC patients frequently shows anemia and, on rare occasions, pancytopenia due to bone marrow suppression caused by the infection, though either leukocytosis or leukopenia may be present. Hypogammaglobulinemia may be another possibility 9. Patients with DMAC typically have elevated transaminase and alkaline phosphatase levels on liver function tests. An HIV test should be performed if pulmonary or disseminated MAC infection is suspected.

MAC is extremely resistant to antituberculosis medications, and a combination of up to six medications is often needed for effective treatment. The preferred medications at the moment are ciprofloxacin, rifabutin, ethambutol, or azithromycin combined with one or more of these other medications 4. For patients with HIV, azithromycin is currently advised as a preventative measure. Of note, preventive treatment of MAC colonization in asymptomatic patients is also not advised. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommends performing antimicrobial susceptibility testing using broth microbroth dilution technique. Breakpoints for clarithromycin, amikacin, moxifloxacin, and linezolid are reported 10. Although ethambutol, rifampin, and rifbutin are useful, no official breakpoints are available as there are no strong correlation studies showing the relationship between minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and clinical outcomes.

References

1. Akram SM, Attia FN. Mycobacterium avium Complex. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Fibi Attia declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

2. Miskoff JA, Chaudhri M. Mycobacterium Chimaera: A Rare Presentation. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2750.

3. Murcia MI, Tortoli E, Menendez MC, Palenque E, Garcia MJ. Mycobacterium colombiense sp. nov., a novel member of the Mycobacterium avium complex and description of MAC-X as a new ITS genetic variant. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology. 2006;56(Pt 9):2049-2054.

4. Kwon YS, Koh WJ, Daley CL. Treatment of Mycobacterium avium Complex Pulmonary Disease. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2019;82(1):15-26.

5. Hamed KA, Tillotson G. A narrative review of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: microbiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and management challenges. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2023:1-16.

6. Body BA, Beard MA, Slechta ES, et al. Evaluation of the Vitek MS v3.0 Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry System for Identification of Mycobacterium and Nocardia Species. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2018;56(6).

7. Ichiyama S, Iinuma Y, Yamori S, Hasegawa Y, Shimokata K, Nakashima N. Mycobacterium growth indicator tube testing in conjunction with the AccuProbe or the AMPLICOR-PCR assay for detecting and identifying mycobacteria from sputum samples. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1997;35(8):2022-2025.

8. Hernandez AG, Brunton AE, Ato M, et al. Use of Anti-Glycopeptidolipid-Core Antibodies Serology for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Mycobacterium avium Complex Pulmonary Disease in the United States. Open forum infectious diseases. 2022;9(11):ofac528.

9. Gordin FM, Cohn DL, Sullam PM, Schoenfelder JR, Wynne BA, Horsburgh CR, Jr. Early manifestations of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease: a prospective evaluation. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1997;176(1):126-132.

10. CLSI. [Performance Standards for Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardia spp., and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes, 1st ed. CLSI M62. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018

-Dr. Abdelrahman Dabash is currently a PGY-2 pathology resident at George Washington University. He was born in Dakahlia, Egypt, and was raised in Al-Khobar, KSA. He attended the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University, where he received his doctorate degree. He worked as an NGS analyst for 2 years prior to coming to GWU. His academic interests include Gastrointestinal pathology, hematopathology, and molecular pathology. In his spare time, he enjoys playing soccer, swimming, engaging in outdoor activities, and writing Arabic calligraphy. Dr. Dabash is pursuing AP/CP training.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.