Case History

A 73 year old male with a complex medical history, including type 1 diabetes, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, glaucoma, previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), presented with bilateral persistent paraspinal neck pain, shaking chills, and myalgias. The initial evaluation involved broad laboratory and imaging work-up, which showed mildly elevated CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Chest X-ray, CTA head/neck, and CT thorax were normal. The patient was discharged with symptoms resolved using Tylenol and Valium, and instructions for follow-up care were provided. Two days later, the patient was recalled to the ED after blood cultures were positive for gram positive cocci in pairs and chains. The patient, asymptomatic at the time, was informed of the findings and agreed to return for further evaluation.

The patient had undergone a tooth extraction followed by implant placement one month prior, raising concerns for endocarditis due to prosthetic valve and pacemaker. He was transferred to the cardiology service, and repeat cultures were ordered. Initially afebrile, he later developed a fever (101.7°F), and his condition was complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and septic shock requiring ICU admission. The patient was treated with IV Vancomycin 1.5 g q24h and recommended to have repeat blood cultures until clearance. The discharge diagnosis was bacteremia caused by Abiotrophia defectiva, with a possible prosthetic valve endocarditis. A six-week course of Vancomycin was prescribed.

Discussion

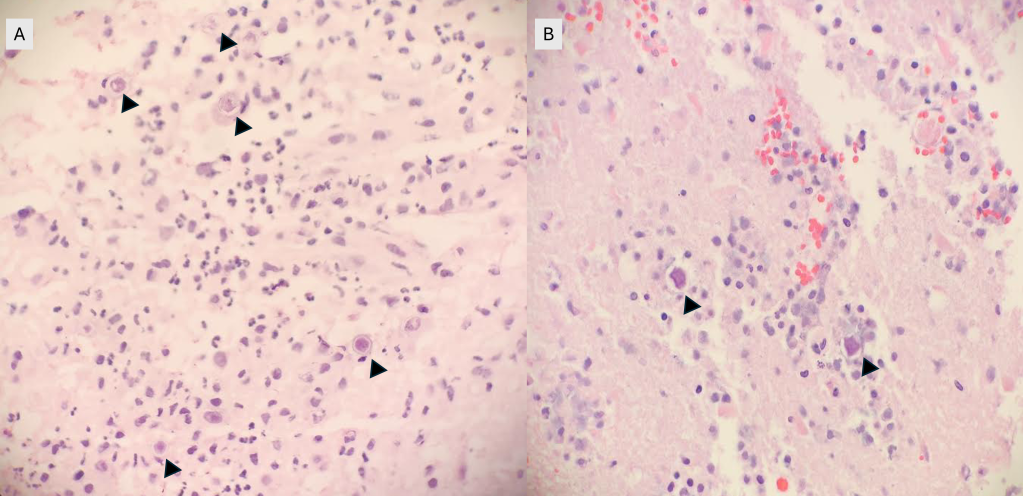

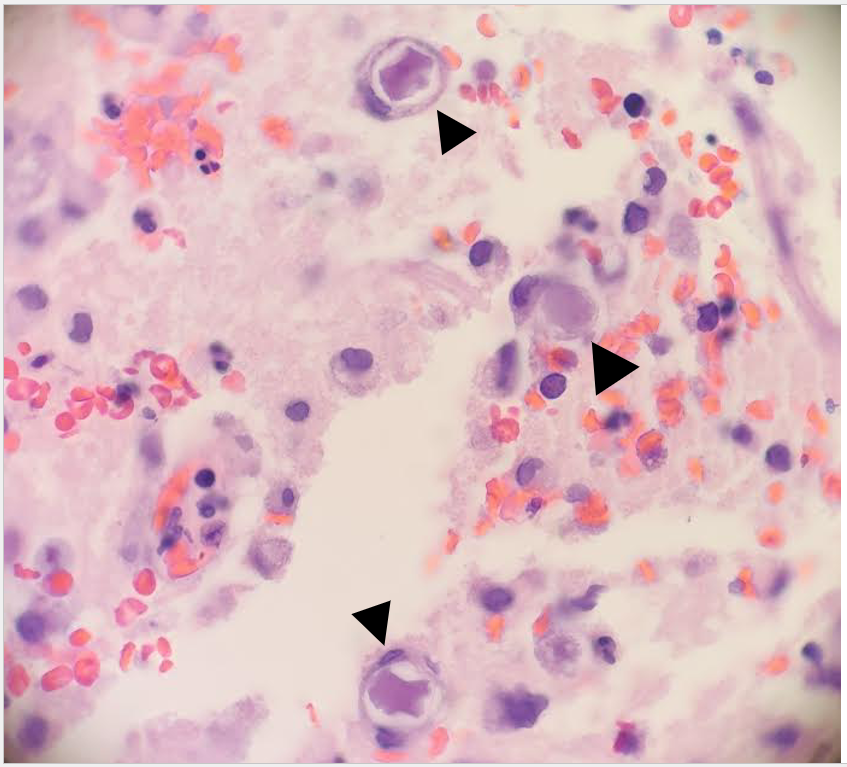

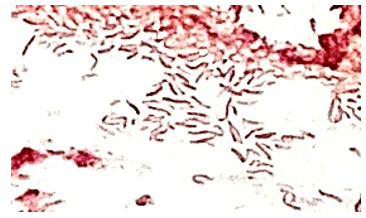

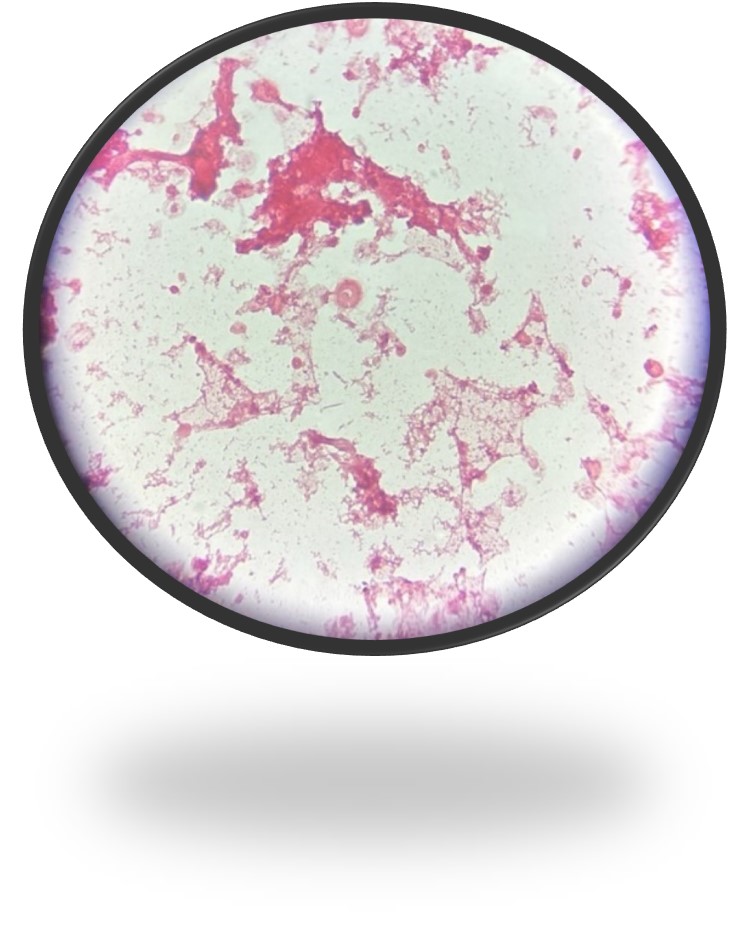

The genus Abiotrophia most resembles well-known gram positive cocci in chains and pairs such as streptococci and enterococci. Abiotrophia were originally thought to be a relative of the viridans Group Streptococcus but sequencing analysis created a new genus called Abiotrophia which consisted of two species, A. defective and A. adiacens.1 Abiotrophia is classified as nutritionally variant streptococcus (NVS) and is a part of normal flora in the intestinal tract, oral cavity, and urogenital tract. The organism accounts for up to 6% of streptococcal infective endocarditis and have been associated with native and prosthetic valve infection.2 Other types of infections that have been described for Abiotrophia include sepsis, infections of the eye, central nervous system, musculoskeletal, and arthritis.3-6 It is crucial to recognize A. defectiva for timely and effective treatment, given its propensity to cause severe complications like septic embolization.7

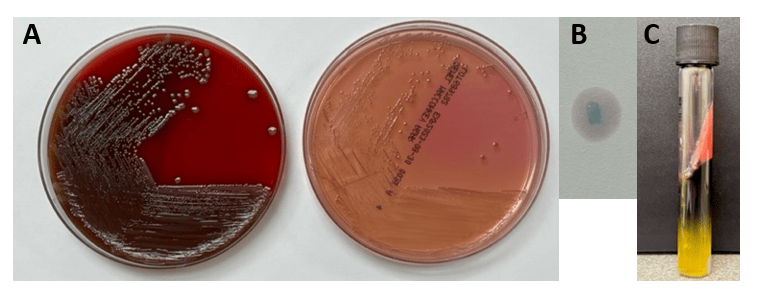

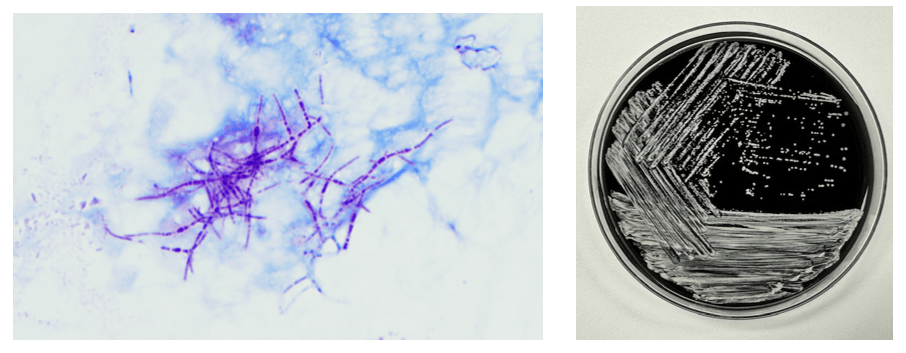

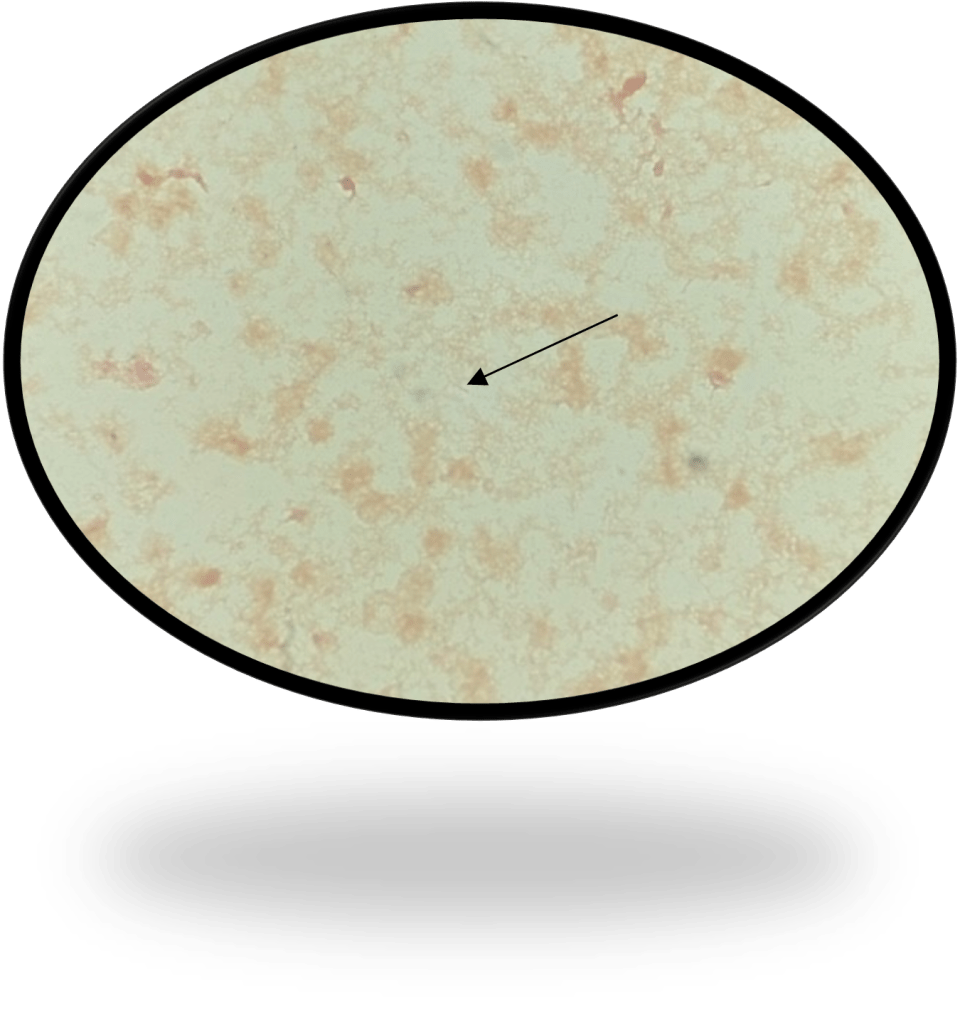

Abiotrophia is coined a NVS because this microorganism requires specific nutrients like L-cysteine or pyridoxal for growth on sheep’s blood agar. They can usually grow without supplementation on chocolate agar, brucella agar with 5% horse blood, and in thioglycolate broth. Sometimes sheep’s blood agar supplemented with pyridoxal can also be used. Due to the release of specific nutrients by lysed red blood cells, the satellite test is important for growth and identification. Briefly, the suspected isolate is streaked for confluent growth on an agar that does not support growth for Abiotrophia (such as sheep’s blood agar) and then overlaid with a cross streak of beta-hemolytic Staphylococcus aureus. After incubation, colonies of Abiotrophia can grow near the S. aureus streak, giving rise to the ‘satellite’ phenomenon. However, it should be noted that other fastidious organisms such as Granulicatella and some Haemophilus species can also satellite around the S. aureus streak. Hence, further confirmation is needed for identification. For example, Abiotrophia is non-motile. Common biochemicals reactions to help characterize Abiotrophia genus is PYR (production of pyrrolidonyl arylamidase) positive, LAP (production of leucine aminopeptidase) positive, and no growth in 6.5% NaCl.

Molecular approaches have been proven to be accurate for identification of Abiotrophia . Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene have shown to be more accurate than phenotypic, biochemical tests. PCR testing for the rpoB, groESL, and also the ribosomal 16S-23S intergenic spacer region (ITS) genes have all shown to be reliable targets for identification.8-10 The introduction of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry has facilitated more accurate identification in clinical settings.11

Prompt diagnosis and targeted antimicrobial therapy are essential in managing infections caused by Abiotrophia defectiva, especially in older patients with underlying health conditions. Early detection and appropriate treatment are vital to mitigate potential complications.6,7 Abiotrophia species exhibit varying antibiotic susceptibility, with increasing resistance to penicillin. Common treatments include penicillin, ceftriaxone, and vancomycin.

References

1. Kawamura, Y., et al., Transfer of Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus to Abiotrophia gen. nov. as Abiotrophia adiacens comb. nov. and Abiotrophia defectiva comb. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Bacteriol, 1995. 45(4): p. 798-803.

2. Christensen, J.J. and R.R. Facklam, Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol, 2001. 39(10): p. 3520-3.

3. Niu, K. and Y. Lin, Abiotrophia defectiva Endocarditis Complicated by Stroke and Spinal Osteomyelitis. Cureus, 2024. 16(3): p. e56904.

4. Wilhelm, N., et al., First case of multiple discitis and sacroiliitis due to Abiotrophia defectiva. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2005. 24(1): p. 76-8.

5. Taylor, C.E. and M.A. Fang, Septic arthritis caused by Abiotrophia defectiva. Arthritis Rheum, 2006. 55(6): p. 976-7.

6. Yang, M., et al., Abiotrophia defectiva causing infective endocarditis with brain infarction and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Front Med (Lausanne), 2023. 10: p. 1117474.

7. Faria, C., et al., Mitral Valve Subacute Endocarditis Caused by Abiotrophia Defectiva: A Case Report. Clin Pract, 2021. 11(1): p. 162-166.

8. Drancourt, M., et al., rpoB gene sequence-based identification of aerobic Gram-positive cocci of the genera Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella. J Clin Microbiol, 2004. 42(2): p. 497-504.

9. Hung, W.C., et al., Use of groESL as a target for identification of Abiotrophia, Granulicatella, and Gemella species. J Clin Microbiol, 2010. 48(10): p. 3532-8.

10. Tung, S.K., et al., Identification of species of Abiotrophia, Enterococcus, Granulicatella and Streptococcus by sequence analysis of the ribosomal 16S-23S intergenic spacer region. J Med Microbiol, 2007. 56(Pt 4): p. 504-513.

11. Christensen, J.J., et al., Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry analysis of Gram-positive, catalase-negative cocci not belonging to the Streptococcus or Enterococcus genus and benefits of database extension. J Clin Microbiol, 2012. 50(5): p. 1787-91.

-Maher Ali, MD was born in and raised in Amman, Jordan. He attended Jordan University of Science and Technology, where he received his doctorate degree. After graduation, he completed two years of anatomic pathology residency at King Hussein Cancer Center in Jordan. He then relocated to the United States to start his combined anatomic and clinical pathology (AP/CP) training at The George Washington University. His academic interests include gastrointestinal and breast pathology. Outside of the hospital, he enjoys cooking, hiking, exploring new restaurants, and spending quality time with his family and friends.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics. She is also a top 5 honoree among the 2023 ASCP 40 Under Forty.