Background

A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, antibiotic resistance has increased by at least 15%. In particularly, the extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBLs) producing Enterobacterales have gone up to 32%. This group includes E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca and P. mirabilis.1

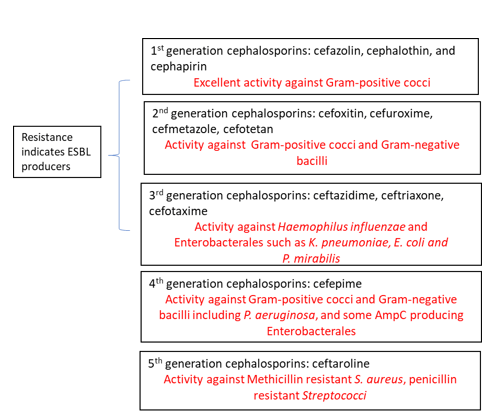

ESBLs are β-lactamases capable of conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins, first, second and third generation cephalosporins and aztreonam (but not cephamycins or carbapenems) (Table 1). A key characteristic is that these enzymes hydrolyze the antibiotics but are inhibited by β -lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid, tazobactam and sulbactam. Thus, diagnostic assays utilize this key characteristic to develop tools to screen for ESBL producers as discussed below.1-3

The genes encoding ESBLs are found on plasmids which enable rapid and easy transfer between Enterobacterales and some non-Enterobacterales as well. TEM-1, one of the first plasmid encoded β-lactamase enzymes, was identified in E. coli. Another one, SHV1 was subsequently discovered in Klebsiella.2 These original β-lactamases were narrow spectrum, but mutations have led to enzymes with broad spectrum activity, hydrolyzing many of the commonly used antibiotics. Today, there are over 100 variations of these enzymes that have spread resistance worldwide. The most dominant ESBL today is CTX-M, an enzyme that originated from Kluyvera species. CTX-M encoded resistance has now been reported among Enterobacterales as well as P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter sp.2 Other ESBL families include IRT, CMT, GES, PER, VEB, BEL, TLA, SFO, and OXY.4

Detection of ESBL producers

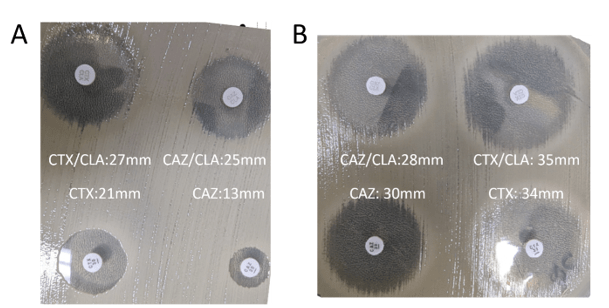

The most common method for ESBL screening is the disk diffusion assay with clavulanic acid and cefotaxime and/or ceftazidime also called the double disc synergy test5 (Figure 1). ESBL producers are resistant to cefotaxime and ceftazidime. However, presence of clavulanic acid recovers the activity of cefotaxime and ceftazidime making the organism susceptible. If the activity of either one of these 3rd generation cephalosporin is recovered by clavulanic acid, then the presence of an ESBL is confirmed. A positive ESBL interpretation is resulted when there is ≥5 mm increase in zone diameter for either agent tested in combination with clavulanate versus the zone diameter of the agent tested alone. A broth microdilution approach is also possible. A positive ESBL interpretation would be a ≥3 ‘2-fold’ concentration decreases in an MIC for either agent tested in combination with clavulanate versus the MIC of the agent tested alone. Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI) guidance does not require ESBL testing for Enterobacterales but testing is recommended for infection prevention or specific institutional practices. For reporting of cephalosporin results, if current breakpoints are used for one or more cephalosporins, it is advised that the MICs are reported per usual. However, if obsolete cephalosporin breakpoints are used, then all penicillins, cephalosporins and aztreonam should be reported as resistant.6 It should be noted that there may be trivial differences between CLSI and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines and it is up to the individual institution to decide which guidelines to follow.

Other phenotypic based methods to detect for ESBLs include commercially available testing systems that have built in phenotypic ESBL screening. Performance varies depending on the manufacturer and ranges from 84-99% and 52-78% for sensitivity and specificity, respectively.7 Other commercially available assays include the colorimetric tests such as the Rapid ESBL Screen Kit (Rosco Diagnostica) that detects ESBL producers without differentiating between the various enzymes.5,8 This test has sensitivity of >90% when tested with cultured isolates or various specimens (blood, urine or respiratory) but variable specificity. There is also a lateral flow test (NG-Test CTX-M MULTI assay, NG Biotech, Guipry, France) developed to detect for CTX-M enzymes with reported sensitivity and specificity of >98%.9

Advancements in molecular testing have included ESBL genes as targets on commercially available diagnostic panels. As CTX-M is the most common and wide-spread ESBL gene, commercial, FDA-approved platforms including blood culture identification panels and pneumonia panels include the CTX-M marker as a target. Sensitivity ranging from 85-95% have been reported with variable specificity.10-12 Recently, the Acuitas AMR gene panel became the first FDA-cleared diagnostic test that includes a wide panel of 28 AMR markers including ESBL-related family of genes such as TEM and SHV with reported positive predictive agreement of 98.5% and 100%, respectively.13

Overall, there are various methods to detect for ESBL producers and detection for ESBL producers may not be a straightforward matter as there are many ESBL families of genes and in general, antibiotic resistance mechanisms in gram negative organisms are heterogeneous. However, given the rise in antimicrobial resistance, identification of ESBL producers is vital both in treatment of patients as well as surveillance.

REFERENCES

1. CDC. 2022. Special report – Covid-19 U.S. Impact on antimicrobioal resistance.

2. Castanheira M, Simner PJ, Bradford PA.2021. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC Antimicrob Resist 3:dlab092.

3. Jacoby GA.2009. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:161-82, Table of Contents.

4. Castanheira M, Simner PJ, Bradford PA.2021. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC Antimicrob Resist 3:dlab092.

5. Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P.2015. Rapid detection of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in blood cultures. Emerg Infect Dis 21:504-7.

6. Fay D, Oldfather JE.1979. Standardization of direct susceptibility test for blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol 9:347-50.

7. Wiegand I, Geiss HK, Mack D, Stürenburg E, Seifert H.2007. Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae by use of semiautomated microbiology systems and manual detection procedures. J Clin Microbiol 45:1167-74.

8. Rood IGH, Li Q.2017. Review: Molecular detection of extended spectrum-beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a clinical setting. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 89:245-250.

9. Bernabeu S, Ratnam KC, Boutal H, Gonzalez C, Vogel A, Devilliers K, Plaisance M, Oueslati S, Malhotra-Kumar S, Dortet L, Fortineau N, Simon S, Volland H, Naas T.2020. A Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid Identification of CTX-M-Producing Enterobacterales from Culture Plates and Positive Blood Cultures. Diagnostics (Basel) 10.

10. Murphy CN, Fowler R, Balada-Llasat JM, Carroll A, Stone H, Akerele O, Buchan B, Windham S, Hopp A, Ronen S, Relich RF, Buckner R, Warren DA, Humphries R, Campeau S, Huse H, Chandrasekaran S, Leber A, Everhart K, Harrington A, Kwong C, Bonwit A, Dien Bard J, Naccache S, Zimmerman C, Jones B, Rindlisbacher C, Buccambuso M, Clark A, Rogatcheva M, Graue C, Bourzac KM.2020. Multicenter Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia/Pneumonia Plus Panel for Detection and Quantification of Agents of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. J Clin Microbiol 58.

11. Peri AM, Ling W, Furuya-Kanamori L, Harris PNA, Paterson DL.2022. Performance of BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel (BCID2) for the detection of bloodstream pathogens and their associated resistance markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. BMC Infect Dis 22:794.

12. Klein M, Bacher J, Barth S, Atrzadeh F, Siebenhaller K, Ferreira I, Beisken S, Posch AE, Carroll KC, Wunderink RG, Qi C, Wu F, Hardy DJ, Patel R, Sims MD.2021. Multicenter Evaluation of the Unyvero Platform for Testing Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid. J Clin Microbiol 59.

13. Simner PJ, Musser KA, Mitchell K, Wise MG, Lewis S, Yee R, Bergman Y, Good CE, Abdelhamed AM, Li H, Laseman EM, Sahm D, Pitzer K, Quan J, Walker GT, Jacobs MR, Rhoads DD.2022. Multicenter Evaluation of the Acuitas AMR Gene Panel for Detection of an Extended Panel of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes among Bacterial Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 60:e0209821.

-Athulaprabha Murthi PhD is currently a Fellow at the NYC Public Health Laboratory. She is interested in antibiotic resistance and hopes to work towards better diagnostic testing and surveillance methods for monitoring resistance. She also enjoys writing and teaching whenever opportunity presents.

-Rebecca Yee, PhD, D(ABMM), M(ASCP)CM is the Chief of Microbiology, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory at the George Washington University Hospital. Her interests include bacteriology, antimicrobial resistance, and development of infectious disease diagnostics.

I think Table 1 is quite useful but I would add an asterisk to cefoxitin and cefotetan and add that *these are cephamycins and can be reported as susceptible if disc diffusion indicates this to be the case.

Cefmetazole, cefotetan, and cefoxitin are cephamycins, ESBLs do not confer resistance to them (table 1)