Case History

A 3-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department 1 day following a provoked dog bite to the right cheek. At home, the bite area was cleaned, but it subsequently developed progressive erythema, swelling, and purulent discharge. Review of systems was otherwise negative. Both the patient and dog were up-to-date on vaccinations. On exam, the patient displayed a 1 cm area of induration with surrounding erythema and actively draining whitish fluid.

Fluid from the draining wound was sent to the microbiology laboratory for Gram stain and culture. On Gram stain, rare gram-negative rods were identified, as well as few polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The following organism was recovered from culture the next day.

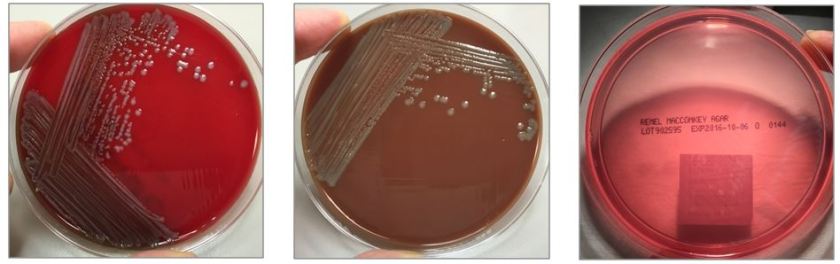

Figure 1: Growth on blood, chocolate and MacConkey agars. Note one larger and one smaller colony morphology growing on blood and chocolate agars. The organism did not grow on MacConkey agar.

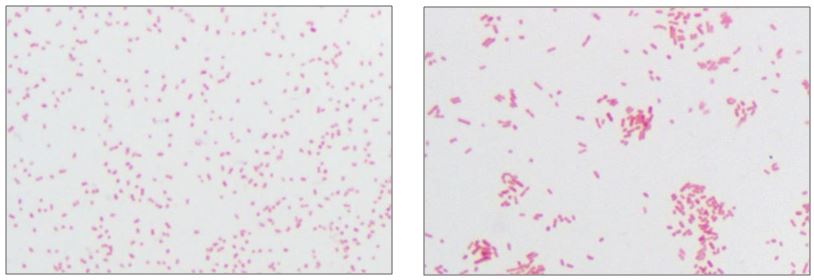

Figure 2. Subcultures of the two distinct colony types. The larger colonies (left) appeared more mucoid than the smaller colonies (right).

Figure 3. Gram stains of the two colony types revealed a small, Gram-negative coccobacilli identified as Pasteurella multocida (right) and a larger, pleomorphic Gram-negative rod identified as Pasteurella canis (left).

Laboratory Work-Up

The specimen was cultured on 5% sheep blood, chocolate, and MacConkey agars. Two colony morphologies emerged on the blood and chocolate agar plates (Figure 1). The organism did not grow on MacConkey agar. Representatives of each colony morphology were subcultured onto 5% sheep blood agar with growth shown in Figure 2. One colony is larger and mucoid (Figure 2, left) while the second is smaller and non-mucoid (Figure 2, right).

MALDI-TOF (Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight) identified two different species of Pasteurella. Colony Gram stains show P. multocida as small Gram-negative coccobacilli (Figure 3, right) and P. canis as pleomorphic Gram-negative rod (Figure 3, left).

Discussion

The Pasteurella spp. are non-motile, facultatively anaerobic, Gram-negative coccobacilli found in the respiratory tracts of nonhuman mammals, most notably cats and dogs. By current classification the genus includes P. multocida (with 3 subspecies), P. dagmatis, P. canis, and P. stomatis, with P. multocida being the most common human pathogen and species recovered from animals (>70% carriage in cats, >40% in dogs) [1]. The foremost human infection is bite or scratch wound with cellulitis, with rapid development of erythema, swelling, and purulent drainage as observed in this case. Licking may also transmit the bacteria. Possible associated findings include fever and regional lymphadenopathy. More serious potential infections include osteomyelitis, septic joint, endocarditis, bacteremia, sepsis, and meningitis. Systemic illness typically requires immunocompromise (classically liver disease). The organisms are generally penicillin-sensitive [2].

Key identification features of Pasteurella spp. include oxidase positivity and failure to grow on MacConkey agar, both differentiating Pasteurella from the Enterobacteriaceae. Other common features include and catalase and indole positivity. Unlike other certain fastidious gram negative bacteria (e.g., Haemophilus), Pasteurella grow independently on blood agar without the requirement for hemin or NAD. Of note, Capnocytophaga spp. (also associated with dog bites) also grows on blood and chocolate but not MAC. However, Capnocytophaga require a CO2-enriched environment and the Gram stain is notably different as they are long, slender Gram-negative rods [1].

This case was notable for a dual Pasteurella infection, an uncommon but previously reported phenomenon [3]. The organisms differed by colony morphology, with P. multocida appearing larger and mucoid (reflecting capsule production) on the blood agar, and P. canis appearing smaller, grey, and non-mucoid. Capsule is a key virulence factor of P. multocida and tends to be associated with more severe infections [4].

The patient was treated with a 10 day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate and has completely recovered.

References

- Procop, G. W., Church, D. L., Hall, G. S., Janda, W. M., Koneman, E. W., Schreckenberger, P. C., & Woods, G. L. (2016). Koneman’s Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

- Graevenitz, A., & Zbinden, R. (n.d.). Actinobacillus, Capnocytophaga, Eikenella, Kingella, Pasteurella, and Other Fastidious or Rarely Encountered Gram-Negative Rods. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 10th Edition (pp. 574–587). American Society of Microbiology.

- Holst, E., Rollof, J., Larsson, L., & Nielsen, J. P. (1992). Characterization and distribution of Pasteurella species recovered from infected humans. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 30(11), 2984–7.

- Harper, M., Boyce, J. D., & Adler, B. (2006). Pasteurella multocida pathogenesis: 125 years after Pasteur. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 265(1), 1–10.

-William Phipps, M.D., 1st year Anatomic and Clinical Pathology Resident, UT Southwestern Medical Center

-Erin McElvania TeKippe, Ph.D., D(ABMM), is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas Texas and an Assistant Professor of Pathology and Pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

This was very interesting and a great review.

I agree