Case history

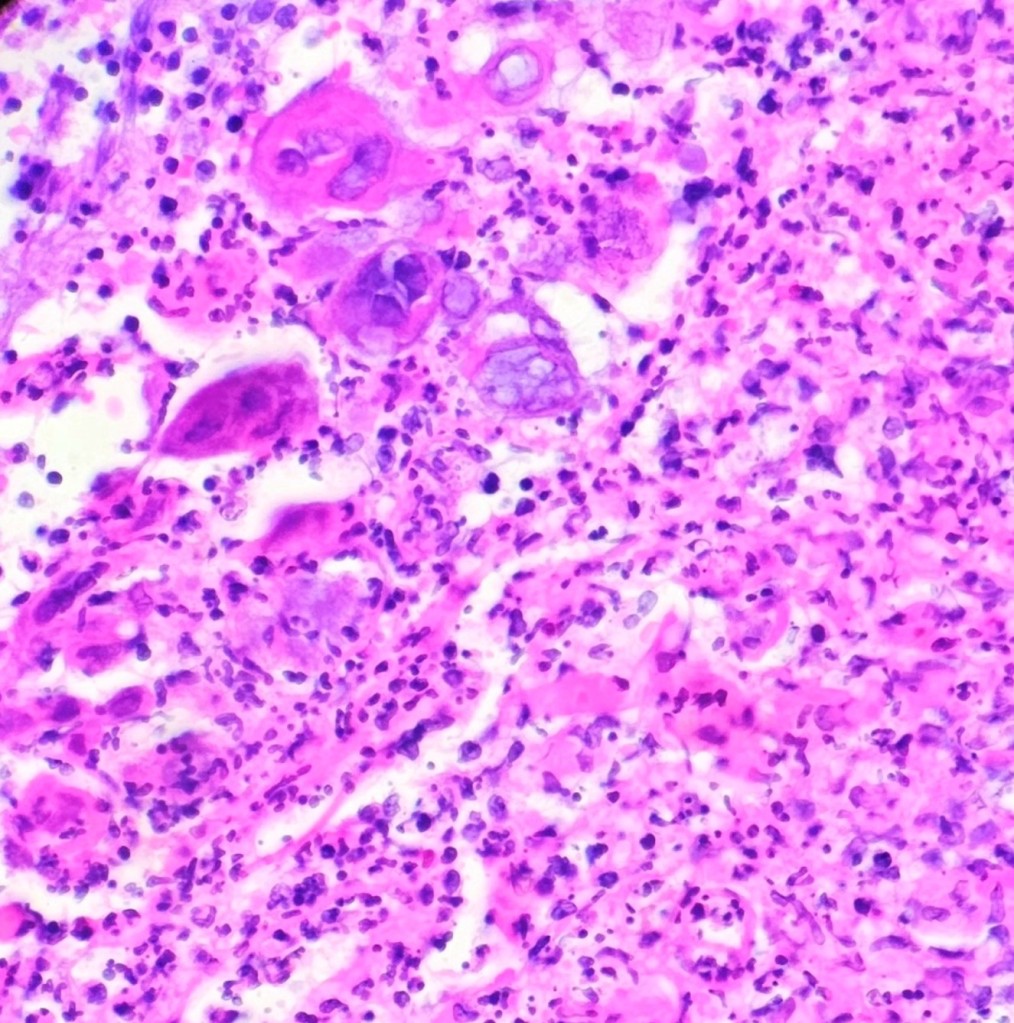

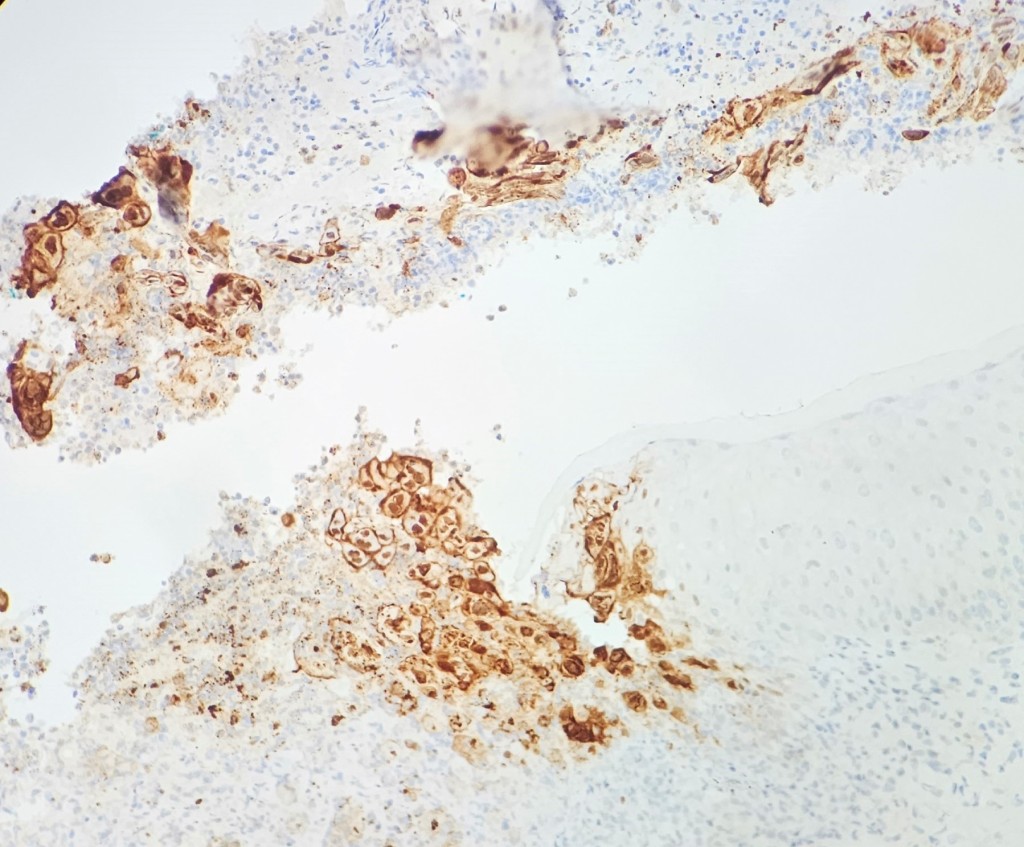

A 37-year-old female with a past medical history of psoriasis and common variable immunodeficiency disorder (CVID) presented to her dermatologist for an ulceration on her right buttock following a camping trip about 1 month ago. She thought that she had been bitten by a bug, for the lesion became extremely pruritic and painful. The patient was self-treating the area with over-the-counter antibiotic ointment and an anti-itch cream, but the symptoms persisted. At the time, the dermatologist was also treating a lower extremity dermatophyte infection, and the antibiotic cream and anti-itch cream were discontinued and replaced with clobetasol 0.05% ointment for potential allergic dermatitis. The patient returned to the dermatologist about a month later as the site was becoming increasingly inflamed and painful. The patient had also started experiencing night sweats and fever, so she was transferred and further evaluated in the emergency department. In the ED, the differential included soft tissue infection, cellulitis, or abscess of a fungal, viral, or bacterial etiology. Labs showed evidence of inflammation with an elevated ESR and CRP. A punch biopsy was performed and pathologic examination showed an ulcer bed with prominent acute inflammatory cell infiltrate and necrosis. The infected squamous epithelium showed the3 Ms findings (Molding, Margination, Multinucleation) consistent with herpetic infection (figure 1). The diagnosis was confirmed with HSV complex IHC (figure 2) and PCR testing of the lesion came back positive for HSV-2. Of note, the patient did have a history of genital herpes; however, she was not having a typical flare, and she had been treated with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 2 weeks prior to her ED visit. The gram stain showed no evidence of neutrophils, squamous epithelial cells, or organisms, but bacterial cultures came back positive for MRSA.

showing herpes viral cytopathic effect (400x magnification)

Discussion

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a large, double-stranded DNA virus from the Herpesviridae family.1,2 HSV-2 is generally considered a sexually transmitted infection because it can be transmitted by contact with infected genital secretions.2,3 The viral particles within these secretions can enter epithelial cells and begin replicating, causing the characteristic intranuclear inclusions and multinucleated giant cells that can be seen under the microscope.2 When the virus infects the cells in this manner, it can also cause these infected cells to separate from each other and form grouped vesicles filled with these cell remnants.2 The virus infects nerve endings and then travels backwards to the sacral ganglia, and it can remain latent there permanently, giving it the ability to recur during the infected person’s lifetime.1 A patient can initially present with symptoms of dysuria, lymphadenopathy, fever, headaches, and myalgias, but more than half of patients may not know they have genital herpes.1,3 Recurrences can present with symptoms of tingling, burning, itching, and pain in the nerve’s distribution pattern, similar to the pain and pruritis in our presented case.2 When there is a suspected HSV infection, PCR for HSV DNA is generally the best diagnostic tool, and it is faster and more sensitive than viral culture.1,2 A patient with known herpes infection should be treated with antivirals; however, the lesions should also self-resolve within 3 weeks if the patient is not treated.1

One abnormality in our presented case was that the patient’s reactivation of genital herpes was on the buttocks. A repeat infection with HSV at a site other than genitalia is more common when the primary infection also occurred at a site other than the genitalia.4 Infections occurring at non-genital sites such as the buttocks can also occur due to self-inoculation, which may have been the case in our patient.4 Additionally, repeat infections with HSV in non-genital sites are more common when the initial infection was with HSV1, but our patient’s PCR showed the presence of HSV-2 DNA.4 One explanation for this phenomenon is that HSV-2 recurrences can occur on the buttocks due to the retrograde transport to the root ganglia in the areas that correspond to these dermatomes.4

Another abnormality in our presented case involves the patient’s persistent infection despite treatment with a course of valacyclovir for 10 days. Generally, an initial herpes infection self-resolves in a matter of weeks, and a recurrent episode will self-resolve in a matter of days, usually less than ten.1,2 It is unusual that her infection persisted despite therapy, but the patient does have a medical history significant for CVID. Patients with weakened immune systems can take longer to fight off herpes infections even if they are taking antivirals.2 Additionally, there is a theory that herpes buttocks infections last longer than in other regions due to the greater travel distance along the nerves as well as a higher concentration of nerve endings in this region.4 The patient in our case also had tissue cultures that were positive for MRSA, meaning she had a concomitant bacterial and viral infection of the buttock region, and treatment with an antiviral would not be sufficient to eradicate her coinfection.

References

1. Johnston C, Corey L. Current Concepts for Genital Herpes Simplex Virus Infection: Diagnostics and Pathogenesis of Genital Tract Shedding. Clin Microbiol Rev. Jan 2016;29(1):149-61. doi:10.1128/cmr.00043-15

2. Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. Dec 22 2007;370(9605):2127-37. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61908-4

3. Groves MJ. Genital Herpes: A Review. Am Fam Physician. Jun 1 2016;93(11):928-34.

4. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, Corey L. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. Mar 1995;98(3):237-42. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80369-6

-Lillian Acree is a fourth-year medical student at the Medical College of Georgia. She is interested in head and neck pathology.

-Hasan Samra, MD, is the Director of Clinical Microbiology at Augusta University and an Assistant Professor at the Medical College of Georgia.