Presenting History

A 62 year old male, former smoker, with status post double lung transplant three months prior, presented to the lung transplant clinic for a follow-up appointment in July complaining of shortness of breath, which had worsened over the past 3 weeks and prompted the need for O2 again with minimal daily activities. He denies any chest pain, fevers, headaches, dizziness, N/V/D. He was admitted for further management of possible organ rejection and worsening respiratory function tests.

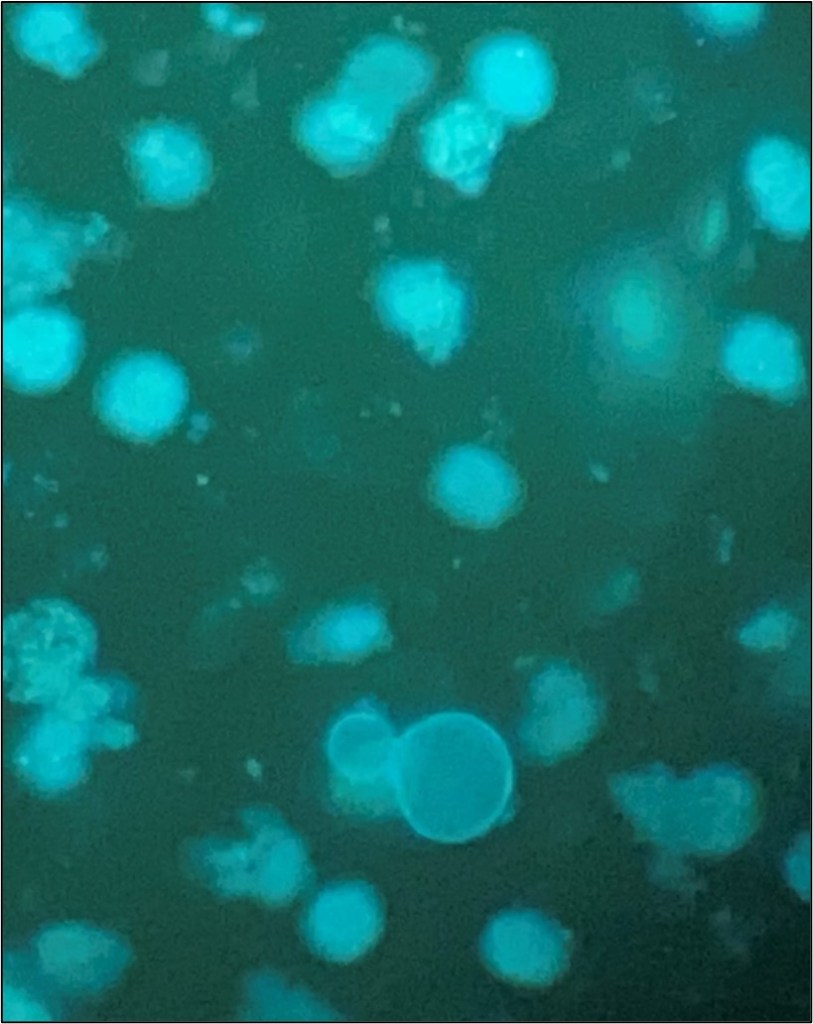

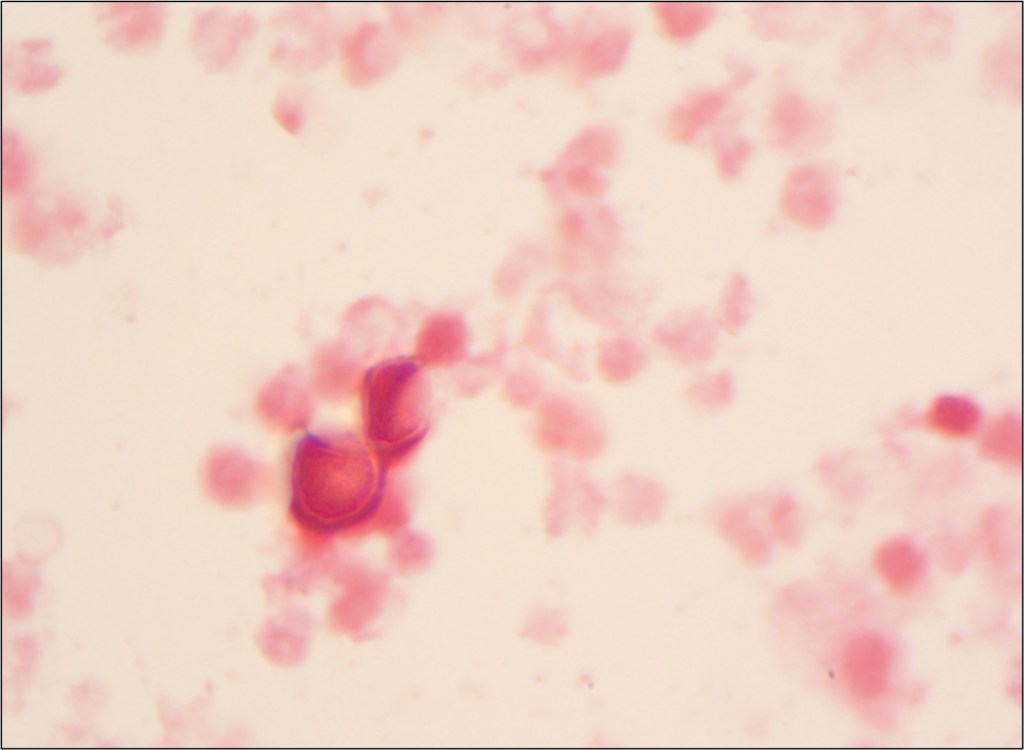

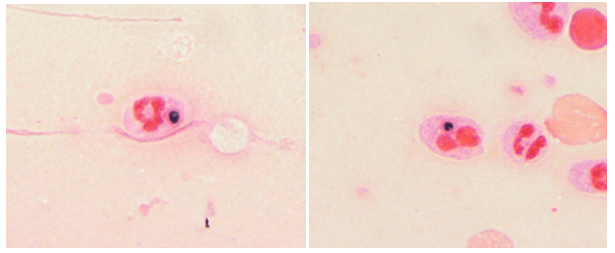

The patient was started on IV solumedrol followed by a prednisone taper. A chest CT (non-contrast) showed patent bronchial anastomoses and stable bilateral small right greater than left loculated pleural effusions. Respiratory pathogen panel results were negative, and Cryptococcus Antigen and titer were negative. He then underwent bronchoscopy and biopsy, showing no signs of rejection. BAL was sent to microbiology for cultures. Fungal culture grew 3 days after incubation (Fig 1), and the Lactophenol cotton blue (LCB) prep shows septate hyphae with long and short conidiophores in small groups, which was identified as Scedosporium spp.

Discussion

Scedosporium apiospermum is an environmental mold increasingly reported as an opportunist organism due to the increasing use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, antineoplastics, and indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.1 The organism can cause various diseases, including colonization in cystic fibrosis, neurological infection associated with near-drowning incidents, and disseminated disease in immunocompromised individuals.2,3

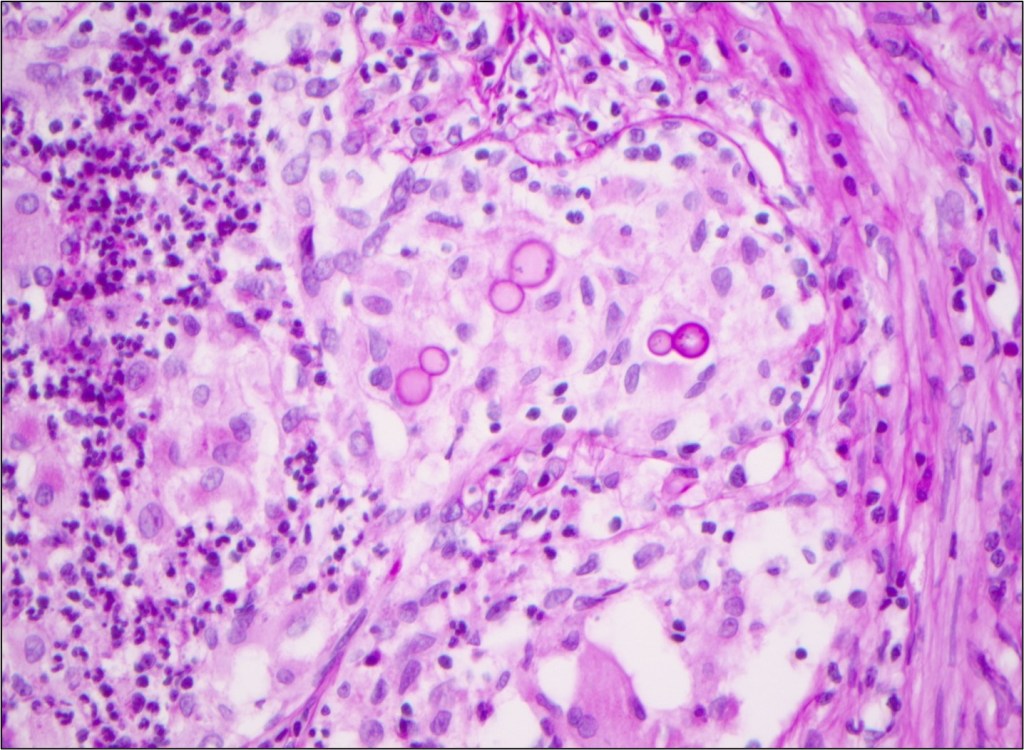

Laboratory diagnosis of a Scedosporium infection is primarily based on the histopathologic exam from a direct specimen or microscopic examination of lactophenol cotton blue prep of fungal culture growth combined with the clinical or radiographic findings suggesting infection. Since the microconidia of Scedosporium could resemble Blastomyces spp, care should be taken to rule out the dimorphic mold. Scedosporium grows well and faster than Blastomyces on routine mycological media such as Sabouraud’s glucose agar, blood agar, and chocolate agar. Patient’s travel/demographic history is particularly important since Blastomyces is commonly found in Ohio and Mississippi River Valley regions and endemic in Southcentral and Southeastern US whereas Scedosporium is ubiquitous.4

Scedosporium growth is also observed on the media with a high concentration of cycloheximide5 which is inhibitory for clinical Aspergillus species. A competing fungal flora of rapidly growing Aspergillus and Candida species is frequently present. Isolation using benomyl agar6 or cycloheximide-containing agar is then recommended. Culture of sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or secretions from the trachea or external ears, particularly in CF patients, may be hampered by their mucoid consistency.

Typically, fungal identification is achieved primarily via microscopic examination in clinical microbiology laboratories. At the same time, more laboratories have adopted matrix-assisted laser-desorption-ionization Time-of-Flight (MALDI-ToF) for more accurate and rapid identification. Microscopic examination from a fungal culture requires a significantly longer time for mold sporulation. With MALDI-ToF, identification can be achieved rapidly as soon as sufficient growth for protein extraction. Nucleic-acid-based identification methods, such as DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) combined with ITS (Internal transcribed spacer) or 28s rRNA, can also be used for identification directly from clinical samples or the mold grown on culture.7 Histopathologic examination is helpful for determining the presence of invasive mold infection, but it is not possible to establish definitive identification without culture because various hyaline molds have a similar appearance. For this reason, culture is still an essential part of the diagnostic evaluation. Culture is also vital for testing in vitro susceptibility since Scedosporium spp can be resistant to multiple antifungal agents.7

References

[1] Khan A, El-Charabaty E, El-Sayegh S. Fungal infections in renal transplant patients. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:371–8.

[2] K.J. Cortez, E. Roilides, F. Quiroz-Telles, J. Meletiadis, C. Antachopoulos, T. Knudsen, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp Clin Microbiol Rev, 21 (1) (2008), pp. 157-197

[3] W.J. Steinbach, J.R. Perfect Scedosporium species infections and treatments J Chemother, 15 (2003), pp. 16-27

[4] Kim MK, Smedberg JR, Boyce RM, Miller MB. The Brief Case: “Great Pretender”-Disseminated Blastomycosis in Western North Carolina. J Clin Microbiol. 2021 Nov 18;59(12):e0304920. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03049-20. Epub 2021 Nov 18. PMID: 34792387; PMCID: PMC8601235.

[5] Rippon JW. , Medical Mycology. The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes3rd edn, 1998PhiladelphiaSaunders

[6] Summerbell RC. The benomyl test as a fundamental diagnostic method for medical mycology, J Clin Microbiol, 1993, vol. 31 (pg. 572-577)

[7] De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 15;46(12):1813-21. doi: 10.1086/588660. PMID: 18462102; PMCID: PMC2671227.

-Abdon Lopez Torres, M.D., is a second year AP/CP resident of Pathology Department at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY. He completed his medical degree in Saint George’s University in Grenada. He’s interested in pursuing a surgical pathology fellowship after completing his residency.

-Phyu Thwe, Ph.D, D(ABMM), MLS(ASCP)CM is Associate Director of Infectious Disease Testing Laboratory at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY. She completed her medical and public health microbiology fellowship in University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, TX. Her interests includes appropriate test utilization, diagnostic stewardship, development of molecular infectious disease testing, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis.