Case presentation

A middle-aged male with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and alcohol-related cirrhosis presented to the emergency department with altered mental status. He was obtunded, acutely encephalopathic and hypoglycemic. He soon developed emesis and coded during clinical assessment, undergoing emergent intubation. He was found to be profoundly acidotic with labs consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiorgan failure. The patient was transfused but continued to code multiple times before and during ICU transfer/admission. Despite multiple resuscitation attempts, he expired soon afterwords.

Laboratory workup

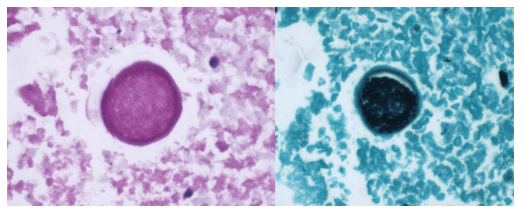

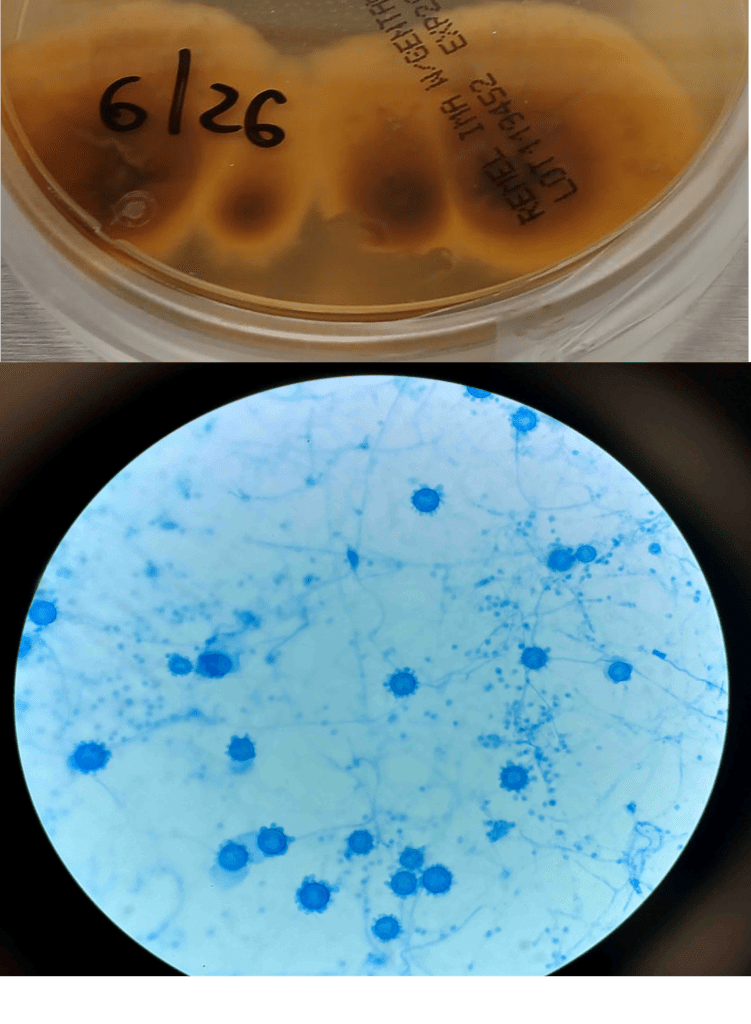

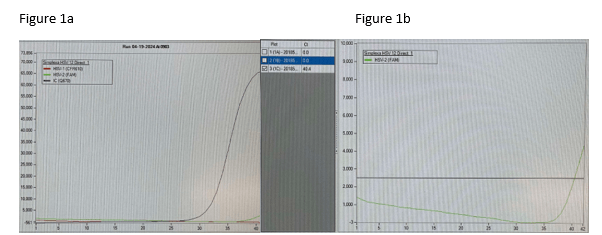

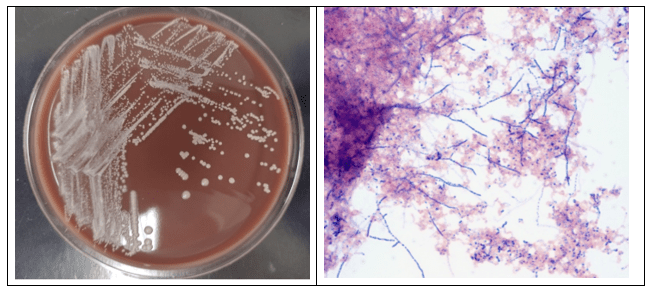

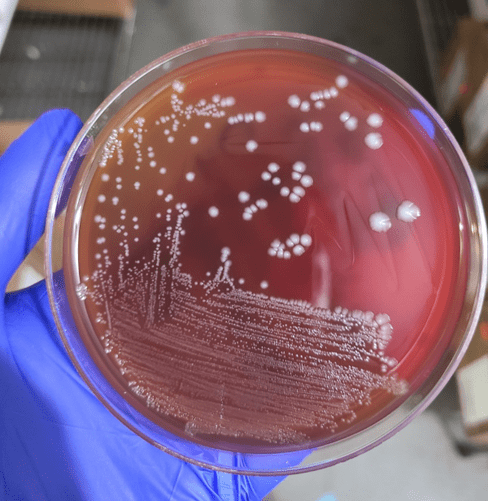

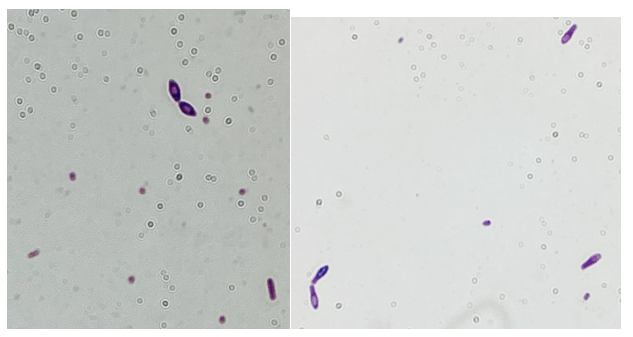

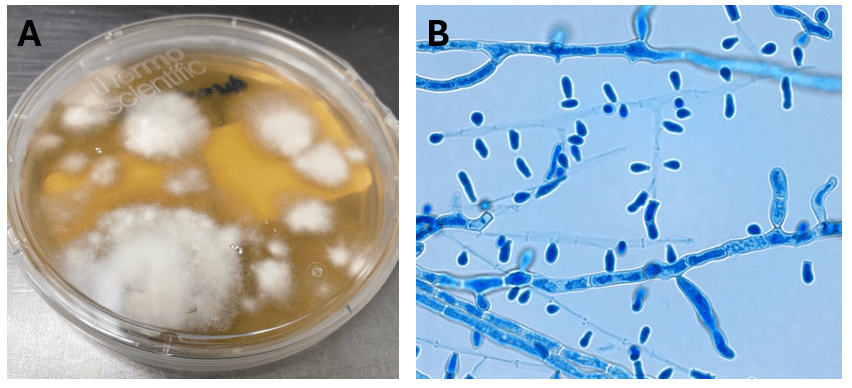

Blood cultures drawn in the ED prior to admission became positive with curved gram-negative rods (Image 1A) within 16 hours. An oxidase-positive, indole-positive, beta-hemolytic organism was recovered after 24 hours of incubation. The organism was lactose-fermenting (confirmed by ONPG) and exhibited colorless growth on Thiosulfate Citrate Bile Salts agar suggestive of a lack of sucrose utilization (Image 1B, set up for demonstrative purposes). The organism was definitively identified as Vibrio vulnificus by MALDI-TOF MS. No additional workup was undertaken as the patient had expired prior to the organism being recovered from blood culture.

Discussion

Vibrio sp. are marine bacteria that naturally colonize brackish and saltwater aquatic environments. Of the more than 70 currently recognized species, at least 12 are recognized as human pathogens.1 Human infections are broadly classified as being either cholera (caused by V. cholerae) or vibriosis (caused by other non-V. cholerae Vibrio spp.). Unlike cholera; a severe diarrheal illness usually acquired through ingestion of contaminated food or water, vibriosis represents a group of infections with varied clinical manifestations dependent upon the etiologic agent, route of infection, and host susceptibility.2 Non-cholera vibrios are often found in seawater with moderate to high salinity and as clinically important contaminants of raw or undercooked seafood.

V. vulnificus thrives in warmer water and infections follow a seasonality, peaking in the warmer summer months.3 In contrast to V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus infections generally are associated with patients with underlying conditions, most commonly diabetes, liver disease and iron storage disorders. It is estimated that patients with chronic liver diseases (particularly cirrhosis due to either alcoholism or chronic hepatitis B or C) are 80-fold more likely to develop V. vulnificus-associated primary septicemia than healthy counterparts.2 Infections are most common in men aged 45-60 years who make up 85-90% of patients,4 consistent with this case. Contaminated food consumption (particularly filter feeding shellfish) can result in gastroenteritis or primary septicemia and disseminated disease.

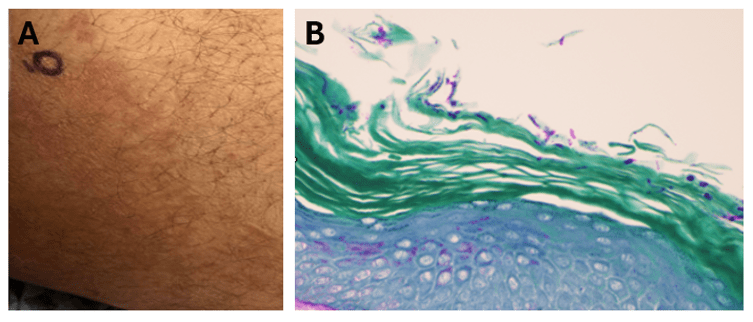

Non-cholera vibrios are estimated to cause up to 80,000 infections worldwide, with V. parahaemolyicus and V. alginolyticus responsible for most cases. Among this group of organisms, V. vulnificus stands out as being particularly virulent; between 150-200 V. vulnificus infections are reported to the US CDC annually, with 20% being fatal.5 This organism oftencauses more than 95% of seafood-related deaths in the United States and the highest case fatality of any foodborne pathogen [2]. V. vulnificus also causes serious skin/soft tissue infections. This can occur either through exposure of a preexisting wound to contaminated seawater, or through injury while handling contaminated seafood. Cutaneous infections can present as cellulitis or bullae, which can progress to necrotizing disease and secondary sepsis is left untreated.6

No epidemiological link was able to be established between this patient’s case and either seafood or exposure to seawater, although cases of V. vulnificus infections among patients without classical exposure risk has been documented.7 This case of V. vulnificus primary septicemia highlights the acuity of this presentation as well as the importance of including V. vulnificus in differential diagnosis of hosts with associated risk factors and/or epidemiological links. Blood culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Importantly, doxycycline in combination with a third-generation cephalosporin constitutes the standard regimen for antibiotic therapy – however, doxycycline is not usually considered a first-line antibiotic for management of patient with gram-negative bloodstream infections, so rapid and accurate identification of V. vulnificus in this setting is essential.

1. Kokashvili, T., et al., Occurrence and Diversity of Clinically Important Vibrio Species in the Aquatic Environment of Georgia. Front Public Health, 2015. 3: p. 232.

2. Baker-Austin, C., et al., Vibrio spp. infections. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2018. 4(1): p. 1-19.

3. Hughes, M.J., et al., Notes from the Field: Severe Vibrio vulnificus Infections During Heat Waves – Three Eastern U.S. States, July-August 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2024. 73(4): p. 84-85.

4. Jones, M.K. and J.D. Oliver, Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun, 2009. 77(5): p. 1723-33.

5. Bharathan, A., et al., Implication of environmental factors on the pathogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus: Insights into gene activation and disease outbreak. Microb Pathog, 2025. 204: p. 107591.

6. Coerdt, K.M. and A. Khachemoune, Vibrio vulnificus: Review of Mild to Life-threatening Skin Infections. Cutis, 2021. 107(2): p. E12-e17.

7. Candelli, M., et al., Vibrio vulnificus—A Review with a Special Focus on Sepsis. Microorganisms, 2025. 13(1): p. 128.

-Rene Bulnes, MD is an Infectious Diseases Clinician and current Medical Microbiology Fellow at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical enter in Dallas, TX.

-Andrew Clark, PhD, D(ABMM) is an Assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in the Department of Pathology, and Director of the Bacteriology Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. He completed a CPEP-accredited postdoctoral fellowship in Medical and Public Health Microbiology at National Institutes of Health, and is interested in the molecular mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance, susceptibility testing, and the evaluation of novel technology for the clinical microbiology laboratory.