A 78 year old woman was transferred from a nursing home to the Emergency Room because of delirium and worsening bilateral chronic foul-smelling hip wounds. Physical exam was notable for a fever of T103.2°F and purulence from the right hip wound.

Lab results included wbc 17.2K/mm3, hct 26%, platelets 694K/mm3, CRP 9.4 mg/dL, and ESR >130 mm/hr. A pelvic CT scan and X-rays of the hips and femurs showed signs of necrotizing infection, with soft tissue defects over both hips accompanied by subcutaneous fluid, inflammation, gas tracking deep to the femurs, and cortical irregularities of both greater trochanters.

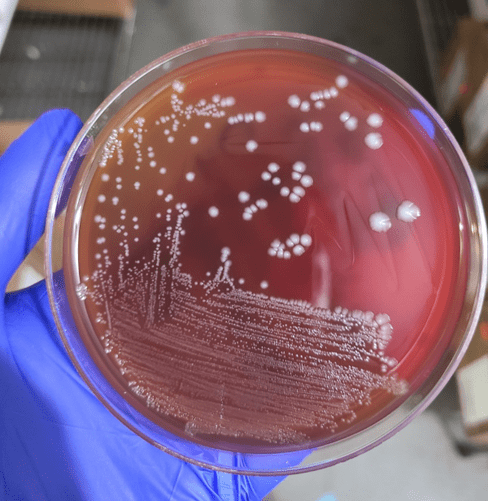

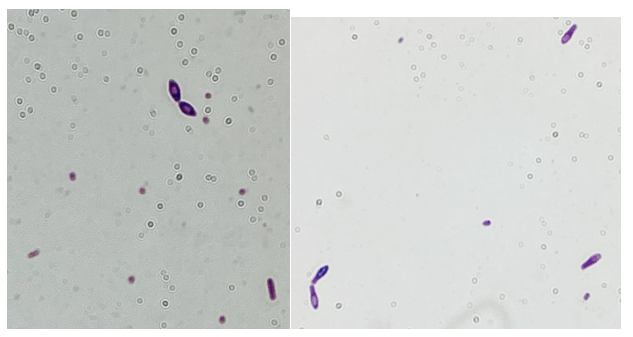

Gram-positive rods grew from the anaerobic bottles of two blood culture sets drawn on arrival at the hospital. Anaerobic blood agar plate growing colonies of gram-positive rods after 48 hours of anaerobic incubation are shown in Figure 1, and Gram stains of the same organism grown in cooked meat broth are shown in Figures 2A and 2B.

Gram-positive bacilli (GPB) were isolated from the blood. GPB in blood cultures are often brushed off as possible contaminants. However, in the setting of a possible necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) and the growth of GPB in anaerobic bottles only, concern for Clostridium spp. is reasonable. NSTI can be caused by a variety of different bacteria, but empiric treatment should reliably cover Clostridium species, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus, as they are the most commonly implicated pathogens. While C. perfringens is a common cause for gas gangrene, C. septicum frequently causes non-traumatic gas gangrene because of its aerotolerance.1

The GPB in this patient’s blood was identified by Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) as C. sporogenes/botulinum group I. While C. botulinum is a more familiar pathogen, both of these two closely related bacteria can produce botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT). In a comparative genomic study, C. botulinum Group I was found to possess genes for BoNT A, B, and/or F, while the C. sporogenes possessed BoNT B only.2 Detection of BoNT remains a challenge. Additionally, MALDI-ToF MS cannot distinguish between C. botulinum and C. sporogenes in most cases due to the similarity between these two species.

Since BoNT is considered a category A Biological agent, caution must still be taken when processing suspicious C. botulinum isolates in the laboratory during the identification. While the specimen collection and transport guidelines from American Society of Microbiology (ASM) described not attempting to culture the organism, the guidelines stated that clinical laboratories may still perform routine cultures that may contain Botulinum that potentially produces BoNT.

While it can be challenging to determine the presence of C. botulinum in wound cultures due to the gram feature similarities to skin flora gram positive rods, the laboratories should process the culture workup in biosafety level-2 (BSL-2) cabinet and avoid aerosol-generating procedures (e.g. catalase) to minimize the potential aerosolization of the toxin. The best practice would be an open communication between clinicians and the laboratory – for clinicians to notify the laboratory of potential BoNT cases/cultures when they send microbiology specimens. Post-analytical safety measures must be performed. So, what lesson did we learn here? While it is challenging to distinguish between C. botulinum and C. sporogenes in this case, a proper chain of actions (analytical and post-analytical measurements) should have been taken place to rule out/in BoNT-producing C. botulinum.

Susceptibility testing for anaerobes is not performed routinely and is only appropriately performed on isolates from sterile sources. Globally, rates of clindamycin resistance appear to be increasing among Clostridium spp. However, metronidazole and amoxicillin-clavulanate remain viable options for treatment of Clostridium spp.3-6

References

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1600673

- https://asm.org/ASM/media/Policy-and-Advocacy/LRN/Sentinel%20Files/Botulism-July2013.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7551954/

- Sárvári KP, Rácz NB, Burián K. Epidemiology and antibiotic susceptibility in anaerobic bacteraemia: a 15-year retrospective study in South-Eastern Hungary. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022 Jan;54(1):16-25. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1963469. Epub 2021 Sep 24.

- Ali S, Dennehy F, Donoghue O, McNicholas S. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of anaerobic bacteria at an Irish University Hospital over a ten-year period (2010-2020). Anaerobe. 2022 Feb;73:102497. Epub 2021 Dec 5.

- Di Bella S, Antonello RM, Sanson G, Maraolo AE, Giacobbe DR, Sepulcri C, Ambretti S, Aschbacher R, Bartolini L, Bernardo M, Bielli A, Busetti M, Carcione D, Camarlinghi G, Carretto E, Cassetti T, Chilleri C, De Rosa FG, Dodaro S, Gargiulo R, Greco F, Knezevich A, Intra J, Lupia T, Concialdi E, Bianco G, Luzzaro F, Mauri C, Morroni G, Mosca A, Pagani E, Parisio EM, Ucciferri C, Vismara C, Luzzati R, Principe L. Anaerobic bloodstream infections in Italy (ITANAEROBY): A 5-year retrospective nationwide survey. Anaerobe. 2022 Jun;75:102583. Epub 2022 May 11.

-Antoinette Acobo, PharmD, is 2nd year pharmacy resident specialized in infectious diseases in her 2nd year of residency. She performed several quality initiative and improvement projects, including antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) and cost/benefit analyses of rapid blood culture identification (BCID) multiplex panels.

-Phyu Thwe, Ph.D, D(ABMM), MLS(ASCP)CM is Associate Director of Infectious Disease Testing Laboratory at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY. She completed her medical and public health microbiology fellowship in University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, TX. Her interests includes appropriate test utilization, diagnostic stewardship, development of molecular infectious disease testing, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis.